[mashshare]

Collectively, strength and conditioning professionals need to help raise the standards of the profession, and one important way to achieve this is by setting institutionalized procedures and best practices. The CSCCa and NSCA Joint Consensus Guidelines for Transition Periods is a positive step in the right direction and provides a valuable resource for coaches to use when onboarding student-athletes.

When an athlete steps off-campus for summer or winter break—or is a new athlete entering your program—their true training history is unknown. Maybe they worked out at their high school or a local private facility, but unless you are in constant communication with these athletes, there’s a good chance you’re in the dark. Did they follow a progressive resistance training program? Were they on a running program that established a foundation for summer conditioning equivalent to the athletes currently on campus?

For the most part, the answers most likely are no—therefore, it’s your responsibly as a coach to meet them where they are currently. It’s also critical to establish open lines of communication with other key support staff members who impact the student-athletes.

This article will cover two key topics:

- How we onboard incoming freshmen and transfers, outlining the standard procedures that help us run our program effectively.

- How we communicate and collaborate with sports medicine and use other operating procedures to serve our student-athletes best.

Having a plan and a process allows you to have professional guardrails in place to improve outcomes and athlete safety.

Challenges with Incoming Freshmen and Transfers

Most coaches I’ve talked to around the country have the same struggles when trying to onboard new athletes into their program. Although every university has its own unique set of challenges, here is a list of some of the issues most commonly faced.

Unknown training history. Athletes report to campus from all over the world, and their training history and background can vary significantly. I’ve had freshmen come from places like Cressey Sports Performance with great training backgrounds and others who have never set foot in a weight room before entering ours.

Short acclimation period (fall teams). Many of our fall sport teams have 10-14 days of practice before their first official game, offering little to no time to train optimally. And freshmen and transfers often compete for playing time immediately.

Structural imbalances. With athletes specializing earlier, we see many athletes come in with imbalances and movement deficiencies. For example, a basketball player might arrive on campus with a 40-inch vertical but still can’t do a lunge without losing balance.

Integrating freshmen and transfers with the returners. It is easier said than done to have multiple programs going on at one time in your facility—especially if you’re running the sessions single-handedly.

Steps to Address These Challenges

Step 1. Put all new athletes on the Block Zero program. More on this below.

Step 2. Juice up your internship program. Tap into your campus resources and local exercise science departments to improve your internship program. With multiple programs going on in one session, you need more eyes on the floor. On campus, we use the physical therapy, health science, and nutrition departments for volunteers, interns, and work-study students. Our internship coordinator also has established relationships with several local universities that send us full-time semester interns. As our internship program has grown, we’ve had several certified post-graduate interns looking to gain experience, as well. This takes some work on the front end, but in the long run, it can really help you grow your department.

Step 3. Institute an “all hands on deck” approach when necessary. If you don’t have enough help, use full-time staff who work with other teams during the onboarding phase. It’s never a bad thing to have other coaches from your staff get to know other student-athletes.

Step 4. Use overtime cards. Once athlete deficiencies are recognized, we prescribe the athletes individualized corrective exercises or short workouts to do with the training program either before or after workouts (or on a separate day). This allows us to individualize training and give athletes extra work based on their needs. For example, if an athlete is struggling from a conditioning standpoint, they might do bike intervals while an athlete with poor core strength does extra suitcase carries, planks, and Pallof presses.

Establishing a Block Zero Program

We took this concept from Coach Joe Kenn, Head Strength and Conditioning Coach of the Carolina Panthers. Regardless of the sport, we have every new athlete complete our Block Zero program. Athletes must pass competency in each of our main movements before progressing to more advanced movements. We’ve had this system in place as a department for the past three years, and it has allowed us to:

- Teach and enforce proper movement from Day 1

- Safely progress athletes with varying training histories

- Separate the incoming players from the returners so we can have more eyes on them during a critical period

- Create good training habits and break bad ones

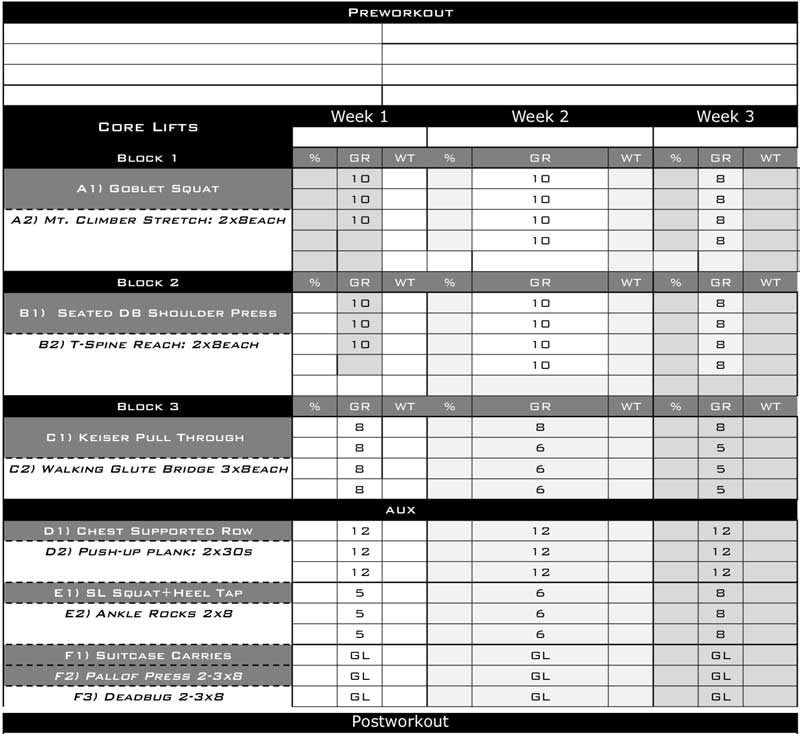

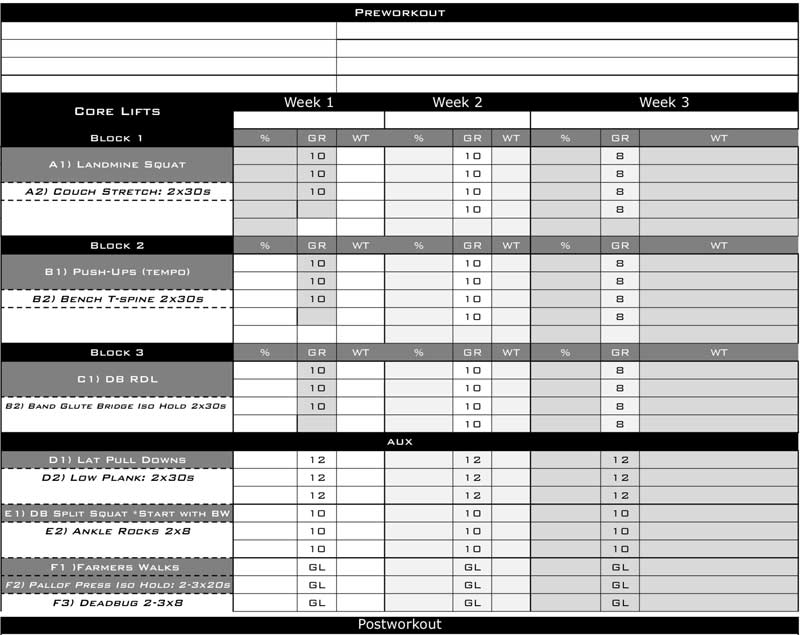

Incoming freshmen who play a spring sport are split from the returners during the session and have a completely different program. For those who compete right away in a fall sport, we use the Block Zero exercises to replace our more advanced exercises used by the returners. For example, if our upperclassmen are front squatting, the freshmen will do landmine or goblet squats. If our upperclassmen are barbell benching, our freshmen are doing tempo push-ups or DB bench press. This lets us keep everyone together to account for the demands of the hectic in-season schedule.

A question I often get from other strength coaches is, “Do your sport coaches have any issues with this?” In three years, we haven’t had one coach question this program. If anything, they appreciate that their athletes will be taught how to do everything the right way while we continue advancing and pushing the returning players.

Below is the bank of exercises our coaches can choose from when designing their Block Zero program. If you have more advanced freshmen or transfers, you can continue to challenge them within these parameters. For example, you can add tempos to a landmine squat or a vest to the single-leg squat.

- Squat Pattern: Banded BW Squat, Goblet Squat, Landmine Squat

- Hinge Pattern: Dowel Hinge, Band Good Morning, DB RDL, Band Pull Through

- Single Leg: BW SL Squat (off a short box), BW or DB Split Squat

- Press Pattern: DB Bench Press, Tempo Push-Ups, Seated DB Shoulder Press

- Pull Pattern: Chest Supported Row, Lat Pull Down, Cable Rows

- Core: Suitcase Carries, Pallof Press (and variations), Dead Bugs, Farmers Walks, Plank Variations

Below is a sample of one of our original programs. We paired each exercise with a corrective to help improve the quality of the movement, and each week the athletes progress in either load or volume.

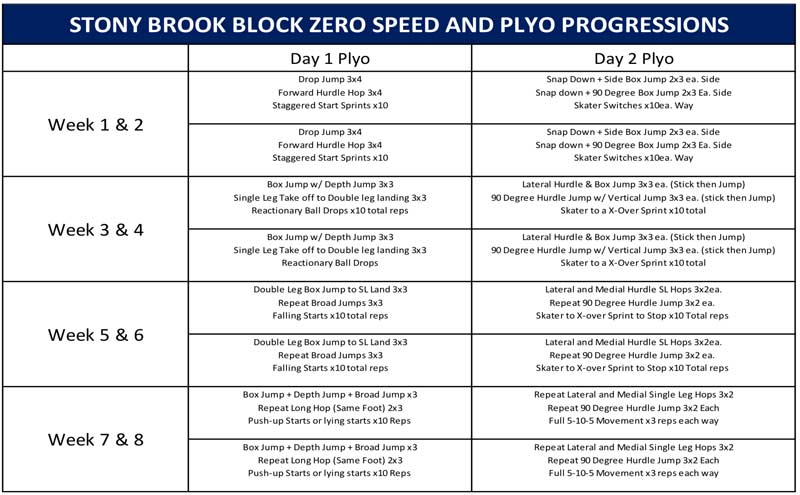

In addition to our weight room progressions, we have speed and plyo progressions. You can see an example 8-week outline below. We used Complete Jump Training by Adam Feit and Bobby Smith as a resource to develop this program. While many of our athletes come in with great athleticism and impressive vertical jumps, most of them struggle with the ability to land correctly. This program has been extremely helpful for us to coach and progress jumps and movement in the same capacity we do our compound lifts.

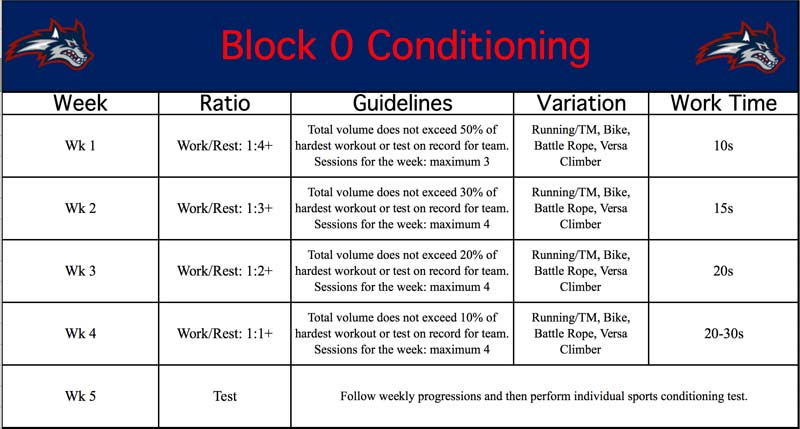

Lastly, below is an outline of our 5-week conditioning progression for incoming freshmen and the acclimation periods. The set work/rest ratios allow each coach the flexibility to use different methods while sticking with parameters that safely progress the athlete. We designed this program based on the guidelines set by the CSCCa and the NSCA. We implemented this protocol over the previous summer and found it provides the right ratio for groups of athletes who have varying training histories.

For example, we had one group of incoming players that included a junior college transfer, a true freshman, and a true freshman coming off a minor injury. The program was relatively easy for the junior college transfer, challenging for the true freshmen, and hard but appropriate for the freshman coming off an injury.

Results of Our Block Zero Program

Reduced injuries. Since implementing these programs across the board, we’ve seen a significant decrease in injuries with incoming freshmen, both in the weight room and on the playing field or court.

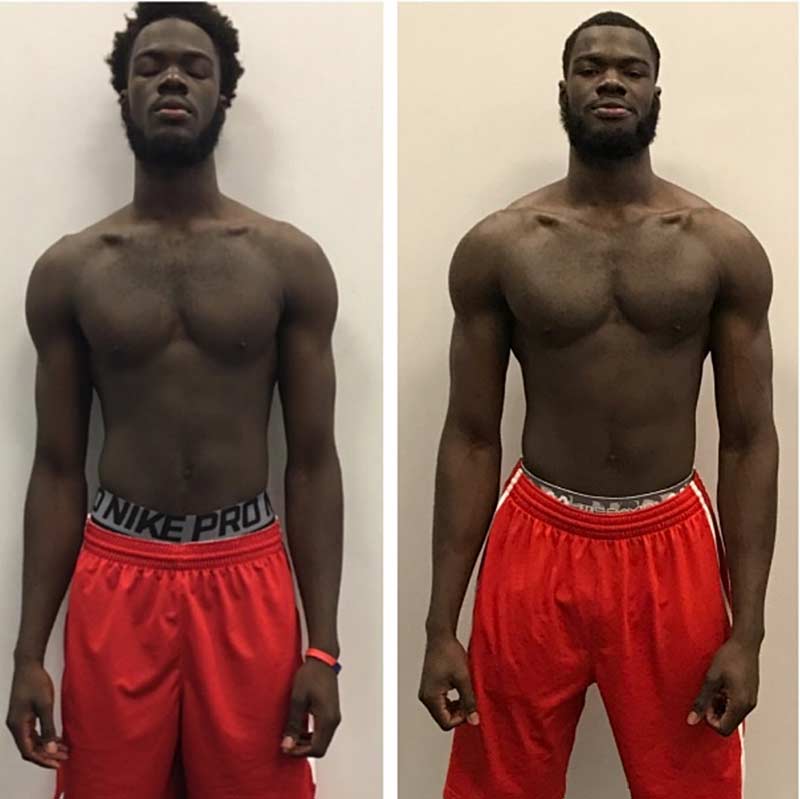

Improved performance. The before and after photo below is the 9-month transformation of a former student-athlete. He was a junior college transfer who had done no formal training before stepping on campus—and at 6’7 with a 7’0 wingspan, weight training didn’t come naturally for him. In his first year, he was a starter right away for us, and we did not deviate far from the sample weightlifting program shown above. Combined with improving his diet and consistently working hard every single day, he put on 28 lbs and increased his vertical by 3.5 inches during a season in which he started all 33 games.

Our first-year men’s basketball players average a 10-pound gain in body weight & a 4-inch vertical jump increase, says @GreeneStrength. Share on XWith our men’s basketball program, we’ve seen an average body weight increase of 10lbs and a vertical jump increase of 4 inches for first-year players in our program. In short, it doesn’t take an advanced program for someone new to training to make extraordinary progress.

Increased buy-in from coaches and sports medicine. Since there is a clear understanding of what a large population of student-athletes will do when they first start in the weight room, our coaches, sports medicine staff, and athletic performance staff are all on the same page, which leads directly into my next topic.

Common Communication Challenges with Sports Medicine

Our communication and collaboration with sports medicine are critical for the development and health and safety of our student-athletes. These two groups need to work closer than any other support units in the department. Both strength and conditioning coaches and athletic trainers spend a great deal of time with the student-athletes and can make a tremendous impact when they’re on the same page.

Ego. One of the most common issues with strength and conditioning coaches and athletic trainers around the country is ego. In most cases, one person believes their job is being done by the other. Another contributor is the lack of understanding of each role.

Return to play programs. If there is no structured process for return to play protocols as athletes transition back into the weight room, you’re doing your athletes a disservice and setting yourself up for conflict between the two parties. All athletes need to be treated as individuals when they are coming back from injury. And protocols that we’ve discussed, reviewed, and agreed upon give everyone involved peace of mind. Why would the athletic trainer want to turn the athlete over to strength and conditioning staff if there isn’t a plan in place? Adjustments can be made as you go, but have a structured program in place.

Poor communication. A lot of issues that arise across the board in any field come down to poor communication. A poorly worded email or text, forgetting to send a response to a message, or leaving someone out of a discussion can cause problems even when it wasn’t intentional.

Lack of collaboration. The reality is both fields have a lot of crossovers, especially regarding areas like flexibility, recovery, and nutrition. Naturally, people tend to grab hold of things instead of using each other as a resource. And for those strength and conditioning coaches and athletic trainers responsible for multiple sports, the communication might be limited to just an email or two per week or catching up in the hallway if they ran into each other, which causes miscommunication.

Athletic trainers and S&C coaches who travel and attend practice together have better relationships, trust, & collaboration, says @GreeneStrength. Share on XWe found that teams that have an athletic trainer and a strength and conditioning coach who traveled and attended practice together always had better relationships, trust, and collaboration. This was due to the amount of time spent together during the year with road trips and long practices. The head athletic trainer and I worked together to put protocols in place that allowed staff members the opportunity to create relationships.

Steps to Address Communication Challenges

Meetings. Each ATR and S&C meet at least once per week (outside of practice) to discuss the athletes in general, what they see in the weight room, current training program, current rehab programs, etc. This not only keeps everyone on the same page when it comes to the athlete, but it also helps improve the relationship and trust between the two groups.

Aligned hours. We do not open for any weight training or conditioning sessions unless someone is present in the training room.

Return to play programs. All athletes returning from concussions or surgery of any kind have set protocols agreed upon by both the athletic performance staff and the athletic training staff. We also have a staff member who has a primary administrative assignment to oversee the programming and progression for each athlete coming back after surgery.

Individual screening process. Our athletic performance staff and athletic training staff work together to screen all incoming student-athletes and create protocols specific for each team. For example, our basketball program will do a series of jumps on the force plate, an overhead squat, and a single-leg squat test while our baseball program will go through a completely different assessment. This helps us identify structural imbalances and performance strengths and weaknesses and also pushes members of both staffs to work together and be on the same page.

Group staff meeting. Two years ago, we organized a meeting with both staffs and laid out an overview of communication expectations as well as any coordinated projects between the two groups to keep everyone on the same page. At the start of each academic year, we get together to lay out any new plans for staff members joining the department.

Results of Increased Communication

Improved working relationship. The scheduled meetings significantly increased the trust and respect between the two groups, and the miscommunications slowly disappeared with this collaborative approach.

Friendships. Many of the staff members have become friends outside of work. Friendships are not a necessity but have brought the two groups closer together which, in turn, has positively impacted the student-athletes.

Ego is left out of it. When you get to know someone, you usually understand their intentions better and don’t take things personally. The increased communication has allowed all parties to do what is best for the athletes, regardless of who comes up with the idea.

Positive crossover. Because of the nature of the strength and conditioning and athletic training professions, there will be some crossovers. Athletes might come into the weight room to roll and stretch, or they might go down to the training room. We use the overtime cards for athletes who have pre-existing injuries and need some extra work but not necessarily one on one treatment in the training room. These are two examples of how having everyone on the same page can save everyone time. It also allows athletes who might need specific individual attention with a trainer to get better while athletes who just need maintenance work can fit it into their routine.

Other Effective Operating Procedures

High-performance meetings. Last year, we began having high-performance meetings with several teams, which included the sport staff, strength and conditioning, athletic training, and academics. In-season teams would meet once a week, and off-season teams would meet bi-weekly. The meetings helped everyone stay on the same page regarding logistics like travel, schedule changes, or tough academic periods. It also helped keep everyone in tune with athletes having a tough time and managing the load of the athletes.

Athletic performance meetings and chalk talks. Every Friday, my staff and I get together and recap the week and discuss new training blocks for our teams. For example, if women’s soccer is about to start a new program, their coach will print copies of the plan and walk the entire staff through their thought process, bouncing ideas off everyone in the room. The process also lets us make sure we don’t have any holes in our programs and serves as a good opportunity for young coaches to practice describing their plan before they speak to the head coach.

Credentials. The fact that there are still people in collegiate strength and conditioning without earning certifications through the NSCA or CSCCa is scary. As a department leader, it’s your job to make sure that every member of your staff is certified and maintains their certification throughout their employment at your university. This is something every director should do at each institution to improve how we’re viewed as a profession.

Safety in numbers. Football obviously requires more attention than other sports in addition to larger teams like lacrosse and baseball. With these teams, we do everything in our power to get as many eyes in the room as possible. Sometimes that calls for all hands on deck or asking two coaches on staff to partner up on a team. Growing our internship program also has helped us with this.

Reporting lines. All athletic performance staff members report directly to me as the Associate AD for High Performance.

Pre-workout fueling. We do everything in our power to make sure the athletes have something in their bodies before each session. While educating them on the importance of eating before training is important, we go a step further to ensure they are prepared to work out. Snacks like bananas, chocolate milk, and granola bars are in our facility and available before any training session.

In-services. We aim for quarterly in-services or Skype sessions with programs and individuals around the country. One presentation that has benefited us from a health and safety perspective is from Josh Bullock, the Athletic Development Coach for US Ski and Snowboard. His topic was “Managing Common Health Conditions Encountered by the Exercise Professional,” which covered managing athletes with sickle cell, diabetes, spondylolisthesis, and asthma, among others.

Wrap Up

These protocols and policies have developed over time and continue to evolve each year. My staff and I at Stony Brook have chipped away at these to best serve our athletes during the last four years. Credit goes to my initial staff: Vincent Cagliostro, Director of Athletic Performance for Football at Stony Brook; GC Yerry, Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach at Army West Point; and Patrick Cummings, Director of Football Performance at Buchholz High School for collaborating on the original protocols as well as my current staff—Kaitlyn Newell, Joe Quattrone, Joel Lynch, Kelly Cosgrove, and Rob Deese for bringing new ideas and updating these protocols each year.

The big takeaway from this article is for coaches, administrators, and high-performance professionals to look at their situation and address their unique problems in a systematic way—not necessarily to adopt these exact procedures.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]