In the increasingly competitive world of youth soccer, the ability to prepare athletes technically, tactically, and physically at a high level is growing in importance for both the club and athlete alike. Quite simply, clubs want to be able to attract the best players and players want to play for the best clubs. As result, specialization from a coaching perspective is becoming more common. Individuals with highly specific skills with regard to technical training, in-game management, nutrition, sports psychology, and performance are becoming more valuable as the margins for error in any one these components become smaller and smaller.

With athleticism such a large part of the game of soccer, and speed perhaps the most sought-after attribute, having a good performance coach can truly make all the difference. Share on XAs with many things in life, attention to the finest detail is often what separates elite from great and great from good. With athleticism being such a large part of the game of soccer, and speed being perhaps the most sought-after physical attribute, having a good performance coach can truly make all the difference. Most professional clubs have had full-time dedicated performance specialists for years. More recently, there has been a growing trend among youth organizations to provide professional-level physical preparation for their young soccer players as well.

The Elephant in the Room – Female ACL Injury Rates

The primary goal of the performance coach at the youth level should be to make sure athletes are prepared for the rigors of soccer. Health and vitality should supersede performance at the critical stages of early development. A comprehensive program in which a soccer player simultaneously develops strength, power, speed, and fitness will address both injury prevention and performance. General physical preparedness is far superior to sport-specific development among young athletes.

Video 1. It’s easy to get silly with plyometrics, so make sure the drills in your program look sharp and not wild. Single leg hops with crisp landings are better than chasing extreme heights or complexity.

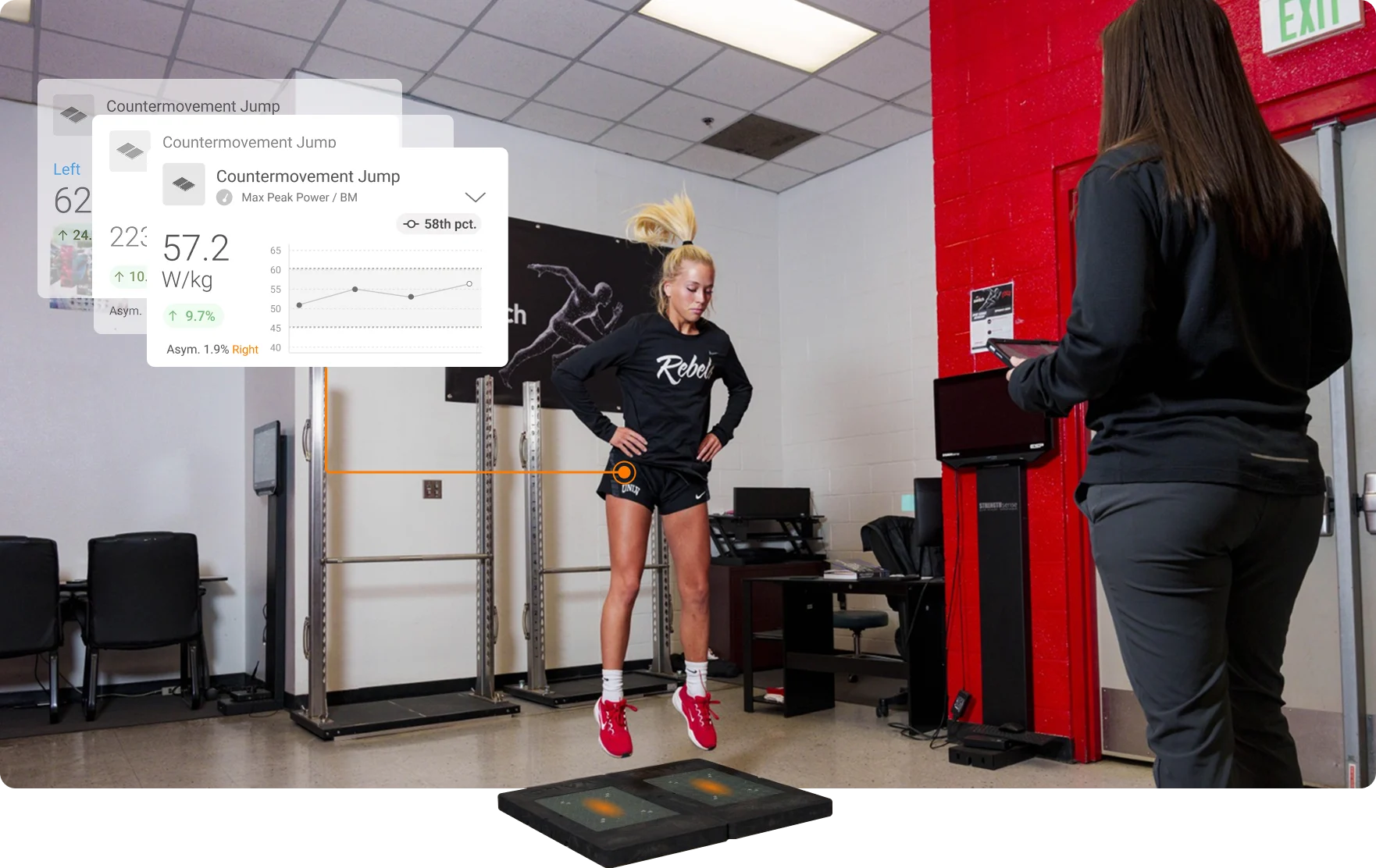

Collecting simple objective data points regarding performance provides insight that the process of physical development is on track. Data is also useful for revealing trends. Trends can be unique to an individual, possibly foreshadowing game-breaking efforts reflected in recent growth in performance indicators, or just the opposite, systemic fatigue or impending injury with sudden drops in indicators.

Trends can also be common among a population of athletes. For instance, the alarmingly high rate at which female soccer players experience ACL failures is one such trend. U.S. Youth Soccer has stated: “Numerous research studies that have been conducted over the past 10 years indicate that females are indeed more susceptible to ACL injuries; most studies report that females are 4-8 times more likely to tear this ligament.” In fact, many U.S. Women’s National Team members both past and present have suffered ACL tears, including recognizable names such as Alex Morgan, Megan Rapinoe, Brandi Chastain, and Shannon MacMillan, just to name a few.

The anterior cruciate ligament lies deep inside the front part of the knee behind the patella (knee cap) and connects the tibia (shin bone) to the femur (thigh bone). Its primary purpose is to provide stability to the knee by resisting excessive rotation and forward shift as the tibia relates to the femur. When the ACL is partially or completely torn as a result of excessive rotation of the tibia, stability around the knee is compromised.

Anatomically, women are at a disadvantage in comparison to men. Women have wider hips and a smaller intercondylar notch, which is the groove at the bottom of the femur where it meets the knee. This, in turn, can lead to inefficient movement patterns and biomechanics and leave the female athlete more susceptible to ACL injury. This predisposition is often exposed in more intricate sporting movements that involve landing, change of direction, lateral movement, or rotation. Incorporate physical contact as well, and you have a challenging environment for the female soccer player to safely navigate.

The best way to begin to combat the ACL epidemic in women soccer athletes is to get them strong. Share on XThe best way to begin to combat the ACL epidemic in women soccer athletes is to get them strong. Coordination/skill, rate of force, and the ability to decelerate are also necessary, but functional strengthening through a full range of motion in all planes of motion using conventional barbells, dumbbells, and kettlebells should be the foundation of a solid strength and performance program. Squatting, hinging, pressing, and pulling with mixed loads and velocities should be employed to develop both absolute and relative strength simultaneously.

Due to the energy demands of soccer, the ability to increase power while maintaining weight without adding excess bulk is very important. I personally use 1-5 rep maxes in the back squat, hex bar deadlift, and bench press as indicators of absolute strength, and chin-ups and skater squats (single leg squats) as indicators of relative strength. Optimizing both absolute and relative strength makes an athlete more resistant to fatigue.

This is important because most ACL injuries occur when the athlete begins to get tired. An American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine study monitoring vertical jump and drop jump performance concluded that high-intensity aerobic activity makes an athlete 45% more susceptible to an ACL injury. As an athlete fatigues, their ability to efficiently produce and absorb force dissipates and motor patterns break down.

While it is important to develop total body strength to maintain a well-rounded athlete, we should place primary emphasis on developing strength and stability through the legs and the core. The hips, glutes, hamstrings, lower back, and abdominals comprise the entirety of the core, which is the primary engine not just for a soccer player, but an athlete in general. Much of the stability around the knee builds on a strong foundation in the hips. Proper glute development and function, as well as sufficiently strong hamstrings, are necessary for a strong healthy knee.

Soccer athletes, both male and female alike, too often have significant muscle imbalances due to the quad-dominant nature of soccer and the lack of prerequisite strength of the hamstrings. Addressing this imbalance by strengthening the muscles of the posterior with squats, deadlifts, good mornings, glute-ham raises, and Nordics will not only create a safer environment for knee health, but also enhance performance. The glutes and the hamstrings are the most important muscles involved in sprinting. Bret Contreras specifies even further, suggesting that hamstrings are most important during the swing phase, whereas glutes are most important during the stance phase. Developing maximal force, rate of force, and speed of contraction for these two critical muscles is a must for a healthy, dynamic athlete.

Getting Started on a Path to Resilience with Strength

When beginning to strengthen an athlete, always be mindful that good strength development is first established on position. A strong position through a full range of motion in global movements such as a squat, hinge, press, or pull allows the athlete to move with load and velocity safely and efficiently later.

Video 2. Inchworms are great for athletes at any time, not just during the warm-up. Coaches need to think about remedial drills as basic strength, not just barbells and dumbbells.

Programming or, in some cases, reprogramming the nervous system or circuitry that controls muscular function is equally as important as developing the muscle itself in the female athlete. Combining and varying different types of muscular contractions early in development and strength-building cycles is excellent for promoting healthy strong positions in female soccer players.

“Controlling the stretch reflex is one of the most powerful assets an athlete possesses” –Cal Dietz.

Isometrics, or static holds, at various joint angles are great at developing strength at that specific position and providing a lot of neural feedback and a heightened sense of self-awareness. Fixed isometrics are also great because athletes can do them frequently without much muscular soreness or fatigue. Quasi-isometrics and eccentrics are also highly effective at developing high levels of strength in position. Quasi-isometrics are movements that are so slow they are nearly imperceptible. Quasi-isometrics can be done both eccentrically and concentrically through a full range or limited range of motion.

Eccentrics are specific to developing the stretch phase of a muscle and are critical in the deceleration process. The ability to effectively decelerate and absorb force is the essential first step in agility and change of direction, which so frequently occurs in soccer. Being incredibly strong will allow female soccer athletes to safely deal with the high forces generated from sprinting, leaping, and cutting.

Once sufficient levels of strength are demonstrated, athletes can dedicate more of their time and energy to doing more traditional speed, agility, and plyometric work. Ideally, I look for a 1.5x bodyweight squat, 10 full range of motion skater squats (single leg squats) with no knee valgus on each leg, and at least three good-quality chin-ups before really shifting my focus. It is important to note that these numbers are not absolutes and merely represent round estimates as to the ideal level of preparedness for more intensive training. Speedwork is really where all the strength and power development rightfully should manifest itself from a performance standpoint. Strength work may be the foundation on which power and speed are built, but how the athlete translates that to the field is what is most critical for a soccer player.

Strength work may be the foundation on which power and speed are built, but how the soccer player translates that to the field is what is most critical. Share on XTo that end, I always try to make sure I have a purpose for everything I have my athletes do. I’m constantly searching to create the biggest adaptation by utilizing the simplest means possible. In fact, it’s funny to look at my own evolution as a coach. When I first began nearly a decade ago, I used to constantly think about what exercise I could add or what elaborate progression I could use to take an athlete from point A to point B. Now it’s entirely the opposite—it’s more about what I can remove to simplify and make the entire development process more efficient.

Speed and Change of Direction Reserves – My Philosophy of Training

The value of speed, agility, and plyometric work is twofold. First, moving as fast as possible against little or no external resistance will increase the rate at which critical muscles such as the glutes, hamstrings, hips, and adductors are recruited. This is typically just viewed through a performance prism, but it is also largely beneficial in the reduction of ACL injuries because the same muscles are so important in the functional bracing of the knee. As quickly as an athlete can recruit a muscle to produce force, they can recruit the same muscle to absorb force.

Video 3. As youth athletes grow, landing skills must be introduced as they are now more at risk to ACL tears. Simple drills are great precursors for true plyometrics and are easy to implement in groups.

To specifically work on rate of recruitment and force absorption, I like to couple decelerations and landings from all different heights and angles with eccentric strengthening exercises. In sports such as soccer, where so much agility and change of direction are required, the ability to stop on a dime is arguably just as important as possessing breakaway speed.

In sports such as soccer, where so much agility and change of direction are required, the ability to stop on a dime is arguably as important as possessing breakaway speed. Share on XSecond, the technical development of speed, agility, and plyometrics will increase a female soccer player’s biomechanics in terms of positioning. As the athlete becomes more efficient in position when sprinting, leaping, or cutting, both performance and stability will improve. If an athlete is not strong enough to establish and maintain positions in static holds or under slower velocities as experienced against an external load, there is no chance they will be able to do so at full speed.

Optimal dosing for speed/agility and strength work would be 2-3 sessions per week of roughly 45 minutes in length, depending on whether in or out of season. The important thing is to make sure the sessions are as efficient as possible. The quicker and more effective the session, the quicker soccer players can get back to getting on the ball to develop their craft. When organizing training, I like to divide speed and agility work into three distinct parts: acceleration, max velocity, and agility. Each training session focuses on one theme, typically prior to strength work.

Acceleration

For acceleration work, I like drills that teach athletes to create a large amount of horizontal force rapidly. Postural drills done on the wall provide a great initial proprioceptive learning tool, allowing an athlete to feel the appropriate body lean while simultaneously maintaining correct limb orientation to effectively “push.” Lightly resisted accelerations and horizontal med ball throws that finish both with and without an acceleration are great at teaching the sensation of projecting the hips horizontally.

From a cueing perspective, I stress “strong” over “fast.” In my experience working with many young athletes, often in large group settings, utilizing “strong” to describe the first few steps during acceleration has proven to be the most effective at reaching the broadest audience.

Max Velocity

For max velocity work, basic technical drills that integrate posture, balance, and rhythm of ground contact such as ankling, prime times, derivations of A skips/A runs, skips for height/distance, and wicket runs are excellent. Fly-ins at 10-30 yards and float-hit-float runs are fantastic as well, because they require an athlete to effectively accelerate before reaching top speed and develop continuity between drive phase and max velocity. As an athlete’s top end speed improves, so does their ability to accelerate, which is precisely why it cannot be overlooked in the development of soccer athletes despite soccer primarily being acceleration-oriented. Plyometric exercises that produce vertical forces—such as pogo jumps, depth jumps, tuck jumps, and pike jumps—are great at developing the fast stretch shortening cycle necessary for ground contacts at max velocity.

As an athlete’s top end speed improves, so does their ability to accelerate, which is precisely why it cannot be overlooked in the development of soccer athletes. Share on XAgility

To develop change of direction and agility, I prefer a combination of eccentric strength, decelerations/landings, and multidirectional plyometrics, as opposed to traditional choreographed cone and ladder drills. With the amount that female soccer athletes train and compete, they get enough sport-specific agility by merely playing. Therefore, it is unnecessary to administer any extraneous cutting, turning, and shuttle drills during their preparedness sessions with me. Employing a mixture of eccentrics, decelerations/landings, and plyos develops agilities underlying the mechanism of force absorption, lowering of center of mass, and proper ground contacts in relationship to the athlete’s center of mass in all planes of motion.

With legitimately unlimited degrees of freedom regarding change of direction scenarios within the game of soccer, having a female soccer athlete “learn to read” in training so she can “read to learn” while competing is of far greater value. The addition of reaction components to these various building blocks incorporates a layer of cognitive function and perception to the drill, making it slightly more sport-specific. Choreographed change of direction drills, such as the 5-10-5, 3-cone drill, and long shuttle, provide value primarily as feedback mechanisms to ensure development is on track. Choreographed change of direction drills are more for demonstration than development.

Warm-Up

Always begin with a good 5- to 10-minute dynamic warm-up. An effective warm-up should raise core temperature; elevate heart rate; activate and mobilize muscles of the glutes, hips, and core; and finally, excite the nervous system. I have found a nice mixture with subtle contrasts in resistance, time under tension, and intensity with glute/hip bands in combination with bodyweight mobility such as multiplanar lunges, single leg RDLs, Frankensteins, and a variety of crawls highly effective at preparing the body for more explosive movements. To fire up the nervous system, quick footwork, hops, jumps, and accelerations are simple and effective.

Video 4. Having athletes learn strength movements, even light ones, on the field helps them connect the dots. You don’t have to work seperate the gym and the field, but know when to employ real overload.

Active Restoration

After training and competing, it is always in an athlete’s best interest to gradually cool down as opposed to just abruptly stopping, but don’t expect a magical recovery. A 5- to 10-minute conventional cool-down is the first step in preparing mentally for the next session or competition by restoring baseline wellness, range of motion, and mobility, and addressing any sore or injured muscles. Mobilizing the hips and shoulders with simple abduction/adduction, extension/flexion, and external and internal rotations before some light static stretching or positioning and gentle foam rolling or lacrosse ball smashing can be very helpful in restoring an athlete to resting state.

Video 5. Activation for elite athletes may be overzealous, but developmental athletes benefit from the teaching and the resistance. Don’t forget that eventually you may need to move on from light resitance and progress to more demanding exercises.

An example training session emphasizing acceleration work and eccentric strengthening would look something like this:

Warm-Up

- Lateral Glute/Hip Band Monster Walk 1×10 steps r/l (band around ankles)

- Walking Lunge + T Spine Rotation 1×10 yds

- Glute/Hip Bridge + External Rotation 1×10 (band around knees)

- Alternating Single RDL 1×10 yds

- Kneeling Hydrant Circles (1×5 slow external, 1×5 slow internal r/l)

- Wideouts (CNS) 1×15-20 s

Acceleration

- Falling Boom + 5-Step Wall Acceleration x4 (2 r/l) (posture/position)

- Band Resisted Partner Accel from Kneeling 1/2 Start 3×20 yds

- Kneeling Squat Jump + Horizontal Med Ball Throw for Distance 2×3

- Timed 20-yd Acceleration from 2-Point Stance x3

Power

- 12” Depth Jump to Hurdle 2×3

Strength

- Eccentric Back Squat (5:0:0) 70%x3x3

- Eccentric + Isometric RDL (5:2:0) 2×5

- Eccentric Chin-Up (5:0:0) 2×4-6

- DB Lateral Lunge (light) 2×10 r/l

Stability/Mobility

- Dead Bug (contralateral) 1×16

- Side Plank + Abduction 1×12 r/l

- Single Arm Plank 1×20-30s (strict position)

- 90/90 Internal Rotation Hip Switches 1×16

- Backward Bear Crawl + Glute/Hip Band Around Knees 1×10 yds slow

- Low Squat + Slow Internal Hip Rotations 1×45-60 s

Mastery Disguised as Polishing the Basics

At the end of the day, developing high levels of strength and becoming skillful at sprinting, leaping, and cutting are the best ways to fight the growing ACL epidemic among female soccer players. Simple, time-tested means such as squats, deadlifts, and presses done at an extraordinarily high level will prepare girls properly for the forces they will face in training and competition. Be wary of programs that seek to build stability through instability and commonly throw about such buzzwords as “sport specific.” Stick to the basics, be demanding, and get your girls strong!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF