Imagine you just finished writing the perfect workout plan for a day of practice. You know it’s going to be a great day on the track. The athletes are focused intently during the warm-up—it’s go time and they are ready. Suddenly, right as you are wrapping up the warm-up, a popup thunderstorm rolls in and lightning strikes in the area.

You are forced to move inside for safety.

What’s next? Do you find something for the athletes to do to stay warm and hope it’s only a 30-minute delay? Do you scrap your perfect workout plans and cancel practice all together? Or do you try to pull off a substitute workout?

We’ve all been in a similar situation before. Maybe it’s not a thunderstorm that throws off practice, but an athlete shows up too sore or with a nagging injury that prevents them from doing what you had planned for the day. Understanding that consistency in training is both a key to long-term improvement as well as a part of maintaining training loads for injury prevention, being good at Plan B training is a skill all coaches need to master.

Hierarchies and Goals in a Plan B Session

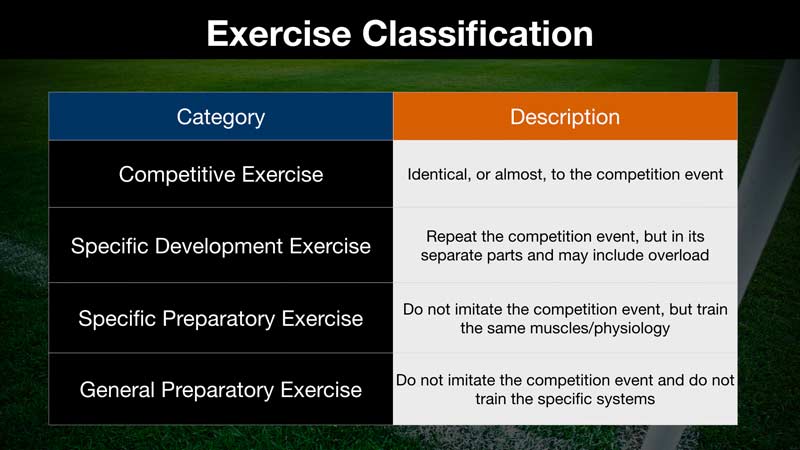

The first step in mastering Plan B training is understanding the idea of exercise classifications. The most popular exercise classification system is probably from Dr. Anatoliy Bondarchuck’s work.

At the top level of the hierarchy is the Competitive Event or exercise itself. For our track coaches, an example could be a 60-meter dash, full approach long jump, 400-meter dash, a full throw, or in the case of practice, whatever the original workout plan is.

One level below that, exists second-generation or Specific Development Exercises, which are exercises that consist of a slightly broken-down part of the full event. This could be short approach jumps for a long jumper, stand throws for a thrower, 30-meter flys for a sprinter, etc. These exercises still resemble the full event but are slightly scaled back or modified.

The next level down, third-generation or Specific Preparatory Exercises, are things that support the development of the first-generation (the Competitive Event itself) and second-generation exercises. For a jumper, this might be standing jumps into the pit or accelerations. For sprinters, it might be short accelerations or skipping/plyometric/bounding exercises. For throwers, it might be Olympic lifting or maximal strength training.

The last level, fourth-generation or General Preparatory Exercises, are exercises that do not always look like the competitive event and do not directly train the specific muscles or energy system in the same manner as the competitive event, but might be used for general health, coordination, general capacity, or active recovery. Depending on the time of the year, use of General Preparatory Exercises are cautioned, as they may actually lead to a de-training of specific event qualities.

Applying Exercise Classifications to Plan B Training

The goal of Plan B training is to find something that mimics the planned workout of the day as closely as possible in terms of both biomechanical and energy system similarity. Think in terms of movement vectors (horizontal, vertical), force production (maximal, elastic), work-to-rest ratios, and muscles involved. When using the exercise classification system in plan B training, it is important to understand that the original workout would be considered “The Competitive Event.” You then work down through the classifications as your constraints allow you to apply the next-best stimulus.

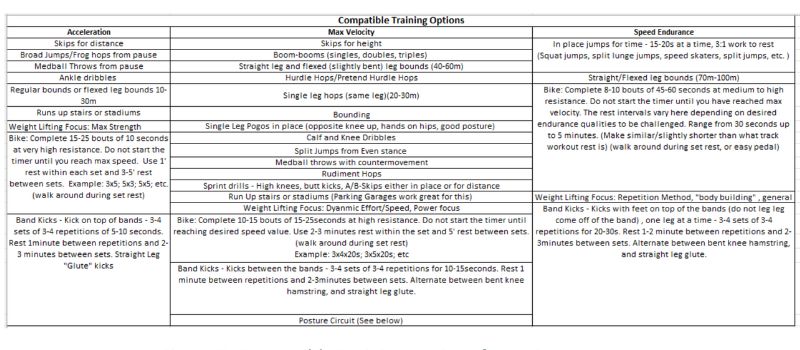

The goal of Plan B training is to find something that mimics the planned workout of the day as closely as possible, says @coachjonhughes. Share on XI challenge coaches to make a list of exercises, drills, lifts, etc. that fit within each of the levels for their specific event they are coaching or for their commonly prescribed workouts. For speed and power competitive events, many of the specific preparatory exercises and general preparatory exercises will begin to overlap. For example, coaches can create a chart like the one below. I’ve linked to this chart to be used as a “living document”—feel free to add to it or make a copy for yourself to add to and organize in a way that makes sense to you.

Figure 2. Compatible Training Options for Sprinters

Real World Application

Assume you have planned the following workout for an acceleration day workout:

- Three 10-meter blocks

- Three 20-meter blocks

- Three 30-meter blocks

An athlete shows up and has a tight hamstring and they do not feel comfortable going at full speed for fear of risking an injury. They get through the warm-up pain-free, with only minor levels of discomfort. You agree that doing the workout as written is probably not the best idea, but you want them to get some work in so they don’t have training gaps when they return to the full training process. You must ask yourself: “how can I modify this workout to still get a similar training effect without the same high risk of injury?”

You must ask yourself: how can I modify this workout to still get a similar training effect without the same high risk of injury?, says @coachjonhughes. Share on XThis is where the classification of exercises comes into play. As stated earlier, your planned workout (in this example, block starts), is now considered your “Competitive Event.” Move down the classification system to “Special Development Exercises” and find substitute exercises.

First, you could modify intensity by removing spikes, by taking away the blocks and going from a standing start, or even going from a skip-in or walk-in start. Each regression would be considered a specific development exercise for block starts, giving the athlete a similar training effect while limiting the intensity. Both the walk-in and skip-in starts eliminate the amount of strength and power needed to overcome inertia and also decreases the amount of technical skill and thereby the mental load by not needing to go from a full four-point start. You could also reduce the distance of the accelerations. By limiting the distance, you will limit the speed the athlete attains, most likely reducing the likelihood of injury.

If you feel that these options are still too risky or the athlete does not feel comfortable with them, move down one more generation or classification to “Specific Preparatory Exercises.” Look at the biomechanics of acceleration to try to match force vectors, shapes, and types of force output. Since an acceleration is more horizontally force directed, maybe you choose a skip for distance instead of doing any actual accelerations. Skips will limit the top speed of the athlete and possibly reduce some range of motion, which will help reduce the possibility of injury, but you are still choosing an explosive movement that matches the same force vectors as an acceleration.

If the skips or other exercise you think of that fall under “Specific Preparatory Exercises” still cause the athlete discomfort, you could choose broad jumps or standing triple jumps. These also have a horizontal force component and involve overcoming inertia, which is similar to the first steps in a block start. Medicine ball power throws could also be implemented. I would have the athlete start the throw from a static position without a countermovement. This will more closely resemble the initial push out of the blocks rather than doing a throw with a countermovement or momentum involved.

Since the original workout involved repetitions to 30 meters, you could also include a few sets of exercises that resemble maximal speed sprinting. Depending on the level of the athlete, 30 meters will allow them to achieve a high percentage of top speed. Here you might implement skips for height, which involve a more vertical force vector similar to maximal sprinting. If you switch to jumps or medicine ball throws—do them with a countermovement to activate the stretch-reflex and involve momentum.

Lastly, if these exercises are still deemed too risky, maybe you drop down one more level to “General Preparatory Exercises” and switch to a bike. By using a bike, you can still try to mimic the work-to-rest ratios of the workout, so the athlete does not lose any specific fitness. When transferring a workout to the bike, you want to try the best you can to match similar work-to-rest ratios and force outputs. For an acceleration-themed workout, you would want to use extremely high levels of resistance on the bike to match the high strength outputs required from acceleration. An example acceleration-themed bike workout is below:

- Three to five sets of three repetitions of 7-10 seconds with VERY HIGH resistance.

- Use 60-90 seconds of recovery between the repetitions and 3-5 minutes of rest between the sets (similar to what you would have been having the athlete use if they were on the track).

Let’s look at a full example of what you might have come up with for the modified plan B training session. (Options are only limited by what you can come up with, how the athlete tolerates each exercise, and what your other external constraints are. There is no perfect plan B session that is all-encompassing or “one-size fits all.”)

- Three sets of three broad jumps starting from a paused, static start (90-second set rest).

- Two sets of three underhand forward medicine ball throws, from a paused, static start (90-second set rest).

- Three 20-meter skips for distance (walk back recovery).

- Three 20-meter skips for height (walk back recovery).

- Three 30-meter dribble progressions (10 meters over the ankle, 10 meters over the calf, and 10 meters over the knee) (walk back recovery).

With the workout above you have accomplished several things.

- Between exercises one and two, the athlete has performed 15 reps of explosive “starts,” overcoming inertia like the first push out of the blocks. (Since these will not be as taxing as a full block start, I increase the volume slightly compared to the nine in the original workout.)

- The athlete achieved 210 meters of volume of skips and dribbles with similar work-to-rest ratios and force vectors of what would have occurred during the original workout. (Again, this is slightly more volume than the original workout since the intensity is lower.)

- You have most likely relieved some mental stress that the athlete would have accumulated from missing a training session altogether and helped keep their confidence high.

- You’ve helped eliminate a training gap within the return to play process and maintained some acute training load for the day.

Implementing Your Plan Bs

This identical process can be used not just for athletes that are not at 100% for the day, but also for days when the weather cancels your plans or you are constrained by facilities, space limitations, etc.

My advice is to sit down and make a list of exercises you know and classify them based on the classification system used above. Once you have a large list, organize them further into specific regressions and progressions, or group them based on your common daily training themes. Use the chart I provided as a starting point and organize it in a way that makes sense to you. I encourage you to share it with others for feedback, improvement, and the possibility of learning more.

Once you understand this framework and begin to implement Plan B training when needed, it will become easier and easier to adjust on the fly in practice when interruptions arise, says @coachjonhughes. Share on XOnce you understand this framework and begin to implement Plan B training when needed, it will become easier and easier to adjust on the fly in practice when interruptions arise. The better you are as a coach at programming Plan B work, the faster the athletes you work with will return from injury, and the better the athletes you work with will progress due to the reduction of missed training time that may result when plans are scrapped with no alternative work prescribed.

Let me know your thoughts and feedback on this approach to Plan B training (and share your exercise classifications) on X (formerly Twitter): @coachjonhughes.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF