Being in-season is, literally, what we all train for. The early mornings, the heavy squats, and the sweaty shirts are all needed to finally let the hard work pay off under the game day lights. Training has now shifted from the previous focus of grinding and building to maintaining and maybe even peaking. However, the foot is still down on the training gas pedal, but the workouts start to look and feel a little different. The priority is to keep the main thing the main thing in-season: being as physically and mentally ready as possible for games.

As training goals shift away from training itself, the amount of time dedicated to training usually shifts as well. This past year in the off-season, I was given 30 minutes three times a week to do “speed school” with my athletes (which just meant warm-up and speed training). Once the season started, I only had 10 minutes during practice and 15 minutes on game days for the warm-up and speed training—if I could fit it in. This isn’t right or wrong; it just is what it is and reflects the training priorities of being in-season.

Athletes’ speed in-season is important because speed has the shortest training residual of all the training adaptations. For example, speed has a 5 ± 3 day “use it or lose it” timeline (basically a week) whereas strength has a 30 ± 5 day timelines (basically a month) (Issurin, 2008). This means at least once a week you need to hit 95+% of your fastest sprint speed to stimulate and maintain it, and maybe even make speed gains. Yes, it’d be fair to assume that athletes could potentially hit that speed threshold during games. But is the total of reps needed for speed maintenance—probably around two to four—achieved during a normal game? And do all players on the field reach that? What about the bench players? If games aren’t a great source of speed stimuli, especially for all the players, it can also be a challenge when a majority of in-season training/practices are focused on refining sport-specific skills and simply just bouncing back (recovering) for game day.

But there’s good news: speed work in-season is relatively easy to get done with a sound understanding of speed training principles and a little bit of creativity. The question becomes: how do we train efficiently and effectively to at least maintain our speed gains while prioritizing practices and games and also keeping athlete-readiness as high as possible? First, we must understand both the foundations of in-season training and the main principles of speed training itself; then, we can dive into the different types of speed to work on and how to creatively do it in-season.

Video 1. A compilation of some of the exercises performed on game day based on the speed training theme of the day.

Core Principles

In-season training can be summarized in a simple, three-word phrase: stimulate, not annihilate. “The hay is in the barn” is a cliche that summarizes this pretty well; for the previous months of the off-season and pre-season, the athletes have been grinding, breaking down their bodies, and building a good foundation to now show everything off in competition. How do we “stimulate” those skills and adaptations from all the prior training to keep them sharp and maintain them, as opposed to “annihilating” them like we did in the off-season? The answer is chasing intensity (speed), not volume (number of reps).

In-season training can be summarized in a simple, three-word phrase: stimulate, not annihilate, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XAnd next, if we know what counts as stimulation for an athlete’s speed, then we can effectively stimulate it. As mentioned earlier, Charlie Francis’ 95% threshold still applies (this isn’t the only topic I write about, I swear…). This simply means that an athlete must sprint at 95% or faster of their top speed to count as a “high intensity” rep that stimulates their speed. For example, if an athlete’s best speed during a Flying 10 Yard sprint (training top speed) is 20mph, they must sprint 19mph or faster to stimulate it.

Additionally, the principles of being well rested enough (one minute rest of every 10 yards sprinted hard) and everything else that goes into good speed training still applies.

Types of Speed and Application

We know that we have to sprint as fast as possible and do so at least once a week. But what specifically do we apply that to? Is it good enough just to sprint and walk back? Unfortunately, no. I break my in-season speed training into four main buckets:

- Short acceleration

- Long acceleration

- Top speed

- Change of direction/agility/deceleration

I know that might seem like a lot, but with examples it’ll make a lot more sense.

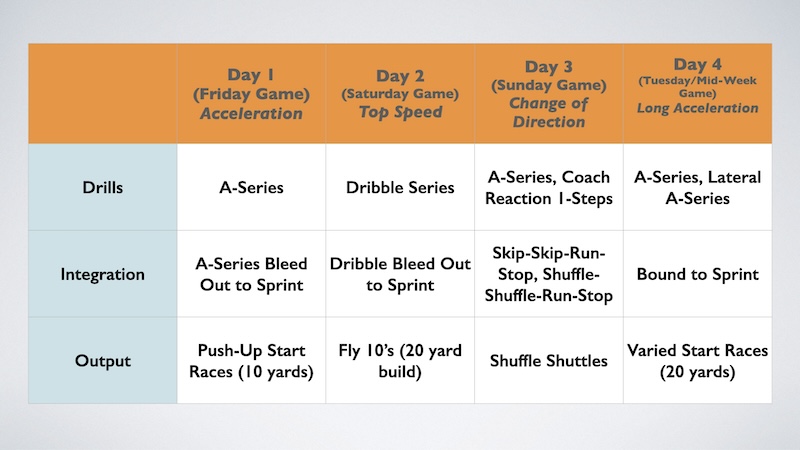

In trying to be as efficient and effective as possible, I was able to stimulate all these types of speed, getting two-four reps a day across four different 15-minute warm-ups in-season, including on game days. The general outline per day was as follows:

- Six minutes of general preparation, dynamic stretching, etc.

- Three minutes of “personal stretch,” so the athletes had a chance to specifically warm-up whatever they needed that day.

- Six minutes of speed drills (both for mechanics and for output), depending on the speed-theme of the day.

In-Season Example

In theory, this all makes sense (at least I hope it does). But what does it look like in real life? Let’s take you through what I did in-season with a Power 5 college baseball team.

Time is always going to be a prized resource in the sports world, but especially in-season. So, what’s a chunk of time you’ll always get with your athletes, no matter what? The warm-up. The warm-up is a simple, consistent piece of training you can use to microdose your speed training in-season.

The warm-up is a simple, consistent piece of training you can use to microdose your speed training in-season, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XBelow is an example of the four-day warm-up template I used with my baseball athletes:

All Four Days: Begin with General Dynamic Warm-Up

The first nine minutes of my warm-up remain largely the same. I think with such a varied back-half of the warm-up, it’s valuable to give the athletes some consistency for their bodies and their minds on game-day.

- General dynamic stretching: jogging, backpedaling, walking quad stretch, alternating side lunges, walking lunges, shuffling with big arms, etc. Ending with some sort of low intensity plyometric-like ankle jumps. Just general things to raise the body temperature and heart rate and address some of the big muscles/movement patterns.

- Three-minute personal stretch: this is exactly what it sounds like and this is how I describe it—”You have three minutes to do what you have to do, drills/exercises/muscles that we haven’t addressed yet that you like, to get your mind and body right for the rest of the warm-up.” Some athletes do static stretching, some do more dynamic stretching, some do specific “prehab” exercises the athletic trainer or a coach back home gave them. This is also a great opportunity as a coach to check-in with the athletes.

Once those three minutes are up, we move on to the fun stuff.

Day 1: Friday Game: Acceleration

- Drills: A-series

- Examples: A-Skipping, Double A-Switches, Triple A-Switches, 3-Hop A-Switches, Building A-Run, etc.

- Integration: Blending the drills to all out sprints

- Examples: A-Run to Sprint, Skip-Skip-Sprint

- Output: Push-Up Start Races, 10 yards, two-three reps

Video 2. A few of the drills referenced for Day 1, short acceleration focus, including Building A-Run to Sprint and a few Push-Up Start variations.

Day 2: Saturday Game: Top Speed

- Drills: Dribbles Series

- Example: Ankle Dribbles, Shin dribbles, Knee dribbles

- Integration: Dribble Bleed Out to Sprint

- Output: Build-Up Fly 10’s

- Example: three reps at 90% effort, 95% effort, and “+95%” effort of the player’s choice (basically 95-100%, whatever they’re feeling)

Video 3. A few of the drills referenced for Day 2, top speed focus, including Ankle-Shin-Knee Dribble to Sprint (at least however fast I could get into in 10 yards for something that’s usually +20 yards).

Day 3: Sunday Game: Change of Direction

- Drills: A-series, coach reaction 1-steps

- Examples: Lateral 1-Steps, Shuffle and Return, Crossover and Return

- Integration: Skip-Skip-Run-Stop, Shuffle-Shuffle-Run-Stop

- This also works as a great deceleration stimulus for the week

- Output: Shuffle Shuttles, two-three reps

- Example: Crossover-shuffle out, crossover-shuffle back, run and stop 10 yards away

Video 4. A few of the drills referenced for Day 3, change of direction focus, including Change of Direction 1-Steps (Lateral and Crossover), deceleration drills (Skip-Skip and Shuffle-Shuffle-Run-Stop), and an example of a Shuffle Shuttle.

