Joey Bergles is the Director of Strength & Conditioning at JJ Pearce High School in Richardson, Texas. In addition to his coaching responsibilities at the high school, he oversees the S&C programs at the two junior highs that feed into JJ Pearce High School and works with third through sixth graders at elementary schools within the district. Prior to his current position, he worked in the collegiate setting, with stops ranging from the NAIA to Division 1 levels. Joey can be found on social media at @joeybergles (Twitter/Instagram/TikTok). He holds the following certifications and/or has attended the following courses: FRCms, FRA, Kinstretch, FR Lower Limb (Non-Therapist), Metabolic Analytics, Poliquin Internship Hours, DNS A, Art of Coaching Apprenticeship, CSCS.

Freelap USA: You’ve presented on how critical it is to design activities that have a high level of engagement when working with athletes who are in their early teens—what’s your process for choosing or developing those exercises that promote genuine engagement and how do you determine what is and isn’t working?

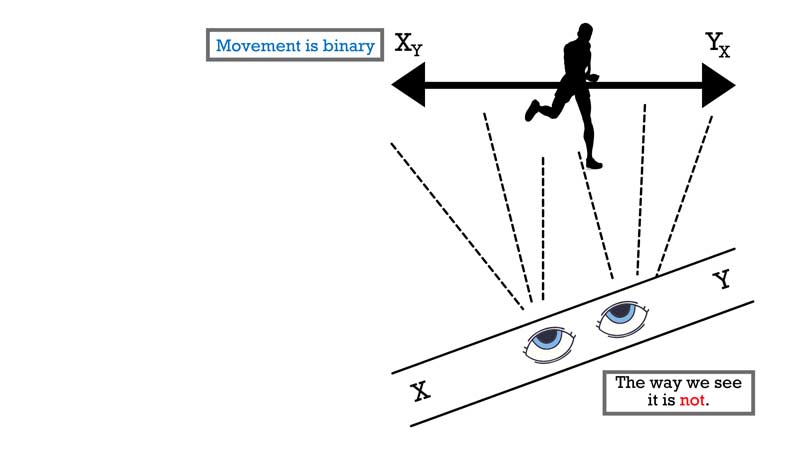

Joey Bergles: First, I need to have an idea of how many kids I’m working with, what ages they are, have I worked with them before—those kinds of questions. One of the biggest keys with high school and junior high school kids is how everything is structured, even just in terms of sightlines. When you’re trying to do different activities in a big open space and there are no dividers, that’s where attention gets lost.

That’s one of the biggest issues I’ve seen, and sometimes I have to decide if we’re going to use dividers or go into a hallway, because there may be five or six coaching points I want to make and there will be distracted people in the back with wandering eyes. On the other hand, in a smaller, confined area, all they can do is focus on me.

I’m very lucky with the facility that I have—we have a weight room and then an indoor training area next to our weight room, and our weight room has dividers that let us section it off into quarters. That was one of the keys that helped me in my junior high program this past summer—okay, we’re going to go 20, 25, maybe 30 minutes between the weight room and the four sections and the turf room, and then I’m going to structure my entire workout around that constraint. There may be other stuff I want to do, but if I can’t figure out how to do it within that specific setting, then I’m not going to do it or I’m going to figure something else out.

I’ll be honest, that was probably THE biggest thing, regardless of the X’s and O’s, because if you have smaller groups, then you have to rotate, and it takes more time to rotate. Realistically, in an hour session, we would have four stations—you’re talking about 12-13 minutes with each group. So, when you only have 12-13 minutes, you don’t have a lot of time to do a lot of stuff. And, if we’re doing stuff for seven or eight weeks, that’s where, when we’re doing progressions, you really see things flow together. So, it’s probably not going to be perfect on week 1, but by week 5 or 6, we’ll be working these progressions, and we’ll keep getting better.

If I keep the focus high and the engagement high, it’s amazing what can be accomplished. It’s almost like cheating, says @joeybergles. Share on XIf I keep the focus high and the engagement high, it’s amazing what can be accomplished. It’s almost like cheating. Regardless of level—professional or high school or whatever—when people are not focused or not paying attention or not very engaged, then everyone’s like well, we haven’t made very much progress in the past seven or eight weeks. But then is it the fault of the program or the people doing the program?

