The hex bar deadlift is a primary strength exercise in athletic fitness programs from middle school to college, and hex bar jumps have become popular for improving explosiveness. The hex bar also has many advantages over dumbbells. That said, there are a few downsides to using this unique bar too often, particularly with maximum weights.

I have a unique perspective on the pros and cons of hex bar training because I worked at Bigger Faster Stronger (BFS). BFS introduced the hex bar to the strength coaching community and promoted the hex bar deadlift for nearly four decades through their magazine and clinics.

BFS introduced the hex bar to the strength coaching community and promoted the hex bar deadlift for nearly four decades through their magazine and clinics. Share on XBefore the hex bar, BFS championed the straight bar deadlift as a core lower-body exercise for athletic performance. Their weekly program design for their core lifts was organized as follows:

Monday Wednesday Friday

Box Squat Power Clean Back Squat

Towel Bench Press Deadlift Bench Press

The downside of this program was that BFS found that athletes often rounded their lower back when deadlifting maximum loads, increasing the risk of injury. As a precaution, they said athletes should recruit a spotter during their heaviest sets to protect the spine (yes, you can spot a deadlift).

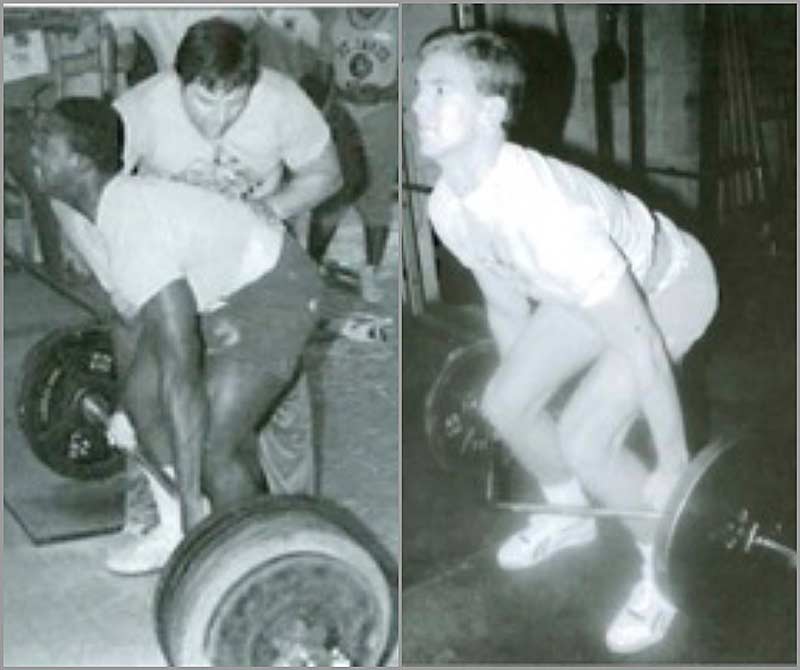

Spotting a deadlift involves having a spotter place one arm across the athlete’s chest and the other on the lower back. If the spotter felt the athlete’s lower back rounding during the lift, they would tell them to drop the bar. BFS coaches demonstrated this spotting technique at their clinics, often with participants attempting maximal weights.

Of course, we’re talking about 40+ years ago, and this hands-on spotting technique would not fly in today’s strength coaching environment. That is why BFS was excited to discover the trap bar in the early 80s.

Enter the Trap Bar

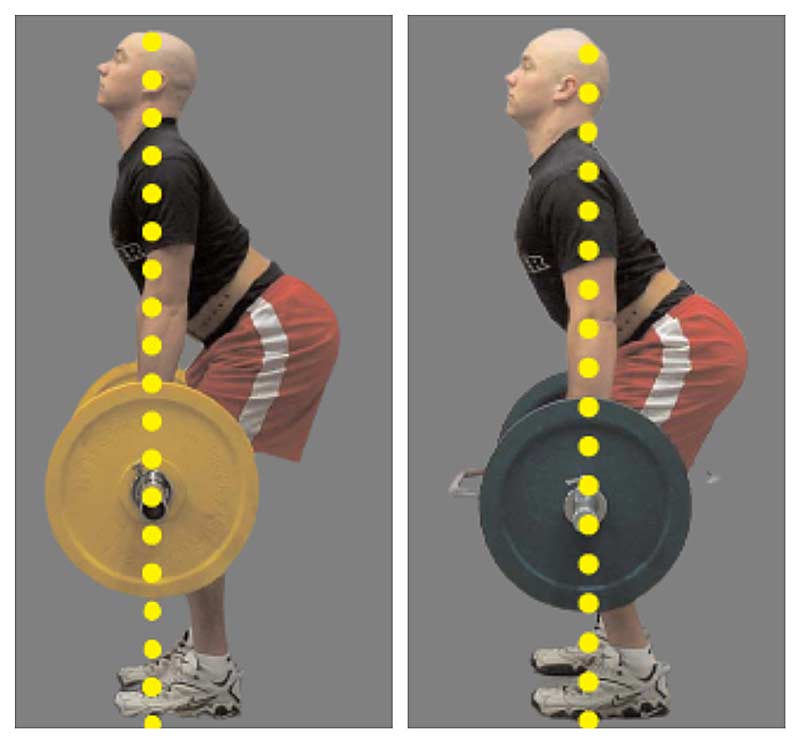

The trap bar was introduced to the Iron Game in 1986 by Al Gerard, a powerlifter with a history of lower back pain. To continue training heavy, Gerard developed a four-sided barbell that looked like two triangles arranged base to base, which he called the trap bar. Gerard would step inside the bar, grasping the handles with his hands at his sides rather than in front. This design put the bar’s center of mass (COM) in line with his body’s COM throughout the entire lift.

Gerard found that the triangle design of the trap bar enabled him to lift the bar with a more upright stance. This postural change shifted the stress away from his lower back and hamstring muscles and onto his quads. And unlike a sumo deadlift that requires a wide foot stance, a hip- or shoulder-width stance could be used with a trap bar.

It’s challenging for many beginners to assume the optimal starting position on a deadlift. At the start of a conventional deadlift, the lower back should have a slight arch to shift the stress from the disks to the muscles and connective tissues. With your hands at your sides, the shoulders are pulled back, making it easier to arch the lower back.

BFS found that the trap bar also helped athletes lift more weight in the squat, but not so much from a physical standpoint. Bob Rowbotham, the CEO of BFS, says lifting heavy loads with the trap bar gives athletes the confidence to try heavier weights in the back squat. For example, if an athlete can back squat 200 pounds and works up to a 300-pound trap bar deadlift, they will have more confidence when attempting a back squat of 205 pounds or more.

The trap bar was a great idea—the hex bar was even better.

BFS found that a trap bar easily tipped backward and forward and didn’t provide enough legroom for larger athletes—note how cramped the basketball player is in Image 1. This later point was particularly important to BFS because, at the time, their coaches were working with the Utah Jazz.

One solution was a hexagonal (six-sided) design. This design didn’t tilt as easily and offered considerably more legroom. The hex bar was an immediate hit with athletes, especially football players at the high school level. Strength coaches and PE instructors preferred the hex bar deadlift over the straight bar deadlift because it was easier to master and students were less likely to round their lower back.

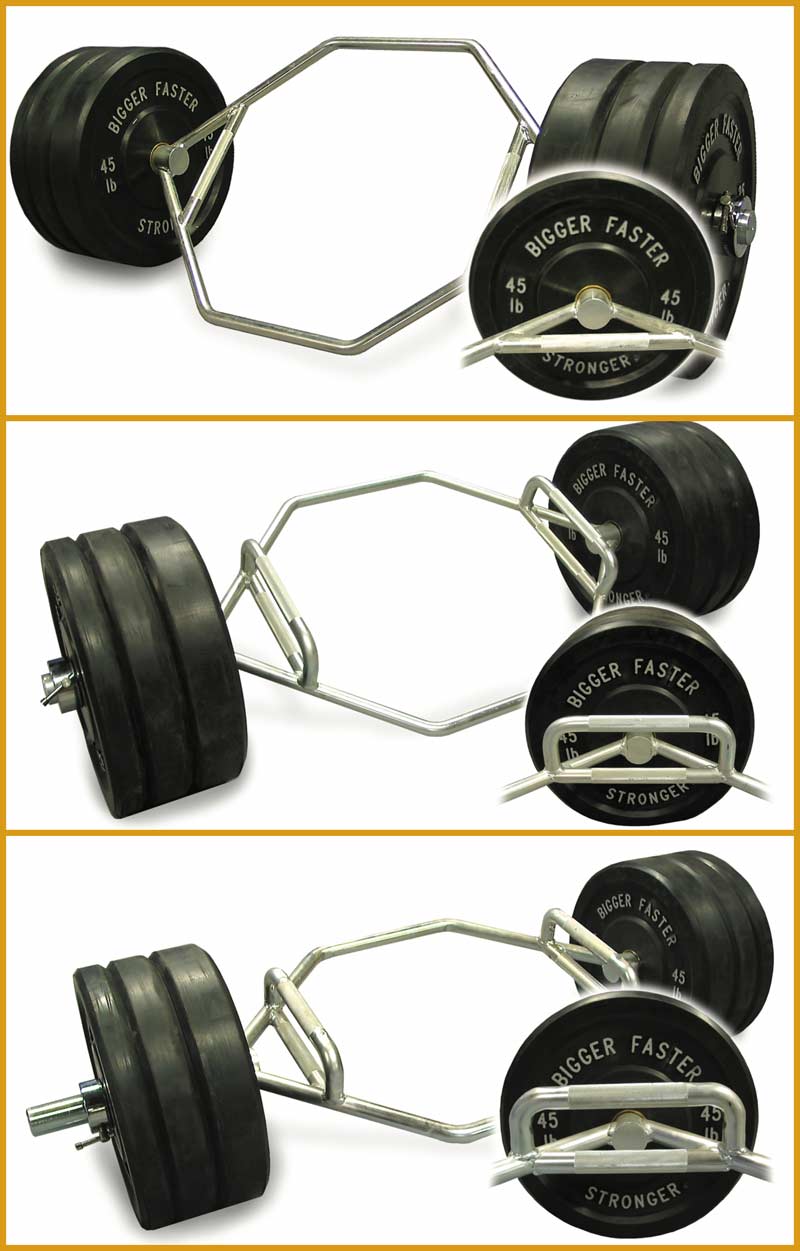

As more athletes used the hex bar, BFS saw a need to develop several other types of hex bars. One popular version was a “combo” hex bar with regular handles as well as high handles to accommodate taller athletes so they didn’t have to bend down so far. This bar was followed by a heavy duty, 75-pound “Mega” hex bar. This bar had thicker, raised handles and longer sleeves that could hold considerably more weight for stronger athletes. But the evolution of the hex bar didn’t stop there.

Other equipment manufacturers caught on and began producing unique hex bars, such as one with an open-back design. Several equipment companies designed hex bars with rotating handles that offer different grips, and now there are even larger units than the Mega hex bar. BFS also saw the need for a 15-pound aluminum bar, which was suitable for children and for beginners performing hex bar jumps.

Before going further, let’s see if all this attention to the hex bar is deserved by reviewing some research.

The Science of Hex Bars

The increasing popularity of hex bars captured the attention of sports scientists who wanted to verify that the bar did what its proponents claimed. Let’s start with the belief that hex bar deadlifts produce less stress on the spine than straight bar deadlifts.

One study that compared the straight bar deadlift to the hex bar deadlift was published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. The authors found that the hex bar “significantly increased the peak movement at the knee and significantly decreased the peak movement at the lumbar spine and hip compared to the deadlifts performed with the straight barbell.” To use the popular terminology, the hex bar deadlift would be considered a “quad-dominant” exercise, and the straight bar deadlift would be a “hip-dominant” exercise.

To use the popular terminology, the hex bar deadlift would be considered a “quad-dominant” exercise, and the straight bar deadlift would be a “hip-dominant” exercise. Share on X

As for the value of hex bar jumps for developing explosiveness, another JSCR study found that vertical jumps performed with a hex bar were superior to vertical jumping with a straight bar on your shoulders. The researchers concluded, “The results of the present study demonstrate that if the resistance is moved from the shoulder to arms’ length using a hexagonal barbell, the athlete can jump higher and generate greater force, power, velocity and rate of force development.”

One reason the hex bar may be superior to barbell squat jumps is that the upper body is more involved with a hex bar jump. The shoulders can shrug while jumping with a hex bar, whereas the shoulders are motionless during a barbell jump. (You can prove the contribution of the upper body by jumping off a contact mat with your hands on your hips and then using your arms—you should be able to jump several inches higher when using your arms.)

Moving on, the researchers said, “The continuous frame of the hexagonal barbell will provide several advantages over dumbbells, including improved stability and greater capacity to apply a wider range of loads.” I would add that jumping with dumbbells is an excellent way to develop nasty bruises on your thighs.

Hex bar deadlifts and hex bar jumps are two of the most popular exercises performed with hex bars, but there are many other uses for these bars. Here are six of them:

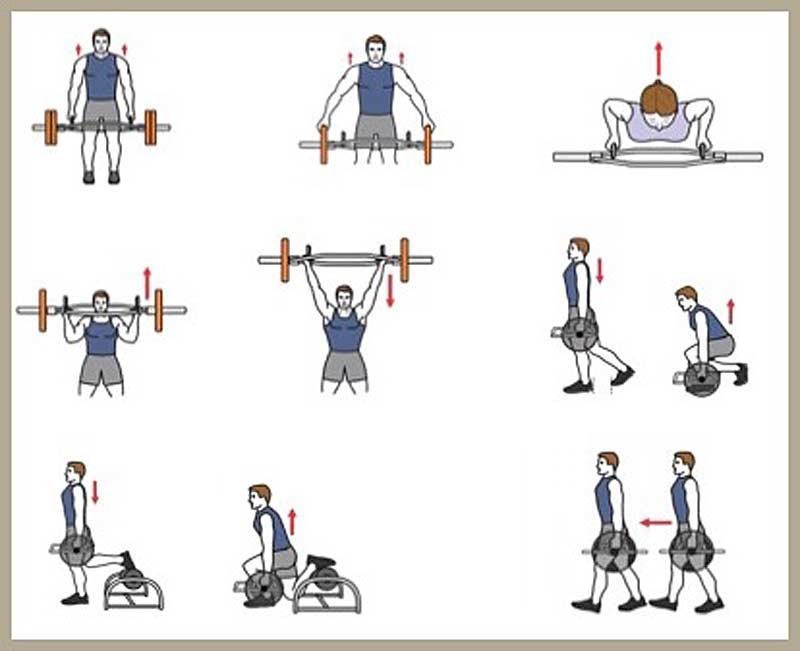

1. Shoulder Shrugs. Having your arms positioned at your sides enables you to raise them higher than with a straight bar. To save time, BFS recommends that after the last rep of a set of deadlifts, while still erect, finish off with a few shoulder shrugs.

Another shrug variation, made popular by Mr. America Steve “Hercules” Reeves, involves grasping the inside plates rather than the handles. This “pinch grip” technique would be valuable for wrestlers and other athletes who need a strong grip. For more on shoulder shrugs, check out Kelso’s Shrug Book, a classic by Paul Kelso published in 1992.

Hex bar shoulder shrugs with a “pinch grip” technique would be valuable for wrestlers and other athletes who need a strong grip. Share on X2. Push-ups. The push-up has been criticized for placing excessive stress on the wrists. This variation is performed with a high-handled hex bar. These handles allow the wrist to be aligned with the forearms, reducing the stress on the wrists; this is better than using many types of dumbbells, which can move. As a bonus, the high handles allow for a greater range of motion.

3. “W” Overhead Press. Paul Gagné, a Canadian strength coach and Posturologist, taught me this exercise. A neutral grip (palms facing each other) is considered easier on the shoulders than the pronated grip used in a military press. It is also more stable than dumbbells, increasing the amount of weight you can use. However, the setup is tricky with heavier weights; it’s best to rest the bar inside a power rack and step under it.

4. Split Squat. Open-back hex bars are ideal for split squats, including rear-leg-elevated split squats. It can be awkward to perform this exercise with dumbbells because you must bend down low to pick them up. The hex bar enables heavier weights to be used because it’s more stable than dumbbells and you can pick up the weights from a higher height.

5. Rear-Leg-Elevated Split Squats. I have issues with today’s strength coaching love affair with rear-leg elevated split squats (see my article on Bulgarian lunges). If you’re going to do them, an open-back hex bar is the way to go. As with the regular split squats, you can pick up the weight from a higher height than dumbbells and the hex bar is more stable.

6. Farmer’s Walk. For strength coaches on a budget, the parallel grips for the hex bar provide a suitable substitute for farmer’s walk devices. Yes, dumbbells can be used for the farmer’s walk and offer a parallel hand position, but there is a higher risk of dropping the weight plates on your toes if you lose your grip. There is also the issue of bruising, as the dumbbell plates can bang against the thighs.

For strength coaches on a budget, the parallel grips for the hex bar provide a suitable substitute for farmer’s walk devices. Share on XA high-handled hex bar is best for this exercise because these handles don’t require you to bend down as far to assume the starting position. However, the issue with conventional hex bars is that you must take relatively small steps; an open-back hex bar allows for a longer stride.

Those variations should add valuable tools to your weight training toolbox, and many other exercises can be performed with these bars.

Those are the pros of hex bars—let’s look at some cons.

The Dark Side of Hex Bars

Now that I’ve got you excited about the versatility and benefits of the hex bar, let’s look at seven special considerations to think about when using the hex bar.

1. Compressive Forces. I saw a relatively short male athlete using the high handles on a combo hex bar while standing on thick bumper plates. Perplexed, I asked him what he was doing. He told me that he wanted to perform the exercise through a greater range of motion. Although this athlete had performed hex bar deadlifts in high school, he didn’t realize he could flip the bar over and use the lower handles!

I share this story because high hex bar handles were originally designed for tall athletes to make hex bar deadlifts more comfortable. However, many strength coaches only have their athletes use the high handles because their athletes can lift more weight (and their video clips look cool on Instagram). I saw a female athlete doing a high hex bar deadlift for the first time a few years ago. Although her best squat was 160 pounds, she deadlifted 285 pounds!

The point is that using high hex bar handles rather than the standard handles enables athletes of average height to use significantly heavier weights, placing higher compressive forces on the spine. An occasional max-out day with a high hex bar may be fine, but you may be asking for trouble if you are of average height and max out too frequently. My colleague Paul Gagné shares my opinion.

An occasional max-out day with a high hex bar may be fine, but you may be asking for trouble if you are of average height and max out too frequently. Share on XGagné has trained over 500 NHL players. For many of those athletes, he had to be conservative with the hex bar deadlift as he found these compressive forces often led to hip impingement. When you are coaching athletes competing on the professional level, you must take a serious look at the risks vs. rewards of any weight training exercise.

2. Instability. Because the hands are held away from the body, the hex bar is less stable at the top of the lift compared to a conventional deadlift. This instability could cause adverse shearing forces on the spine. The problem is compounded because much heavier weights can be lifted than with a straight bar, and it’s worse when using bands.

Strength coaches often have their athletes use elastic bands when performing hex bar deadlifts. This is usually accomplished by attaching the ends of the bands to the outside sleeves, then having the athlete step on the band as they lift. The result is that as the athlete lifts the bar and the band stretches, the resistance curve increases to match the strength curve of the athlete. The issue is that bands further increase the instability of the exercise.

3. Specificity. The hex bar deadlift has little carryover to weightlifting pulling movements such as the clean, power clean, snatch, or power snatch. With the Olympic lifts, during the first part of the pull, the bar shifts from a position in front of the body’s COM to a position aligned with its COM. The hex bar starts with the resistance aligned with the COM and remains there throughout the entire lift. Besides the differences in muscle development, the pulling motion can adversely affect the biomechanics of the Olympic lifts.

4. Cheating. Bouncing the bar off the floor during hex bar deadlifts enables larger loads to be used but creates harmful stress on the spine, especially if the plates land unevenly. Instead, a relatively slow “touch-and-go” technique should be used.

5. ACL Stress. With normal-sized athletes, high hex bar handles reduce the range of motion of the legs, such that the knees are in a position that applies the highest stress to the ACL.

ACL injuries are among the most common and severe to female athletes, affecting them as much as five times more than male athletes in several sports. Athletes recovering from an ACL injury, or those involved in sports with a high risk of ACL injury, may need to take a more conservative approach to programming the high hex bar in their workouts.

6. Plyometric Effect. Because the hex bar deadlift does not begin with an eccentric contraction, there is no stretch-shortening cycle (i.e., plyometric effect) that helps develop explosiveness. Can this exercise make the athlete stronger? Sure, but it will do little to improve explosiveness. Hex bar jumps are a better alternative if explosiveness is a primary goal.

7. Flexibility Restrictions. The hex bar does not allow the legs to work through a full range of motion. Performing only partial-range leg exercises reduces the muscle-building effect and may increase an athlete’s susceptibility to knee, ankle, and Achilles injuries. (For more on this subject, see my article.)

The hex bar has many advantages over the straight bar and dumbbells for developing strength and explosiveness. But if the hex bar is misused or if maximal loads are used too frequently with high-handled hex bars, you may be doing more harm than good. The bottom line with the hex bar is that it’s not only a matter of training heavier but training smarter!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Swinton, Paul A; Stewart, Arthur; Agouris, Ioannis; Keogh, Justin WL; and Lloyd, Ray. “A Biomechanical Analysis of Straight and Hexagonal Barbell Deadlifts Using Submaximal Loads.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 25(7); pp 2000-9, July 2011.

Swinton, Paul A; Stewart, Arthur D; Lloyd, Ray; Agouris, Ioannis; and Keogh, Justin WL. “Effect of Load Positioning on the Kinematics and Kinetics of Weighted Vertical Jumps.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(4); pp 906-913, April 2012.

Kelso, Paul. Kelso’s Shrug Book. Hats Off Books, Revised Edition, January 28, 2013.