About 20 years ago, a high school coach gave me a tour of his athletic facilities. We stopped by the weight room and saw a young man squatting, all the way down and without knee wraps, 415 pounds for five reps. When the coach asked what position he played on the football team, the young giant replied, “I don’t play football—I just like to squat!”

I eventually became a volunteer strength coach at that school, teaching a girls PE elective with athletes and non-athletes. After a few semesters, 12 girls cleaned 135 pounds (five over 150), and nine vertical jumped (no step) at least 23 inches. Although the athletes were impressive, many non-athletes demonstrated remarkable strength and jumping ability.

The point of these examples is that many males and females with exceptional athletic talent never play sports in high school. As for numbers, the Youth Sports Institute at Michigan State University estimates that 70% of kids quit organized sports by age 13. This means sports coaches in high school only have access to about 30% of their athletic talent pool. Think about this.

School districts separate schools into divisions based on the number of students. A school with 2,000 students will compete against schools with approximately 2,000 students, and a school with 1,000 students will compete against schools with about 1,000 students.

What if coaches who work in a school with 1,000 students could tap into another 10%, 15%, or 20% of its student population to try out for sports? It’s worth considering the advantages. Share on XWhat if coaches who work in a school with 1,000 students could tap into another 10%, 15%, or 20% of its student population to try out for sports? That would significantly increase their athletic talent pool. Another 30% would double it, potentially putting them on equal footing with schools with twice their enrollment. Although it’s unrealistic to achieve 100% participation, it’s worth considering the advantages of expanding a school’s athletic talent pool.

This begs the question, “Why do so many kids give up on athletics before high school?”

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=14417]

The Fun Factor

A Minnesota Amateur Sports Commission study asked kids about their experiences with coaches. Here’s what the researchers found:

- 45.3% were called names, yelled at, or insulted by coaches.

- 21% were pressured to play with an injury.

- 17.5% were hit, kicked, or slapped.

With these red flags, it’s no surprise that one of the primary answers kids give for quitting sports is that they “are not having fun.”

Besides these coaching abuses, I would add to the list the coaches who discourage less-talented athletes from staying in the game. Let me expand on this point.

Several years ago, track and field athletes from one high school told me their head coach only paid attention to those who could score team points. Winning was top of mind, and he had no desire to spend his time or resources helping less-gifted athletes reach their potential.

Because this coach only wanted to work with the best athletes, he tried recruiting athletes away from other sports and encouraged his athletes to participate in indoor and outdoor track. This tactic backfired.

The year after he was hired, only one athlete on the football team went out for track. After two years, his track team went from state championship contenders to cellar dwellers. He would not coach a third season.

Yes, the football players could have benefited from participating in track in the outdoor season. However, the coaches didn’t want to risk losing their athletes, particularly because this track coach encouraged his athletes to compete in the indoor and outdoor seasons. (I’ve seen this conflict with weightlifting coaches. A weightlifting colleague of mine was coaching weight training at a high school. One of the best football players quit the team to focus on weightlifting year-round with my friend, and the athlete went on to compete internationally. However, the head football coach feared losing more athletes, so my friend was no longer allowed to work with football players.)

It’s a shame that so many athletes dealt with this track and field coach for so long, and a more extensive screening process may have prevented this problem. In fact, this coach had “allegedly” been pressured to resign from his previous coaching position in another state due to complaints from parents about his behavior. I understand this information was never passed on to the school administration because of privacy laws. So, what can be done?

A Question of Character

Although background checks are essential, they’re just one aspect of the hiring process. “What a background check does is show what kind of legal action has been taken against a person,” says sports liability consultant Dr. Marc Rabinoff. “If they’ve had a felony conviction, even if it was 20 years ago, and they’ve paid their debt to society, it would show up.” That’s the plus side.

The downside is that background checks are generally performed only once every two years. The process doesn’t include regularly checking someone’s criminal history and reporting new illegal activities to the hiring organization. “What happens when a coach comes through squeaky clean in a background check but gets convicted of a sex crime involving a minor a month after you’ve completed the background check? You will have to wait 23 months until the next background check is performed to hear about it,” says Rabinoff.

Rabinoff says employers must call references when hiring coaches, even volunteer coaches, and “ask the hard questions so you get a good grasp of an individual’s character.” He also recommends that incoming coaches be made aware of the expected behavior standards and sign a document stating they agree to them. For reference, Rabinoff says USA Soccer has developed documents that schools and sports organizations can use as templates. And there’s much more that can be done.

Bigger Faster Stronger (BFS) has conducted high school and middle school character education clinics for over four decades, often giving hundreds of presentations a year. Their instructors are primarily certified teachers and accomplished coaches. These four-hour clinics are called Be an 11, and their motto is “On a scale of 1 to 10, be an 11!”

The BFS clinics are designed to help athletes set worthy goals in all areas of life, determine the steps to achieve those goals, and be able to tell right from wrong. Another benefit is that they help athletes become role models that their peers would admire. What’s unique is that the clinics involve athletes, parents, and coaches—BFS wants everyone to be on the same page as to what’s expected of them.

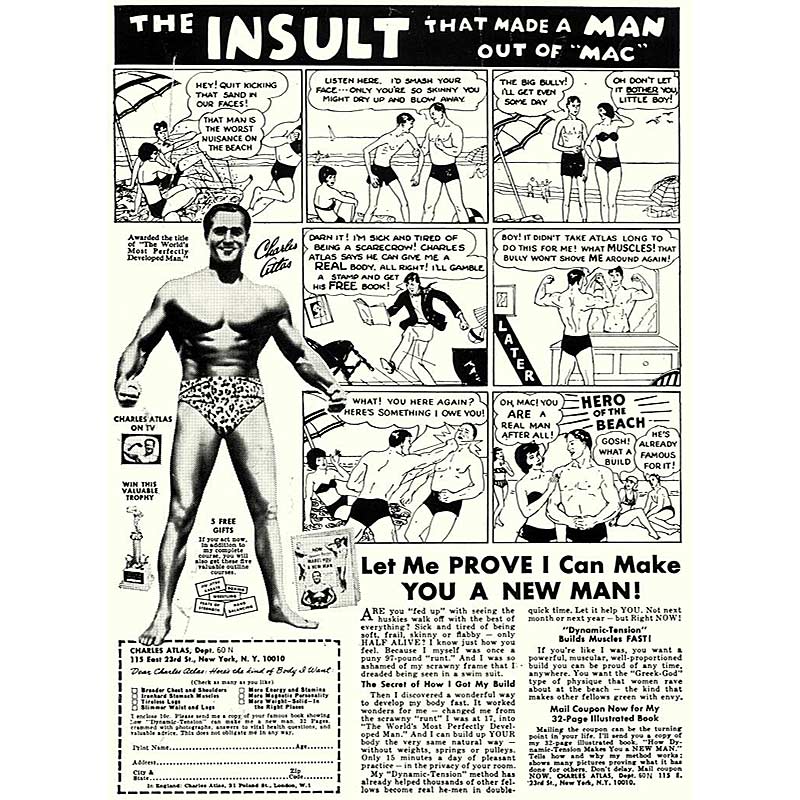

Remember the Charles Atlas ads with a strong, muscular bully kicking sand in the face of a wimpy guy in front of his girlfriend? A “Be an 11” athlete would pull that bully aside and try to turn him into the type of person who might even encourage the skinny guy to train with him to build up his body and self-confidence.

Why focus on athletes rather than the general student body? One reason is that athletes are often admired and respected among their peers, often more than teachers. As the editor of their magazine, BFS, I interviewed hundreds of coaches and school administrators over two decades. Coaches often told me that when athletes become role models, there’s a trickle-down effect of positive behavior throughout the school.

Many other organizations offer character education workshops, each with its unique approach to helping kids. These may help prevent coaching abuses, create a supportive environment for kids to continue playing sports, and encourage some of the Forgotten 70 Percent to try out for a team.

Those are some of the social and psychological reasons why kids quit sports. Now, let’s look at some of the physical reasons.

Bigger, Faster, Older!

If you fill a room with 12-year-olds, some will have the physical maturity of an 11-year-old and some that of a 13- or 14-year-old. Therefore, from a physical perspective, a sports program with 12-year-olds could have a mix of 11-year-olds competing against 14-year-olds. Such an environment is not much fun for those less physically mature (“Ant, meet boot!”), and these weaker kids often quit.

A year can make a big difference in physical maturity. Although rare, I’ve heard of parents of football players holding back their sons a year in school so they will be older than their classmates. The extra year enabled them to become bigger and stronger than their teammates during their junior and senior years when the college scouts started paying attention. Consider the practice of redshirting.

College football teams often redshirt players to give them an extra year to improve their strength, power, and quickness. At Brigham Young University, a type of extended redshirting occurs because many linemen pause their education to go on a two-year mission for the Mormon Church. They can still lift during this period, packing on slabs of muscle mass to give them an edge on the gridiron. (When I coached at the Air Force Academy, I recall that the BYU offensive linemen were so physically imposing they could be classified as a different species!)

The bottom line is that coaches need to recognize that kids physically mature at different rates. Don’t rush nature; instead, encourage these young men and women to stay with the program. Your patience may pay off with big returns.

The bottom line is that coaches need to recognize that kids physically mature at different rates. Don’t rush nature; instead, encourage these young men and women to stay with the program. Share on X

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=14422]

The Training Edge

Besides chronological age, another factor to consider is an athlete’s training age, which refers to how long an athlete has been involved in a sport or physical training. I recently interviewed Ciro Ibañez, a 1983 Pan American champion in weightlifting who runs the Beyond Lifting Club in Montreal, Canada. His wife, Abigail Guerrero, coaches their daughter, Emily Ibañez Guerrero. Emily fulfills the definition of an outlier.

When she was six, Emily began extensive physical training, which included gymnastics and plyometrics. About 18 months later, she started lifting weights, focusing on technique. She is now 12 and therefore has a training age of six years. The result? Weighing 121 pounds, she clean and jerked 231 pounds and back squatted 319 pounds! Again, she’s 12.

Video 1: Emily Ibañez Guerrero fulfills the definition of an “outlier.” Just 12 years old and weighing 121 pounds, here she clean and jerks 231 pounds and squats 319 pounds!

While early sports specialization is often necessary to compete at the highest levels, it has drawbacks. Besides mental burnout, the risk of injury may be higher, resulting in athletes quitting their sport. For example, one study on 1,544 high school athletes found that those who played only one sport had an 85% higher incidence of lower-extremity injury. That’s the bad news.

The good news is that supplementary weight training significantly reduces overuse injuries and total injuries for athletes specializing in one sport. This is my approach with my golfer, Ava Andoscia.

As a high school freshman, Andoscia was the only girl to earn a spot on the varsity golf team and made the Providence Journal All-State Team. In practice, she has scored 76 on 18 holes and has a best long drive of 275 yards. Because she plays golf year-round, I give her specific exercises to prevent muscle imbalances.

Injury prevention is one thing, but what about injured athletes forced to take extended breaks from sports? Being out of the game too long may cause athletes to quit, thinking they might be unable to return to their previous level. Again, the weight room offers an answer.

The Art of the Comeback

Let’s say a high school football player has to quit the team during their freshman year due to a serious injury, then decides to rejoin the team in their junior year. Wouldn’t you think that young man might have a better shot of seeing playing time if he’d been lifting hard and packing on muscle?

When an athlete suffers a serious injury, such as an ACL tear or an Achilles rupture, they can still get involved in an aggressive weight training program. If an athlete injures their knees, train the upper body. If they injure their shoulders, train the lower body. Legendary Bulgarian weightlifting coach Ivan Abadjiev said if an athlete is injured so severely that they can only lift a finger, “They should go to the gym and lift a finger!”

With the right encouragement and a sound rehab program, injured athletes may return to their sport stronger than ever. This was the case with two of my track and field athletes at Brown University, Maddie Frey and Bretram Rogers. Both mastered the art of the comeback.

Frey was a high school soccer player who tore her ACL. After a long rehab process, she switched to track and field as the risk of reinjuring her knee was lower—she even competed in cross country. In 2020, she broke the 32-year-old record in the 200m at Brown. Likewise, in his senior year in high school, Rogers severely tore his hamstring, causing nerve damage. He broke Brown’s indoor 60m hurdles record set in 1959 and the 110m hurdles record set in 2007.

Of course, for athletes to come back from serious injuries quickly requires good training facilities. Machines often come in handy, particularly with athletes who have injuries requiring a limb to be immobilized. This brings us to the issue of athletic training facilities.

United We Stand!

One of the realities of coaching at the high school level is budget restrictions, particularly for weight rooms. Promoting a unified weight training program that involves all students, not just athletes, increases a coach’s resources.

A reality of coaching at the high school level is budget restrictions. Promoting a unified weight training program that involves all students, not just athletes, increases a coach’s resources. Share on XIn many schools, the athletic and physical education departments have separate budgets. At the high school where I coached in Utah, the weight room for athletes consisted primarily of benches, squat racks, and barbells and dumbbells that had seen better days.

At this same school, the weight room reserved for the physical education department received a grant to develop a large circuit of resistance training and cardio machines that probably ran north of $25,000. I saw the same situation in a nearby school with two weight rooms working with separate budgets—the cardio equipment alone in the PE room retailed for at least $20,000.

Why separate PE and athletic department weight rooms? How about pooling resources to make one master weight room benefitting both programs? Athletes could use the machines for rehabilitation and more sport-specific exercises. PE students could be introduced to dynamic free-weight exercises (such as cleans) and plyometrics to make them better physically prepared if they try out for a sport. Also, having athletes and non-athletes train together may help break down social barriers and thus encourage more of the general student population to give organized sports another go.

Having athletes and non-athletes train together may help break down social barriers and thus encourage more of the general student population to give organized sports another go. Share on X“We don’t have the physical requirements for physical education that we had 30 years ago,” says Bob Rowbotham, CEO of BFS. “Based upon our experience, when the weight room is set up correctly, weight training becomes one of the most popular classes in the PE curriculum.” (By the way, my high school girls’ weight training class was an elective, and it grew from 20 students to 92 after a few semesters.)

One recruiting idea to take into the Forgotten 70 Percent is to consider having students from feeder schools participate in your summer weight training classes before high school.

Inviting feeder school athletes into a high school summer program reduces the amount of teaching required when an athlete enters high school. It also creates a safer training environment. These athletes will know how to perform the exercises, spot, read workouts, and behave in a weight room. It may even keep a few middle school athletes from dropping out of sports, as they will be exposed to the high school sports experience.

One coach who benefitted from this approach is Head Football Coach Matt Biehler at Conway Springs High School in Conway, Kansas. I wrote an article about Biehler’s program about a dozen years ago, and he noted that his feeder program helped avoid the hazing and bullying problems many schools face as the older players “take the younger players under their wing.”

Another option for weight training is to bring in the private sector. From 2015 to 2020, I coached over 150 athletes from 20 middle and high schools in three private gyms. The sports coaches loved this program as it allowed them to focus on their other responsibilities rather than spending several hours a week in the weight room. My program is not unique.

In Rhode Island, one personal trainer opened a 4,500-square-foot strength and conditioning facility in a warehouse about a half mile from a large high school near me. Brilliant!

Kids could receive high-level coaching and train with their teammates at a discounted rate. School administrators loved it, as they didn’t have to invest in upgrading their weight room or foot the expense of having staff coach all the kids who wanted to train. As a bonus, the gym was a great marketing tool for their personal training business for adults, such that the parents of the athletes would train during the early hours while their kids were in school.

If your goal is to win and expose more athletes to the joys of sports, consider these ideas to increase your talent pool by tapping into the Forgotten 70 Percent!

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11153]

Summary

- Seventy percent of kids quit organized sports by the age of 13.

- One of the primary reasons kids quit sports is that it’s no longer fun.

- Abusive behavior by coaches contributes to kids quitting sports.

- Background checks and checking references help ensure more professionalism in coaches.

- Athletes physically mature at different rates.

- Chronological age does not necessarily reflect training age.

- Character education programs can help keep kids interested in sports.

- Weight training can prevent and rehabilitate injuries.

- Weight training enables athletes to return to the game faster and often in better condition.

- Pooling the PE and athletic departments’ resources improves the quality of both programs.

- Having athletes and non-athletes train together may increase the number of students participating in sports.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Goss, Kim. “The Hunter High School Experiment,” Bigger Faster Stronger, January/February 2010, pp 18–21.

O’Sullivan, John. “Why Kids Quit Sports,” Changing the Game Project, May 5, 2015.

Lench, Brooke De. “Abuse in Youth Sports Takes Many Different Forms,” Momsteam, June 21, 2018.

Minnesota Amateur Sports Commission, “Troubling Signals from Youth Sports,” Organized Youth Sports Today, 1993.

Rabinoff, Marc. “The Truth About Background Checks,” Bigger Faster Stronger, September/October 2010, pp 46–48.

Ibañez, Ciro. Personal Communication, September 26, 2023.

Goss, Kim. “Conway Springs High: Training with the Best,” Bigger Faster Stronger, July/August 2012, pp 14–16.