[mashshare]

“If you don’t have the squat in your program, you don’t have a program!” has been a motto of Iron Game and strength-power athletes for the past half-century. In recent years, however, some strength coaches beg to differ. They contend that the “King of Exercises” is old school and should be replaced by a single-leg exercise called the Bulgarian lunge. Let me explain.

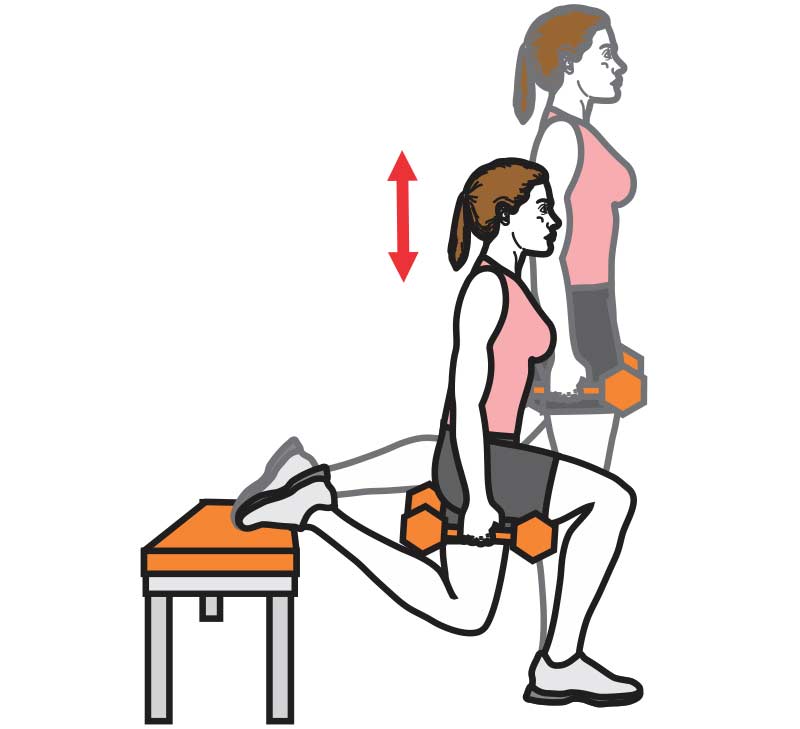

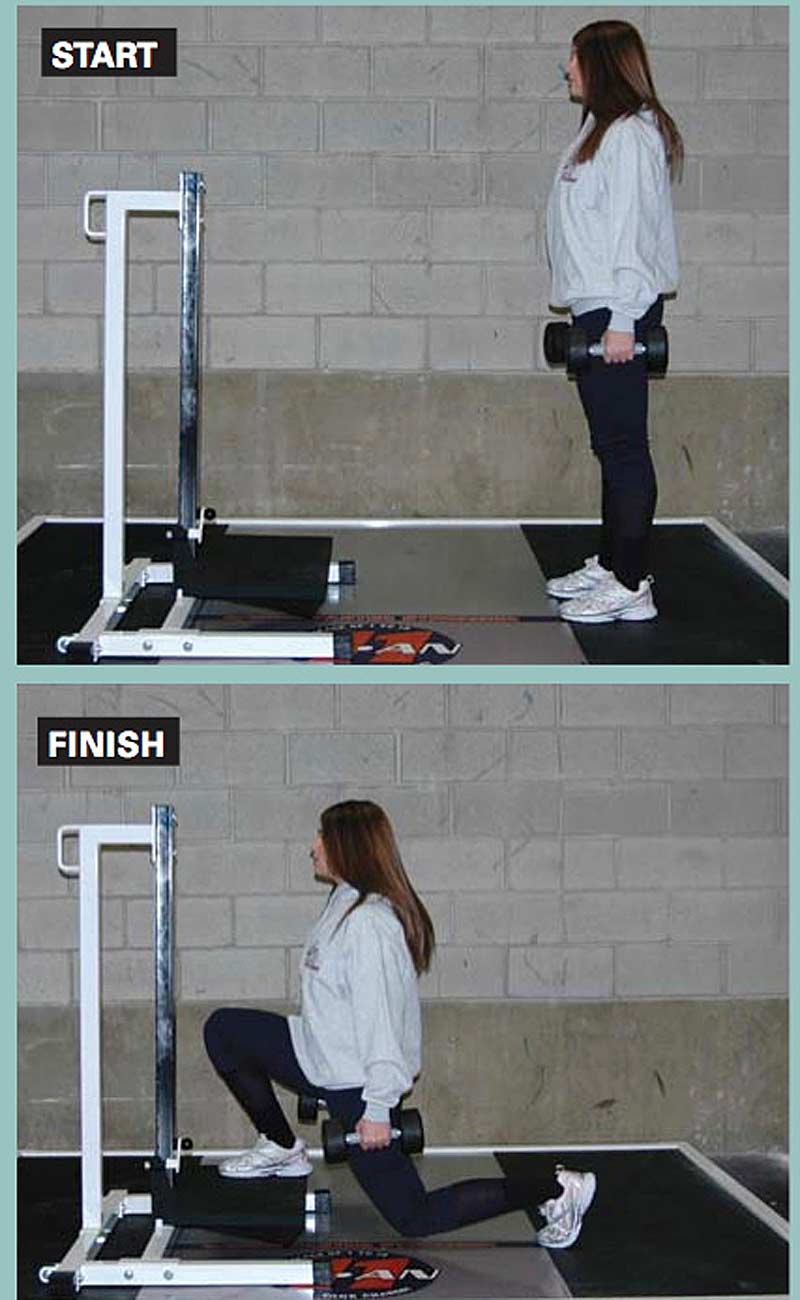

First, although the popular name of this single-leg exercise suggests that it’s a lunge, it’s actually a split squat. What’s the difference? With a lunge, you take a step, and your hips descend diagonally, like an escalator; with a split squat, your hips drop straight down, like an elevator. The name Bulgarian lunge has been used so often, however, that it stuck.

The History and Appeal of the Bulgarian Lunge

I began competitive weightlifting in 1972, a time when the two powerhouses of weightlifting were Russia (The Big Red Machine) and Bulgaria (The Little Country that Could). This was long before the Internet, so it was difficult to get credible information about how European weightlifters trained.

While there were articles written by Russian weightlifting coaches, they were looked upon with skepticism—why would the Russians share their training secrets? And there was the concern that the best coaches weren’t writing these articles because they were too busy coaching athletes. We even heard stories that Russian lifters amused themselves by performing bizarre exercises in the training halls at international competitions to see if the Americans would copy them. As for Bulgaria, the reports that their lifters were training five times a day and maxing out every day were a bit too hard to believe (and impractical, at that).

In 1989 our frustration came to an end, or so we thought, with the publication of an article in Muscle and Fitness entitled, “Bulgarian Leg Training Secrets.”

The article was written by weightlifting historian Dr. Terry Todd and Bulgarian weightlifting and strength coach Angel Spassov. Although Spassov was unknown to most American weightlifters, he was from Bulgaria, so he had insight into their training methods. Todd, in contrast, was an Iron Game celebrity.

As an athlete, Todd was the first man to officially squat 700 pounds, and his wife, Dr. Jan Todd, was the first woman to squat 500 pounds officially. As a PhD scholar, Todd was committed to preserving the history of the Iron Game and was instrumental in discrediting the myths about squats being harmful to the knees. He was also the driving force providing content for the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports at the University of Texas in Austin.

With those credentials, along with having an article published in a major newsstand magazine, there was little reason to doubt the accuracy of the article. At last, we were going to learn the secrets of the most powerful athletes in the world!

Bondarchuk, Verkhoshansky, and Transfer

Todd and Spassov’s article began by discussing the work of Anatoliy Bondarchuk. Bondarchuk won an Olympic gold medal in the hammer throw, coached a two-time Olympic gold medalist in the same event, and became a professor who wrote extensively about sports specific training. Unquestionably, Bondarchuk is a track and field legend.

According to Todd and Spassov, Bondarchuk did not believe the strength and power developed from the squat transferred well to sports. They said one of Bondarchuk’s arguments was that there is no sport other than weightlifting in which an athlete finds themselves in a full, rock-bottom squat.

Todd and Spassov also claimed that the stress put on the lower back from squats might not be worth the risk. How much stress? According to Bondarchuk, the compression forces on the lower back are at least doubled that of the weight from a standing position. Thus, an athlete who squatted 200 pounds would put 400 pounds of stress on the spine in the bottom position—considerably more when performing the lift quickly. Contrast this with a step-up, which is an exercise that most athletes would have difficulty doing using 50 percent of the weight they could use in squats.

Tackling the problem from another direction (literally), Russian track coach Professor Yuri Verkhoshansky tried using quarter squats with his jumpers. During the brutal winter months, his athletes had to train indoors, and heavy quarter squats seemed like a practical way to duplicate the stress on the body during the takeoffs for the jumps. Practical, yes—safe, probably not.

Because you can use considerably more weight in a quarter squat than a full squat, many of Verkhoshansky’s athletes complained of lower back pain from performing them. That’s the bad news. The good news is that this problem inspired Verkhoshansky to develop plyometrics, a valuable training method that seemed to help 12 of his athletes achieve the prestigious level of “Master of Sport.”

Soliciting the support of the bodybuilding community, Todd and Spassov strengthened their anti-squat propaganda with the following observation about single-leg training and leg development:

One thing coaches in the Soviet Union and Bulgaria noticed was that those athletes, both lifters and those in other sports, who dropped the squat and used the high step-up developed more complete muscularity than those who simply squatted. Many of the coaches say that the legs of those who work hard on the high step-up look more like those of someone who did sprinting and jumping as well as squatting. Apparently, the balance required in the high step-up calls more muscles into play, producing fuller, shapelier development.

Sports specificity, less injury risk, and a symmetrical physique—all valid reasons to consider adding single-leg movements to your workouts. But Todd and Spassov were not done and drove home their sales pitch with the following statement that shocked the weightlifting community:

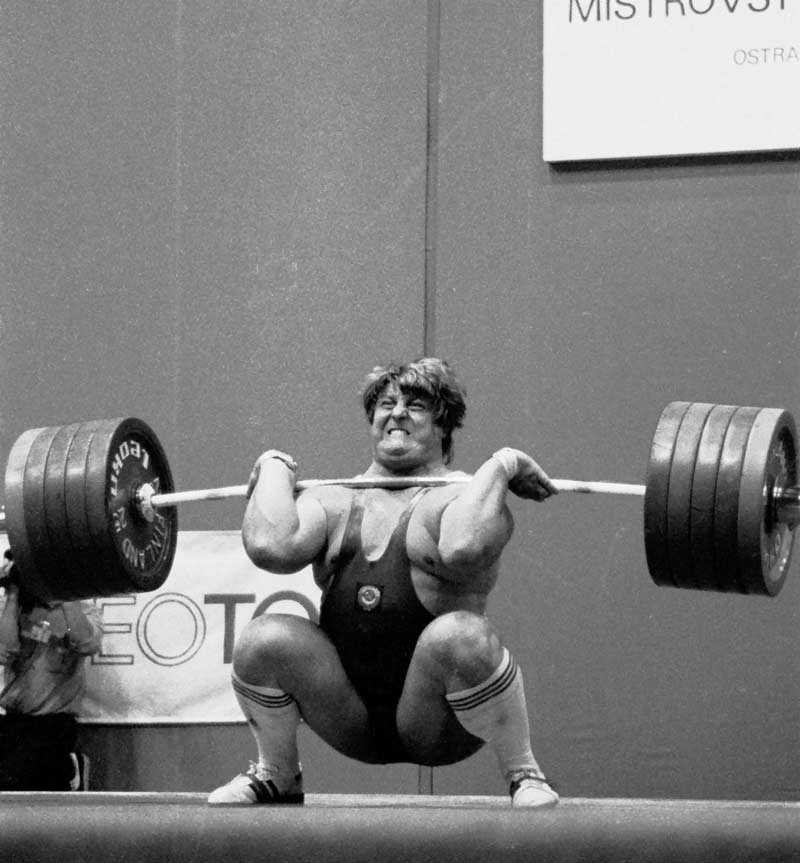

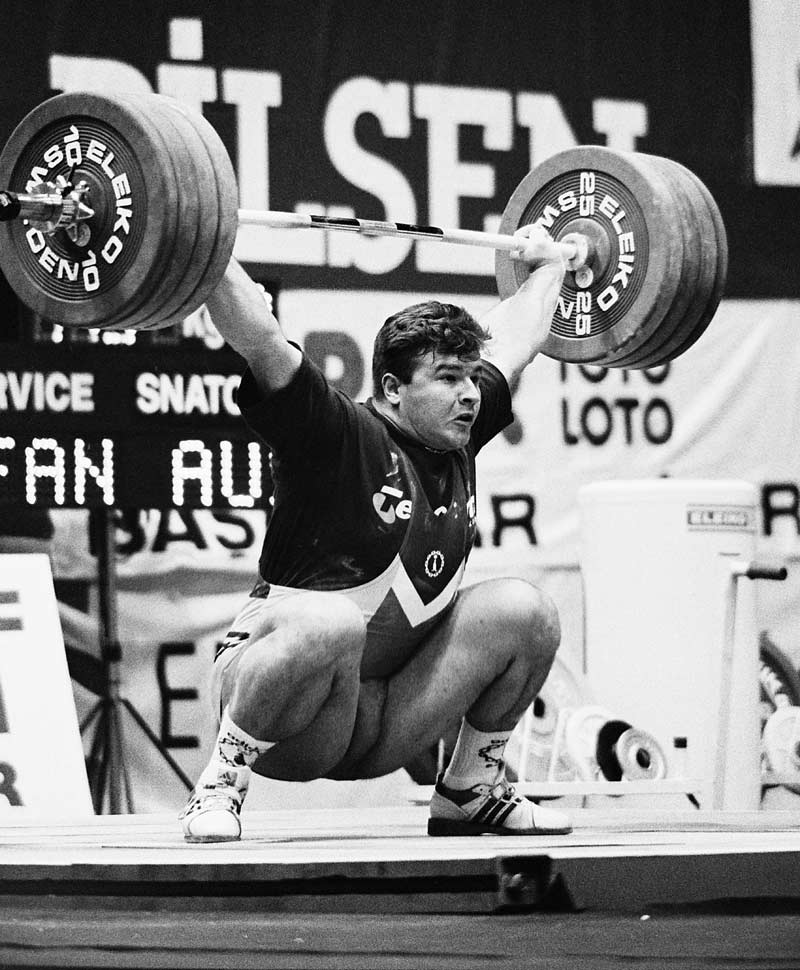

Several years ago the Bulgarian weightlifting team began to drop all back squatting in favor of high step-up. By that time, many Soviet lifters had abandoned squats and made their higher lifts in the snatch and clean and jerk than ever before.

They added that Leonid Taranenko, the absolute world record in the clean and jerk with 586 pounds, had not done a squat in over four years in favor of single-leg training!

Face to Face with Angel Spassov

After the publication of the article with Todd, Spassov came to the United States and continued championing the benefits of single-leg training. In addition to sharing his experience with Bulgarian weightlifters, Spassov talked about amazing feats of power performed by athletes who focused on single-leg training.

One of the athletes was 5’11” Khristo Markov, 1988 Olympic champion in the triple jump, who placed 42-inch high hurdles across the length of a soccer field. Jumping on one leg, touching just once between each hurdle, Markov could hop the entire distance of a soccer field, according to Spassov.

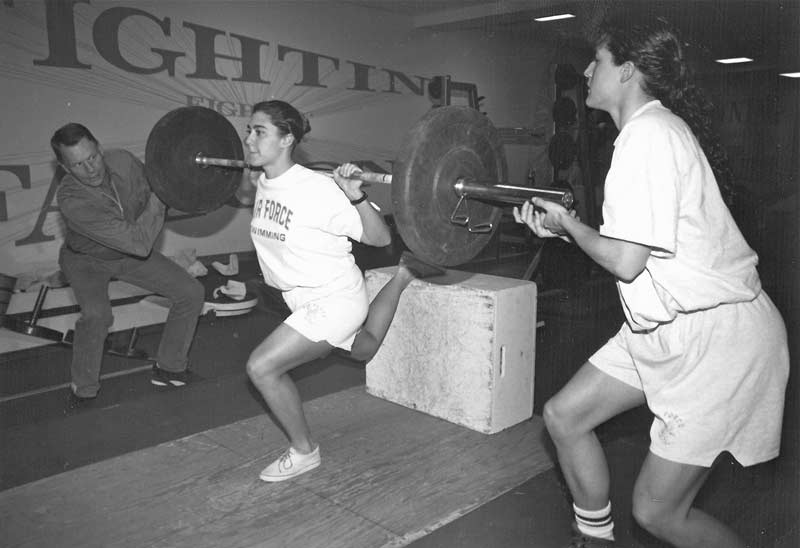

Around this time, Spassov was staying in Colorado, and I had the opportunity to visit him on several occasions. I also attended a presentation he gave in Denver. Since I was the primary person writing workouts for athletes at the Air Force Academy, I was able to try out these exercises on Division I college athletes.

The story could end there, but with my background in competitive weightlifting (and undergrad studies in journalism), I had a skeptical mindset and decided to investigate the idea that single-leg training with exercises such as the Bulgarian lunge or the high step-up are superior to squats.

The following seven points discuss the facts and fallacies surrounding single-leg training for weightlifters, especially regarding the Bulgarian lunge.

1. The Bulgarians Did Not Stop Doing Squats

In 2011, Ivan Abadjiev—the former head coach of the Bulgarian weightlifting team and creator of their training system—came to our educational center in Rhode Island to give a seminar. The following day I took the opportunity to ask him some questions in our gym while he trained one of his athletes.

I asked Abadjiev about the use of step-ups and lunges in his workouts, and he made it absolutely clear that his lifters never performed these two exercises. One of Abadjiev’s prize athletes was Stefan Botev, a weightlifting medalist in the 1992 and 1996 Olympic Games.

Iron Game journalist Randall J. Strossen, PhD asked Botev about step-ups:

Stefan Botev politely but firmly told me that I must have misunderstood something because Bulgarian weightlifters never did step-ups, but of course they squatted frequently and heavily—something I can attest to now, being lucky enough to have seen Bulgarian weightlifters training from Spokane to Sofia to Santo Domingo, and many points in between…Subsequent to my first talk with Botev about this, I confirmed this with Ivan Abadjiev, and the three of us have since laughed about this more than once.

Okay, here’s one more!

Dragomir Cioroslan is a Romanian weightlifting coach who trained under national team coach Ivan Abadjiev in his preparation for the 1984 Olympic Games. I spoke with him when he was coaching athletes at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Cioroslan told me the primary leg exercises for Bulgarian weightlifters were front squats and back squats and that he had never seen any lifters on the Bulgarian National Team perform single-leg exercises.

2. The Clean and Jerk World Record Holder Did Not Stop Doing Squats

After the Spassov and Todd article was published, sports scientist Bud Charniga was attending an international competition and asked Taranenko about his use of single-leg training. Taranenko said he had never talked to Spassov about his training and had recently squatted 837 pounds with a 2-second pause at the bottom. Taranenko did say, however, that he occasionally did step-ups when his lower back was overtrained.

3. The Bulgarian Lunge Is Frequently Taught Improperly

When I visited Spassov, one of his key points about the Bulgarian lunge was that the rear foot should only be elevated about 4-6 inches off the ground, with the ball of the foot on the platform. As such, the back leg is more actively involved in the exercise. In contrast, many functional trainers who promote this exercise teach that the rear foot should be pointed and elevated to approximately knee height, thus limiting the range of motion of the exercise.

I showed the Bulgarian lunge to Gorsha Sur, a Russian ice dancing champion whom I was coaching who won the US national championships with his partner Reneé Roca. Sur, who had clean and jerked 50 pounds over bodyweight, saw value in the exercise. However, he told me it would be better for ice dancers to elevate the rear foot to at least 12 inches and to hold the barbell on the front of the shoulders (as you would when performing a front squat) to encourage a tall posture.

I wrote about Sur’s variation in the international skating magazine Blades on Ice, and I called it the Gorsha Lunge to credit Sur. As an experiment, I tried this exercise once with several swimmers at the Air Force Academy, and the following day several of them came up to me and said, “Coach Goss, our Gorshas are sooooo sore!”

4. The Bulgarian Lunge Does Not Work the Legs Through a Full Range of Motion

One big selling point by those who promote Bulgarian lunges is that they provide a greater strength training effect than squats. Someone who can squat 200 pounds, for example, may be able to use 125 pounds on each leg with a Bulgarian lunge, and 125 + 125 = 250. More weight equals higher intensity, and higher intensity means the muscles are working harder. Well, you’d lift a lot more weight, too, if you only had to bend your knees halfway.

As another experiment, I had a 240-pound defensive lineman at the Air Force Academy do the exercise. After a few sessions, he did 505 pounds on each leg—not far off from what he was back squatting. His brother, who weighed about 200 pounds, did 400 pounds. I also had one female weightlifter who weighed 132 pounds do 205 pounds on each leg after a few training sessions. Again, don’t be too impressed—both legs are still working even when the rear foot is elevated and there’s only a partial movement.