Day 4: Tuesday/Mid-Week Game: Long Acceleration

- Drills: A-Series, Lateral A-Series

- Integration: Bounding, Bound to Sprint

- Output: 20 yard races (vary starts), two reps

Video 5. A few of the drills referenced for Day 4, long acceleration focus, including the Lateral A-Series (Lateral A-Skip) and Bound to Sprint.

Bonus: Deceleration

Deceleration doesn’t need its own dedicated day, in my opinion. It’s the most soreness-inducing because of how fast the legs are eccentrically working to slow the athlete down. But on the flip side, it’s great to really draw out some intensity from the athletes’ muscles. I try to throw in two deceleration stimuli about twice a week. This can be in a “run-stop” drill like during the integration, or you can make a 10- or 20-yard race end with “stop on the line.”

There are plenty of really smart people, like Damien Harper, who can explain the value of deceleration. Just remember that if we’re going to hit high speeds, we need good brakes—and fast deceleration is a very high and unique amount of force put on the athletes. Short and sweet, don’t forget a few simple deceleration reps per week.

Considerations

There’s one big consideration that’s worth mentioning… How do I know my athletes are hitting +95% of their best speed? It’s simple: I don’t. Without sprinting through timing lasers to objectively know if my athletes are or are not running fast enough, it’s merely a guess. The main premise of this article is assuming the athletes are going as fast as they can when it comes time for the last two-four reps at the end of warm-up. However, I still believe this is a really good option with all things considered.

There’s one big consideration that’s worth mentioning… How do I know my athletes are hitting +95% of their best speed? It’s simple: I don’t, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XAll training is a trade-off. You must combine all the different variables of that day and make an efficient and effective game plan: time of year, time allotted to training, training goals, and other training the athlete has that day. Within all the factors on game day, only having 15 minutes, having to warm up the entire team, maybe being in a different city/state, and so on.

Here are a few things I can control to try to help my athletes sprint as fast as possible:

- My communication of intent. By explaining a little bit of the “why,” athletes understand their responsibilities and expectations to give their all in those last few reps.

- Rest times. Making my athletes walk back after a sprint, or a slow jog then I’ll give them 30 seconds of rest, I know their bodies are at least fresh enough to potentially sprint as fast as possible.

- Experience of the warm-up. Being intentional with the art of coaching and making the last few reps as engaging as possible. This is very simple: make it a race and call out the one or two winners. Works every time.

You might be concerned about athletes doing too much on game-day, as the game is obviously the priority. I totally understand and there’s an easy way around this. Let’s say you have four reps of 10-yard races for the end of the warm-up, you can say something like this “Starters (starting in the game that day), hop in the for first two reps, then just watch and be encouraging for the last two. Everyone else, four good races to finish, don’t lose.” The starters get their high-quality speed stimuli and the non-starters take advantage of the opportunity to get a good speed workout in.

Last, what about warming the athletes up for the other days of the week, like for practice? In this example, Monday, Wednesday, and Thursday? Those days for me were only 10 minutes for the warm-up, so there are a few reasons why I kept those simple and didn’t toss in any speed-specific themes. First, the amount of time, obviously. Second, the game days would be considered “high-intensity” not only with the speed-specific warm-ups, but also the game itself. The athletes need “low-intensity” days to follow a traditional high-low training model. A high-low training model basically means alternating high- and low-intensity training days to allow for mini, built-in recovery days within a training week. Yes, I only control 10 minutes of the entire day on non-game-days, but I control what I can control.

Getting Results

Hopefully you now understand more about the foundations of speed training, what goes into an effective speed training session (even if it’s just a “warm-up”), and how you can be creative within the constraints of a given training session to maximize your time with your athletes.

This routine was very easy to execute and produced numerous insights in watching it play out through the course of a long and grueling 14-week season with 52 games. Although I didn’t have the opportunity to get my athletes in timing lasers during this time, we had no lower-body soft tissue injuries and received positive feedback from athletes. There was enough autonomy in effort that the starters could self-modify to give themselves what they needed, there were enough opportunities for the non-starters to feel like they still got really good work in and continue making progress despite not playing, and there was enough consistency that the athletes knew what to expect on each game-day so they were mentally prepared for it.

With these real-life examples, you should have plenty of ideas as to how you can apply this in your own setting. You and your athletes grind all off-season—maintaining (and maybe making more) gains in-season can be as simple as 10-15 minutes a day and some thoughtfulness behind your programming.

References

1. Issurin VB (2008) Block periodization versus traditional training theory: a review. J Sport Med Phys Fit. 8:65–75

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF