Injury prevention programs (IPPs) have been shown to be effective at reducing the risk of injury. The 11+, for example, has been shown to reduce hamstring injuries by 60%, hip and groin injuries by 41%, knee injuries by 48%, and ankle injuries by 32%. It reduces the risk of all injuries by 39% (Thorborg et al., 2017).

According to Arundale et al., 2023, the components of effective injury risk reduction programs include:

- Implementation at the youth level.

- Beginning in the pre-season and continuing through the regular season.

- Being performed multiple times for an overall time of at least 30 minutes per week.

- Being multifaceted and including a combination of strength and plyometric exercises.

- Having a high level of compliance.

Even the best program in the world won’t work if it doesn’t get done.

Unfortunately, implementing IPPs has proven to be challenging. Barriers to implementation are varied and context-dependent.

In elite women’s footballers from the 2019 FIFA World Cup, players identified player motivation and the attitude of coaches as the primary barriers to implementation (Geertsema et al., 2021). A review of IPPs found that motivation, time requirements, skill requirements for program facilitators, compliance, and cost were all barriers to implementation (Bogardus et al., 2019). In my own experience as a youth soccer coach, a lack of confidence in delivering the program, a lack of field space, and limited time seem to prevent coaches from implementing IPPs.

In my experience as a youth soccer coach, a lack of confidence in delivering the program, little field space, and limited time seem to prevent coaches from implementing IPPs, says @NSurdykaPhysio. Share on XAs physical therapists, athletic trainers, performance coaches, and sport scientists, we have access to scientific knowledge on IPPs. However, we are not always the people best positioned to deliver these programs, especially at the youth level, where it is crucial to begin their implementation. While 59% of physical therapists worldwide are aware of IPPs, only 37% actually implement any in their current practice (Al Attar et al., 2021).

Outside of professional academies, how many of us are ever consistently present at training sessions at the youth level? How many of us have access to youth athletes for the recommended 2–3 times per week? To make the most impact and deliver IPPs to the largest number of athletes possible, it has to come from the people who are actually there with them on a regular basis: their coaches (Bizzini and Dvorak, 2015).

Coaching the Coaches

As we all know, it can take years for scientific knowledge to be translated into practice. However, I believe there are ways that we can begin educating coaches on IPPs. Ideally, youth soccer leagues and national federations would mandate that training on IPPs be part of coaching education courses and a requirement to obtain a coaching license.

Outside of governance and policy at the macro level, healthcare and performance professionals can run off-season or pre-season clinics and symposiums to teach local coaches how to run an IPP with their teams. Instead of focusing community outreach on individual teams or clubs, promote a one-day training course for as many youth coaches as possible. Social media can also be a powerful tool for disseminating information to the general public.

If coaches are to be the primary stakeholders responsible for the delivery of IPPs, then the challenges they face in implementing them need to be addressed. One barrier to IPP implementation by youth coaches is a lack of resources and education on what IPPs are, why they’re important, and how exactly to deliver them. Our role, then, as healthcare and performance professionals, needs to shift away from strictly the delivery of these programs to the education of coaches. If we can effectively educate them to deliver IPPs, then more youth athletes might get access to them. When we educate coaches on IPPs, it’s important to highlight their effectiveness in reducing injury risk to increase motivation and buy-in.

In order to enhance buy-in from coaches, the IPP needs to be easy to integrate into the team’s normal training structure. At the youth level, teams might have access to half a pitch for 60–90 minutes twice per week. Coaches perceive that IPPs take too much time (Minnig et al., 2022) and can feel pressure to jump right into the training session to maximize their time on the pitch. There are a couple of ways that we can address this barrier—perceived or real—and help coaches implement IPPs in their training sessions.

Strategies for Implementing IPPs

In 2019, Whalen et al. found that moving part 2 of the 11+ (strength, plyometrics, and balance exercises) was still effective at reducing injury risk while also improving compliance at the semi-professional level. This might be an effective strategy at the youth level because it reduces the time spent performing the 11+ before starting the training session. Coaches can have the athletes perform part 2 of the 11+ while they are wrapping up the session and summarizing key coaching points. They can also perform this part of the 11+ off to the side of the field so they don’t have to worry about going beyond their allotted time slot or being in the way of another team starting their training session.

Another possible method of addressing this time barrier is to integrate components of an IPP more seamlessly into the session. Most youth soccer training sessions begin with some type of technical warm-up, consisting of anything from passing patterns to dribbling in a grid. Why not try to integrate aspects of an IPP into this technical warm-up that coaches are already doing?

Why not try to integrate aspects of an injury prevention program into the technical warm-up that coaches are already doing? asks @NSurdykaPhysio. Share on XIf the team’s technical warm-up is dribbling inside a 20x20m grid and working on individual skills, you can add in the exercises that are part of the 11+. So instead of having the athletes do the running exercises down a straight line of cones, they simply perform them within the 20×20 grid, mixed in with the technical skills. Below is an example of a dribbling and individual ball control technical warm-up performed with components of an IPP for youth soccer players:

-

- Each player has a soccer ball inside a 20×20 grid.

Instructions: Dribble your soccer balls. The only rules right now are don’t stop moving unless I say “freeze,” don’t bump into anyone, and don’t leave the grid unless I tell you to.

Have them do this for about a minute. Then tell them to freeze to listen to the following instructions: Now, every time I say the number 1, I want you to leave your soccer ball, go find another soccer ball, do 10 toe taps, then go back to your ball and start dribbling again. When I say the number 2, I want you to stop your soccer ball, side shuffle to another soccer ball, box the ball 10 times, then side shuffle back to your soccer ball and dribble again. When I say the number 3, I want you to leave your soccer ball, run as fast as you can outside of the grid, and then run back to your soccer ball as fast as you can and start dribbling again.

In this part of the warm-up, the players are getting additional technical work on the ball and have also been introduced to high knees (via the toe taps), side shuffling, changing direction, and scanning the environment for a free soccer ball. I usually do 3–5 rounds of each number randomly before mixing it up again.

Here’s an example set of instructions for the next round of the warm-up:

Now, every time I say the color purple, I want you to stop your soccer ball, jump over it with both feet together, turn around and jump over it again, and then start dribbling again. When I say yellow, I want you to stand on one leg, hop sideways to land on the other leg, hold it for two seconds, then hop back to the other leg and hold for two seconds, then start dribbling again. When I say green, I want you to do fast feet forward for 10 steps and fast feet backward for 10 steps, then start dribbling your soccer ball again.

Again, I’ll randomly call out colors and try to hit 3–5 rounds of each color. In this section of the warm-up, they end up doing double-leg hopping, skater hops, quick changes of direction, and some single-leg balance. In this entire technical warm-up example, the athletes not only perform movements often seen in effective IPPs, but they also get touches on a soccer ball, which helps with their technical skill development and coach and player buy-in.

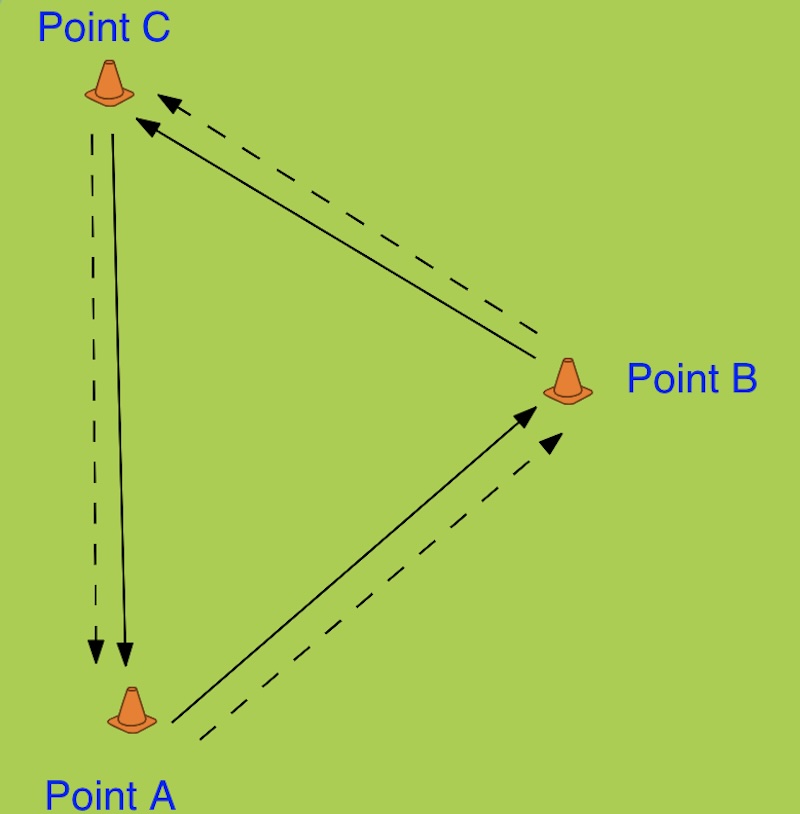

If the team’s technical warm-up consists of passing patterns, you can also add in the exercises that are part of an IPP. For example, a common passing warm-up in youth soccer is to have four players in a triangular shape with two players at one point (point A) and one player each at the other two points (points B and C) of the triangle.

One of the players at point A has a soccer ball and passes to the player at point B. Player 1 then follows their pass and runs from point A to point B. Player 2 receives the ball, passes to player 3 on point C, and then runs from point B to point C to follow their pass. This continues with players passing the ball to the next player and following their pass on the jog.

Instead of jogging, though, the players can be instructed to perform movements that are part of an IPP. The path from point A to point B can be a jog, point B to point C can be a side shuffle, and point C to point A can be a backpedal. After a couple of rounds, have the players change directions with their passes and change the movements. So now, point A to point C is bounding, point C to point B is a single-leg hop, and point B to point A is a high skip.

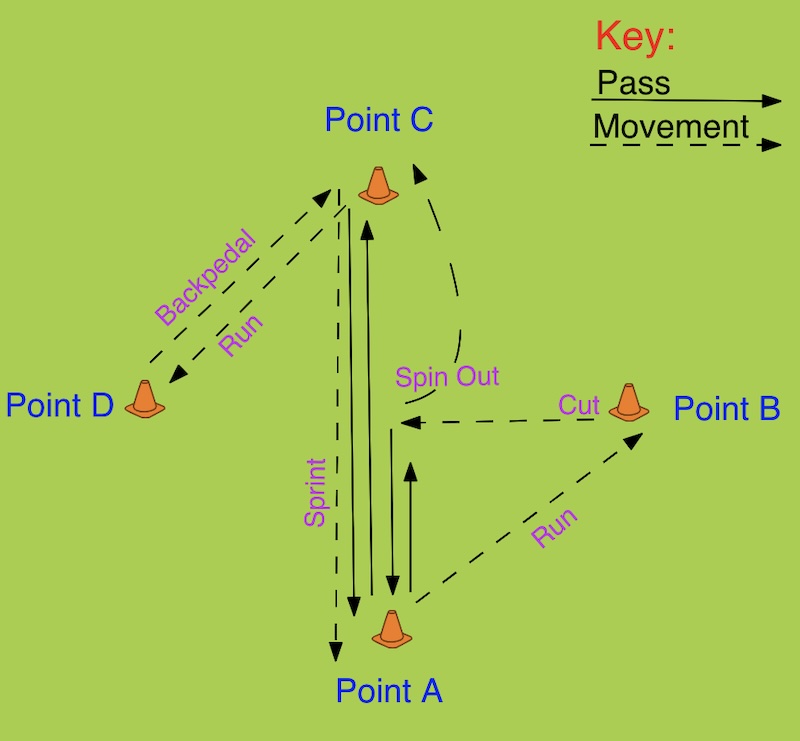

The passing pattern can then be varied to mix up the technical component and introduce further IPP movements. Now, have discs set up in a diamond shape with players lined up across from each other at points A and C.

Player 1 has the ball at point A and passes the ball to player 2 at point C. Player 1 then runs to point B and cuts inside to the middle of the diamond, while player 2 passes the ball to player 3 at point A. Player 3 does a short pass to player 1 inside the diamond, who passes it back to player 3 in one touch and then spins out and runs to the end of the line at point C. Player 3 then plays a long pass to player 4 at point C and repeats the same process that player 1 had previously done.

Meanwhile, player 2, who had initially received the ball from player 1 at point C and then played a pass to player 3 at point A, will run to point D, backpedal to point C, and then sprint to the end of the line at point A. From a technical perspective, this warm-up includes one-touch, short, and long passes. From an IPP perspective, it includes changing direction, multidirectional running, and sprinting.

While the athletes do the exercises, I explain which parts of the body the exercises address and why they’re so important to help decrease the risk of injuries in those areas, says @NSurdykaPhysio. Share on XI mentioned earlier that part 2 of the 11+ can be moved to the end of practice to help with buy-in and still be an effective way to reduce the risk of injury. I also try to do these exercises with the athletes while the parents are there so that the parents can see them, too. While the athletes do the exercises, I explain which parts of the body the exercises address and why they’re so important to help decrease the risk of injuries in those areas. This helps to increase player motivation and gets the parents bought in and educated on what they can potentially do at home as well.

These are the exercises I typically do with the athletes at the end of the session and how I coach them:

-

- Squats – Keeping your feet flat on the floor, lower down like an elevator, and stand back up. If I notice that athletes have their feet really close together or really far apart, I’ll tell them to stand with their feet on either side of the soccer ball (most kids don’t understand the concept of putting their feet hip-width apart).

-

- Lunges – Take a step forward, bending both knees, then step back again. Usually, a demonstration works best for a lunge. I also tell them to pretend there’s a laser beam coming out of their kneecap, and I want them to keep that laser beam pointed right in front of them the whole time.

-

- Heel Raises – Go up onto your toes and then slowly lower down again. I often have them do this while holding a partner’s hands for balance.

-

- Planks – Make your body as straight as a board and try to freeze in that position. I’ll go around while they do this and kick a soccer ball underneath them to make sure they aren’t sagging their hips down, or I’ll tap on their lower back if they have their hips up in the air too high.

-

- Copenhagens – Lift the inside of your shoe up to the sky. I always start with Level 1 Copenhagens, in which they are lying on their side.

- Nordics – Make your body as stiff as a board, kick your heels up into your partner’s hands, and lower yourself down to the ground as slowly as you can. It takes kids a couple of sessions to understand how to do this exercise correctly, and they usually need some hands-on guidance. Don’t get discouraged—they can and do learn how to do this pretty well with enough practice.

Where Does Dynamic Stretching Fit In?

So, I covered running exercises, changes of direction, and plyometric exercises within the technical warm-up. I also discussed that strengthening exercises can be done at the end of the session to help improve implementation and explained how I typically do that. One thing I have not yet addressed is stretching.

Some IPPs include dynamic stretches, but they have not been shown to be a vital aspect for effectively reducing injuries. However, there are times that I’ll include a few dynamic stretches if time allows. When I do include some dynamic stretches, I always make sure I add some player education simultaneously. Usually, I’ll include a walking quad stretch, walking calf and hamstring stretch, and lateral lunges.

As the athletes do the stretches, I tell them what part of the body we are focused on (quads, calves, hamstrings, and adductors/groin) and explain that those are the areas used most in soccer. My intention in doing this is simply to educate the athletes on their bodies. Most kids won’t actually feel any stretch, and that’s okay. These are still good movements for youth athletes to do whether they feel a stretch or not (single leg balance, lunging, reaching, etc.).

Most kids won’t actually feel any stretch, and that’s okay. These are still good movements for youth athletes to do whether they feel a stretch or not, says @NSurdykaPhysio. Share on XThe warm-ups I just used as examples are simply that—examples. The exercises that are done are representative of some of the components in IPPs, like the 11+. They can (and should) be varied and progressed as the athletes become more adept at performing them.

Coaches should be educated on how to progress and coach these exercises. It’s helpful to teach principles instead of scripted progressions because coaches can feel comfortable varying and progressing the exercises to suit their team. Here are some general principles that might help coaches progress the exercises in an IPP warm-up:

- Start double leg and progress to single leg.

- Double-leg jumps over the ball to single-leg jumps over the ball.

- Start with lower hops and progress to higher jumps.

- Hops over an invisible line on the ground → hops over a disc → hops over a ball.

- Use the first section of the warm-up for running-based movements such as jogging, side shuffling, and some change-of-direction tasks. Use the second part of the warm-up for jumping, hopping, and more challenging change-of-direction activities.

- Simple → Complex

- For younger kids or novice players, start with simple, one-step instructions. “When I say the color green, jump over the ball.” With older or more experienced athletes, you can add some complexity to the instructions. “When I say the color green, stop your ball, run to a different ball, do five juggles, and then backpedal back to your ball.”

- Note: You can also add a bit more of a cognitive challenge in your instructions. “When I say something that is the color green (like celery or grass), do five squat jumps.”

It’s also essential that the athletes are not simply given instructions on what to do but are shown and told how to do the movements as well. It’s important for kids to be able to explore various movement patterns and come up with their own solutions to motor challenges, so we don’t want to overcoach them, but we should still give them some cues.

Here are some of the cues I typically use with youth soccer players:

- Jumping and landing exercises: When you land, I don’t want to hear a sound.

- Changing direction: Get low to the ground and look up to make sure you can still see the ball and players around you.

- Side shuffling: Don’t click your heels.

- Note: I used to say, “Don’t click your heels; you aren’t Dorothy trying to go back to Kansas,” but I’m finding that many kids these days haven’t seen “The Wizard of Oz,” so this cue has been less effective.

- Single-leg balance: Freeze like a statue.

Making a Difference at the Youth Level

In summary, IPPs like the 11+ effectively reduce the risk of injuries, but only when adhered to. It’s important to start IPPs at the youth level; there are, however, several barriers to implementation. Coaches should be the ones delivering IPPs at the youth level, which means our roles as healthcare and performance professionals need to shift away from the delivery of IPPs and toward the education of coaches. The barriers facing youth coaches need to be addressed, including the lack of confidence in knowledge and ability to deliver IPPs, session time, and field space.

Coaches should be the ones delivering IPPs at the youth level, which means our roles as healthcare and performance professionals need to shift toward the education of coaches, says @NSurdykaPhysio. Share on XIntegrating aspects of a successful IPP into a technical warm-up and moving the strengthening exercises to the end of the session are two tactics to help reduce the real and perceived barriers faced by youth coaches. Teaching coaches principles rather than scripted warm-ups might give them more confidence in their ability to program and progress IPPs into their sessions based on their team’s needs and abilities.

Lead Photo by Andy Mead/YCJ/Icon Sportswire

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Thorborg K, Krommes KK, Esteve E, Clausen MB, Bartels EM, and Rathleff MS. “Effect of specific exercise-based football injury prevention programmes on the overall injury rate in football: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the FIFA 11 and 11+ programmes.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;51(7):562–571. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097066

Al Attar WSA, Yamani SA, Alharbi ES, et al. “283 Sports injury prevention programs: awareness, implementation and opinion of physical therapists worldwide.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021;55:A110.

Minnig MC, Hawkinson L, Root HJ, et al. “Barriers and facilitators to the adoption and implementation of evidence based injury prevention training programmes: a narrative review.” BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 2022;8:e001374. doi:10.1136/ bmjsem-2022-001374

Whalan M, Lovell R, Steele JR, and Sampson JA. “Rescheduling Part 2 of the 11+ reduces injury burden and increases compliance in semi-professional football.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2019;29(12):1941–1951. doi:10.1111/sms.13532

Bizzini M and Dvorak J. “FIFA 11+: an effective programme to prevent football injuries in various player groups worldwide-a narrative review.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;49(9):577–579. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094765

Arundale, A.J.H., et al. (2023) “Exercise-Based Knee and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention.” The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 53(1), pp. CPG1–CPG34.

Bogardus, R.L. et al. “Applying the Socio-Ecological Model to barriers to implementation of ACL injury prevention programs: A systematic review,” Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2019:8(1);8–16.

Geertsema, C. et al. “Injury prevention knowledge, beliefs and strategies in elite female footballers at the FIFA Women’s World Cup France 2019,” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021;55(14):801–806.