When you perform partial-range exercises, the muscles around the knee are inadequately developed & the connective tissues lose their elasticity. Share on XSo what’s the big deal about, as they say in Game of Thrones, “bending the knee”? It’s important because, if you perform partial-range exercises, not only are the muscles around the knee inadequately developed but also the connective tissues lose their elasticity. Exercises with a partial range of motion adversely affect the elastic qualities of these tissues, and this could make those who focus on them more susceptible to injury.

A regular lunge offers more range of motion than the version with the back foot elevated. Many lifters in the 1950s and 1960s who were uncomfortable with the squat style of lifting used the split style; some achieved extremely low positions for the snatch and the clean. By the way, if you want to significantly increase the range of motion of the front leg during a lunge, perform it with the back foot on the ground, and the front foot elevated about 6-8 inches.

And this brings us to the next point.

5. The Bulgarian Lunge Should Be Performed in Conjunction with the Step-Up

Spassov made it clear to me that for training athletes, two single-leg exercises should be performed—the Bulgarian lunge and the step-up. He said the addition of the step-up ensured that the legs were worked through the full range of motion.

When Spassov moved to the United States, one of the first athletes he trained was weightlifter Ursula Garza, now Ursula Garza Papandrea. Spassov coached her for two and a half years. Papandrea told me that Spassov had her perform step-ups and split squats, but she did not stop squatting. Papandrea’s best results at a bodyweight of 123 pounds were a 330-pound back squat and a 286-pound front squat.

Papandrea’s results suggest Spassov believed that single-leg training for weightlifters should not replace squats but be performed in addition to them.

6. The Bulgarian Lunge Creates Unnatural Stresses on the Spine and Other Areas

One problem with the rear leg being too high in a Bulgarian lunge is that it puts the spine into hyperextension—and the more you bend your front leg, the greater the arch in the lower back. Performing it with a barbell across the back of your shoulders increases the stress as you have to stay more upright.

The stress is worse for those who already have an excessive degree of anterior (forward) pelvic tilt. For these individuals, excessive loading could result in injury to the rectus abdominus (i.e., the six-pack muscle), the muscles that flex the hip (such as the psoas), and may even cause a sports hernia. It gets worse.

Lifting the rear leg in a split squat can cause the pelvis to tilt and twist. Dr. Stuart McGill, one of the foremost experts on lower back pain with over 240 peer-reviewed scientific journal papers on lower back health to his credit, said that the Bulgarian lunge causes one side of the pelvis (ilium) to rotate forward and the other to rotate backward. According to McGill, excessively performing the Bulgarian lunge can cause “a laxity and you will actually start to compromise the connective tissue across the SI joint so that a minor motion, such as walking upstairs for example, now becomes painful.” This issue is especially problematic for those who play hockey and soccer.

One study looking at the risk of groin injuries in sports found that these injuries were common in many sports. The authors of the study noted, “In professional ice hockey and soccer players throughout the world, approximately 10% to 11% of all injuries are groin strains.” Is it possible that Bulgarian lunges could increase these numbers? Just ask Paul Gagne’.

Gagne’ is a posturologist and strength coach who has trained over 100 NHL players. Coach Gagne’ said that in his experience with these athletes, the Bulgarian lunge produces high levels of stress in the hip. He suggested that the internal rotation of the upper thigh bone (femur) during this lift may lead to injuries to the groin and knee. Ironically, many hockey strength coaches use Bulgarian lunges to help prevent injury when, in fact, the lunges may be contributing to them.

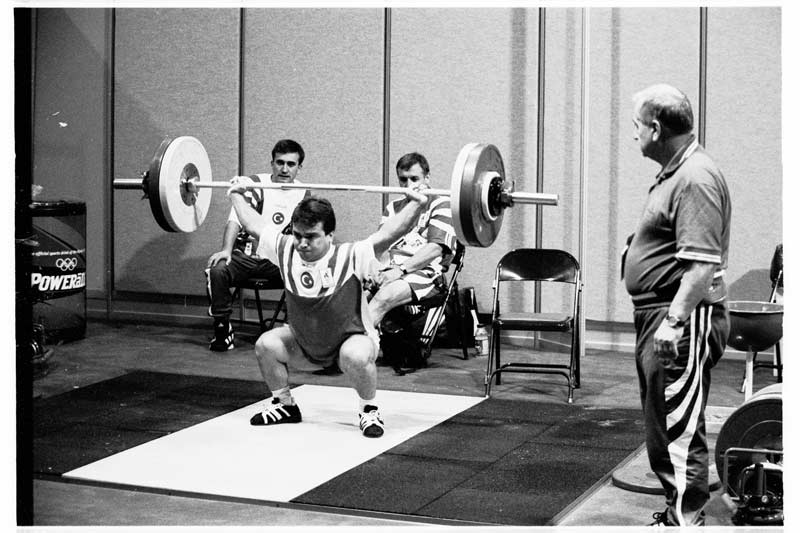

7. The Risk of Squats Hurting the Back Is Exaggerated

The data about the high compressive loads on the lumbar spine during deep squats may seem like cause for concern. And yes, going deeper in the squat increases the compressive forces on the spine—but the discs are most suited to deal with this method of loading as opposed to the twisting and hyperextension motions of the Bulgarian lunge. The bigger issue here, however, is that the strength coaches who over-promote the Bulgarian lunge are creating hyperbole about the risk of lower back injuries in Iron Game athletes who perform squats.

Strength coaches who over-promote the Bulgarian lunge create hyperbole about the risk of lower back injuries in Iron Game athletes who perform squats. Share on XIf squats were so bad, we would expect the sports of powerlifting and weightlifting to have a much higher injury risk than most other sports. One commonly used assessment to determine the safety of a sport is to look at the injury rate per 1,000 hours of athlete exposure.

In a study of 245 competitive and elite powerlifters, the injury rate was one injury per 1,000 hours of training. In another six-year study of elite male weightlifters training at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, the rate was 3.3 per 1,000 hours. These two studies looked at elite athletes who performed large volumes of training at high intensities. How do these numbers compare?

You would think that distance running and swimming would have much lower rates of injury than weightlifting and powerlifting. Not true. In one study, the numbers for distance runners were up to 12.1 injuries per 1,000 hours and up to 5.4 injuries per 1,000 hours for triathletes. Another study found that 95 percent of hockey players reported lumbar pain in their final year of practice. In American football, up to 30.9% of injuries involve the lumbar spine. And in baseball, 89.5% of players reported lower back pain during their career. You get the idea.

If we’re so concerned about injuries, should we condemn running, swimming, hockey, football, baseball, and continue down the list until we’re restricted to perhaps slow walking and sport stacking? My point here is that if you’re a strength coach and don’t like weightlifting and powerlifting, fine. But enough with the disinformation that the Bulgarian lunge is superior to the squat.

Final Thoughts

To sum up, let’s be more skeptical about so-called revolutionary athletic fitness training methods that focus on inferior exercises using light weights. Instead, stick to the basics and realize that not only do conventional strength training exercises have a lot to offer but also that it’s OK to be strong!

Header photo courtesy of Poliquin Group.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

Spassov, A., Todd, T. “Bulgarian Leg Training Secrets,”Overspeedtraining.com, Muscle and Fitness, Dec 1989.

Strossen, R. “Step-Ups for Weightlifters,”IronMind, Jan 2007.

Goss, K. “Step-Ups: Pros & Cons,”Bigger Faster Stronger, Spring 1991.

Goss, K. “Blades on Ice: The Gorsha Lunge,” Blades on Ice, Summer 1992.

McGill, S., Darby, K. “Dr. Stuart McGill and Kevin Darby on Split Squats and SI Joint Pain,” YouTube, Nov 2018.

Tyler, T., et al. “Groin Injuries in Sports Medicine.”Sports Health, May 2010.

Siewe, J., et al. “Injuries and Overuse Syndromes in Powerlifting,” International Journal of Sports Medicine, Jul 1999.

Calhoon, G., Fry, A. “Injury Rates and Profiles of Elite Competitive Weightlifters,” Journal of Athletic Training, Jul 1999.

van Mechelen, W. “Running Injuries: A Review of the Epidemiological Literature,” Sports Medicine, Nov 1992.

Korkia, P., et al. “An Epidemiological Investigation of Training and Injury Patterns in British Triathletes.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, Sep 1994.

Ball, J., et al., “Lumbar Spine Injuries in Sports: Review of the Literature and Current Treatment Recommendations,” Sports Medicine, Dec 2019.