Nico de Villiers is a South African high-performance coach and manager with a strong background in rugby and netball. Coming originally from university sports, Nico has led the S&C programs for a number of international representative sides, including South Africa and Zimbabwe. Currently, Nico works as an S&C coach and rehab specialist for the DHL Stormers, a rugby franchise that plays in the United Rugby Championships and consists of teams from Ireland, Italy, Scotland, Wales, and South Africa. He has coached various World Cup-winning rugby players with his science-informed approach.

Freelap USA: You’ve coached many World Cup-winning rugby players, who are not only incredibly strong but also very powerful. Can you share your approach to power development and what you emphasize pre- and in-season? What technologies do you use for assessing and monitoring the effectiveness of your approach?

Nico de Villiers: When I look to develop power, I follow three main principles:

First, I try to be “velocity specific.” That means we target specific training qualities based on the velocity of movement. I have, however, found that adaptations are ultimately determined by the effort exerted by each player during training. If a player does not complete a movement with the highest velocity possible or with maximal intent, the power produced during that movement will be insufficient to create true performance improvements. Maximal intent is likely the most critical aspect of improvements in power production.

When I look to develop power, I follow three main principles: I try to be ‘velocity specific,’ I am movement specific, and I try for when players are as fresh as possible. Share on XSecond, I am movement specific—meaning that my exercise selection for power development is tailored to the type of adaptation I want for the player. Here are some exercise movements I use to target specific adaptations:

- Ballistic movements like various loaded jumps are very effective for developing force at various velocities.

- Weightlifting derivatives for rate of force development.

- Unloaded jumps and plyometrics for elastic qualities and getting stiffness through the system (mostly for the faster players).

- Compensatory acceleration exercises (like bands and chains) for more strength-speed development or late RFD.

- Accommodating resistance jumps where we try and overspeed a player and triple extension pattern to develop early RFD.

Lastly, I try and develop power when players are as fresh as possible. Fatigue really is the enemy of power development. If a player can’t produce high outputs, chances are they won’t get the stimulus or adaptation from the session to get more powerful.

Pre-Season vs. In-Season Power Training

During the pre-season, we try and maximize our power development by exposing players to higher volumes of high output training. To ensure players get max volume, we make use of velocity cut-off sets. This maximizes the amount of work players can do above 90% of their best rep for the day. Once a player can no longer get above 90% of output, we terminate the exercise.

During the in-season period, we really must try and minimize fatigue while still getting some adaptation. We look for opportunities in the season where we can push a bit, like when the team has a bye week or there is a drop in running volume. To ensure high intensity with low volumes, we reduce the velocity drop-off to 5% or do more cluster sets. It is important that we still get high output during the in-season because power output, if not exposed to regularly, can slip away easily as the season progresses.

Technology has become a major part of our training system over the last few years. We are privileged to have a couple of Gymawares and some force plates.

We found force plates to be more accurate, and we use them to assess players and give them a power profile. We also do a bit of neuromuscular fatigue assessment with the CMJ during the in-season to help with jump volume prescription and determine whether we should push or pull a player back a bit.

Gymaware is used more to monitor players’ progression and velocity drop-offs in sets. It also creates great competition, and this has a direct impact on players’ intent.

Freelap USA: If you look at your programs from the last few years, is there anything that has worked particularly well for developing power in your players and anything that hasn’t worked the way you’ve planned it? What were the reasons for that?

Nico de Villiers: Creating competition! In the very dynamic, chaotic environment of team sports, you often must use simple methods and just ensure that the players are motivated and produce sufficient output in the lifts to stimulate adaptations. The thing I found works the best for this is creating competition. Crack out the Gymaware, the leader board, and the celebration bell that you can ring if you hit the PB, and you are almost guaranteed to have a good session.

If I have more of a controlled environment with a smaller group, I have found velocity cut-off sets and high-volume power training to be very effective methods to develop power. Share on XIf I have more of a controlled environment with a smaller group, I have found velocity cut-off sets and high-volume power training to be very effective methods to develop power.

I mentioned velocity cut-off earlier. This is basically setting up the Gymaware to indicate if a player has dropped below a certain velocity threshold (normally the best rep for the day). The percentage drop can be between 5% and 10%, depending on the volume of work you want to do. (The higher the threshold, the more volume the players will do and the more fatigue it will cause.)

The reason I like these methods is that, based on the neuromuscular status of the players, they will do the optimal amount of high output volume that they can tolerate that day. If a player is feeling fresh, they are often able to keep the intensity above 95% of their max for up to 15 consecutive reps, while a player who is more fatigued will only be able to tolerate 2-3 reps. At the end of a session, some guys will get more than 30 quality high-output reps, while others will get less than 10 reps. When we can push players who are fresh a bit, it gives a potent stimulus, and we see good results as the back end of this.

Another quite potent stimulus we use (sparingly, I must add) is something called high-volume power training. This is a method I adopted from Dr. Alex Natera’s work. This method is characterized by:

- High volume sets (10-15 reps)

- Multiples sets (60-180 reps)

- Moderate- to short-interest recovery (30 seconds-2 minutes)

- Light to moderate loads (30-50% 1RM)

- Ballistic or weightlifting movements

- Big velocity drop-off (15-35%)

- Max effort and max intent on each rep

I use this method on select players for two- to three-week blocks to give them a novel stimulus if I want to address power output quickly (end stage of rehab or having a bye week).

In terms of things that did not work well, it usually boils down not to what you do, but how you do it. If players are not lifting with intent and producing high output, then they rarely improve their power capabilities. Whether it’s Olympics lifts, loaded jumps, banded squats, or contrast/complex methods, it all works, but only if we follow the principles of being velocity-specific, have max intents, and do this while players are reasonably fresh.

In terms of things that did not work well, it usually boils down not to what you do, but how you do it. Share on XFreelap USA: What are the biggest myths and misconceptions about power development for team sports?

Nico de Villiers: I would say the biggest misconception is that power development looks the same for all players in a team sport. We tend to think of fast movement with light weights or see weightlifting exercises and classify it as a power development session, while power development depends on how we address the neuromuscular system and what we are trying to get out of it.

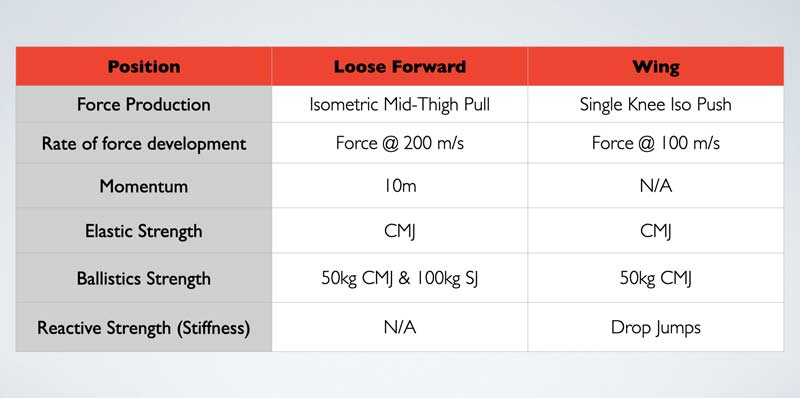

Ultimately, the goal of developing power is to improve output in a specific sporting task on the field. The way we develop power for a loose forward in rugby who needs to dominate collisions and the way we develop power for a wing who needs to express max speed are very different. Both need to express force, but the time constraint to do so will be different.

Doing some diagnostic testing often helps us determine what neuromuscular properties need to be addressed so that the players will produce max output in the task required of them.

Here are some of the different diagnostics tests we look at to determine the power development plan each player needs based on their position.

From these diagnostics, we can determine what each player needs in their position to be powerful on the field for us. So, developing power for a loose forward who has very good force production but poor elastic ability will look very different from a wing who has great reactive abilities but can’t generate lots of force into the ground.

We often find that players have great neuromuscular abilities, but they still do not transfer them to the sporting task. Then we will look at developing movement skills and work with either the coach or a specialist to see how we can transfer the athlete’s motor potential abilities into the sporting task. For these players, power development will happen outside on the pitch and not in the weight room

Freelap USA: Your role at the Stormers also includes return to play after long-term injuries. You’ve had a few players with neck injuries successfully return to playing rugby. With collision sports like rugby or American football being at high risk for these kinds of injuries, what are the key aspects from a physical and mental perspective that coaches should consider for successful rehabilitation from a neck injury?

Nico de Villiers: Neck injuries can be very tricky due to the high risk if something goes wrong, which could end a player’s career. The other issue with neck injuries is, unlike other body parts, there is no real, established phase-based return to play protocol. When assessing the neck, it’s difficult to give exit criteria and KPIs for each stage to determine if a player is ready to play or not.

From a physical aspect, we consider multiple variables during the player’s return to play process. The goal is that a player should be able to produce, absorb, and transmit forces through various planes of movement through a safe range. This should also be done at various velocities where there is a time constraint on force production. To add to that, we look at moving from a controlled to a chaotic environment, where the player is exposed to the high-risk skill that they need to execute when they play.

Below is an example of how we progressed a front row player in rugby after neck surgery and prepared him to scrum and to be able to handle contact like tackles:

- Restore both inner and outer range of motion (in front row forwards, this is often limited, so we need to know the player’s limitation).

- Restore various force capabilities in various planes.

- Isometric strength by preventing lateral flexion, flexion, extension, and diagonally.

- Force absorption (eccentric strength) in lateral flexion, flexion, extension, and diagonally.

- Force production (concentric strength) in lateral flexion, flexion, extension, and diagonally.

- Restore rate of force development and producing various contractions quickly in various positions. Can be done by pushing with hand, pulling with a towel, or throwing physioball against the head.

- Introduce more unpredictable force and challenge the player to do this while performing another task like, for example, crawling variation to mimic scrum position while applying various forces in various planes on the neck.

- Reintroduce skills at low intensity and high predictability and then progress to higher intensity with less control. An example of this would be the player doing 1v1 scrumming until they are comfortable to do so at full intensity and then progress to 2v2, 3v3, full pack against machine (high force, high control) to full pack static hold (high force, moderate control) and eventually full-on scrums.

From a mental aspect, it is very important that technical or skills coaches get involved as soon as possible. Neck injuries often occur because players get themselves in a bad position on the field. Coaches reintroducing them to good technique, timing, and progressive intensity play a big role in establishing the player’s confidence. Even in cases where we, as coaches and physios, believed the neck was physically strong and ready, the players only believed in it once they were able to execute the skill or collision with confidence. Tackling and scrumming technique training help a lot to reduce anxiety to go and perform the skill once they are in an uncontrolled environment.

Neck injuries often occur because players get themselves in a bad position on the field. Coaches reintroducing good technique, timing, and progressive intensity reestablish player’s confidence. Share on XFreelap USA: When playing a long season and players start dealing with lower body “niggles” like minor hamstring or calf injuries, how do you react and adapt with your program design and load management?

Nico de Villiers: In a running/collision-based sport like rugby union, you will always have players with niggles. Some research has even indicated in professional rugby league players, no players reported being pain-free at any stage of the season.1 For me, the priority is to make sure that we get a good diagnosis of the niggle. This might sound obvious, but often if the diagnosis is not accurate, the intervention, whether that is rest or load management, could place the players at a bigger risk of sustaining a more severe injury.

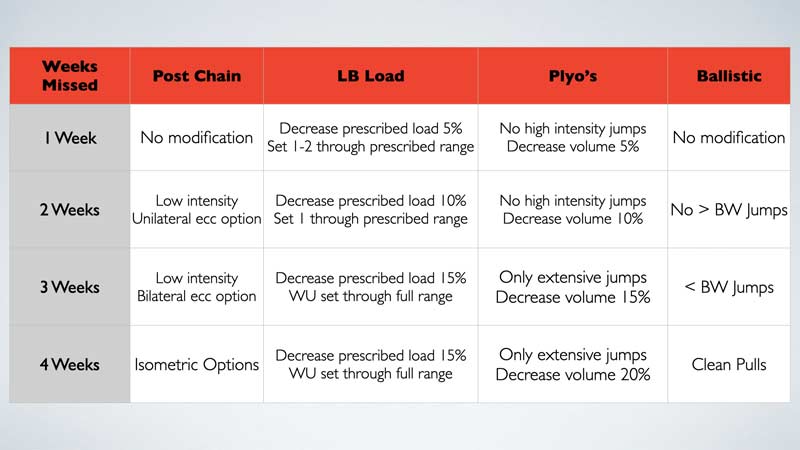

When dealing with minor injuries around the lower body, the first step would be to deload them and make sure that the player is ticking their recovery boxes (sleep, nutrition, hydration, managing external stressors). It’s funny how often these niggles appear when there is a change in a player’s lifestyle and recovery efforts go out the window. When we deload, it could be in various ways, either managing running exposure (no high speed or change of direction) or pulling them from field training altogether. When players are still able to run, we may deload them in the gym for a week or two and then gradually expose them to gym load again.

It’s important that when we deload a player with a niggle, we don’t detrain them. Often, players who present with a calf, adductor, or hamstring niggle are pulled from training until the discomfort settles, but when reintroduced to training, they are reluctant to do strength work in that area. Depending on how long a player has not been exposed to a stimulus in the gym, we will have to expose them gradually back to normal training to ensure we keep load through the tissue without overdoing it.

Below is an example of how we could reintroduce a player back to gym load after a short management period due to niggles:

References

1. Fletcher BD, Twist C, Haigh JD, Brewer C, Morton JP, and Close GL. “Season-long increases in perceived muscle soreness in professional rugby league players: role of player position, match characteristics and playing surface.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2016;34(11):1067–1072.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF