Do you want to jump higher and play better volleyball?

Whether you’re spiking, blocking, or just trying to reach the ball, a higher vertical jump can make all the difference.

This article will show you some great exercises for your warm-ups, flexibility, and strength that’ll help you increase your vertical jump for volleyball.

Let’s jump in!

Understanding the Vertical Jump in Volleyball

In volleyball, jumping high is very important.

It lets you get a better angle and more force behind the ball when spiking, gives you a more effective block, and allows you to serve higher up in the air.

It’s an all-around advantage that every volleyball player wants.

Exercises to Increase Vertical Jump for Volleyball

First, let’s look at some exercises you can do as a warm-up and to improve flexibility, as that’ll let your muscles be primed for some serious jumping.

Then, we’ll look at some specific strengthening exercises before moving into plyometric and volleyball-specific drills.

We’ll include some recommendations in terms of sets and reps, but remember that those can change depending on your current routine and fitness level—that said, these are a good place to start.

Warm-Up Exercises

Warming up is the first step to jumping higher.

A good warm-up gets your blood flowing and your muscles ready for work.

Here are two quick warm-up exercises:

-

- Leg Swings: Swing one leg forward and backward, then switch legs. Do 2 sets of 15 swings on each leg.

- High Knees: Run in place while lifting your knees as high as possible. Do 2 sets of 30 seconds.

Flexibility & Mobility Drills

Stretching helps you move better and can prevent injuries.

I generally recommend you do some stretching only after you warm your muscles up, as they don’t really like to be stretched when they’re cold.

Here are some stretches to try:

-

- Hamstring Stretch: Sit on the ground with one leg out and reach for your toes. Hold for 30 seconds on each leg for 2 sets.

- Quad Stretch: Stand on one leg, grab your ankle, and pull it towards your butt. Move your knee behind you for an extra stretch. Hold for 30 seconds on each leg for 2 sets.

Strength Training Exercises

To get the highest jump possible, training your legs and your core will be the best bang-for-your-buck.

It’s a good idea to build different types of strength, as that’ll make you more well-rounded:

Lower Body Strengthening

It’s simple math: strong legs generate more force, equaling a higher jump.

You want to work on both bilateral and unilateral exercises, especially since you’ll often be jumping off of one foot or in a staggered position.

There are many great exercises to build some serious lower body strength, but these are tried-and-true:

-

- Squats: Stand with feet about shoulder-width apart, bend your knees, and lower your body like you’re trying to sink your hips between your legs. Shoot for 3 sets of 8-12 reps, focusing on lowering slowly and coming up explosively.

-

- Lunges: Step forward with one leg and bend both knees to lower your body. Do 3 sets of 10 reps on each leg. You can do these alternating, in a split lunge style, or walking. If you want a real challenge, try Bulgarian split squats.

- Deadlifts: Lift a weight from the ground by bending at your hips and knees, then standing up straight. Do 3 sets of 5-8 reps.

Core Strengthening

A strong core helps you jump with more power, and also helps you transfer energy through your body more efficiently.

Try these exercises:

-

- Planks: Hold your body in a straight line, supported by your arms and toes. Hold for 30-60 seconds, 3 times. A great tip I like to use here is to squeeze your glutes hard, it’ll force you into an ideal plank position.

-

- Russian Twists: Sit on the ground, lean back slightly, and twist your torso side to side while holding a weight or medicine ball. Do 3 sets of 20 twists. Bonus points if you raise your feet off the floor.

- Hanging Leg Raises: Hang from a bar and lift your legs up to your chest. Do 3 sets of 10-12 reps. You can regress this by lifting your knees up instead of your entire legs.

Plyometric & Explosive Exercises

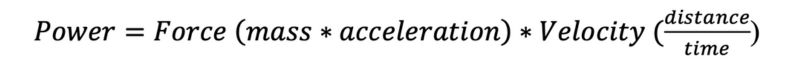

You need both strength and power to get the best height.

And, jumping is all about exploding off the ground, which is where plyometrics and explosive movements come into play:

Plyometric Drills

-

- Box Jumps: Jump onto a box or platform and then step down (it’s easier on your knees than jumping down). Do 3-5 sets of 3-6 jumps.

-

- Depth Jumps: Jump off a box and immediately jump as high as you can when you hit the ground. Do 3-5 sets of 3-5 jumps.

- Broad Jumps: Jump forward as far as you can from a standing position. Do 3-5 sets of 3-6 jumps.

Explosive Movements

-

- Power Cleans: Lift a weight from the ground in a deadlift position to your shoulders in one quick motion. Do 3 sets of 4-6 reps.

-

- Medicine Ball Slams: Lift a heavy ball above your head and slam it down to the ground. Do 3 sets of 10-15 slams.

- Vertical Leap Practice: Stand still and jump as high as you can, trying to reach a target above you. Do 3 sets of 8-10 jumps.

Volleyball-Specific Jump Drills

One of the best ways to get better at something is to actually do that thing.

Sport-specific drills breakdown the movements you do in a game into single exercises, which lets you work on technique and skill over-and-over again:

-

- Approach Jumps: Practice your approach and jump as if you are going to spike the ball. Do 3 sets of 8-10 jumps.

-

- Block Jumps: Jump up as if you are blocking a shot at the net. Do 3 sets of 8-10 jumps.

- Spike Jumps: Practice jumping and hitting the ball at the highest point you can reach. Do 3 sets of 8-10 jumps.

You can add someone setting you up with a ball for these too to get even more specific.

I still like to do these without a ball so that the focus is 100% on the technique, and then adding the ball once my athletes are comfortable with their form.

Recovery & Injury Prevention

Rest is just as important as exercise.

Make sure to take rest days to let your muscles grow.

Active recovery, like light jogging or swimming, can also help by taking away from the stresses of volleyball training or playing.

It can’t be overstated how important rest is—without it, you’ll never reach your jumping potential.

That’s why using a dedicated jump training program can really help, as it takes all the thinking out of it for you.

Using the Skyhook Contact Mat for Jump Training

Adding the Skyhook Contact Mat to your jump training exercises can take your vertical jump to the next level.

This high-tech mat measures the height of your jumps with a ton of accuracy, giving you instant feedback on your performance.

Here’s how you can use it:

-

- Track Your Progress: You can monitor your jump height over time. Set goals and watch as your vertical jump improves with each training session.

-

- Motivation and Competition: Knowing your exact jump height can be a great motivator. You can challenge yourself to jump higher each time or even compete with teammates to see who can reach the highest.

-

- Technique Improvement: The mat helps you analyze your jumping technique. By seeing how high you jump, along with the many other factors it measures, you can make adjustments to your form and technique to maximize your height.

- Integration with Exercises: Use the mat during your plyometric and sport-specific drills. For example, do box jumps or approach jumps on the mat to get accurate measurements and immediate feedback.

Conclusion

Jumping higher can make you a better volleyball player and give you that competitive edge.

By following these exercises and tips, you can improve your vertical jump, and you can always build off of these suggestions.

Start adding these drills to your routine and watch your jump height soar—happy training!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF