Bri Brown is currently the S&C coach for the University of Pittsburgh’s women’s basketball team. Prior to joining the Panthers, she served as the Director of High Performance for the Racing Louisville FC of the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL). While in Louisville, Brown was responsible for implementing and developing all aspects of individual player and team strength, conditioning, mobility, readiness, and recovery sessions, and she oversaw all aspects of team nutrition.

Brown spent three seasons as the Director of Women’s Soccer and Basketball Sports Performance at the University of Houston before making the move to professional soccer in 2021. While a member of the Cougars staff, she was responsible for implementing all aspects of strength, conditioning, and recovery for the women’s basketball and soccer teams. She also oversaw all aspects of professional development and education for the basketball sports performance staff.

Freelap USA: Every institution has unique systems and processes in place—what have been some of the biggest adjustments you’ve had to make in coming to the University of Pittsburgh from Racing Louisville FC and the University of Houston? What advice can you offer young coaches about successfully transitioning into a new position?

Bri Brown: One of the biggest adjustments I’ve had to make in a positive way is having so many more resources and people on staff to collaborate with. Here at the University of Pittsburgh, we have a sports dietician fellow, athletic trainer, sports science assistant, physical therapy fellow, and me who are all only dedicated to women’s basketball.

I had to wear multiple hats in my previous roles, overseeing sports science, nutrition, return to play, and strength and conditioning. I sometimes felt I didn’t have enough time to do everything or had to sacrifice doing more in one area to make sure the whole picture was being taken of. But because we have a dedicated performance team, we all have more freedom to really hone our craft and operate at high levels across the board.

One piece of advice I can offer someone when transitioning into a new role is to step back and evaluate the systems that are in place: not everything needs to be fixed, says @briannebrown10. Share on XOne of the first pieces of advice that I can offer someone when transitioning into a new role is to step back and evaluate the systems that have been put in place: not everything is “wrong” or “bad” and needs to be fixed. Address change in what you deem your low-hanging fruit and then continue to find ways to add value.

The second piece of advice is to address the needs of the athletes and the program that you have in front of you. What worked at your last stop might not be what you need or what is right for your current team, organization, or program in your new position.

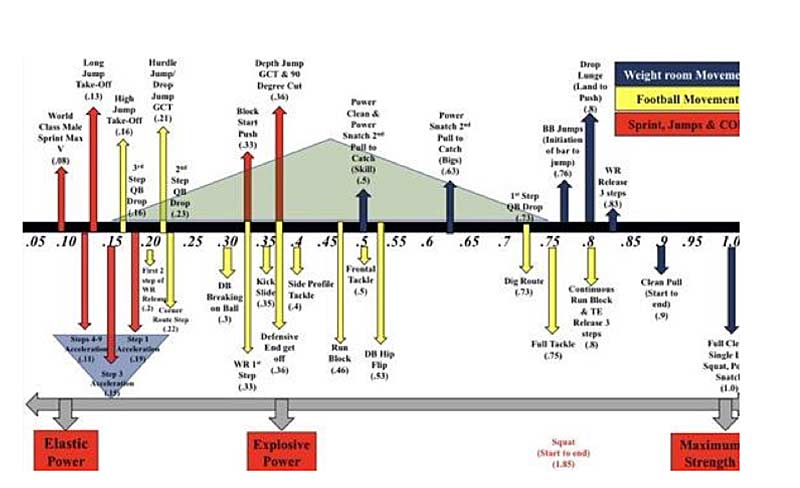

Freelap USA: What are some of the most effective strategies for developing explosive and powerful basketball players that you have learned during your journey as a coach? What are some exercises and modalities you’re introducing with your athletes at Pitt that are new or unfamiliar to them?

Bri Brown: There are an infinite number of ways to go about making athletes—and not just basketball players—more explosive and powerful. The most effective way to aim to improve those characteristics is through consistent, detailed, and well-progressed training. Basketball players, and in all reality, most college athletes, tend to arrive undertrained and underdeveloped. Consistent training has been the most effective development factor when improving explosiveness and power.

I’ve been very fortunate to be heavily influenced in my coaching philosophies and principles by mentors such as Richard Borden, Dave Scholz, and Alan Bishop. I’m a big believer in ground-based, full-range-of-motion training, which we’ve incorporated into our training here at Pitt.

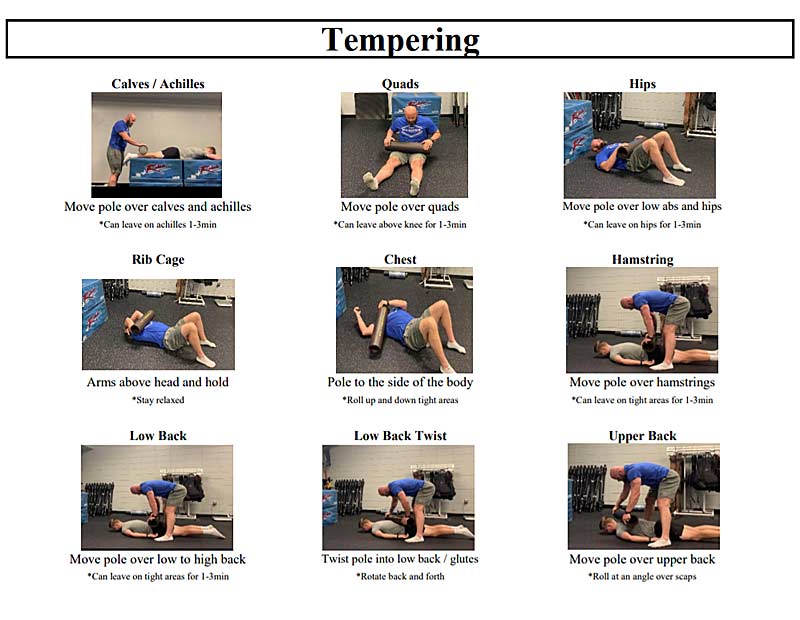

Some progressions have been different from what the players were used to. Still, at the end of the day, we’ve really put an emphasis on hammering home the basics and being competent and efficient in those movement patterns at a really high level. We’ve also introduced parts of the Functional Range Conditioning system to start addressing individual joint and mobility needs for each athlete.

Freelap USA: What were some of the highlights of the inaugural season with Racing Louisville FC? What are some lessons you have learned from working with international, professional athletes in a brand-new franchise that you can take with you back to the collegiate level?

Bri Brown: Beating Bayern Munich in PKs to win the Women’s Cup was a huge highlight of the season. Being able to experience the atmosphere for the first home game in the club’s history in one of the best NWSL stadiums was also incredible. But working with a top-class technical staff and some of the most elite women’s soccer players in the entire world on a daily basis was the best part of working at Racing Louisville this past year.

Whether a college-level or pro athlete, there’s still a need for education and the application of nutrition, recovery, and training principles to help maximize performance, says @briannebrown10. Share on XOne of the biggest takeaways I found at the professional level is that the continual education of your athletes is still important across the board. Our jobs are ultimately to help maximize performance. Whether you’re dealing with a freshman basketball player or a former World Cup champion, there is still a need to provide education and the application of nutrition, recovery, and training principles to help maximize performance.

Freelap USA: What are some unexpected commonalities in performance training for soccer and basketball, and what are some essential differences between the two that you may not have anticipated earlier in your career? How has working with different sports helped make you more well-rounded as a performance professional?

Bri Brown: When I’m working with a team, I don’t differentiate my training based on the sport; I base my training progressions and desired training adaptations on the needs analysis of the individual players and/or team as a whole. By going about performance training based on a needs analysis, you’ll quickly find that 90% of the training you do won’t differ from sport to sport.

One of the most important differences I’ve learned has been the increased need for overhead development in basketball players. Each position in basketball requires overhead and upper body development, while for soccer, additional overhead training might only be needed for certain positions.

Working with a multitude of sports has helped fine-tune my coaching eye. I’ve seen thousands of reps across multiple sports, which has made me very comfortable in coaching settings. It has also helped me develop my coaching voice and better understand different sports cultures, and it has taught me how to connect with different personalities and backgrounds.

Ultimately, being exposed to a variety of sports has shown me how important it is to have training principles. What makes you well-rounded is the ability to implement those training principles no matter the sport you’re working with. I would encourage all young coaches to get on the floor and coach with as many teams and student-athletes as humanly possible.

Ultimately, being exposed to a variety of sports has shown me how important it is to have training principles, says @briannebrown10. Share on XFreelap USA: How have you been able to apply your knowledge of nutrition and recovery with your athletes? What are some of the most effective ways you’ve found to work toward making a positive impact on your athletes’ eating habits and helping them fuel for performance?

Bri Brown: I’ve been very fortunate thus far in my career that I’ve been able to directly oversee the nutrition and recovery for the teams I’ve worked with. In terms of nutrition, I’ve used my knowledge to dictate travel menus, game menus, training table menus, snacks, locker room or fueling station food selections, and supplementation protocols for my athletes. Nutrition is the “X-Factor” and has huge implications on training and recovery. Because of this, my number one priority is always finding ways to provide quality nutrition to the athletes and make it as accessible as humanly possible.

As coaches, we are ultimately teachers; so, consistent education, just like consistent training, has been one of the most effective ways I’ve seen to make positive impacts and get buy-in. I always make sure I’m present at team meals, snacks, the training table, and in the locker room. Those settings invite informal conversations to continually provide added education and for your athletes to see that you care about how they take care of their bodies.

It’s not always easy, it’s rarely glamorous, and it requires a huge commitment not just from your student-athletes but the coaching staff, support staff, and administration.

Lead photo by Andrew Bershaw/Icon Sportswire.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF