In the sport performance world, motivation is an essential part of achievement. Sport psychology and motivation strategies seem to be continuously growing in popularity. Consider, for example, the fact that Seattle Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson has hired a personal “mental coach”—this coach helps him with a wide variety of performance issues, whether it be how to realign focus after a bad quarter or steering him away from music that may negatively affect his mental state.

There are numerous books, articles, podcasts, and YouTube videos on how to integrate principles of sport psychology into sport performance practices. The focus of these resources is primarily on coaching principles, such as Conscious Coaching by Brett Bartholomew1, to name just one. Oftentimes, these sources discuss how to effectively communicate with our athletes (both verbally and nonverbally). They have proven to be valuable contributions to the field and have changed the way many professionals interact with their athletes. With that being said, strength and conditioning coaches, physiotherapists, athletic trainers, and dietitians may benefit from using principles of sport psychology not only in their communication, but in their strategy design as well.

By using the Self-Determination Theory in my program design, the athletes I work with progress through movement patterns faster and report finding more enjoyment in the training process. Share on XBy using the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) in my program design, the athletes I work with have progressed through movement patterns faster and reported finding more enjoyment in the training process. Additionally, there are higher levels of training adherence during times when personal interaction is scarce. This article will discuss the SDT and how sport performance coaches may incorporate its fundamental principles into their prescribed training periodization plan in order to maximize athlete motivation.

Self-Determination Theory

The Self-Determination Theory is a theory of motivation. It breaks motivation down into three separate categories:

-

- Autonomous Motivation. Comprises both intrinsic motivation and the types of extrinsic motivation in which people have identified with an activity’s value and ideally will have integrated it into their sense of self.2

-

- Controlled Motivation. Consists of both external regulation, in which one’s behavior is a function of external contingencies of reward or punishment, and introjected regulation, in which the regulation of action has been partially internalized and is energized by factors such as an approval motive, avoidance of shame, contingent self-esteem, and ego involvements.2

-

- Amotivation. Otherwise known as unwillingness2. If you look up some definitions via Google, you will find some interesting ones out there, but the authors who are credited with bringing the theory to popularity keep it simple.

We know that autonomous motivation and controlled motivation lead to very different outcomes, with autonomous motivation yielding greater psychological health, more effective performance, and greater long-term persistence2. This information is seemingly of no surprise—in our profession, the ideas of intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation have been commonly known for some time now.

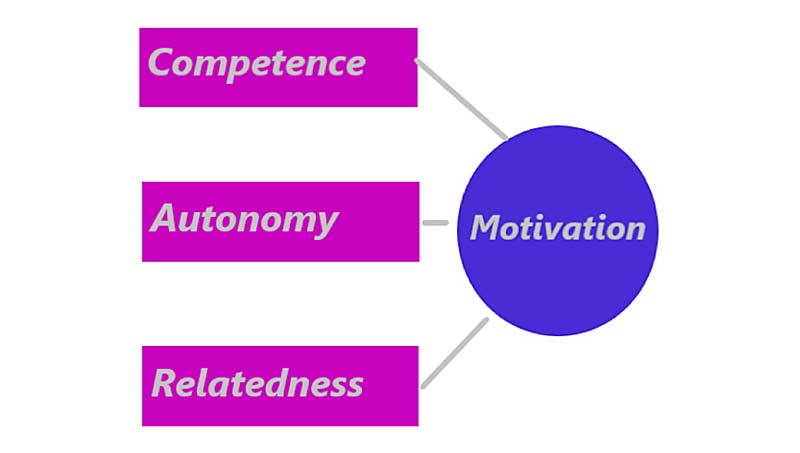

The focus of this article will be on the autonomous motivation section of the SDT. Research suggests that if an individual is to experience high levels of autonomous motivation, they must have three basic psychological needs met: competence, autonomy, and relatedness.2 While the most recent research has broken down these needs even further—adding complexities and analyzing specific situations of social context, mindfulness, energy, and vitality—I will adopt a “bird’s-eye” view to ensure brevity and practicality.

Competence

Competence is known as the ability to do something successfully or efficiently. Therefore, it is task specific. It is important to note that feelings of competence may differ many times within a training or practice session.

Let us consider a collegiate men’s lacrosse defender. In men’s lacrosse, a defender uses an implement with a longer shaft than his teammates (midfielders, attackmen, faceoff, and goalies) and typically stays on one half of the field the entire game. A defender may feel confident with passing, cradling, and checks on their half of the field, but as soon as they cross to the attacking side of the field that athlete may immediately lose a sense of competence, because they rarely find themselves there. According to the SDT, if that athlete continually feels that lack of competence, they are much less likely to ever go on the attacking half of the field. This lack of competence has the power to have major negative effects on the athlete’s performance, such as hesitation during play, unforced turnovers, etc.

As sport performance coaches, we press our athletes to improve at certain tasks on a daily basis. In order to maximize our athletes’ motivation, we must maximize their feeling of competence; but in order to improve at a task, an individual must be challenged and experience a sense of struggle3. This situation illustrates the importance of incorporating a proper progression model when developing a training plan. Maximizing motivation is just as important as maximizing physiological responses to training, because we know that consistency is the most important variable in physical development4.

Progression models will likely look different between sport performance coaches. We all have different opinions and experiences that drive our training philosophy; that is one of the beauties of our profession. With that being said, coaches who apply SDT consider the psychological outcomes they hope to produce in a session and plan their progressions accordingly. Athletes should leave the sessions feeling challenged, but also feeling the reward of successfully overcoming a challenge.

Athletes should leave training sessions feeling challenged, but also feeling the reward of successfully overcoming a challenge. This can maximize motivation. Share on XStarting with fundamental movement patterns the athlete can successfully complete—while adding strain through tempo and/or volume—is a great way to maximize the feeling of competence. If the athlete continually performs complex tasks with little to no success throughout the entire session, that athlete is not likely to stay motivated very long.

Coaches may consider these things when designing programs in order to maximize the feeling of competence:

-

- Incorporating a segment within a training session that is simple, so that the athlete may give full effort (i.e., “Finishers”).

-

- Using single-joint exercises within a session.

-

- Starting with the most complex movements and finishing with the simplest within a training session.

-

- Individualizing programs based off the athlete’s abilities.

-

- Use the sandwich approach:

-

- Movement 1: Something relatively non-fatiguing that the athlete is highly capable with (i.e., dribbling).

- Movement 2: Something the athlete struggles with (i.e., a specific weakness).

- Movement 3: Something fatiguing and simple (i.e., bike sprints).

Incorporating any of these strategies may enhance your athlete’s feeling of competence. Assuming the other two basic needs of motivation are met (which we are about to discuss), these strategies will likely enhance your athlete’s motivation and maximize the sustainability of it as well.

Autonomy

Autonomy is known as the right or condition of self-government. Oftentimes, academic authors from an array of disciplines tend to have slightly varied interpretations of the term in accordance with their professional discipline. In general, almost all of the interpretations refer back to the ability of choice. In order for autonomy to exist, one must have the ability to choose.

This idea of choice is a significant consideration for sport performance coaches. The athletes we work with have most of their day scheduled for them: They are told when they have film study, practice, meals, rehabilitation, aerobic conditioning, strength training, etc. Many organizations go so far as to tell the athletes when they need to be in bed. All of these things have a positive impact on the athlete’s performance, and they are all important. The complication arises, however, when the athlete doesn’t have a choice in the matter. According to the SDT, when someone is not given the freedom of choice, motivation is diminished.5

As sport performance coaches, there is not much we can do about the density of our athletes’ schedules. Oftentimes, we cannot even manipulate the schedule of our athletes’ strength and conditioning training—but we can consider the lack of autonomy in their scheduling process when we are developing our training sessions.

In order for autonomy to exist, one must have the ability to choose. In our training designs, we may consider developing segments within a session in which the athlete has a choice. Share on XIn our training designs, we may consider developing segments within a session in which the athlete has a choice. These choices may be a different movement, loading structure, exercise order, physiological emphasis, etc. It is imperative that the coach have the choices available from the start of the session or training block. If an athlete has to go up to the coach and request an alternate, it no longer feels like a choice for that athlete but more like a modification. When athletes request a modification, it is often because of something negative (i.e., pain, fatigue, etc.). Consequently, when performing the alternative, it may not have as positive an impact as if the modification were already given as an option.

Coaches may consider these things when designing programs in order to maximize the feeling of autonomy:

-

- Allow athletes to design their own workouts on occasion.

-

- Consistently have alternate exercises available (and not based on injury).

-

- Use RPEs as a volume and intensity structure.

-

- Allow athletes to create and lead warm-ups on occasion.

-

- Have optional and alternate training days available consistently.

-

- Have alternate implements available consistently.

-

- Have optional loading schemes available consistently (8×3 instead of 3×8).

Having optional training days and using athlete-led warm-ups are my two go-tos in regard to autonomy. What I like about both strategies is that they require a sense of accountability. For the warm-ups, the athlete must prepare and spend time thinking about the process; meanwhile, having alternate training days requires athletes to consider their schedules and make time commitments accordingly. Both situations have positive implications outside of sport as well.

Assuming a coach has already accounted for the sense of competence in their programming, addressing these considerations will bring us one step closer to a thoroughly motivated athlete, and hopefully a more responsible one as well!

Relatedness

Relatedness is known as the state or fact of being related or connected. This is the emphasis that most of our current sport psychology resources (those relevant to sport performance coaching) have focused on. There is a plethora of information online that illustrates how a coach may learn to better relate to their athletes. As mentioned previously, the feeling of relatedness tends to develop within one’s interactions with their athletes: showing you care about them as a person, asking about their lives outside of sport, learning what type of feedback they best respond to, giving them a bit of insight into who you are as a person outside of work, etc.

While there is no replacing the effects or importance of how a coach interacts with their athletes, relatedness can be addressed within the program design process as well. Programming movements that you can skillfully demonstrate is an undervalued part of the program design process. For instance, I separated my shoulder back in the day while playing rugby, which limits my ability to demonstrate any overhead pressing movement.

Programming movements that you (the coach) can skillfully demonstrate is an undervalued part of the program design process, and it can lead to positive feelings of relatedness. Share on XAs a young coach, I did not consider this when I was programming; then, when it came time to teach the movement, I blew it! My technique was awful, and I could feel it. I tried to verbally communicate proper technique after my poor demonstration, but it didn’t work too well. Throughout the whole day I had multiple athletes use poor technique, and some even cracked some jokes about how my demonstration looked. The jokes were well-intentioned and lighthearted, but I’d be a fool to think there weren’t some underlying negative effects due to my poor demonstration.

Now let’s consider a different situation; one in which I felt like a much more competent coach. I have always been capable when it comes to any pulling exercise. During an evening training session my athletes were performing deadlifts as the primary movement, and we had a group of them making the same mistake during their initial setup position. I decided to pause the lift and give the entire team a couple of coaching cues, and while doing so, I happened to be demonstrating on the platform of our strongest group of guys. After giving the cues, the guys started probing me to see if I could move the weight that was on the bar, so I decided to do so…10 times! Everyone started yelling and smiling and cheering, which made for a fun and energetic training session.

While this scenario sounds cheesy (and it is), it also demonstrates the positive implications of relatedness. The athletes’ opinions and efforts completely changed based solely on my ability to personally do what I asked of them. An athlete connects to their sport performance coach through the avenue of fitness—when a coach is unable to exude some basic attributes of the underlying avenue of connection, it hurts the connection. When designing a training block, a coach should consider their ability to demonstrate a skill or movement effectively throughout a session.

Supplementary training sessions in which a coach can engage in competition with their athletes create an immediate sense of relatedness. Athletes and coaches get to communicate in a less formal and more peer-like manner. In my experience, flag football, basketball, and medicine ball volleyball are all great options. When competing alongside your athletes, be sure to keep it professional.

Coaches may consider these things when designing programs in order to maximize the feeling of relatedness:

-

- Maintain personal fitness levels and/or goals.

-

- Schedule sessions in which the sport performance coach may compete with their athletes.

-

- Talk about topics of interest outside of sport.

-

- Make time to engage in one-on-one interaction.

Incorporating SDT in Your Own Way

We now know that in order for someone to have high levels of autonomous motivation, three psychological needs must be met: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. We have also discussed some strategies that coaches may use to incorporate SDT into their own practice. When considering how to apply SDT, it is important to make sure it is unique to your coaching style and philosophy. The more individualized and unique the approach, the more success you will have.

When considering how to apply Self-Determination Theory, make sure it is unique to your coaching style and philosophy. The more individualized the approach, the more success you will have. Share on XI use proper progression models to address competence, because it is clear to both me and the athlete what they need to do in order to make it to the next step—there is nothing subjective about it. I use optional training days and athlete-led warm-ups to address autonomy, because they require personal commitment and effort on the athlete’s end. I maintain my own fitness levels and compete alongside my athletes whenever I can to address relatedness. These strategies align with who I am and what I believe in. I have also tried and failed at implementing other strategies plenty of times before settling on these ones.

According to my athletes, the strategies above have had an impact. Whenever I traveled with the team, an athlete and I always seemed to be reminiscing about a memory we had during a workout or competition. The athletes reported truly enjoying the training process, and consistently demonstrated commitment by showing up in the fall ready to train.

I’m sure you can come up with some objective ways to measure the effects of incorporating SDT, but my recommendation is just to ask your athletes. Engage with them, be creative, try new things, be open-minded, ask for feedback from coaches and administration, and have fun doing it!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Bartholomew, B. Conscious Coaching: The Art and Science of Building Buy-In. 2017. Omaha, NE: Bartholomew Strength.

2. Deci, E. L. and Ryan, R. M. “Self-Determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health.” Canadian Psychology. 2008; 49(3): 182-185.

3. Dreyfus, S. E. “The Five-Stage Model of Adult Skill Acquisition.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 2004; 24(3): 177-181.

4. Chiu, L. Z. and Bradford, J. L. “The Fitness-Fatigue Model Revisited: Implications for Planning Short- and Long-Term Training.” Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2003; 25(6): 42-51.

5. Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. “Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being.” American Psychologist. 2000; 55(1): 68-78.