We’re not going to get 100 reps where I just walk around and coach everybody. When you have a large number of individuals and a relatively short amount of time, you have to be as efficient as possible. When you get individuals coaching each other, you’re going to get better execution out of everyone because I can’t coach 30 people at one time. If I can have partners where one person is in charge of another person, they’re coaching the things I’ve shown them they need to see: this, this, and this. Nothing super-hard, but they know what they’re looking for. Now that they’re actually good at coaching it, when the individual they’re coaching gets out of position or does something wrong, they’ll give feedback to make corrections on the subsequent reps so we can make quicker progress through the entire program.

People can say they’re going to have a 2.5-hour practice and the engagement level is going to be extremely high the entire time, day after day.… I’ve worked from high school to Division 1 in numerous sports; it is so hard mentally to be engaged and focused for that amount of time. I know for myself that I can’t be engaged for three hours. Even if it’s something strength and conditioning-related, if I’m reading a book or article, I can’t do that. So, do you really think 12-, 13-, 16-, 20-year-old kids will be able to do it? I’ll be honest, I think that’s a stretch.

We’ll make more progress with shorter rotations where the engagement is high. Athletes get so much better when they’re getting the feedback. People, in general, recognize what you praise. A lot of times, I will praise the individual doing the coaching more than the one doing the actual movement. I’m like, you’re doing an awesome job, you saw that even before I did, see that spot where their knee came in? That was perfect.

We make more progress with shorter rotations where the engagement is high. Athletes get so much better when they’re getting the feedback, says @joeybergles. Share on XWe’re having a dialogue while I’m walking along, coaching the whole group, and now they’re engaged and they’re seeing it—oh, I saw that mistake and now I’m able to help my partner correct it. If you never praise the coaching, will kids be motivated to do it? When we’re doing drills and other stuff, I make sure to praise the actions that I want to see—the coaching, the focus, things like that—because over the long run, those behaviors will drive the performance we’re trying to improve.

Freelap USA: When you’re doing speed, agility, and plyometrics with large groups in a large open space, there are very real challenges in terms of mapping how to start and space the athletes, how to maintain spacing with multiple kids all moving simultaneously, where do they end up and where do they start again, where do you intervene if something requires correcting.… How do you put all the variables together to design and execute that type of large group session?

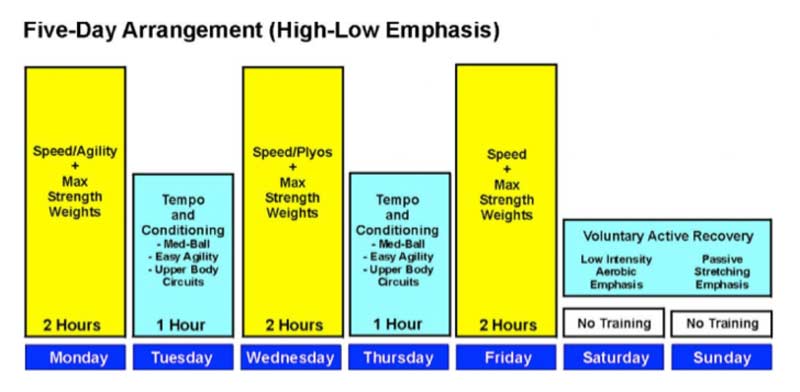

Joey Bergles: I try to look first at what the weekly schedule looks like. For example, it could be that we just have speed, plyo, or agility sessions, and other days it could be a combo where we’re lifting with those things as well. I can have 110 kids on a day—we have really good facilities, but when you have 110 kids from 14-18 of all different levels of skills and abilities, that’s extremely challenging in terms of organizationally making everything flow.

Looking at that week, then, I’ll progress the plyometric and speed work based around what we can actually coach. For example, if you’re doing a broad jump, there are some coaching points we’ll go over on a broad jump, but after we’ve been doing it for a few weeks or a month, I don’t need to provide a thesis every rep. You’re trying to jump out as far as you can, all right? Drive your feet through the ground and get out.

Everyone at every level can do that. But what if we’re doing a stationary triple jump or a stationary triple jump from an elevated box, which is a pretty advanced plyometric movement where you’re getting more velocity coming out of that first contact? Okay, first of all, there are only a certain number of athletes who physically need and can handle that. I’m not going to do a stationary triple jump with a 280-pound offensive lineman. So that would be an example of a bad exercise to do with a large group.

Where I’m going with this is, when I structure my speed/plyo days, when we go into a four-station rotation, on those days if we have a little bit more time because the groups aren’t that big, then I can get more teaching in about the intricate details of those movements. I can also modify: for instance, when the O-Line/D-Line rotates to that group, I have another plyo that they do in place of something like a stationary triple jump.

On the days when we have 35 minutes to do our speed/plyo work and then 35 minutes to go in and do our lifts, if I take 5-7 minutes to explain something to a group of 110 people, that won’t work. I don’t have a riser to stand on. When you have 100 people gathered around you, it’s a challenge for them to actually see what you’re trying to show them. A lot of people don’t understand if they’ve never done it before, but it takes a while for everyone to get spaced out and actually see, and now we’ve wasted another 40 seconds.

I like setting up our broad jumps, our squat jumps, our pogo hops, different rudiment hops. We can do those things in those large group settings. Maybe we want to do different sprints or resisted work, some type of acceleration, and then get timed on the Freelap…. We have 20 chips, and we can roll through quickly.

I speak fast and have a sense of urgency, so I can roll through things very quickly when it’s going on my pace. But we have to plan the stations so we’re doing resisted work here and timed sprints here and then we’ll flip-flop. We can’t get 100 people doing resisted sprints at the same time because we don’t have the equipment to do that.

I like to program out long term, 8-12 weeks if I can, and that’s where experience comes into play, says @joeybergles. Share on XI’m throwing all these variables out, but that’s how I look at the overall week and figure out what can we do on the specific days and then figure out the type of stuff we’re going to do. It might be that we’re going through a four-week block where we do potentiation work on one day. We have a facility that allows us to run a 10-yard sprint, so we’re potentiating that with our deadlifts. That then alters what we’re doing on other days. I like to program out long term, 8-12 weeks if I can, and that’s where experience comes into play. I can think of things that happened maybe five years ago at a college I worked at, and it was like, yeah, but we forgot to do this, and it created a massive issue.

If we’re running a 10-yard sprint, it’s not just the 10 yards, it’s how much space do they need to clear in both lanes? And, what’s the other drill on both sides? It could be a drill where there’s a ball being thrown, and it’s not supposed to go into that zone, but could it? Those are the types of factors you have to think through.

I like to draw it all out as diagrams so I can play out scenarios and figure out, oh, I’m going to need more space here, or we’re not going to be able to do this, or we’re going to have to switch these sides around. It’s almost like puzzle pieces, and it’s not just a matter of looking at it as part of a day, but I look at it over the course of a week.

Across the board, it’s not just a strength and conditioning issue; it’s true of most industries and organizations, they think they’re missing one specific thing. I need this drill, or I need this movement. And no, it’s probably how it’s actually being executed and how it’s being executed within the training program and where it’s being put in the training program, if it’s being run efficiently. If it takes 15 minutes to do it when it should take three minutes, that’s 12 minutes where you’re not doing something else that you could be.

Those are all factors that supersede the perfect movement. I could say great, we did the stationary triple jump, but I just saw it executed seven different ways. On the piece of paper, it said stationary triple jump, but his ground contact time on his first step was way too long, he overextended and was reaching, and it comes down to the coaching feedback and the execution and what we’re trying to get out of the actual training.

Freelap USA: When it was originally coined, the term “long-term athletic development” was being used for the process of developing Olympic-level athletes, but over time it’s often become a catchall for almost anything that’s the opposite of the specialized, year-round, “win today” club model in youth sports. How do you define LTAD and what major tenets of your definition inform how you train athletes from the younger levels on up?

Joey Bergles: How I look at long-term athletic development is similar to the Olympic model…. I’ve been fascinated with a lot of Olympic sports like gymnastics and training 3-year-olds all the way through to 17 and that thought process. So, when I look at long-term athletic development, I want the athlete to be their best and peaking when they’re 17 or 18 years old.

When I look at long-term athletic development, I want the athlete to be their best and peaking when they’re 17 or 18 years old, says @joeybergles. Share on XBecause, if you’re going to play in college, that’s when you’re getting a scholarship, and you’re going to be a varsity player—and we want our varsity teams to be the best. That’s what the ultimate goal is. Okay, you were good as a freshman, but does that mean your best freshman team will be the best varsity team in the district or the conference? No.

There are a lot of factors that go into it, but when I look at long-term athletic development, that’s the overarching goal in my head—if I’m working with an 8-year-old, what do we need to do over the next eight or nine years for them to be the best possible 17- or 18-year-old? So that if they do play in college or professionally or whatever it is, now that individual can take the torch and keep pushing their performance level.

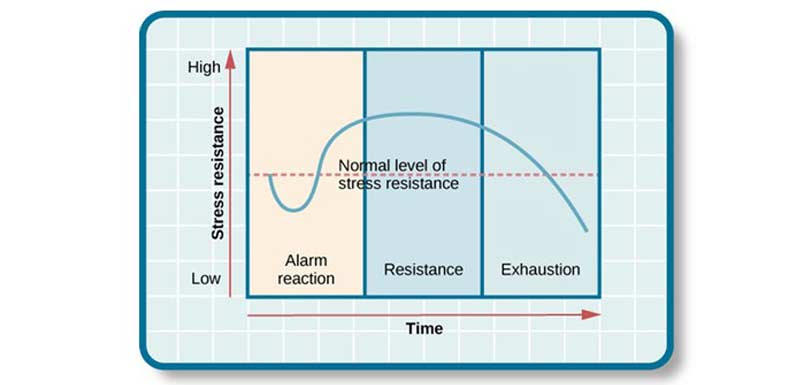

It’s a holistic approach to that goal. We see it now, it could be from social media and just parenting, but people want their 8-year-old to be the best 8-year-old in the world. Yet burnout is a legitimate reality, and if you’ve been doing structured training from 8 to 12, when you get to 12, you’re just like this isn’t fun anymore, I don’t even want to go to practice. Okay, THAT. Whatever your long-term athletic development program was, that’s horrible. You get an “F” for that. That should not happen.

Working with young kids, I want it to be fun. That’s the number one KPI. As soon as it starts becoming like a job, that starts that clock for this isn’t fun. Even for me, with our junior high age groups, there may be sprint training or other things I want to implement, and then I look around and they’re not paying attention and they’re not really into it—this might be what I think they need, but in a group of 40 or 50 10-year-olds, that’s where I’ve had to change what I do because first everything we do has to be fun. Then, I’m going to try to work the actual stuff I want to do into it.

Working with young kids, I want it to be fun. That’s the number one KPI, says @joeybergles. Share on XWith the kids I’m working with now, I’ve changed up the program like six times in six weeks. Every week it was going through a massive surgery. In my head, I thought it was going to work a lot better, but then you get out there with forty 9-year-olds and it’s like, oh man I thought they were going to enjoy that more…but they did not, they did not find that fun at all.

So, okay, cross that out.

From a long-term development standpoint, I look at stuff and think let’s make it fun, let’s make it engaging, let’s make them want to keep coming to our strength and conditioning activities. Then, as we get to 11 or 12 years old, we can start to sprinkle in more, and then when we get to junior high, we’re going to have to start doing more.

And as we get to high school…. Well, if I started with you when you were 10, and now you’re in high school, I’ve had you for five years. I may not know exactly where that individual is going to be at, but I can tell you right now they’ll be able to do a lot of things really, really well, and now I have another four years of actual technical physical development that we can do.

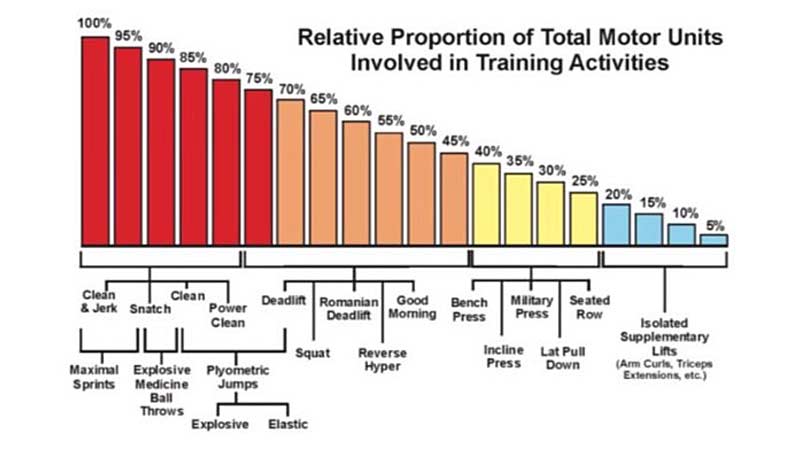

We went from kids should never lift weights and that mantra to hey, this is my 7-year-old deadlifting 190 pounds and post it and go viral on social media. Meanwhile, that 190-pound deadlift, that’s a rounded back, things are shifting. If you’re praising phenomenal technique and they may only be doing 50 pounds, that’s fine. But if I have a 7-year-old doing rounded-back deadlifts with a hip shift, okay, you’re putting some specific “inputs” into that system. There’s probably going to be a price to pay at some point down the line. It may be in two, five, or 30 years. And then you don’t need a specific mobility drill to fix it, you need to, like, go back to that previous point in time and not do that.

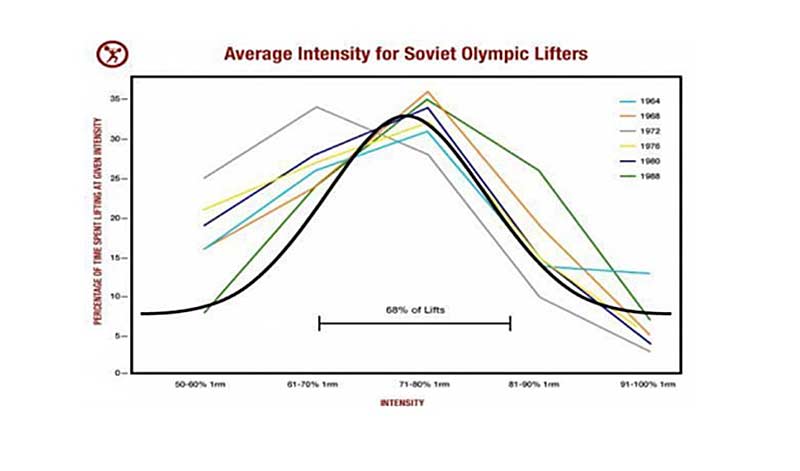

One of the things I tell people is that I like to develop strength, but slowly. Yeah, I’d like to have bigger jumps in numbers, but slowly is reasonable, and I know my technique will probably stay consistent. If I just say “we want to get strong” with 13-year-olds, I have a good idea what those squats, deadlifts, everything’s going to look like. But if we can just hit a 5-pound jump every month, I know the technique will stay good, and by the time they’re a freshman in high school, they’ll have solid strength. Now we can really start pushing because they have a skill and know what they’re doing.

That’s 100% a skill, and that just takes time. That’s not something you’re just going to be able to do in three months. So, when we look at that long-term model, it’s one of the skills we want to build along the way. Now, when we get two years down the line, and we want to do heavy clusters at 95%… if you’re not very good at the actual squatting technique, how effective do you think those clusters will be?

We’re developing those skills in a long-term model to get to those more advanced loading schemes. All of it’s a work in progress—this is the first time I’ve worked with 8-year-olds. And for like a month, I’d be driving home in my car thinking… that wasn’t bad, but it wasn’t quite up to the level I hold myself to.

Nine times out of 10, the kids’ favorite activity is timed sprints on the Freelap. There was a time when I thought we’d do the timed sprints only if we could get to it, but after a couple weeks where I was like this doesn’t work, this doesn’t work, this doesn’t work…the Freelap? That always works. So, you know what? That’s always in the session.

Freelap USA: Turning specifically to training varsity high school football players, choose one phase of the year—pre-season, in-season, off-season, whenever—and talk about a couple of new principles or exercises or pieces of equipment that you’ve added to your program in the past couple years that have made a notable impact, and how did you learn about those?

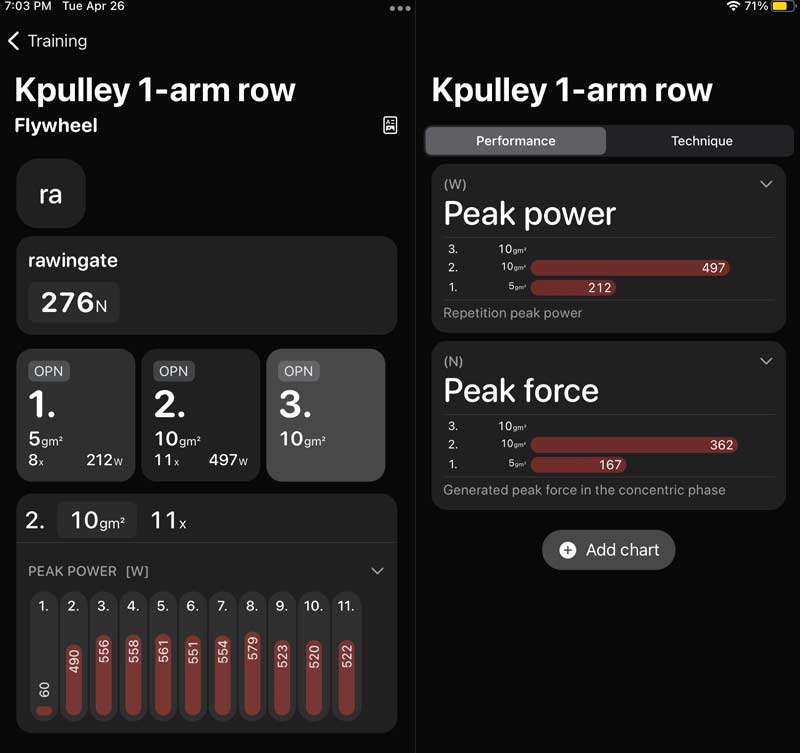

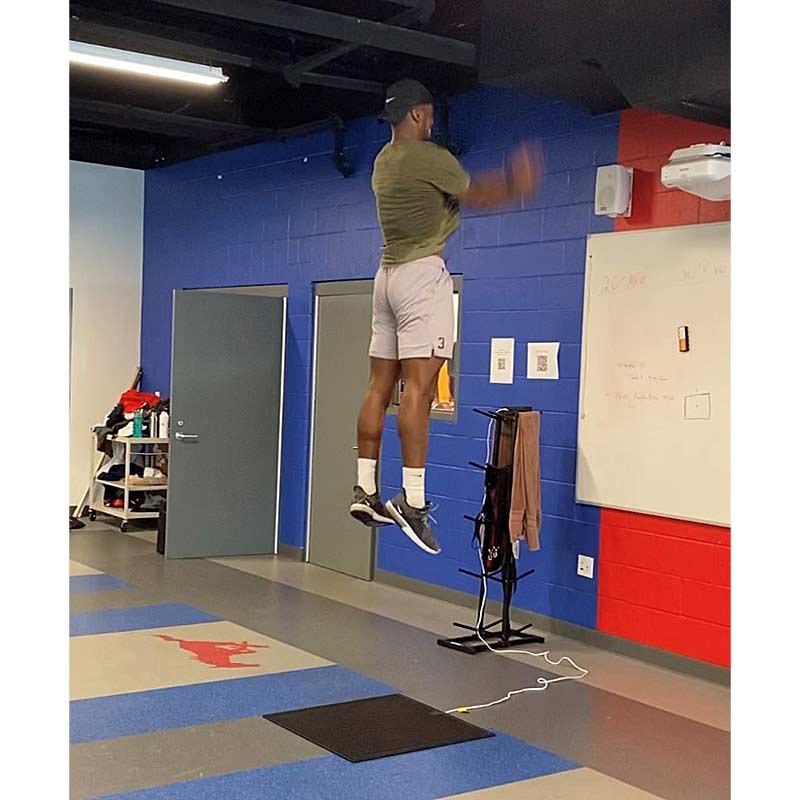

Joey Bergles: Going back to the Freelap system, we’ve had it for a little over a year now. We started with eight chips and have 20 now. It’s been a huge upgrade, being able to time sprints—the intent just goes through the roof. You’ll always have those self-motivated individuals who will be like even though I don’t know what my time is, I’m going to run extremely hard on this 10-yard sprint. But that’s not 100% of them.

The Freelap gives us the ability to time, and we track different stuff. I like short accelerations, so we’ll do a 2-yard build into a 10-yard sprint. We do different flys and max velocity with a 20-yard build, 30-yard build, different stuff like that—I like the versatility of it, different stuff like curved sprints that I have protocols for, measuring what different speeds are on curves, and the Freelap allows us to do that with the chips.

Incorporating the Freelap this past cycle, we did a potentiation cycle on our last day of the week with our deadlifts and that same sprint of 2 plus 10. In our weight room, we have a little bit of empty space, and then we have a garage door that opens up so we can sprint in the empty space and then carry it out through the garage door. There are different ways we time, whether it’s potentiation or our actual training session.

And I use it for everything, so it’s not just football—women’s basketball uses it, volleyball uses it, our junior high kids use it. We do it with our third through fifth graders. Everyone uses it, and everyone really enjoys it. It’s competitive, and kids are competitive with each other.

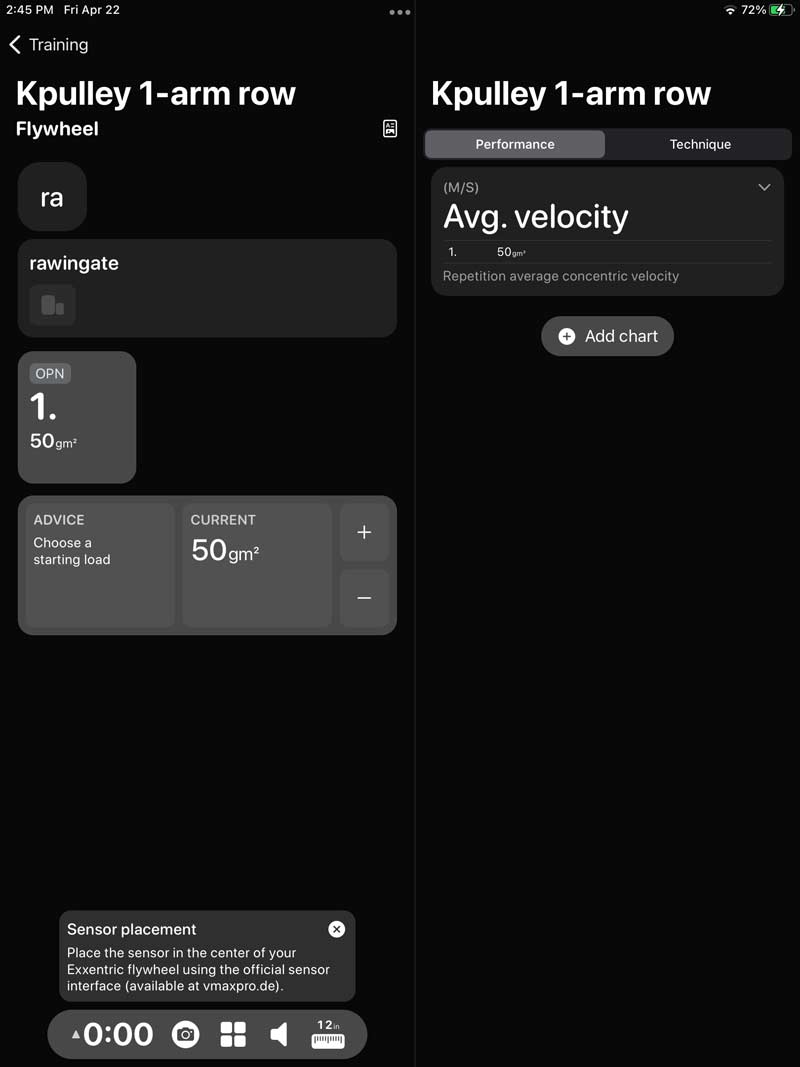

We also use the contact grid, and I really like how I can use that to see trends that I can then apply to a larger setting. We can’t run 100 kids through on a contact grid—that would take way too long—but I can look at trends that show how I might do different rep brackets based on what I see. It could be that I’m seeing pretty good data on reps 8 and 9, so why would I set my program for only five reps? That’s when I can apply data I’ve seen to a larger setting.

Freelap USA: In your personal career development as a coach, how do you approach continuing education and the ways you continue to grow as a coach? How do you view your responsibility to be a mentor and develop that wider coaching tree beneath you?

Joey Bergles: I was lucky with how I came up in the profession, because I was around mentors who took continuing education very seriously. With that, I saw firsthand that there was a lot of personal financial investment in continuing education.

I’ve seen firsthand the benefit of honing your craft, whether it’s speed stuff or mobility stuff, and I’ve had to pay for that information. That’s a reality, says @joeybergles. Share on XI know it’s kind of common for people to say, this is my continuing education budget, and if it’s outside of that, I’m not going to do it. But I’ve seen firsthand the benefit of honing your craft, whether it’s speed stuff or mobility stuff, and I’ve had to pay for that information. That’s a reality.

I’ve gone to New York City, I’ve gone to Toronto, I’ve gone to Southern California twice, and those were all just to learn more about mobility—and some of those were covered, and some I completely paid out of pocket. Not just the course, but also paying for a hotel, paying for flights, those have been investments I’ve made in the skill set I have. As a result, I’m able to do things.

When people ask, “how do you know how to do this?” or “how do you do that?” the answer is, well, I spent a lot of money on this. I can’t just give you a five-minute talk on how to do it…. If you could learn it in five minutes, then I’ve wasted a lot of money because I’ve made a substantial investment in myself. That’s the cold, hard truth.

That’s something I try to do every year. I just took Brett Bartholomew’s Art of Coaching and that wasn’t covered by my employer. I went to Austin, and that probably cost close to $1,500 between the course and the travel, and that’s an investment. Those are the things where, if I know it’s not going to be worthwhile, then I won’t invest my own personal finances in it. But I did research and going to that course was a good investment; it’s something that will help me for the next 30 or 40 years of my life. I’ve heard other people say it, if you’re not willing to invest in yourself, why would anyone else invest in you?

I also make a point of reading a lot, and I take a great deal of pride in the notes that I take. I don’t want to be the person who says, okay, I read 60 books this year, but I just sped through them and didn’t actually learn anything. Great, you read 60 books, but did you take anything from them?

So, I try to have a process where it’s pretty consistent. I want to read 15 pages during my workday, whether it’s coming in early or some time during the day, and then I want to read 15-20 pages at night. Then, I want to read around 30-40 pages on the weekends. The reality is, sometimes I’m not able to do that, 100% that happens. But 75% of the time I do, I spend those 45 minutes to an hour to get that reading done.

Over the course of the year, I structure that in. I listen to a podcast every morning when I come in to work, but when I go home from work I don’t—at the end of the day, I don’t want to listen to any information. At that point it’s music, because if I put on a podcast and it’s valuable information that I’m not ready to retain, then I’m going to miss it. So, I try to put the high-value material that I think will be critical to retain at the start of my day.

The same with my reading; my book in the morning will be more scientific-based and require more critical thinking, and my book at night will be more leadership, biography…the type of stuff that you don’t have to do a lot of in-depth thinking about. I like to read two books simultaneously: I have my at-work book and then the book I read at night.

I also spend some time on social media, and I’ll be honest, there are track accounts on Instagram where I’ll tell my other coaches, I found this track account in Estonia and they were doing this interesting plyometric drill with their high jumpers, and that’s the kind of thing that gets us thinking. That’s how I use social media now, finding these random, far-off accounts where I can learn about stuff I never would have known about otherwise.

That’s how I use social media now, finding these random, far-off accounts where I can learn about stuff I never would’ve known about otherwise, says @joeybergles. Share on XFrom a mentorship standpoint, when I was coming up, a lot of my early stages were self-taught. There are pluses and minuses to that—I had to figure out a lot on my own. That’s good and bad. I didn’t have someone helping me in certain areas, and that probably could have made me better both in the short term and the long term. But I also developed a skill set of I don’t need you to tell me what to do, I’m going to figure this out.

I got three racks, I got a hallway, and I’ve got 30 soccer girls? Okay, I’m gonna figure this out. Instead of having someone to bounce ideas off of, it was just okay, we’re gonna do this, and we’re gonna do this, and okay, that didn’t work, so now we’re gonna try this, and okay that worked really well so we’re going to stay with it.

With that, I have a lot of respect for individuals who are self-motivated, the ones who are like hey, you didn’t tell me to do this, but I did this, this, and this. That’s the person I want to teach what I know. If you’re expecting someone to hand you something, I’m probably not going to do that.

Both in terms of the financials and what I’ve spent to acquire the knowledge that I have, plus all the hours I spent doing things like being on YouTube way past midnight when I was 22 just trying to learn what I needed to know. If you’re a younger coach or an intern with a mindset that you just kinda want to do this but haven’t really made a whole lot of investment, then I am not going to give you everything I have until you make that investment on your own end.

It’s just like that idea of engagement with the athletes, that coach who’s invested and that light bulb goes off—they are the ones who, 20 years down the line, will have taken everything and run with it. But if it doesn’t matter that much to you, it’s not going to have that long-lasting effect.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF