Velocity-based training (VBT) is growing exponentially at all levels of strength and conditioning, especially as reliable equipment becomes more available financially and analytics technology becomes more user friendly. Still, the data on athletics-wide use is limited, as nearly all published works are team or club level, as opposed to 13 sports teams in a single athletics department. However, the signs are currently present to see the full integration of using VBT athletics-wide at all levels of strength and conditioning both as feasible and viable.

While most research will emphasize methods, subject populations, and a slew of coding and analyses, this article will be more focused on our “real life” experience adopting VBT athletics-wide in a high school athletic setting and follow the course of:

- Here is the gap in knowledge and the problem we identified.

- Here is the information and interventions available to fill the gap and fix the problem.

- Here is what we did and what worked for us, this is what did not work for us, and here is what we will adjust going forward.

We did not reinvent the wheel. Rather, we have just taken a different approach in an endeavor to make the wheel turn more efficiently. All in an attempt to keep it simple and transparent to move the field forward, instead of how elegant and complicated the topic can be made and challenging to replicate.

1. The Gap in Knowledge

We are very fortunate to have a strong support staff, including two athletic trainers, two full-time strength and conditioning coaches, and many coaches and athletes that are weightroom literate. We had what we believed to be a good handle on many aspects of strength and conditioning—so much so, that we scratched “strength and conditioning” and transitioned to “performance training.” Not that we reinvented that wheel, but more of an omen for a new, forward-looking mindset of developing and evolving into the future.

One aspect that was missing was while we felt our program to be effective at developing strong and well-conditioned athletes, we thought we could be more athletic and explosive overall. We came to this conclusion as we had solid performances on the field, but other teams seemed just a bit more explosive—so, we made the move to VBT to fill that gap to have strong, well-conditioned, and now optimally explosive athletes.

What’s Out There to Address the Gap?

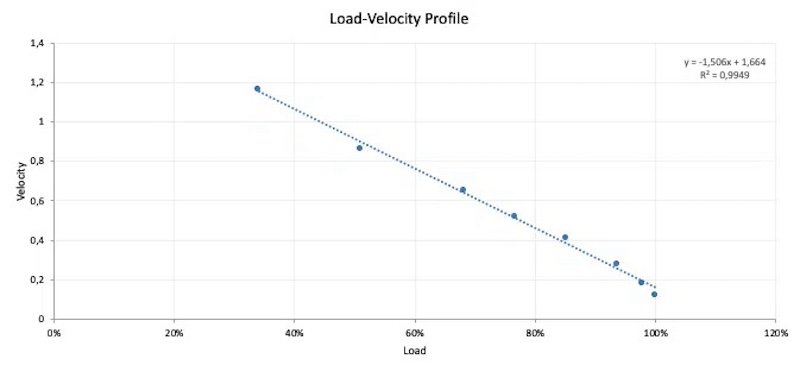

One key aspect that we could improve on was transitioning away from traditional strength and conditioning and evolving into a VBT program. We wanted to get better at moving and producing powerful, explosive movements that we could more accurately measure beyond one repetition or plyometric maxes and percentages.

We wanted to get better at moving and producing powerful, explosive movements that we could more accurately measure beyond one repetition or plyometric maxes and percentages, say @KyleSouthall1 & Summer Jones. Share on X

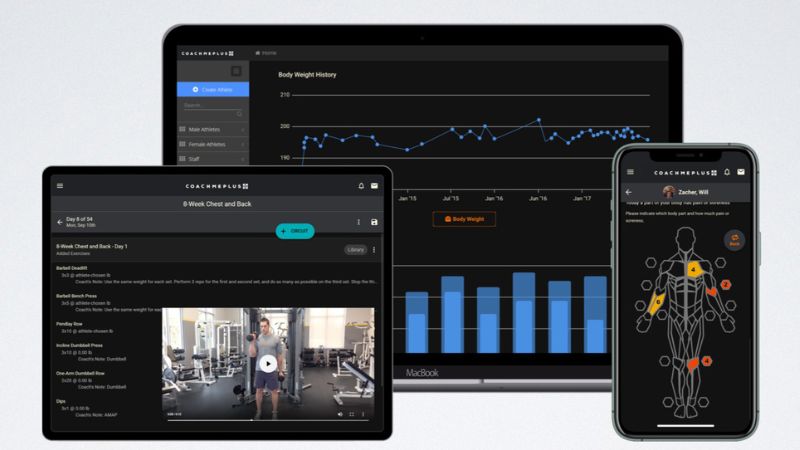

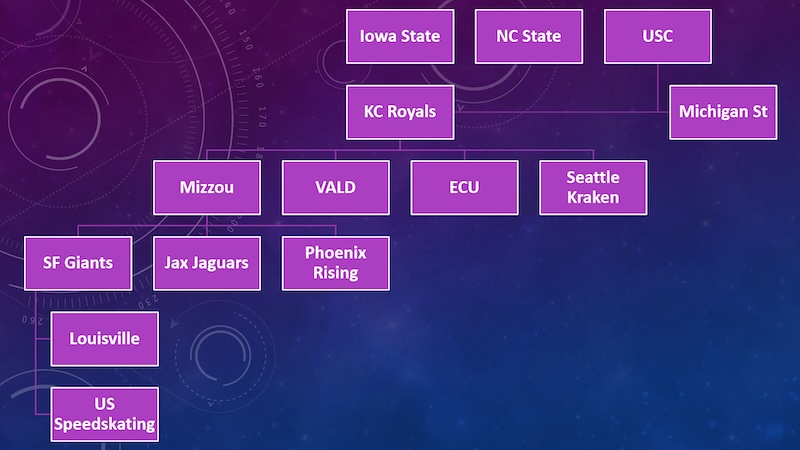

We trialed four different types of VBT and ultimately chose Vitruve due to the ease of use—both by athletes on the floor and for us on the coaching side in downloading and analyzing data, easy integrations into our athlete monitoring system, and price point. Thanks to many donors who believed in our vision and contributed on our annual day of giving, we were able to purchase 16 Vitruve Encoder Units, one for each weight rack in our main weightroom.

2. What We Did With What Was Available and What Worked for Us

The first thing we did was start small. We met with various entities, ranging from peer high schools to international level strength and conditioning coaches, performance staff, and sports scientists. We took in all the information and cooked it down to what we could handle with our resources and staff size.

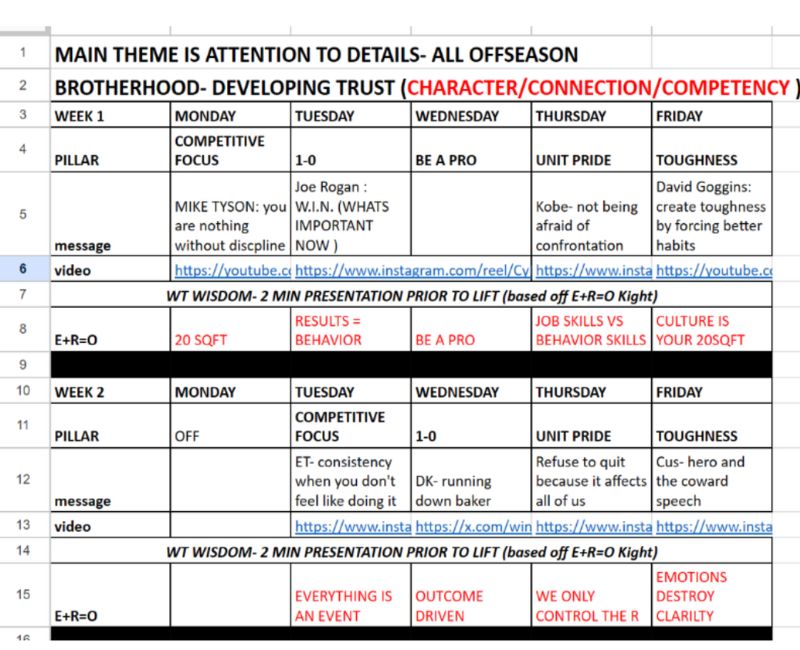

What we quickly learned is that we could provide a great service to our athletes—all of them! We started with football and boys basketball as our experimental group. Delving into years of data, both objective and subjective, we boiled our foundation exercises down to 10 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that translate from the weightroom to the football field and basketball court. We took those and centered our training programs around maximizing their efficiency, using velocity-based metrics and scrapping maxes and percentages (see Table 1 below for the Top 10 KPIs that fit our situation the best).

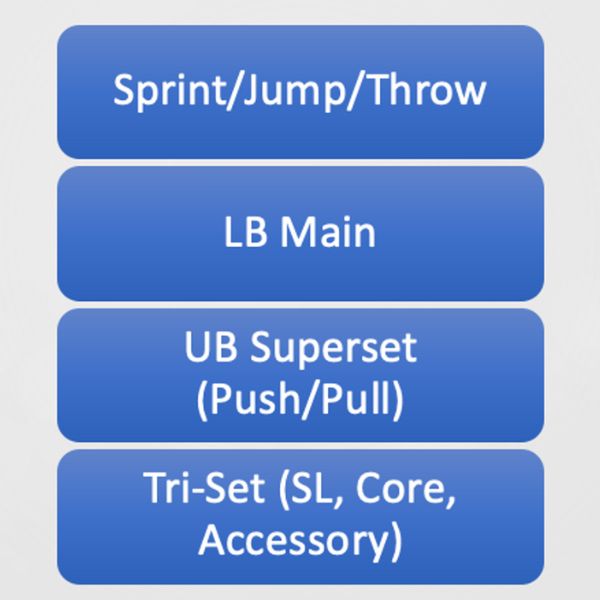

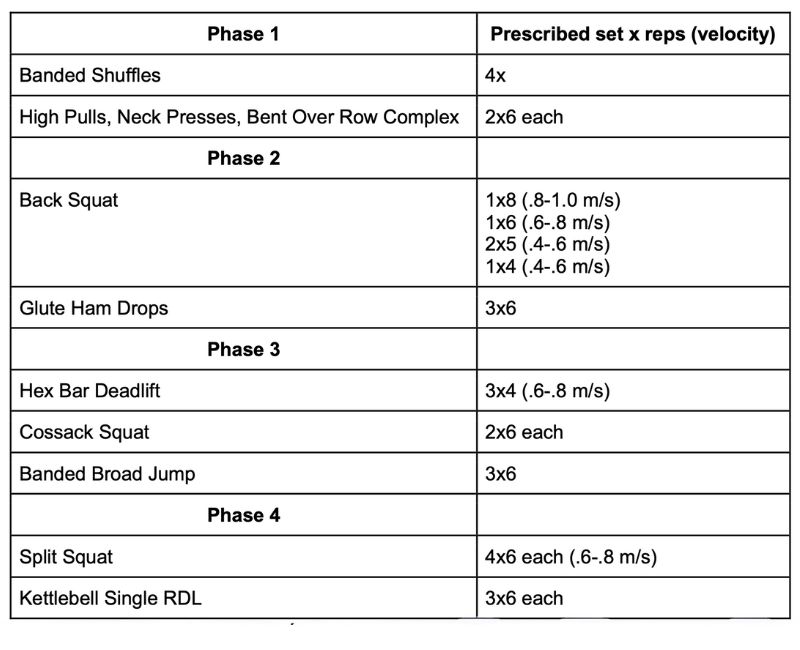

Once we narrowed this down, we got to work using these exercises and their variations as the foundation of our performance training program. Our intention is to use VBT for two to four exercises each session in the weightroom (See Table 2 below for an example of our implementation and programming).

Key Context: For this workout, we had 16 racks of three to four athletes with a total of 68 athletes (four were rehabs with modified workouts). One athlete lifts, one or two rest/spot, and one does the auxiliary lift—then, rotate. This took 50 minutes to complete, including dynamic warm-up/primers, weightroom setup, workout, and clean up.

Once we felt good about the logistics and programming, we added volleyball, girls’ basketball, girls’ soccer, and boys’ soccer. We will continue to add sports until we get everyone who wants to be in the program fully integrated into the program.

One key thing that worked for us is to keep it simple and start slowly. Kids these days are very technologically savvy. Consequently, there was a minimal learning curve beyond becoming familiar with the program itself—but that time, one day, was very valuable in making it work smoothly. Another thing that worked out really well for us is creating leaderboards. The leaderboards brought out the competitive nature in our athletes and were instrumental in buy-in. We found multiple athletes in the weightroom between classes, etc., looking at leaderboards.

One key thing that worked for us is to keep it simple and start slowly. Kids these days are very technologically savvy. Consequently, there was a minimal learning curve beyond becoming familiar with the program itself. Share on XWhat Did Not Work For Us

We had our share of aspects that did not work that were valuable learning lessons. Some are very simple, some very complex, and all valuable in the end.

- We learned that while programming is important, it’s especially important in VBT. Our first day we planned to keep the workout the same as before, but measure two KPIs in a superset. Sounded great in theory…until we learned that moving the encoders and on the fly changing the programming was challenging. An easy fix: rearrange the order of super sets. Hindsight is often 20/20.

- We ran into the technological issue of the program being on iPads at each rack but our analytic programs, such as SPSS and MatLab, being on HP systems. Our workaround for that was simply exporting the data into Google Sheets and creating the leaderboards referenced above.

- The mass of data we get. On top of already having 80 Catapult Global Positioning System (GPS) sensors, injury epidemiology, and operational data, this system gave us a lot of data! Any given week at Briarwood, we max out an Excel sheet (roughly 1.05 million data points). In three years, we’ve collected 3.21 billion performance and medical related data points on 811 athletes. The first step is management—what is important? Luckily, we were able to see everything we needed to see from a coaches’ and athletes’ perspective in Google Sheets. That is a huge testament to the user-friendly upside of Vitruve.

Lastly, not so much what didn’t work for us, but rather something to help us going forward is identifying standards or baseline requirements within our performance training program. To be an athlete in “X” program within our athletics program, an athlete should be able to do W-strength, Y-mobility, Z-speed, and A-agility. Once the athlete can achieve these minimal standards, you “graduate” into the full-blown VBT program.

In the meantime, you address those deficiencies and work on foundations to allow you to safely experience the forces and other demands VBT places upon the body that are unique. We already have a similar process of teaching our young, junior-high-aged athletes the proper form, etiquette, and terminology, and we assess these before they are fully integrated into the performance program. VBT offers a more objective measure to a process that we institute starting in the seventh grade.

What’s Next for Briarwood and Velocity-Based Training

Now that we’ve found a system and it is working, we are in the wait part of “hurry up and wait.” Our plan is to let the system run for a month using boys’ basketball and football as our guinea pigs. Then, we’ll thoroughly evaluate all aspects of the program in respect to improvements, obstacles, and the wants, needs, and values of our stakeholders. Following that, we’ll repeat in three-month cycles, doing all we can to adjust and provide an elite service to our clientele.

Now that we’ve found a system and it is working, we are in the *wait* part of *hurry up and wait.* Our plan is to let the system run for a month using boys’ basketball and football as our guinea pigs, says @KyleSouthall1. Share on XLike all good research, thus far we have more questions than answers in our time using Vitruve. For example, we have four years of very highly detailed injury data. How will VBT affect this aspect compared to traditional training over the next four years?

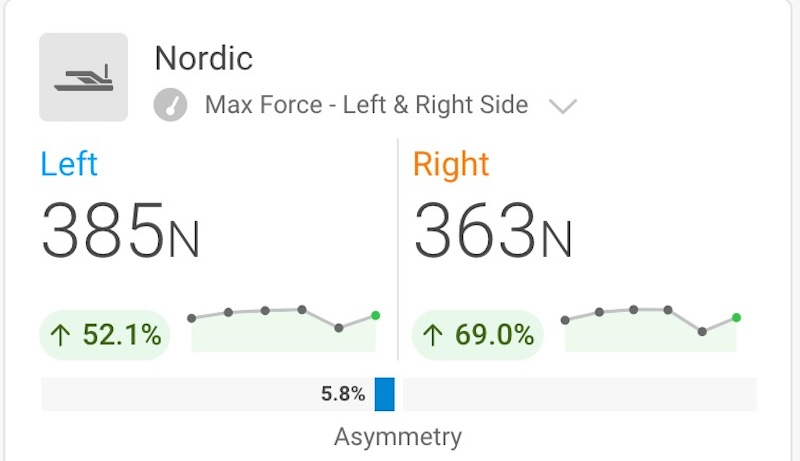

Another thing we have seen is asymmetry in single leg exercises using VBT as a measure. This is a promising technique we are exploring to be able to quantify asymmetries if force plates, motion capture, and other technologies are available. One more unexpected insight was how valuable it is for our advanced-phase rehabilitation athletes. We are able to prescribe exercises that expose them to more realistic athletic forces while keeping the loads in a safe range. Not that this is new—late-stage rehabilitations are, or at least should be, common in the weightroom. VBT allowed us to quantify a historically subjective aspect beyond weight on a barbell.

We’re learning the translational skills and tools that are preparing us for techniques and technologies that have not even been invented yet, say @KyleSouthall1 & Summer Jones. Share on XRegardless, we feel that this will benefit our athletes, be a great learning tool for our students, coaching staff, and interns as we grow into the future of performance training. We’re learning the translational skills and tools that are preparing us for techniques and technologies that have not even been invented yet. Listen here for a brief overview of our adoption of VBT into training and a coach’s perspective on the shift.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Summer is a six-month strength and conditioning intern at Briarwood Christian Schools, where she assists in all aspects of the performance training program while finishing her Bachelors of Science degree in Exercise Science from Samford University. She has been instrumental in the development of programming and the implementation of Velocity-based training at Briarwood Christian Schools.

Summer is a six-month strength and conditioning intern at Briarwood Christian Schools, where she assists in all aspects of the performance training program while finishing her Bachelors of Science degree in Exercise Science from Samford University. She has been instrumental in the development of programming and the implementation of Velocity-based training at Briarwood Christian Schools.