How do you get there from here? Perhaps, as a coach or an athlete, you have been in this place: you’ve become frustrated with what you are doing because you know roughly where you want to go, but can’t seem to get there. And whatever you are doing here and now just isn’t working.

Performance ceilings are a common challenge, either in terms of training or competitive goals; if nothing you do seems to be leading to improvement, what can you do to break through?

If nothing you do seems to be leading to improvement, what can you do to break through? Share on XThen

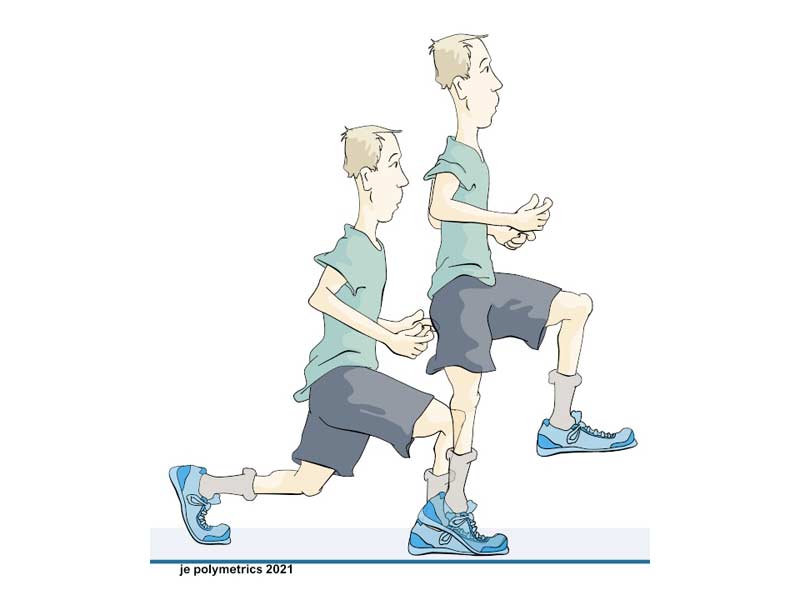

As an athlete, I recall a here/there period of time in the context of power-speed development. In the pre-competitive phases, we performed a diverse package of leaps, bounds, and hops two to three times per week. Leg exchanges (a bouncy advancing lunge with an alternating stride pattern) were an oddity in the mix. Although they didn’t imitate running, we were told that stride development would benefit. We might have done two or three variants in a session.

Video 1. Split-leap exchanges with the athlete advancing horizontally.

Video 2. Lunge-leap combination.

A related exercise group were lunge walks, a slow and almost goofy walk combining a low lunge and tall unilateral stance. We used these as activations or inserts. The common factor for me was that I could not perform any of the slow variations without falling over or clenching so strongly that I could barely move or breathe.

I became competent with the leaps and bounds, but for one factor: increased ability in these exercises did not translate to targeted skill improvements. Neither takeoffs nor sprint times showed any improvements for all the time invested. On assessments such as five hops, distances stayed much the same and left-right imbalances were still obvious. I looked smoother and improved my capacity, but of course in power-speed sports there are no bonuses for looking good.

Others within the group improved, but my here never inched towards there. I tried to hit the ground harder, thinking it would add to takeoff landing and takeoff intensity. My ankles and feet were in pain. I tried more, with additional sessions…recovery suffered, sleep became fragmented, everything hurt. There was drifting away—this was a downward spiral of dissatisfaction and injury.

In hindsight, clues to why this was happening were in the slower work, with the faster work showing the outcomes. I did not have the language or understanding to figure it all out and was in a situation that was unable to provide options. It was FOFY (find out for yourself) time.

I did not have the language or understanding to figure it all out and was in a situation that was unable to provide options. Share on XChronic ankle sprains (mostly from basketball) had left me with poor static balance and dynamic stability.1 Out of anxiety, I avoided uneven terrain (even cracks in the pavement), lateral work, and quick directional changes. From another perspective, the program was good, probably ahead of its time…but if the athlete is not ready for the program, there will be little development. In this situation, I was not ready and did not have the full capability to manage the complexities of the program or the need for speed over the ground (see Frans Bosch’s Anatomy of Agility for more on the constraints-led approach).

Out of puzzlement and wanting to diminish growing negativity, I began to work on slow lunge and split squat variations (for me, lunges have an airborne phase for one or both feet rather than being statically anchored). The two exercises morphed into an up-down hybrid (see illustrated self-portrait below).

At first, I needed wall support and was very tense with co-contraction anxiety. The issues with stability and balance were immediately obvious, and with the slower work there were no places to hide or compensate. Looking down at my front foot, I could see that the tibialis anterior was twitching all over the place—something I called the “Tibs Dance.” My torso and hips would twitch and sway side-to-side, unable to find a stable center, and my feet were passive paddles.

What the hybrid lunge challenged me to do was develop stabilizing networks, from foot to hip to torso, and enable these to work with higher force-velocity components. One insight I gained was that it was all the little stabilizers that were limiting development—I had to shift perspectives from training big muscle movers to also including stabilizers and synergists. I had to learn to move with ease while balancing.

We are increasingly living in a manufactured world of smooth terrains and firm surfaces. Humans are built to deal with variable terrains and unstable surfaces at speed, but only if they train the skills. Only if they reduce their own joint and movement variability for a particular skill set. I had avoided this for years.

Humans are built to deal with variable terrains and unstable surfaces at speed, but only if they train the skills. Share on XChronic injuries teach us that restoration of function is more than being pain-free; we need to reframe our mechanics, rewire our headsets for neuromuscular enhancement, and reformat our physiology so that the big muscle chains cannot overwhelm the stabilizing networks. In the storyline, the rush to resume training and the pressures from systems to resume competitions were always doomed to ceilings and chronic pain. We carry our injury patterns forward unless there is an intervention for change. This was personally tough to accept, but pain can be a powerful motivator.

Now

Circumstances have changed for coaches and athletes since the timeframe of that story. The internet makes more information readily accessible and coaching education is better and more collaborative. There is more applicable research becoming available, coupled with insightful analyses. We can also do more of what I would call “cultural crossovers” from sport to sport, gathering up little nuggets of insight. Further still, there is more opportunity to tap into systematized training as opposed to cherry-picking isolated exercises or copying the patterns that someone did in the past that might have worked.

However, we have also learned that things like pandemics change access and interaction. We need better critical thinking skills to weed out speculative or faulty training suggestions from the mass of information we are bombarded with. We are all learning that fact checking needs to be a part of the decision-making process to ensure that performance and prevention needs are not lost. In some ways the “here and there” conundrum can still emerge and frustrate us.

Lunges and split squats have retained their validity over time. They offer that assessment-remedy framework that I tapped into in the past. I look at them as complementary work, bridging a gap between slow and fast as well as bilateral to unilateral supports. Today, as a coach and mentor, I divide complementary work into subsections of preparation. Preparation, to my thinking, runs parallel to training and competition readiness and never leaves the program. What I was doing in those ages past was what I would now term “preparation to move.”

Lunges and split squats have retained their validity over time. Share on XThe hybrid lunge mentioned in my story has a major limitation: diminishing returns on time invested once the foundation of balance and stability have been developed or reformatted—they turn into air squat equivalents and dozens of reps. The traditional pathway would add external overloads to the bodyweight work, but these too come with both limitations and precautions. As a coach, I needed a better way to bridge the gap between foundation body repetitions and higher force-velocity skills.

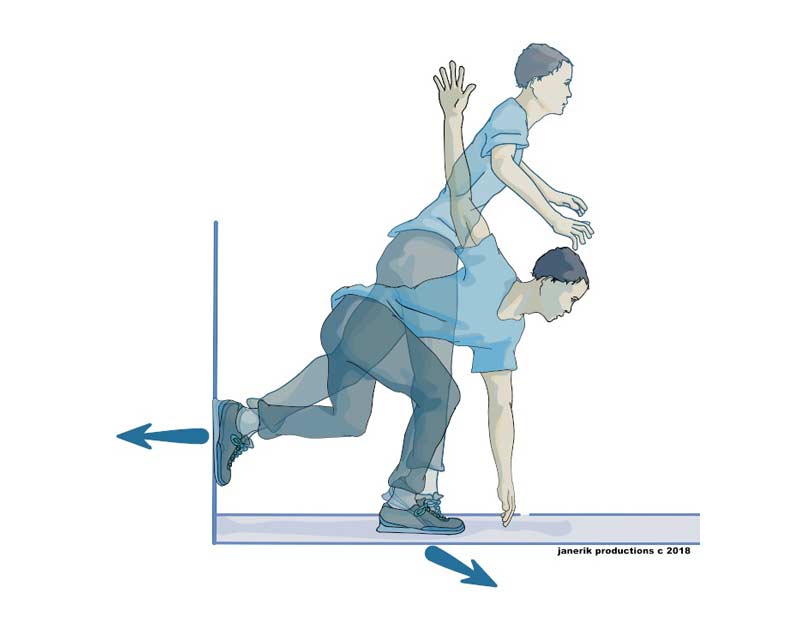

My solution, taken from historical conditioning formats, other sports, and athletes themselves, was to devise ways of increasing force within the body rather than by imposing external loads. Research informs us that isometric tensions can have positive effects on muscle fibre recruitment and tendon function. By using bracing and anchoring formats, the benefits of isometric tension can be applied to a range of motion. I call these exercises “polymetric” for the multi-dimensional tensions being used through a range of motion.

Anyone who has used a tool like a wrench on a stubborn nut or bolt knows that bracing the body from the anchored feet on up through the torso and shoulders will produce far greater force than not anchoring and using only the arm. That same wrench situation suggests that the hips and core are furiously working as the bracing link between the feet and hands. Throwing and racquet sports use that same anchor-brace idea in a finger snap of time. Applying the same principles to lunges and split squats provides far more benefit than simply moving up and down. What an athlete can do is add agonist-antagonist tension, a great deal of tension towards max, by squeezing or pushing against those anchors with the big movers of the hips and legs (think ham-glute against iliopsoas-rec femoris).

Polymetric work is hard work!

Anchoring a split squat posture and adding 80% (or more) squeeze-push tension challenges the stability networks to work at much higher intensities alongside the chains establishing the pose. Because of the narrow base of support, the lateral stabilizers of the feet, legs, and spine all need to coordinate how they operate to prevent sway and shudder. As the central movement chains and synergists flex and extend against resistance, stabilizers are co-contracting to keep the joint systems in alignment.

These stabilizers learn to “pre-flex” before transitions to reduce muscle slack and retain those capabilities and sensations as “preparation to move” shifts to higher forces and velocities.3 The beauty of this arrangement is that the whole action becomes self-regulating. If there is an area or particular set of stabilizers that are not functioning in alignment, not at the same tension levels, or fatigue more quickly, then wobbles or disruptions will attract attention and can be remedied.

The ankle, for example, is a frequent “weak spot” in anchoring tension exercises due to injury, faulty movement patterns, and imbalanced development. The larger muscle systems above it simply overwhelm the lower leg stirrups and anchoring muscles of the foot. Some remedial pre-preparation work may be required, as with injury patterns, but for most athletes a shift in focus to the ankles and feet while performing the whole action will be enough to initiate change. The observation of a wobble during an anchored lunge will be the same or similar with the performance skill—the difference is that imbalances may be hidden due to the speed of motion or because we are not sure what to look for or we have learned to effectively mask the faulty pattern. In slower, high tension activity, every imbalance shows itself.

Three Pathways

Working backwards from the hundreds of dynamic landings and plyometrics that challenge force-velocity capabilities, the “preparation to move” selections ensure that the systems that are providing most of the power in landing and takeoff skills are not having to compensate for relatively weaker or imbalanced mobility-stability networks. From this perspective, mobility and stability are on a continuum where we can slide along an axis to find out what works for us.

Mobility and stability are on a continuum where we can slide along an axis to find out what works for us. Share on XAs I found when exploring the hybrid lunge, many variations and postures can be created out of one exercise. The key is in finding variants that suit the needs of the athlete, coupled with the challenges of the target skills. The three pathways outlined here are starting points I suggest with athletes so that their needs are addressed and “cookie-cutter” approaches are avoided. It’s a bit of a Goldilocks process of finding the conditioning and preparation directions that are “just right.”

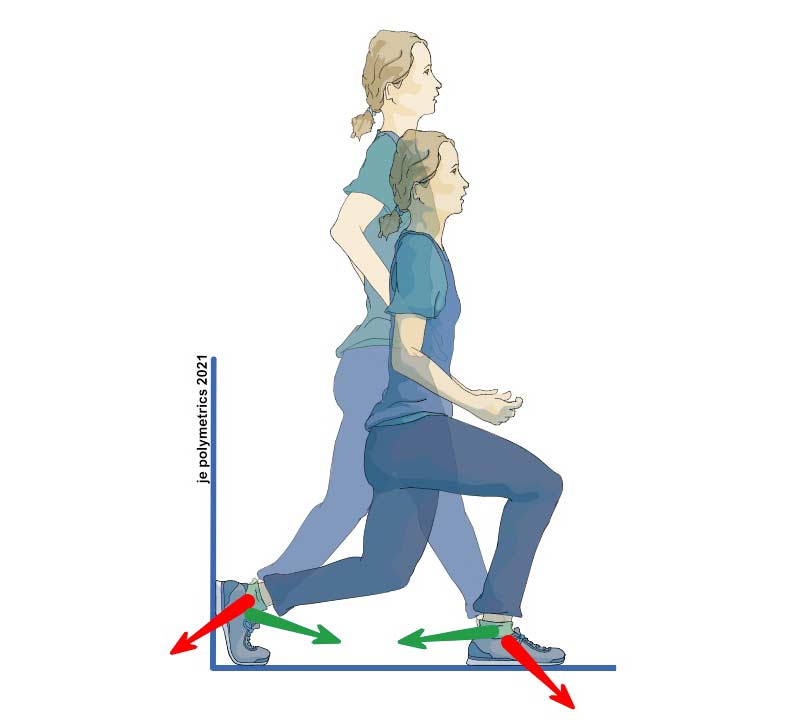

The profiled exercise is an adaptation of a split squat that capitalizes on anchoring and bracing polymetrics to produce great forces while requiring attention to stability. The exercise is called a Watson Squat (with a nod to Matt Watson of Plus Plyos, who provided great feedback in the development of anchored exercising). This split squat has the rear foot positioned up the wall about 30-45 cm (12-18 inches). Because there is a baseline pressure required to hold the position while moving, there are stability networks and mobility chains that never rest. Additionally, pressure against the anchors can be ramped up to near max as extensors and flexors work against each other.

1. Mobility-Stability Combo

The middle of the mobility-stability axis tends to be suited to athletes needing to correct imbalances that are limiting development. We all have imbalances: left-right, top-bottom, front-back, and joint-specific. What we can do is minimize their impact on force-velocity development by enhancing mobility (strength through a range of motion) along with stability at each point along that range. Athletes can select a few key exercises and work them at high intensities to challenge both mobility and stability to remedy imbalances. This strategy also keeps the reps manageable and the focus on consistency.

Video 3. Matt Watson demonstrates “The Watson Squat.”

The Watson Squat works well here as the athlete learns to move through a range of extension and flexion with push actions for both up and down motions. Maintaining stability and knee alignment with the front foot is usually an initial challenge that is remedied within 8-10 sessions due to neuromuscular factors developing in tandem with the mechanics. A typical set structure will be 8-12 reps at about 70% max voluntary intensity that shifts to 5-8 reps with 80%+ intensity.

Maintaining stability and knee alignment with the front foot is usually an initial challenge. Share on X2. More Stability

Through exploration or observation—as with myself not being able to hold a posture—athletes may find that stability is a key limitation. This involves mobility issues, but often needs added neuromuscular emphasis. Smaller tendomuscular groups involved in stability networks often gang together to form strong blocks of tension, as happens with the intrinsic muscles of the feet. This capability needs to be trained and then refined for capacity so that the larger chains do not overwhelm the stabilizing effect that is part of consistency.

Using the Twist Watson Squat introduces the need for constant stabilizing adjustments. In this variant, the tension through the anchors remains much the same, usually at about 60-70% voluntary max to begin with. The torso twists create challenges to the feet, legs, and hips. The lumbar-ham-glute connection is also getting more attention due to the postural tilt.

3. More Mobility

Situations where there is a strength imbalance between the big movers and the stability networks are quite common. A traditional approach is to isolate groups or regions for designated work. The focused emphasis is useful, if not necessary, for rehab and restoration following injury. The limitations are longer-term carryover and time. With areas like ankles or knees, where ligament laxity may require supportive tendomuscular work, ongoing pre-preparation is warranted.

Situations where there is a strength imbalance between the big movers and the stability networks are quite common. Share on X“Preparation to move” domains employ more integrative whole-body work so that areas like the hips and core are also involved. As with the original story, the ankles can be a direct issue, but if the hip abductors and rotators are weakened, they will not offer full support during dynamic skills. Doing some anchor-brace work can be of huge benefit in this instance, as reps and intensities can be applied for max benefits.

One variation of the Watson Squat that works well is to lower the rear leg to the corner of the wall. A Corner-Braced Watson Squat changes dynamic posture slightly, but also allows for both squeeze and push intensities to be applied. Adding capacity to capability at high intensities challenges the various movers and stabilizers to adapt and to recruit muscle fibres to a higher degree. The other advantage of the corner brace variation is that the rhythm is more easily changed from slow-mo to fast without altering the basic mechanics. The stability networks also learn to deal with quicker transitions: a bridge towards more dynamic work that refines how faster eccentric loading is managed.

Takeaways From Then and Now

The original storyline offered a glimpse at how stepping away from the workout format to correct imbalances and restore function was a rudimentary step toward preparation for the training system that was to fuel performance. Without that effort, the performance ceiling would remain simply because historical constraints were carried forwards into the training formats. Interventions with mobility and stability work altered how the body responded to movements, balanced strength deficits, and created new patterns allowing skill development with joint protection.

That story began with the reflection that a valuable lesson was learned; and, in fact, there were more than one. One important insight was an awareness of body plasticity: the ability to modify how the body responds and adapts. Most of us, if asked, believe that a great deal of “who we are” is genetically set, and relatedly, that talent is for the few. Plasticity shows us that most of who we are can be modified and adapted to a variety of demands…that’s what training does.

The overlapping lesson was one of self-responsibility. Taking charge and owning the directions for growth is something we can embrace at all ages. Sport development, as with other cultural expressions, is a great place to form and refine this quality. The opposite of self-responsibility is not irresponsibility as you may think: it’s dependency. Although the original story had youthful flaws in terms of communication, it was also an exercise in self-responsibility. David Hemery, the 1968 gold medallist in 400m hurdles, pointed out in his survey of world-class performers that controlling your own destiny is a shared trait.4 The alternative is to show up and let things happen, or to expect a program to magically transform “here” into “there.”

Taking charge and owning the directions for growth is something we can embrace at all ages. Share on XFinally, it needs to be said that lunges and split squats were not some special or secret remedy for breaking through a performance ceiling. As noted, the clues to why the limitations existed were more obvious in slower activities. It is not the exercise providing the answers, it is the sensory information we get from the exercise that creates a decision-remedy pathway. Our bodies are laced with sensors telling us where we are and how well we move. Learning to listen to our bodily information, processing it, and deciding how to proceed is the biggest lesson of all; and it is something we can carry from “here” to “there.”

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References & Additional Reading

1. De Mers, M.S., Hicks, J.L, and Delp, S.L. Preparatory Co-Activation of the Ankle Muscles May Prevent Ankle Inversion Injuries. Journal of Biomechanics. 2017;52:17-23.

2. Bosch, F. Anatomy of Agility: Movement Analysis in Sport. 20/10 Publishers. 2020.

3. Van Hooren, B. and Bosch, F. Influence of Muscle Slack on High Intensity Sport Performance: A Review. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2016;38(5):75-87.

4. Hemery, D. Sporting Excellence: What Makes a Champion? Harper Collins. 1991.