Many strength coaches stress performing a triple extension during dynamic barbell movements such as cleans and snatches. After all, if the triple extension is good enough for powerful Olympic-style weightlifters, it must be good for any athlete who wants to run faster, jump higher, throw farther and, well, do just about everything better. Not quite.

I’m here to tell you that the triple extension is not what elite weightlifters are doing, and it’s not what the coaches of other athletes should be teaching. Further, triple extension exercises such as pulls adversely affect the technique of the full movements and do not produce as much power. As for hang power cleans, I’m not a fan, as those who’ve read my work already know. So, what is a triple extension?

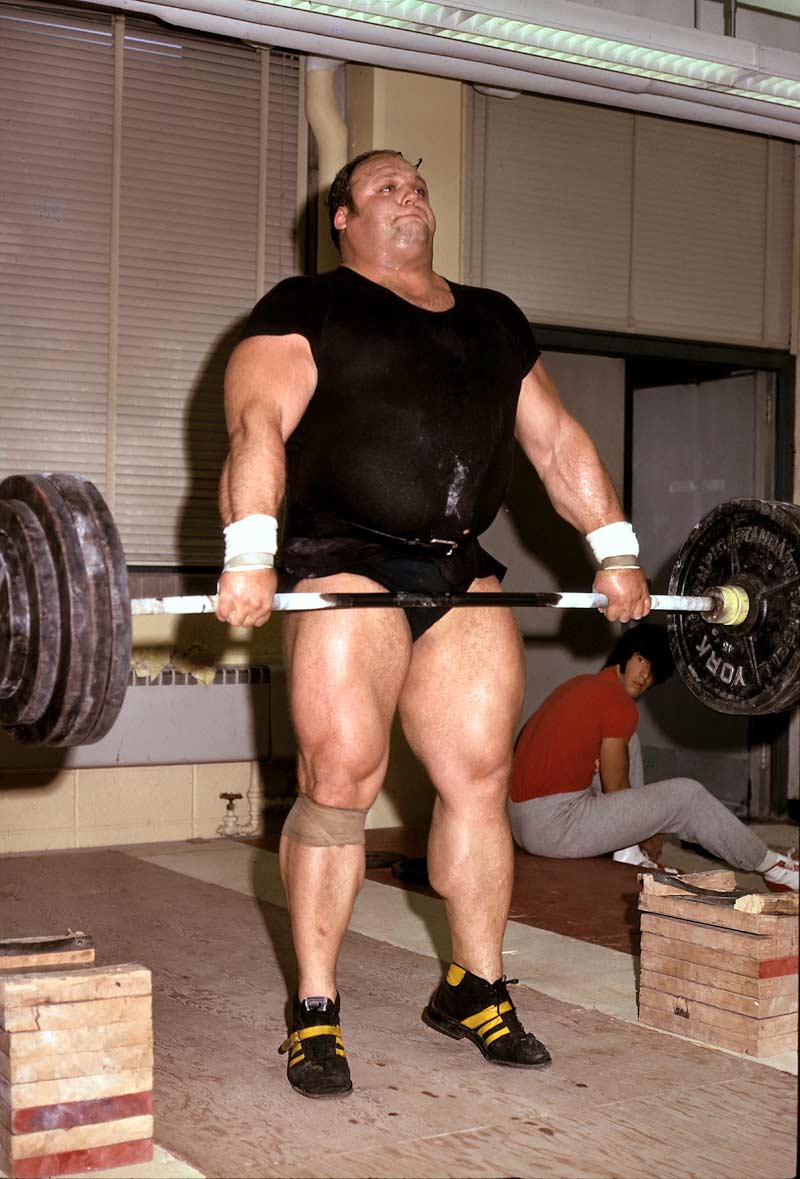

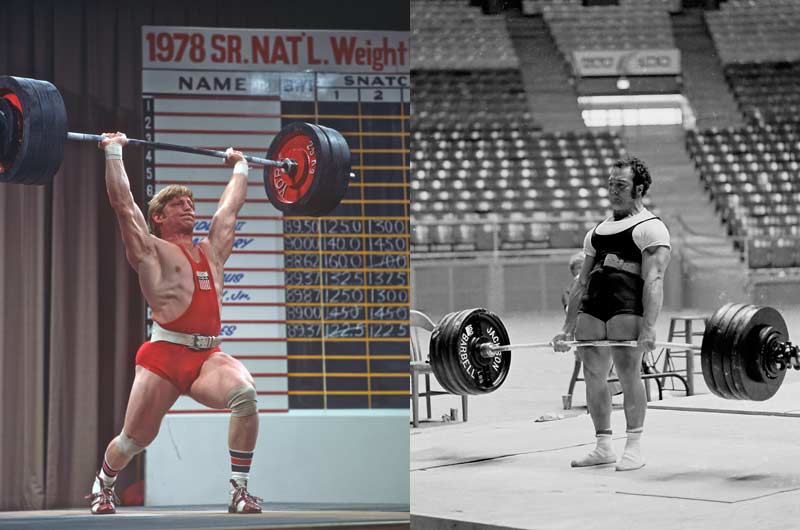

The triple extension is often defined as “achieving full extension of the ankles, legs, and hips to produce maximum power.” Frequently accompanying such a definition is a photo of a weightlifter rising on their toes, fully extended with their shoulders shrugged. Sometimes these photos show the lifter with their feet several inches off the floor, supposedly confirming the belief that weightlifting is simply “jumping with weights.”

Another aspect of triple extension mythology is the belief that the only purpose of lifting the barbell from the floor is to get it into position to finish the lift. Thus, it would make sense to ignore the first pull altogether and concentrate on cleans, snatches, and pulls from the mid-thigh. Let’s break down all this nonsense, starting with power.

Power Is Power

One familiar equation used to represent power in weight training is force x velocity x distance/time. Another is force x velocity. However you define it, the bottom line is that you can have more power or less power, but you can’t have explosive power or non-explosive power. Power is power. With that understanding, consider that the maximum power production for snatches and cleans is not produced at the top of the pull.

If you watch modern elite weightlifters, especially the Chinese women, they go up on the balls of their feet as the bar passes knee level. This approach is in contrast to the proponents of triple extension, who recommend staying flat-footed until the legs have fully straightened after the bar passes the knees. Why should we care?

When the legs are straight, neither the gastrocnemius calf muscle nor the smaller soleus calf muscle can contribute much to the bar’s vertical movement. Stand up, lock your knees, and try to jump—not much happens as far as the calves contributing to force production. Further, this technique causes the barbell to drift away from the center of mass.

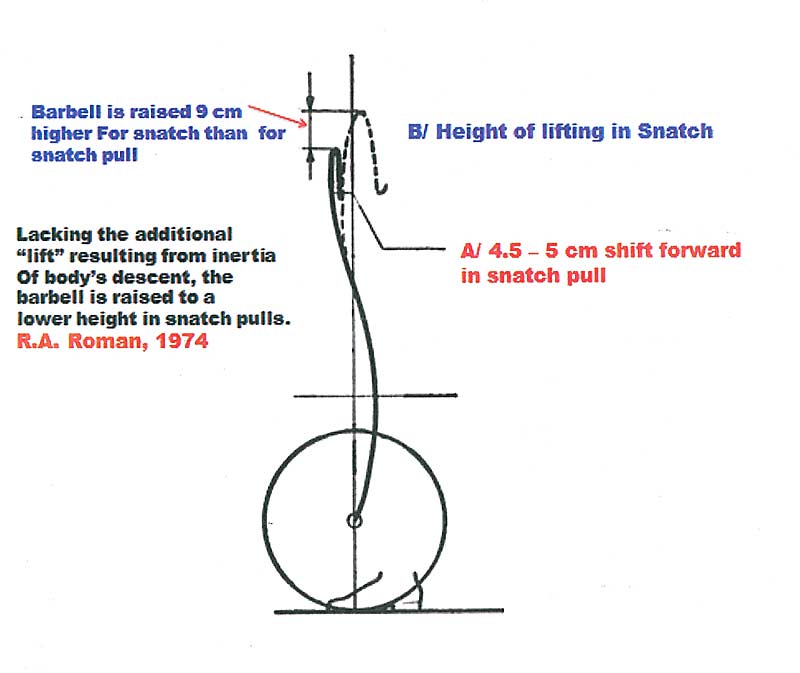

Let’s try another experiment. Grasp a stick and stand sideways, next to a mirror, legs straight. Place the stick on your mid-thighs. Look at the end of the stick, and then come up on your toes. You’ll see the bar move forward. As such, triple extension forces the athlete to use a different bar path than the full lift. Elite performance requires consistent technique. Why perform exercises that have a different movement pattern than the primary lift you want to improve? It would be like an NFL quarterback practicing with a fully inflated football in practice and then throwing a deflated one in a game!

#Tripleextension forces a different bar path than the full lift. Why perform a different movement pattern than the primary lift you want to improve? Share on XThere is an argument that using the calves early creates a dampening effect, reducing the force produced by the quads. It’s not true. The soleus assists with knee and hip extension (pulling the shin backward) and contraction of the gastrocnemius enables the quads to more effectively transfer additional force into the floor. These actions, along with the contributions of the elastic properties of the plantar fascia that is activated when the heels raise, combine to maximize power production well before full extension.

Lifters don't jump upward with a barbell during a snatch or clean; they contract the flexion muscles and jump down. Share on XSome coaches note that in watching elite lifters, their feet leave the floor, giving evidence that the pull is a jump—again promoting the idea that lifters are jumping upward with a barbell. No, they are not. At this point in the lift, these athletes are actually contracting the flexion muscles and “jumping down.”

If you look at sequenced photos of lifters performing a snatch or clean and use their torso as a reference point, you’ll see that although their feet may leave the ground, their torso descends. Thus, it’s not that a lifter pulls the barbell to a specific height and then lets gravity do the rest; the athlete actively moves under the bar before it achieves maximum height.

During the initial pulling portion of a clean or snatch, especially when using heavy weights with quality barbells, the ends of the barbell are lower than the center. As the lifter moves under the bar, the ends of the barbell are higher than the center. This action occurs because the lifter is pulling their body under the bar, resulting in an upward force on the barbell. With a pull exercise, whether it’s performed from the floor or the blocks, this whipping action does not occur.

A Brief History Lesson

This knowledge about lifting technique is not a sudden revelation. In a 1974 Russian sports science textbook, translated by sports scientist Bud Charniga, researchers analyzed the speed at which weightlifting superstar David Rigert moved his body. They calculated that during the non-support phase (when the feet don’t apply force into the floor), gravity could influence a free-falling object (in this case, Rigert) to drop 21 centimeters (8.2 inches) in 0.2 seconds. In fact, he dropped 59 centimeters (23 inches) in this amount of time! How is this possible?

Charniga explained that Rigert defied gravity because he used the barbell to pull himself down and flexed the hips, knees, and ankles—along with relaxing the extensor muscles used to lift the barbell during the initial pull off the floor. For these reasons, Charniga emphasized in his teachings that no jumping occurs in weightlifting—it’s the opposite of jumping.

As for hang power cleans, the effects can be even worse because the barbell’s initial movement is often diagonal, not vertical. This is especially true with the way many coaches teach the hang power clean.

In an attempt to have their athletes use their lower back muscles to produce force, many coaches teach athletes to start the hang power clean by extending their shoulders well in front of the bar. Besides not effectively using the power of the quadriceps, this starting position places high compressive forces on the spine. By having the shoulders so far in front of the body’s center of mass (which is about in the middle of the foot), the bar’s initial movement primarily is diagonal, not vertical.

After launching the bar off the thighs with this hip thrust, the lifter has to pull the bar backward (in a looping motion) that further increases the stress on the spine. The torture isn’t over, as now the athlete must receive the bar and stop suddenly rather than absorbing and redirecting the force as would occur in a full clean.

Triple Extension and Partial Lifts

Finally, there’s the idea that you can break apart the classical weightlifting exercises into their component parts. As such, we could duplicate a clean and jerk by combining exercises like a deadlift, hang clean, front squat, military press, and lunge. Sure—and the sky is blue because it reflects the ocean. Except for the hang clean, these movements are performed relatively slowly and don’t use the elastic properties of the connective tissues.

The strength developed with slow movements won't necessarily enable athletes to display their strength quickly. Share on XWe can trace this problem down to the cellular level as it involves the sarcomere, the primary contractile element of the muscle. With a focus on relatively slow, partial-range exercises, we create a different training effect on the sarcomeres than we would if we focused on dynamic, large amplitude movements such as a clean or a snatch. Although this discussion deserves an article by itself, you need to understand that the strength developed with slow movements will not necessarily enable athletes to display their strength quickly.

Another troublesome aspect of this blind devotion to triple extension is the suggestion that coaches are focusing on just producing force. Athletic fitness involves more than the ability to produce force; athletes also must absorb, store, and redirect force.

Athletic fitness involves more than the ability to produce force; athletes also must absorb, store, and redirect force. Share on XWhen we see an athlete make a sudden change of direction in competition and injure their ACL or ankle, we hear comments from sports coaches and strength coaches like, “Such is the nature of sports.” Or, with female athletes, these injuries are falsely attributed to their inferior anatomy or hormone fluctuations that make them more fragile in the first place. How else could they explain why the majority of ACL and ankle injuries are non-contact?

Athletes can achieve physical superiority by ignoring the functional training hype about the #tripleextension and doing Olympic lifts as intended. Share on XIn their effort to bring attention to their programs (or ignorance), many coaches have been giving out bad advice about how to perform dynamic exercises. Do the Olympic lifts the way they were intended, ignore the functional training hype about the triple extension, and watch your athletes achieve physical superiority.

Header photo by Viviana Podhaiski.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Charniga, Andrew, Jr., “The Ankle and the Asian Pull.” European Weightlifting Federation Scientific Magazine. No 12: January-April 2017.

Anderson, Frank C., and Pandy, Marcus G., “Storage and Utilization of Elastic Strain Energy During Jumping.” Journal of Biomechanics.

Van Ingen Schenau, G.J., “From Rotation to Translation: Constraints on Multi–Joint Movements and the Unique Action of Bi-Articular Muscles.” Human Movement Science.

Roman, Robert A., “The Training of the Weightlifter in the Biathlon,” Moscow, FIS, 1974. Translation by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

Formicola, Donato, Ph.D., “The Biomechanics of the Sacromere, The Origin of Muscular Force: Part Three.” European Weightlifting Federation Scientific Magazine.”

Lyons, Todd, Dynamic Fitness Equipment, Personal Communication, March 2019.

Thank you for the article.

If we define triple extension as ankles, knees and hips extended, Chinese weightlifters or any other good ones I have seen do triple extend. The question is whether during the quick transition phase (less than 300 milliseconds) you have different styles: heels flat or heels elevated. It is well documented and known that these 2 styles exist, but it does not change the fact that triple extension is real in the Olympic Lift. I would love to see a good Olympic lifter who does not have triple extension (ankles, knees or hips) in the snatch or clean.SEE Pictures here: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10156855971722626&set=p.10156855971722626&type=3&theater

Victor, thanks for the response. No, these elite lifters do not actively triple extend! The trainers who are promoting triple extension are saying that the top of the pull is where maximum power is occurring, and thus promote non-sense ideas such as only performing hang power cleans. The fact is, with elite lifters (especially the women from China), at this top position the muscles that extend the body are relaxing and the muscle involved in flexion are contracting. Waiting until the body is fully extended is too late, and you often see these lifters having the bar crash on them when they catch it (in addition to being very slow). The heels flat style is often accompanied by extending the shoulders in front of the bar for a long period, placing prolonged and excessive stress on the lumbar spine.

This is a great article, and you are right that elite lifters don’t actively triple extend. I think the confusion comes with the fact that triple extension occurs as a consequence of the lift i.e. it naturally happens at the end of the pull. I think this may be what Victor was referring to.

With regards to the last section though, Chinese lifters perform very heavy deadlifts (and squats) every week, even though they are performed at speeds well below those that occur in the competition lifts

Hey Nathan,

Can you elaborate the Chinese not actively fully extending? From what I’ve heard from Perfect Lift CN and other coaches, they teach full extension. I have noticed though that they focus mostly on timing the extension, and full hip and knee extension. They rarely talk about the ankle extension.

Kind regards

Hi Noel

My original comment was not very well written which may have caused some confusion. I should not have said they don’t fully extend. I should have said they don’t emphasise ankle extension (like you stated).

I have been with the Chinese WL team for just under 2 years now, so much of what I know often gets lost in translation, but as far as I am aware, not every coach will emphasise ankle extension. The Coach I work with told me though our “translator” (Chinese doctor who speaks English) that they emphasise hip extension and pulling the bar, so that ankle extension occurs as a consequence of this.

Have a look at Lu Xiaojun, his heels hardly leave the floor

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=glIRcIurOA8

However, some coaches may emphasise ankle extension. China is so big and has so many weightlifting schools, so that every coach will coach slightly differently. There isn’t a “Chinese Weightlifting Level 1” coaching manual that every coach follows.

Nathan

Hey I read the blog on triple extension and definitely agree it doesn’t make a lot of sense with the Olympic lifts. What’s your take on it for a barbell hip thrust I find that is more effective for patients to feel it in their glutes. Ik American barbell hip thrust is inferior for glute activation compared to conventional and that is likely due to the ppt probably and erectors kicking in. Wondering if you had any knowledge or literature on that? Thanks!

Thank you for this article!

Thought provoking article coach.

I would just like to clarify that the Chinese do teach full extension, albeit followed by a rapid relaxation and reversal of the movement. I think the main difference is that they don’t believe in ankle extension but rather full knee and hip extension.

Thank you for the comment. Look at the photos of Chinese female lifters with the bar just above the knees (such as with the second photo of Nicole in this article). They are performing ankle extension with the knees bent. Waiting until the end of a lift to perform ankle extension is a poor use of these muscle groups.

Hi Kim

Myself and some of my colleagues (and perhaps some of the others who have commented?) are struggling to understand and clarify some of your comments:

What do you mean by triple extension, and what do you mean it doesn’t occur? Because at the end of the 2nd pull, if the hips knees and ankles are extended, isn’t that triple extension? (perhaps this is what others who have commented are referring to?)

As you mentioned, during the transition phase (bar just above the knees) some lifters will have their heels off the ground, but don’t they still finish in triple extension.

Hi Kim,

Great article and explanation. However, I disagree that there is a myth of triple extension. In all sports, especially power based sports, such Olympic weightlifting, sprinting, throwing, etc.-triple extension is very much real and an efficient aspect of the movement.

I think the definition of triple extension is valid but may get into the weeds of semantics. Just because there isn’t always “FULL” extension or lockout of all 3 joints, doesn’t mean these athletes aren’t into triple extension. A joint is never “neutral”-a joint is either in flexion or extension.