I know what you are thinking: “Who is this kid writing about lessons he’s learned after only five years in the field? Doesn’t he know Michael Boyle recently wrote one from 40 years of coaching that has WAY more wisdom packed into it?”

Yes, in fact I have read several articles in that type of style and enjoyed them so much that I wanted to write my own—so, shoutout to those coaches for inspiration! Obviously, this won’t be as impressive as Coach Boyle’s, but on the bright side for you, it’ll be MUCH shorter. While Coach Boyle has more wisdom to share than I do, I hope that my unique situation coaching at a small Canadian university can resonate with many readers and provide some takeaways.

I recently celebrated my 5th year of being the Head Strength & Conditioning Coach at Trinity Western University, and in that short time I have learned MANY lessons. I wanted to boil it down to just five—so, while this won’t be as wisdom filled as a “40 years in the field” article, hopefully it can help those of you just getting started and make those early years a bit smoother.

1. Relationships Trump ALL

This one might seem obvious, but it still needs to be stated. As S&C/Performance Coaches, we work with people. They might be high school kids, student athletes at the college level, or professionals. Doesn’t matter—people are people, and being able to work with them is the most important part of your job. I have heard so many of my colleagues say that it is better to be a good person first (or a “certified nice person,” as Coach Boyle puts it) and then learn the science of training second. Way easier than trying to nerd out on the science and pick up the people stuff later.

I recently reread the principles from “How to Win Friends and Influence People” by Dale Carnegie (which is the best book on this topic), and they all still ring true. Smile, don’t criticize, give praise—these are all staples in my coaching, because I have learned that being a “good guy” is the easiest road to being a “good coach.”

How so?

Well, early on in my career I had good mentors show me the ropes. Plus, when I was an intern, I struggled with showing how much I cared and often started by spitting science at people. Through the direction of my supervisors, I studied human behavior and tendencies, learned to communicate better…and lo and behold, it worked! Results are important, of course, but you are better off spending the first part of your career developing good relationships so that people know you care and know you want the best for them, and then you can get blood from the stone.

Results are important, of course, but you are better off spending the first part of your career developing good relationships so that people know you care and know you want the best for them, says @chergott9. Share on XAfter all, it’s true… “Nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care.”

2. Study. Hard.

One of my favorite ways to sum this one up is this: We all talk about athletes that are difficult to deal with and just throw up our hands and say “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make them drink.” My response is then: “Is the water you are leading them toward going to give them the nourishment they need?”

Yes, it is crucial to be a nice guy/girl (as I just finished saying), but it should also go without saying that you need to know your stuff when it comes to athlete preparation. The best way to get buy-in and build trust is to deliver results.

I got caught with this early in my career. Athletes would question the why of our training and I would throw out stock answers that would suffice for the time being, but then when sport coaches demanded more results and I had no answer to give them as to why we were failing to get them, I knew I needed to step up my game.

So, I went back to my university study habits and started creating a study schedule by creating “Reminders” of things I wanted to touch on each day. That way, I don’t get to check them off until I’ve done them—and as a Type A personality, this works for me (very well I might add). Things I have on my daily reminders list include:

- Study a sport

- Study sport science

- Read an article

- Reach out to a colleague/friend

These have helped to ensure I take time each day to learn, to grow and get better as a practitioner, and to go on countless Zoom calls and make site visits asking all my questions. This has not only led to better results for my athletes, but providing better explanations as to why we are doing certain training methods and exercises instead of just relying on doing what my mentors did. Plus, it has helped me develop a critical thinking brain, so I don’t just fall for the latest trend—I can stick to my guns because I know what we do works and I also know why (and how to communicate that effectively to my athletes and coaches).

3. Be a Role Model

I don’t mean you need to have an eight-pack, go for 10km runs every morning, and never get less than 8 hours of sleep—but, it helps to at least be a healthy person (or at least push yourself to be better in this area) so you know what it is like.

Get under the bar and train yourself, hard. Do conditioning work. Try out things you plan to have your athletes do before just throwing it at them. Sleep as much as you can and eat healthy. I know these are super general suggestions, but that is because it will look very different for everyone and in every context.

Get under the bar and train yourself, hard. Do conditioning work. Try out things you plan to have your athletes do before just throwing it at them. Sleep as much as you can and eat healthy. Share on XAs a dad of two girls under the age of three, I know what it is like to lose sleep—so, I can relate to my athletes and chat with them about strategies I use to maximize what I get, ideally helping them to do the same during paper/midterm season. I used to compete in Olympic Weightlifting, so I know what it was like to do exercises you hated that your coach programmed.

Now that I’ve retired from lifting competitively, I’ve really taken a dive into different training and conditioning protocols and have found that it makes it way easier to communicate the why and the how when you have personally done and experienced it. For example, over Christmas break I was experimenting with some bodyweight/low-equipment circuits for our athletes to do over similar breaks where they might not have access to a training facility or equipment. It sucked, but was doable so I knew I could give it to them with success. Yeah, they hated it too—but it got results!

Video 1. Bench Press.

Video 2. Loaded Chin-Ups.

I train myself and post some of those clips (especially PRs) on social media and YouTube (see above). When your athletes know you go through the ringer too, that helps them trust you as you hopefully know what they are feeling when they do a brutal set of 10 squats. It is much easier to trust someone who is willing to do what they prescribe instead of just reading what the research says from your ivory tower.

4. Write Plans in Pencil

This one can be summarized in one word: COVID. I started my tenure here at TWU during the spring of 2019, with the tail end of my first year being cut short due to the pandemic. Now, if I didn’t already do so before that, I learned to hold plans loosely and plan in pencil, not pen. Basically, just meaning that you need to be ready to adapt at any time, each and every day.

This could come in the form on an injured athlete needing a modification, a team being bagged in training right before lift due to poor performance, or obviously a global pandemic.

What I found the best to be able to help with this one is the first two lessons I mentioned: If you study hard and know your stuff and your why for programming, it is much easier to find alternative solutions based on injury or load management. And by having those great relationships, you can easily communicate why we are making the adjustment or maybe why we aren’t going to. But it all has to come from that level of love and trust you have built.

If you study hard and know your stuff and your why for programming, it is much easier to find alternative solutions based on injury or load management, says @chergott9. Share on XAnother strategy that helps with this is realizing that you are not the center of the world—most athletes don’t like lifting weights, and they came to this school to play the sport, NOT work with you. When I put all that into perspective, it helps take off some of the pressure I put on myself to be the best and for ME to be the one to make my athletes better. At the end of the day, running one recovery session on Squat Day ain’t gonna hurt.

5. K.I.S.S.

In my second year I thought I was really starting to get the handle on programming here. I was learning so much (see point two) and was incorporating as much as I could into my programs. We were hitting ALL the prehab, ALL the sport specific work, and ALL the niche things I learned.

Guess what was missing? A large enough dose of the basics that actually work.

It took one of our older athletes to have a meeting with me to explain how he felt about the program for me to realize that I had gotten away from the main thing for athletes at this level, which is usually just getting bigger, faster, and stronger so they can stay healthy and play their sport at a higher level.

Since then, I changed my laptop background to “KISS” (Keep It Simple, Stupid), trimmed my programs down and stuck to the basics that work. Sure, there are times I add new stuff and venture out, but those times become the exception, not the rule. “Master the box before you leave it” is a concept I now hold dear when I think about adding in something. Since then, my programs have gotten great reviews! No, they are not perfect and there is still tons to learn, but I have found that most athletes…

- Don’t want to do a bunch of fluff but just train hard.

- Don’t have time to do all the fluff.

- Benefit WAY more from just keeping it simple.

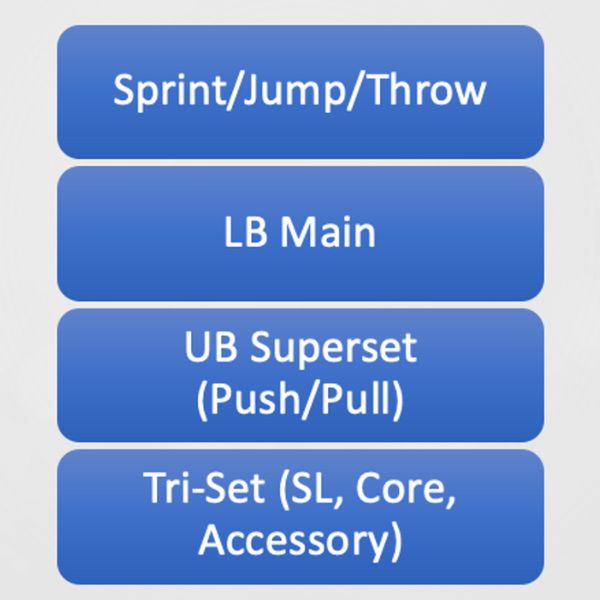

So, I have developed a simple program template that I follow 90% of the time, with some deviation of course to try new things as mentioned. But, by keeping it simple (stupid), our results have improved and as mentioned, been enjoyed way more—which has vastly improved buy-in and effort.

Onward

So, there you have it, short and sweet (until I get to 40 years, like Coach Boyle).

Build relationships. Study. Be a role model. Be ready to adapt. Keep it simple. All helpful tools that I have learned, and I now you have too! At the end of the day, being a Strength & Conditioning Coach is the best job in the entire world (I mean where else can you work in shorts and sneakers every day while listening to rap music?). So, enjoy the journey and remember that you will make mistakes along the way. Those mistakes are what will help you correct your course and become the best coach you can be.

Good luck.

Peace. Gains.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF