One of the great challenges faced by high school strength and conditioning coaches is developing an effective protocol to develop student-athletes in our performance programs. Having an effective entrance plan with well-thought-out progressions goes a long way to efficiently move your athletes along the path to high performance within your programming.

I’m writing this article to offer insight into how we begin to develop our athletes to prepare for the climb from our Block Zero (Block 0) program to our Block 4-Elite level.

Background

When I first began working with athletes over 20 years ago, I had very little experience differentiating programming based on training age. I came into the field from the sport coach side. My experience was using the back squat, deadlift, bench press, and hang clean. I’m embarrassed to say that at that point, I basically used the same program for all my athletes.

A few years into my coaching career, I began to see that there was another, much safer and more effective way to program. Since then, I’ve continued to chase knowledge and pursue best practices for working with athletes with a young training age. It wasn’t until about ten years ago when I was tasked to work with 3rd– to 8th-grade athletes that I really began to fine-tune what we now do.

While the base of our program is set, I continue to tweak and seek ways to become more efficient in our progression and regression protocols. I have learned from so many great coaches, and it would be impossible to list all who have contributed. I hope you can use this article the way I have used so much of what I’ve learned over the years on this topic. I hope that you can take something you see here and find a way to use it to your advantage.

About the Block Zero Program

Much like everyone else, our Block 0 program at York Comprehensive High School (YCHS) is a basic movement program. We teach our athletes mobility, body awareness, jumping and landing mechanics, stability, and all the basic movement patterns they’ll use during their time in our program. Of course, Block Zero was a term that was developed by Coach Joe Kenn to describe his introductory program. It’s become a general term many use to label their intro program. Although you’ll find many different plans depending on the coach, most contain the same basic ideas and principles outlined in Coach Kenn’s plan.

At various times I’ve had more direct control over the Block 0 program than others. In my last position, I ran a sports performance camp year-round that was attended by most of our young football players. I also did a summer camp in our weight room, teaching the basics of the program. In my current position, I don’t have access to our athletes until the Spring of their 8th-grade year. However, we have strength and conditioning classes at our middle school, and we’ve coached the teachers on our program. Each year, our rising freshman get a little better at what we do. I urge you to be as involved as possible with the young athletes in your program. If you’re not doing this yet, you’ll see an immediate impact when you start.

Basic Movement Overview

Our Block 0 program has many small variations and progressions. The chart below shows a very basic outline of what we do at the very beginning of the program. This is a multi-year plan, so you only see the first steps.

During Block 0, the athletes will learn a general mastery of the following:

- rocking

- neck nods

- cross crawling

- crawling

- general movement skills

- deceleration

- basic sprinting techniques

- straight leg bounding

- bodyweight movements

- breathing

- mobility

- tumbling

- eccentric and isometric bodyweight

- basic jumps with landing focus

- medicine ball throws

- weighted pushing and carries

| Bilateral Squat | Hinge | Horizontal Push | Vertical Push | Unilateral Squat | Pull | Pushes and Carries |

| Eccentric Air Squats (3-3-x tempo) | “3 Jump” Power position | Push-up plank and shoulder touch | PVC Shoulder press | Eccentric Split Squat (Hands overhead) (3-3-x) |

High to low inverted rows (feet to floor up to elevated) | Sled Push-loaded |

| Plate Goblet Squat | Partner Push/PVC Hinge | Push-up plank leg lifts and hand walks | Med Ball Shoulder Press | Short Box Rear Foot elevated split squat | Chin Up hangs to assisted chin up | Farmer Carry with DB |

| Goblet Squat | Wall Drill | Eccentric hand release push-ups (3-3-x tempo) | Kneeling Med Ball Press (Stay Tall) |

Short Box Front foot elevated split squat | Assisted chin up to eccentric drop (slow as possible) | Waiter Carry with KB |

Our goal is to have each athlete come to us with a basic mastery of each of the above movements and progressions. They’re also exposed to more slightly advanced movements as they get close to the Spring of their 8th-grade year. Of course, that won’t happen 100% of the time, and it never will. We just hope to have as many as possible as high performing as they can be when they come to us.

8th Grade Spring Semester: The Key Transition Period

As high school coaches, ideally we’ll be able to either participate directly or at the very least program for our athletes from as early an age as possible. At YCHS, I’m particularly blessed because our middle school has weightlifting classes for both male football players and a separate female class. Our football program also has weightlifting sessions in the summer at the middle school as part of the team’s summer practice schedule. It’s a great opportunity for our athletes to take part if they choose to do so.

Our administration also has allowed to me spend time during the school day to provide professional development for the staff and coaches as well as coaching the athletes at our middle school. During the professional development sessions, I lay out a general plan for the areas I’d like to see developed. This includes all areas of our Block 0 program, including sprinting and jumping/landing techniques. I hope that our middle school athletes can master the most basic techniques and have exposure to some next level movements.

At the very least, I hope our athletes will have a working knowledge of hinge and squat patterns. Of course, there will always be athletes who don’t end up in a class and come to us with a zero training age. It’s not uncommon to have freshmen and sophomores come in with the same issue. For these athletes, we go straight to the very beginning, though we obviously don’t have the time to spend multiple years mastering Block 0. Instead, they’ll move at a pace that will allow them to master the most basic techniques in the weight room. These older Block 0 athletes will still have to pass all our entrance standards to the various levels of weightlifting movements, jumping, and landing. Unfortunately, they lose some of the movement skills practice that comes with the multi-year Block 0 program.

Starting in the Spring semester of their 8th-grade year, they begin to participate in our after-school sessions. Most of these athletes are female because both 7th and 8th-grade football has a weightlifting class during school hours. Our middle school and high school athletes are together during this time, which can get pretty chaotic for me. I’ll have male and female Block 0 to Bock 4 athletes on a multitude of calendars based on sports season participation.

It’s important for the coach who has the most experience to work with the least experienced athletes, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XIf you plan to run your sessions this way, it’s imperative to have help. I usually have two to four sport coaches working with me during this time. While it’s tempting to work with our more advanced athletes and have the sport coaches focus on the younger group, we do the exact opposite at YCHS. I spend the vast majority of my after-school program with my 0 and level 1 athletes. The sport coaches will be with our 2-4 groups. If I teach our young athletes exactly how we want to do things, I believe they’ll experience success at our higher levels with less attention. It’s important for the coach who has the most experience to be with the least experienced athletes. The only exception to this rule is the week we test.

Jump and Land Athletically

When the 8thgrade Block 0 group first comes to us, we want to get a general idea of where each athlete stands concerning what we hope they have mastered. I also want to understand each person’s overall level of athletic ability. We do this by watching them (with very little coaching cue) hop over five short agility hurdles. I tell them to jump and land, hold the landing for two seconds, and repeat.

We chose this test because it’s a great indicator of how much time they spent in our Block 0 program. Having an athlete jump and land also gives us a rough estimate of their athletic ability. Athletes who have a good level of experience will show a level of technique that a less experienced athlete won’t—particularly how they initiate and land.

We coach the “smash the egg” technique. I cue them that they have an egg on the back of their hamstring and when they jump, they need to “smash” the egg with their calves. We also approach landing with a very detail-oriented style: soft landings initially (with more stiff and explosive techniques coming later in the process) with toe to heel progression, feet shoulder width and forward, proper lower body flexion, and upper body bent forward close to 45 degrees. They hold for two seconds and repeat the effort over each mini hurdle.

This process is especially important for our female population. Knee injury is so prominent among female athletes that we, as strength coaches, have to help them not only strengthen but learn to move efficiently. And this is part of that process. I understand the argument that athletes in sport don’t often have the opportunity to land perfectly. But I also firmly believe that teaching the correct way to absorb force and stabilize while adding strength will help an athlete make the needed corrections in less than perfect landing situations.

Teaching how to absorb force & stabilize while adding strength helps self-correction in less than perfect landing situations, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XFollowing this initial observation time, we go into a coaching period. We’ll review the correct techniques and explain our cues. Then we go through the drill a few more times, this time correcting and teaching the athlete to self-correct.

Constructing Power Position and Hinge Mechanics

The next step in our evaluation is hinge progression. We begin by reviewing the power position. I can’t recall where I heard this cue, but it’s my favorite: “You’re talking to a friend in class, and you sit on the edge of a desk to talk.” Next cue is superman or superwomen position, not by the sticking chest out or by pushing shoulders back but by “squeezing your big back muscles” up and squeezing hands together into a fist in front of you. This locks the athlete into a nice tight power position with their core and back. I have them hold and release this position to get a feel. I then have them hop three times and land without adjusting their feet but by getting that feel back. I’ve found that hopping and landing without thinking about foot placement often result in the athlete finding a natural power position.

Hopping and landing without thinking about foot placement helps athletes find a natural power position, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XStep two is to partner up the athletes and have them stand back to back. We cue “power position” and then “push back with just your butt,” and they push against each other and reset, this time taking a step away. We repeat this process until they are far enough away from each other to complete a hinge movement. One cue that’s very helpful when teaching this concept (especially with basketball players) is having them imagine themselves with their back to a basket, ball in hand. Tell them the defender is playing tight and they need to create space to make their move without fouling. Often, they instinctively sink their hips and push the butt back into a really nice position.

Once we have that established, we’ll get out the PVC pipes. The athletes will get in the power position with the PVC pipe behind them running from overhead toward the floor aligned with the spine and glutes. The athlete’s top hand will be on the top of the PVC pipe with the elbow held at a 45-degree angle. The bottom hand will be behind their back, holding the PVC pipe in and against them. The athletes hinge in this position, making sure the PVC pipe stays connected with the upper back and top of their glutes as they bend. This movement teaches the movement pattern we’re looking for very efficiently.

The last step on the first day is the wall hinge drill, which is very similar to the partner drill. We also use the wall hinge drill as a regression movement for athletes, even at a higher training age. The athlete stands at the wall a few inches away in power position and pushes their butt back to touch the wall. They then step out and repeat. They’ll hold the position each time until I cue corrections. The number one thing I correct is the athlete lifting their toes and rocking back on their heels to get their glutes to the wall.

Introducing Barbell and Bodyweight Squatting Patterns

Once we’ve taught and reviewed the hinge, we move to the squat. Each of these teaching progressions could be an article in itself, so I’ll try to give the most streamlined version possible.

Step one is the eccentric air squat with a 3-second eccentric and isometric (pause) phase and a quick concentric phase. We cue the athlete to get into the power position with hands in front, take a breath through the nose (mouth closed) to expand stomach, squeeze the back (as taught earlier) and hands, push the hips back slightly, and slowly sit back on their heels. When they hit the bottom of the squat, they hold for 3 seconds then breathe out as they pop out of the squat as quickly as possible in a controlled manner.

We’re looking for weight pressing on the heels, superhero chest, body upright with a neutral chin, and knees externally rotated tracking over the outside toe. One common mistake I see is the athlete trying to initiate movement with knees instead of hips. That gets them up on their toes and makes it hard to sit back on the heels. From this, we can tell a great deal about the athlete’s mobility.

Next, we’ll add a plate and eventually a kettlebell or dumbbell to the same movement, which gives us even more information on possible dysfunction. We evaluate from the ground up checking for ankle mobility issues, possible knee valgus, hamstring strength and mobility, and core and thoracic strength.

Our final initial step with our lower body evaluation and preparation phase is our unilateral squat progression. We don’t often get to this on day one. If we do, we start with a split squat (even though it’s not a true unilateral movement) version of the eccentric air squat and progress in the same way. Much of the process is the same.

My main cues involve the front knee since athletes often push their hips forward instead of down toward the floor. This causes the knee to shoot out past the front of the foot, throwing the shin angle into excessive flexion. Also, if the knee is out past the toe but the hips are moving down, they likely have their feet too close together in their split. There are many other things we need to look for and coach with split squats, but that’s another article.

The second day our athletes come to us, we shift to the upper body portion of our protocols. These include horizontal push, vertical push, pulls, and weighted pushes and carries. I’ll cover these in depth in a future article because upper body training—while important—has some complicated politics and philosophies that merit a full breakdown.

Stay Patient and Never Stop Teaching

I hope that this article has given you insight into how we start the athletic development process for sports performance at YCHS. We pride ourselves in physically preparing our student-athletes with an evidence-based, step-by-step process that will lead them to advanced barbell movements with heavy loads. As coaches, sometimes we’re in a hurry to have our athletes lifting heavy and doing these advanced movements. I urge you to avoid this path and instead “slow cook” your athletes.

The better prepared athletes are from a young training age, the more strength and power they'll produce in the upper levels of your program. Share on XWhether it’s using a program like the one I’ve outlined here or another one based on similar concepts, I hope you find the program that’s right for you and your athletes. In the long run, the better prepared they are from a young training age, the more strength and power they’ll be able to eventually put out when they reach the upper levels of your program. As always, feel free to reach out to me to discuss this or any topic. If I don’t have the “why,” I can point you in the direction of someone who does.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Contextual Sprinting and Developing Game Speed with Paul Caldbeck

Paul Caldbeck, MSC, ASCC, CSCS, is currently a consultant performance coach, and doctoral candidate at Liverpool John Moores University, where his research centers on contextual sprinting in soccer. He previously held the position of Physical Preparation Lead at a Premier League soccer club. Caldbeck has extensive experience in strength and conditioning and sport science across a range of sports.

Freelap USA: Contextual sprinting is important for coaches in sports such as soccer, lacrosse, American football, and rugby. Can you explain how to get started analyzing a sport beyond passing the eyeball test? How does one break down the small events during a game to summarize the patterns of the sport better?

Paul Caldbeck: Sprinting occurs during the most crucial moments of field-based team sports. This is typically as a result of an offensive player seeking separation from a defensive counterpart and vice versa, a defensive player attempting to maintain distance. These efforts often determine the eventual outcome of the match, and, ultimately, effectiveness in these key moments is how a player will be judged.

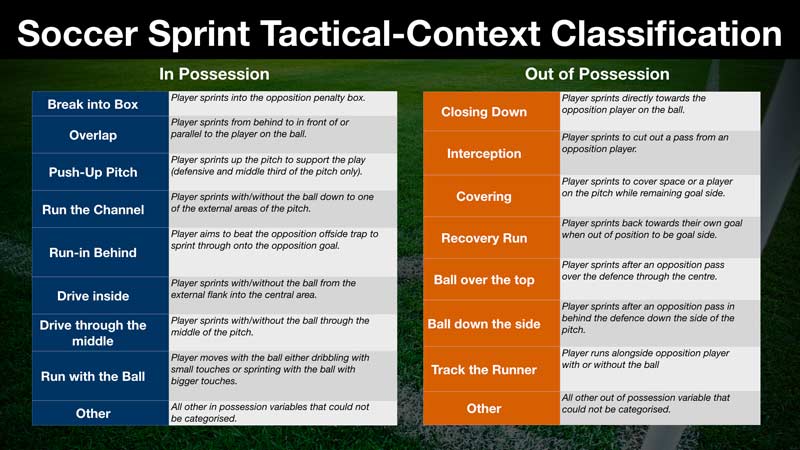

While these sports are obviously chaotic in nature, we can attempt to reduce match activities into key, defining contexts. Such a classification system has been previously developed in soccer (Table 1)1 and can easily be completed in similar sports through a systematic process of categorizing phases of play and specific actions during a match.

For my own doctoral research into contextual sprinting in soccer, I developed two systems. The first sought to quantify “how” sprinting in soccer was completed, focusing on the types of movement that made these efforts “soccer-specific.” Typically, as performance practitioners, we assume sprinting during a match is different than during track and field, but little data existed to back this up. Thus, the first stage of my thesis aimed to establish whether these differences actually existed and how pronounced they were. By better understanding the movements associated with the key moments (sprinting) during a soccer match, we can look to direct our programming toward what matters most.

However, it is obviously the case that any movement that presents itself during a match is a direct result of the match itself, and the athletes’ perception of the match. Therefore, the second system we developed—the Soccer Sprint Tactical-Context Classification System—aimed to quantify “why” sprinting occurred during soccer, and we created it from previous work in the area. We can then implement this type of system and produce profiles for specific positions, allowing us to develop our performance programs specifically relating to these key moments of a match.

Unfortunately, there is currently no automated means of attaining this data, to my knowledge, so it is a case of old school video analysis! Getting a reasonable sample size for one athlete can take a couple of hours. But once we have this data, it is absolute gold dust for performance coaches. In Premier League soccer, a player may sprint around 20-40 times during a match. If we can even slightly enhance their effectiveness in one of these efforts, then we can potentially have a direct influence on match outcome.

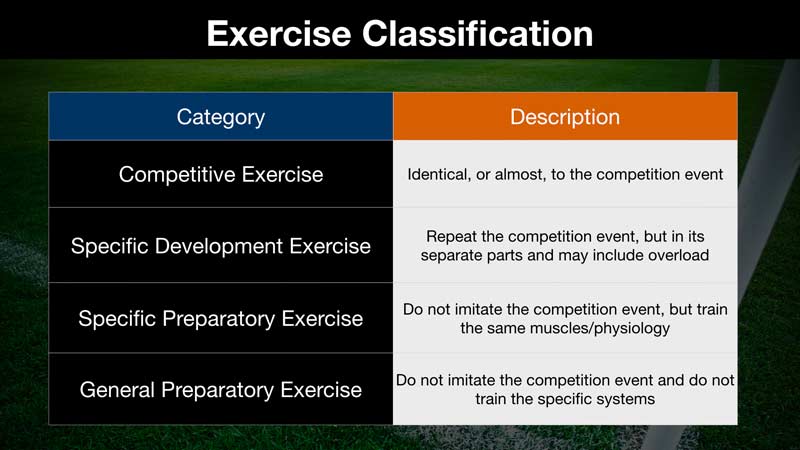

Using this context information, and by thinking of all physical training on a spectrum from specific to general, we can begin to design a holistic program to directly influence on-field performance by “reverse engineering” these contexts. I am a big fan of work by the likes of Shawn Myszka, where we facilitate the learning of the athlete through exposure to specific contexts and “repetition without repetition.”2

So, our first stage would be to expose the athlete to these sprinting contexts in practice. If, for example, a soccer center back repeatedly sprints due to a ball down the side of the defense, then we start by designing drills that replicate this scenario and manipulate the constraints (organismic, task, or environment). These may be different positions in the defensive line, different numbers of offensive players, or a different pitch location, for example. This allows the athlete to truly develop the coupling between perception and action through means such as enhanced pattern recognition.

The next stage in the process would be to begin to isolate the specific skills involved in these contexts. So, in the above example of a center back facing a ball down the side, they will likely complete a lot of sprints from a rear initiation position, which involves a drop step movement. Again, we can create drills to isolate this action; we can easily incorporate them into warm-ups.

This allows us to begin to overload the specific force demands of the actions by completing them with maximal effort and focusing on technical efficiency. The learning is again achieved through the athletes’ exploration of the constraints the drills place upon them, rather than rote learning of footwork drills. Certain drills may involve specific match-related stimuli, and at other times we sacrifice this for more specific training.

Beyond this stage of the spectrum, we begin to forego specificity for the ability to overload the physiology stressed in the activity. So, in this sprinting context, we may seek to develop power production and the ability to apply it in multiple directions. For example, we may first employ resisted sprinting and multidirectional power exercises. At a certain stage, we will favor overload completely over specificity and look at standard weightlifting or squat jumping—general power production methods. And finally, we have our most general physical development methods, such as strength training and any prehabilitation work the athlete may require.

We may employ each of these methods concurrently or as the focus of certain mesocycles. However, the broader point is that we always relate our performance enhancement program back toward the key contexts that can ultimately determine whether the team wins or loses, or the athlete is successful or unsuccessful.

I believe the key development for the future of performance training is better integration with match-related activities, says @caldbeck89. Share on XWhile I am a firm believer in the importance of general strength and power training, I believe the key development for the future of performance training is better integration with match-related activities. We shouldn’t be afraid to discuss sport-based movement with head coaches. I believe we sell ourselves short as an industry if we just concern ourselves with weight room numbers, and the likes of Shawn Myszka are really taking us to another level.

Freelap USA: What is a good way to assess curved sprinting? Many coaches time the speed of running in a circle, but should we look at right and left information or compare it to linear speed? Where are we going here with testing curved speed?

Paul Caldbeck: Depending on the method of measurement used and how we define curved sprinting, the majority of sprint efforts in field-based team sports will involve some degree of curvature. My own doctoral research observed 87% in soccer, across all positions. Here though, the problem lies with how we as performance scientists decide to reduce these efforts into defined categories such as curves and swerves, creating potential contradictions within the research. However, regardless of methodology employed, our athletes need to be effective at maintaining velocity, or accelerating, while traveling in a curvilinear motion, and at varying degrees.

Regardless of methodology employed, our athletes need to be effective at maintaining velocity, or accelerating, while traveling in a curvilinear motion, and at varying degrees. Share on XThe literature directly for team sports is scarce, but from research on track sprinters, we know there are biomechanical differences between curvilinear sprints and typical linear efforts. There are differences in force demands, such as the inside leg generating greater inward impulses and turning, and the outer leg producing greater anteroposterior demands compared to straight line sprinting. Obviously, these studies are completed on the standardized curve of an athletics track, whereas in team sports, these curves will frequently vary in distance and degree. But what is clear is that curved sprinting is a unique skill and if sprinting can determine match outcome, and most sprints will involve an amount of curvature, then this should be a key focus of any good performance program.

With regard to testing, the philosophical purpose of a testing battery is key to the selection of a test for curved sprinting. Are we attempting to truly test an athlete’s ability to sprint during a match, or relying on a general test of curved sprinting ability that may reflect an athlete’s potential ability during a match? Here many “combine style” testing batteries fall foul of Goodhart’s Law where, “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Research using the NFL Combine results has shown this method of testing is only a “modest” predictor of future performance. But, while being cognizant of these inherent flaws, we can still analyze an athlete’s broad capacity to run fast along a curve.

Recently, attempts have been made to ascertain average angles of sprinting in soccer using the tangent-chord method.3Here, the study concluded an average angle of 5 degrees but potentially as large as 30 degrees. So, a standardized testing procedure may involve the comparison of distance-matched (say 30 meters) linear, and 5-degree left and right curved sprints. A decrement value can then be ascertained for time to complete or maximum velocity attained, both for linear versus curved and left versus right.

For example, if an athlete can attain 10 ms-1in a 30-meter linear sprint, but only 9 ms-1 during a 5-degree, 30-meter sprint, we would get a curve decrement of 10%. This would then give us a general, broad understanding of an athlete’s curved sprinting ability. However, it is crucial to understand the limitations of such a method, such as the potential skill differences across a range of varying angles and how far removed this type of effort truly is from sprinting during a match.

While this method satisfies our scientific desire for test validity and reliability, nothing can match consistent observation of an athlete during competition. For me, that has to be our foundational assessment method. Controlled testing procedures should only ever support this, rather than be the principal driver of our programming.

Freelap USA: Many coaches argue that pure peak velocity needs to be used to sustain global output and raise the CNS ability, while some coaches only care about practicing. How do you get an athlete better while ensuring that actual transfer is occurring?

Paul Caldbeck: Naturally, the answer to most polarizing debates lies somewhere in the middle, and I certainly believe this when it comes to general versus specific methods. While I think it is important to be specific with a lot of our training, at times it is necessary to sacrifice this specificity for the opportunity to overload certain underlying capacities that are crucial for performance. For me, this is the case with sprinting as much as it is for general barbell strength training.

At times it is necessary to sacrifice specificity for the opportunity to overload certain underlying capacities that are crucial for performance, says @caldbeck89. Share on XMany contextual sprinting efforts completed in sport are inherently submaximal—Ian Jeffreys refers to these activities as “game speed”4—whereas maximum velocity capability for team sport athletes is a “capacity” quality. Obviously, an increased capacity gives an athlete the ability to achieve greater performance in these submaximal efforts: A 9 ms-1athlete is unlikely to be more effective at game speed movements than one who can achieve 10 ms-1. It is therefore crucial to still consider enhancements of maximum velocity, though the real question is, how much is enough!? At the elite level in team sports, maximum velocity likely becomes less of a determinant of performance and the ability to “exploit” this capacity during a match becomes the key.

However, sprinting at maximum velocity in a controlled practice environment should be a fundamental aspect of any team sport athlete’s physical development program. Not only does it “vaccinate” against potential hamstring injury, but the kinetic demands of maximal sprinting are also unparalleled. It is almost impossible to match this force application demand in such short time frames elsewhere in our programming.

Similarly, athletes should well understand the standard “rules” of good sprinting before they learn to break them during more sport-specific activities. Sprint coach Jonas Dodoo often references projection, reactivity, and switching as being fundamental to running fast; this is as true for team sport athletes as it is for track sprinters.

The issues arise, though, when the sole focus of our programming becomes improving an athlete’s 40 time. While, as noted, linear speed will always be important, we should not seek constant improvement at the expense of sport-specific sprinting skills. If an athlete is unable to effectively “spot the gap” faster than an opponent and utilize efficient movement skills to apply their velocity capacity, a 10th of a second faster 40 time is useless. A performance coach’s role is to decipher an individual’s performance limiter.

As an aside, the sport I have been involved with most is soccer, and I believe that coaches’ current focus on small-sided games in practice is likely a huge factor in the prevalence of hamstring injuries. From a very young age, athletes are constantly exposed to these reduced area drills, which work great at increasing technical exposure, but are likely developing ineffective movement skills when then placed into a match situation in a much larger area. Learning to run at high velocity over 30+ meters should be a fundamental aspect of a developing soccer player’s program. I can’t recommend highly enough the benefits of learning to sprint effectively at the local track club.

Freelap USA: Athletes who test well in all areas of performance still have to be skilled. How do you work with team coaches to determine where real deficits are? When does it become the responsibility of the sports coach and when does a fitness or performance coach need to step in?

Paul Caldbeck: Ultimately, the performance staff is there to support the sport coaches, and the direction and philosophy of the team is always their responsibility. With respect to performance, the determination of any deficit should consequently be a collaboration between sport coaches and performance staff. It’s crucial to understand that no sporting skill is performed during a match without an element of physical demand, and vice versa. Thus, an optimal program will always seek to fundamentally combine the two.

A direct line of communication between sport coaches and performance staff is fundamental to an organization’s success. While a head coach should have the ultimate say on the direction of an athlete’s programming, we as performance staff should, with our expertise, be a strong voice in these discussions. It is our responsibility to prove our worth to the coach.

After performance staff establishes key physical contexts through a classification system, these contexts allow us to talk in the coach’s own game-referenced languages, says @caldbeck89. Share on XAs discussed above, we can establish a quantification of the key physical contexts through a classification system. We can even weight these contexts for importance to match outcome and assess an athlete on their performance in these key moments, thus developing a needs analysis of potential performance deficits. Rather than discussing an athlete’s irrelevant 40 time or power clean 1RM, these contexts allow us to talk in the coach’s own game-referenced language. This can then increase buy-in from coaches and athletes and create a common language across the organization.

Freelap USA: How do we make practice better? A lot of strength and conditioning coaches get frustrated with team coaches, as they are usually left with very little time and energy to train outside of playing and practicing. What do you suggest for merging on-the-field work without resorting to a cliché warm-up of mini hurdles and cones? How do we get speed injected into training?

Paul Caldbeck: As discussed, the ultimate responsibility lies with the head coach, and performance staff is in place to support them. I don’t believe it is healthy to view our practice as competing for time with sport coaches, though I do understand this frustration. I believe a paradigm shift to reverse engineering from these key contexts to rationalize our interventions to coaches is the key to “selling” our demand for time. Rather than viewing training in silos as weight room time and sport time, all types of practice should be seen as training, and this shift is key to getting coaches on side. I feel this is often better achieved in track and field than team sports.

Rather than viewing training in silos as weight room time and sport time, see all types of practice as training. This shift is key to getting coaches on side, says @caldbeck89. Share on XWith the knowledge of the ultimate physically demanding context we seek to enhance, all facets of training can be skewed toward focusing on this. The messages from performance staff should always relate back to this context: it is the reason we lift, the reason we complete linear sprints during a warm-up, and the reason we do our post-practice yoga. With this in mind, performance staff should seek to influence aspects of daily practice; this is common in soccer.

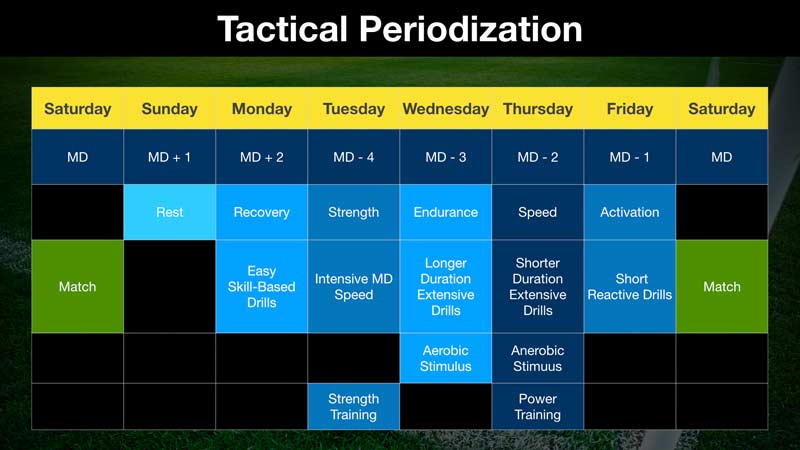

The head coach will typically discuss the theme for the day’s practice with the performance staff to ensure optimal physical development. They will hope to achieve the physical goals for the day/week within the broader macrocycle as much as possible within the regular practice.

For example, this “tactical periodization” approach may dictate that the day’s training theme is “intensive/multidirectional speed.” Practice drills will be selected to encourage regular intense changes of direction; this is typically achieved by reducing the space available in drills. Alongside this, weight room time may consist of high force activities, warm-ups may involve closed change of direction drills that reflect the key sprinting contexts, and the performance coach’s drill time may specifically mimic these intensive sprinting match contexts.

Training the specific key contexts should thus be incorporated into typical practice rather than competing for time. For example, in soccer, a coach may employ a “crossing and finishing” drill with the aim of practicing a player’s specific sport skills in these actions. They can easily manipulate to provide a movement skill acquisition and physical stimulus; thus, optimally combining perception and action. These drills then provide “repetition without repetition” and facilitate the athletes learning to apply their physical ability in a specific context through exploration.

As noted, game speed is about much more than pure physical capacity. By constraining the drill in different manners, we can alter the types of sprint efforts completed by the attacking player to suit their physical needs.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Ade, J., Fitzpatrick, J., and Bradley, P.S. “High-intensity efforts in elite soccer matches and associated movement patterns, technical skills and tactical actions. Information for position-specific training drills.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2016; 34 (24): 2205-2214.

2. Myszka, S. “Movement Skill Acquisition for American Football Using ‘Repetition Without Repetition’ to Enhance Movement Skill.” NSCA Coach. 2018; 5(4): 76-81.

3.Fitzpatrick, J.F., Linsley, A. and Musham, C. “Running the curve: A preliminary investigation into curved sprinting during football match-play.” Sport Performance and Science Reports. 2019; 55(1): 1-3.

4. Jeffreys, I., Huggins, S., and Davies, N. “Delivering a Gamespeed-Focused Speed and Agility Development Program in an English Premier League Soccer Academy.” Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2018; 40(3): 23-32

5. Delgado-Bordonau J.L. and Mendez-Villaneuva, A. “Tactical Periodization: Mourinho’s best-kept secret?” NCAA Soccer Journal. 2012; 6: 29-34.

Confessions of an Instability Buff (and How I Now Train Balance for Sport)

The concept of unstable surface training blew my mind back in the late 2000s. To help pay tuition while I was finishing up physio school, I was training at a big box gym. At that time, it seemed to make so much sense as a way to improve an athlete’s balance and, ultimately, their performance. If they can do it on an unstable surface (which is harder, right?), then I would surely be setting athletes up for huge results.

I was young and excited, and I threw everyone who would let me train them and their mother onto a Bosu ball, balance disc, or physioball. The more complex and unbalanced the activity was, the better. The clientele loved it! If you were training during this period, I am sure you had someone at some point on a balance disc, an Airex pad, or some other sort of unstable surface. Everyone was doing it!

Need to get “toned” for your wedding? Bicep curls while standing on one leg on a Bosu ball is the answer—while your arms are toning, so are your legs. It’s functional!

Want to play golf in college? Working on rotational drills while standing on a Bosu ball or half foam roll is the key. If you can swing and stay balanced on the unstable surface, then you’re going to crush the ball on the course because the ground doesn’t move!

Want to play basketball in college? We definitely need to do all of your work on a physioball and Bosu ball, so you have to use your glutes and entire body to stabilize while you get strong. No way you sprain your ankle now!

I was a genius…and everyone in the gym was blown away by my creativity. They loved that it was new and different. I had a long waitlist of clients to train with me because of a serious case of FOMO.

Unfortunately, my professors in physical therapy school didn’t help curb my “genius.” Evidence-based practice was all anyone talked about, and they were focused on all the great rehabilitation literature that came out at this time.

There were studies that showed proprioceptive training allowed athletes to improve static and dynamic postural control. It not only could have important applications for preventing injuries such as ankle sprains and knee injuries, but might also improve sports conditioning parameters.1 When you read a bit deeper, however, those “sports conditioning parameters” likely didn’t really mean anything for your athlete’s sport. Back then, though, I missed that important part.

This research was very exciting, as it seemingly gave us a way to improve an athlete’s ability to recover balance after an injury. The research also seemed to suggest that there was a possibility of preventing injury by incorporating proprioceptive training into an athlete’s regimen. Remember this research for later in the article as I’ll come back to it.

As if this wasn’t enough, all the EMG studies furthered our obsession with how great unstable surface training was. I can’t remember a single class in physical therapy school where an EMG study wasn’t brought up in support of a reason to do a specific exercise because it “increased muscle activation.”

EMG – More Activation Doesn’t Always Mean Better Outcomes

There are numerous studies out there that highlight the increase in muscle activation levels when you train someone on an unstable surface. These studies particularly highlight the deep core and the other “stabilizing” muscles. They point out which specific exercises on unstable surfaces elicit the highest activation levels in specific muscles.

This research was great for those of us looking to hit specific muscles or areas to train up performance and do it via unstable surface training. The research seemed to support that we were doing the right things and that unstable surface training was a viable option. Unfortunately, as I came to realize later in my career, I was just looking at research and data long enough and in enough different ways to tell me what I wanted to hear. I was not critically and objectively reading the research: unfortunately, I was cherry-picking it.

The research seemed to support that we were doing the right things and unstable surface training was a viable option. Unfortunately, I was cherry-picking the data. Share on XWant to target the obliques more than the rectus abdominis because your athlete has a serious deficit there? Have your athlete do a crunch on a physioball instead of a traditional crunch, as the research shows increased oblique activity with this variation (and decreased rectus activation). I’m not sure how or why you would assess this objectively for sport performance, but the research says you can train those obliques up if you want to!

Fast forward a decade. Today, I have quite a different lens through which I attempt to evaluate all this.

As someone who works exclusively with rotational power athletes and has taken a deep dive into the research, I know this is where the caution flare needs to be shot up for all coaches and physios when it comes to EMG studies and the subsequent unstable surface training that has been touted for over a decade. The gluteus medius is probably the most famous EMG target and my personal favorite. If you are a coach or physio, you have definitely said or heard the phrase “we have to get your glutes firing.”

It made its way through the physio ranks and into the mass media spotlight when Tiger Woods told the world his “glutes weren’t firing” after a round of golf in the mid 2010s. After Tiger said he needed his glutes firing, I am sure the sale of minibands skyrocketed for those abduction walks!

If we stop to think about this for a second, however, obviously his glutes were not paralyzed…they were doing something, right? If they weren’t, how would he have been able to walk and how was he swinging the golf club over 120 mph? This is where my head went, and I hope yours does as well.

This Misunderstanding of EMG Research and Unstable Surface Training

Through all of my research digging, I was unable to discover where the idea of needing to train the deep core and stabilizing muscles even came from. My best guess is that it’s from the rehab world, though. I did find that researchers in one study were unable to find any diagnosis or articles reporting selective deficits of core muscles in strength-trained athletes. They went on in their article to discuss how confused they are about what data even led to the demand for specific exercises to strengthen the deeper trunk muscles, in particular, or improve the ability to selectively activate them. Furthermore, they were unable to find any evidence that classical strength-training exercises (e.g., squat, deadlift, snatch, and clean and jerk) affect only “global” muscles or lead to imbalances between the muscles of the trunk.2

This was of particular interest to me as I dove deeper down this unstable surface training rabbit hole. Wasn’t that the whole reason we had people doing unstable surface training in the first place? We wanted to target those deep stabilizers that did not get hit as well in traditional strength training, right? This only further confused me as to why we all started training this way in the first place. Perhaps it was nothing more than our innate desire for something new and exciting? I kept digging.

Electromyography has traditionally been used to measure changes in externally measurable force. Muscles used to aid in joint stability can contribute significantly to electromyographic signals without altering measurable force.3This means, simply, that you can increase how much muscular activity an EMG will read in a specific muscle group by having an athlete do something in a different way, but without it necessarily being in a way that positively impacts sport performance. For example, that’s great that your gluteus medius fired 20% more on the balance disc, but did you hit the ball farther or straighter afterwards?

While you’ll naturally see increases in the stabilizing musculature activity when someone is on unstable surfaces—does it translate to performance? Share on XIf I have an athlete swing a golf club on a Bosu ball, they have to try not to fall down. To achieve this, there will often be increased activation of their glute med and other hip stabilizers. While there will likely be an increase in EMG activity in these areas, the question that I wanted to know was if they would swing any better? While you will naturally see increases in the stabilizing musculature activity when someone is on unstable surfaces, particularly in the ankles and hips, the only question that matters is “Does it translate to performance?”

Somewhere along the line, people decided to circumnavigate the final connection to performance and instead moved past GO, collected their $200, and jumped to the conclusion that unstable training improves performance because it increases muscle activity. Hence, we arrived at “If you train golfers to swing on unstable surfaces, they will be better for it.” Born at this point was Golf Digest’s Dustin Johnson swinging a golf club while standing on a physioball—classic.

The belief was that having a golfer’s “stability muscles” firing at a higher rate would transfer to better performance because they would be more stable. If we accept this level of clinical reasoning, we should be putting all of our golfers and athletes on unstable surfaces because it increases neural drive to the stability centers, which is the key factor for performance.

The problem with this line of thinking, unfortunately, is that it fails to read the next line in much of the research that addresses the impact on performance of all this increased activity in the stability centers. Above and beyond what would be necessary on the stable ground where the game of golf and many other sports are played, the benefits of unstable surface training dissipate. The increased training of these stability centers has a point of diminishing returns and has even been shown to decrease an athlete’s ability to produce power.4

The flare of caution on EMG studies is one of paralysis by analysis. I believe the lack of applicability to performance actually gets lost in all of the numbers and confusing scientific terms of analysis. All of this EMG information is nice to know, but its applicability and usefulness in the training of high-level athletes is questionable at best. Coaches training high school, collegiate, and professional athletes would be better off if they forgot EMG studies exist on unstable surface training.

Coaches training high school, collegiate, and professional athletes would be better off if they forgot EMG studies exist on unstable surface training. Share on XAt the end of this deep dive into the research surrounding unstable surface training, EMG studies appeared to make up a large percentage of the studies that people would use as rationale to train specific muscles and areas. The EMG argument for unstable surface training loses its steam when you view it in the context of sport and performance. Performance happens in uncontrolled environments on stable ground and requires large amounts of power output in most sports. In most cases, EMG studies on unstable surfaces occurred in controlled environments on unstable surfaces with diminished power outputs.

Rehab vs. Sports Performance Applications

This is where the real discussion of this article begins, and we need to start by drawing a vivid line in the sand.

Unstable surface training has been shown to be useful in rehab settings to improve proprioceptive skills and capabilities. That’s it. There are clear positive medium- and long-term effects to proprioceptive measures reported in studies when the athlete is not acutely fatigued from proprioceptive training.1

Unstable surface training has been shown to be useful in rehab settings to improve proprioceptive skills and capabilities. That’s it. Share on XUnstable surface training has not shown value in sport performance training for rotational power athletes or any other power athlete and actually has been shown to be detrimental.

That’s the line for where unstable surface training is applicable and helpful. Hopefully, that’s clear enough. Let’s go deeper into the discussion about unstable surface training in the weight room.

Unstable surface training actually should be used with caution in the weight room because it produces short-term negative performance outcomes due to proprioceptive fatigue.1This means that if a coach preceded heavy power work with intense proprioceptive training, they could actually increase the chances of injury to the athlete because their proprioception would be acutely worse. Coaches and physios should, however, make sure to stress an initial warm-up on stable ground such as a traditional dynamic warm-up, as this showed a general improvement trend in the control group of this study1.

Leave the Airex pads and balance discs in the closet and avoid unstable surface training as part of your warm-up with your athletes. Keep the dynamic warm-up on stable surfaces and you will set up your athletes to perform better in their workout.

In another study, unstable surface training was found to lower maximum strength and muscle activity in deadlifts. In this particular study, it did not increase performance, nor did it provide greater activation of the paraspinal muscles.5The deadlift is one of the most important lifts for golfers to develop strength in, and if you extrapolate these findings to other lifts, it makes you question further the value of unstable surface training to performance in other exercises.

To further this deadlift finding, another study looking at unstable versus stable surface training found that there is a mean force deficit of 29% with unstable surface training compared to similar stable training surface exercises.6This is HUGE! For those of you training higher level athletes, putting them on unstable surfaces trains your athletes to produce less force. Not an ideal scenario.

For those of you training higher level athletes, putting them on unstable surfaces trains your athletes to produce less force. Not an ideal scenario. Share on XTo be objective, a number of studies have found equivalent output or no difference in strength outcomes with unstable versus stable training with strength and power markers. To be fair to the faction of physios and coaches who use unstable surface training regularly, it does work, and this is for you! But—and this is a big but—these studies were only done on relatively untrained or older adults, not high-level athletes. Remember, higher level athletes saw decreases in performance when using unstable surfaces, likely due to the, on average, 30% less force created.

This research, in my opinion, is not applicable to the sport performance world, but rather the general fitness and rehab worlds. If you work with seniors or other untrained individuals where you would not recommend higher level loads anyway, there appears to be an equal benefit to unstable and stable surface training on strength gains and power gains. I would call this the “newbie gain” phenomenon. No matter what you give them, they will get better.

There is a threshold, however, where the law of diminishing returns sets in for unstable surface training and it actually starts to become a detriment as shown in the research. It is up to us as professionals to identify where that threshold is and implement appropriate progressions. If you regularly test and retest your athletes, identifying these sorts of negative changes should be simple.

I see this threshold being crossed a lot with our adult golfers who come out of rehab from other locations. Many physio clinics do not progress their patients beyond unstable surface training and low-level TheraBand training. This leads to many recreational athletes and golfers still using low-level training and unstable surface training months and even years later. Because they are not progressed beyond the initial newbie threshold, many of them have significant strength deficits relative to the demands of golf or other sports they enjoy. This, unfortunately, leads to them facing subsequent repeated overuse injuries due to low resilience.

I am guessing, however, that most people reading this are not looking to train “average.” You are looking to train elite athletes who will perform at extremely high levels and require significant stimulus to see training improvements. If this is the case, unstable surfaces are not your answer…emphatically. In fact, they are your anti-gain, as demonstrated by decreased power outputs in elite level players when training on unstable surfaces.4

If you train elite athletes who will perform at extremely high levels and require significant stimulus to see training improvements, unstable surfaces are emphatically not the answer. Share on XDespite the research, golf fitness professionals and golf teaching professionals hold deeply to their personal need to work on “stability” in their golfers. And no one will argue that stability in the golf swing is important. The challenge is that the solution in golf workouts is often to use unstable surface training. Because of this, I wanted to dedicate an entire section of this article to this topic.

Training Stability and Balance in Golf

If you have been in or around the game of golf, you have undoubtedly heard people talk about the importance of stability and balance in the golf swing. These aren’t novel concepts or unique to the sport of golf.

What you have not likely heard is a unified consensus on how to best train those traits. You also have not heard how to objectively measure and define what balance and stability is in the golf swing. This is where the problem starts.

On the instructional side, many golf instructors have taken to having students hold different positions in their swing on half foam rollers, balance discs, or other unstable surfaces. This makes sense to them, as they operate under the same logical line of thinking that I did when I started training back in the late 2000s. If they can get the athletes to be “stable” at the top of their swing or impact and “feel the position,” it surely will be easier for them when they are swinging full speed on stable ground. As we saw earlier, this line of thinking is severely flawed.

There is often a huge emphasis on “turning golfers’ glutes on” in the golf swing and activating all sorts of scapular muscles, etc. It is not uncommon to hear a golf instructor tell a golfer to turn their glute med on in the back swing and/or really fire their serratus anterior on the trail side during the downswing. Oh, and simultaneously fire the infraspinatus and teres minor on the lead arm through impact to make sure you finish your release. I am not sure how this all became so ingrained in the line of thinking in golf performance. I suspect it came from the rehab world, where we physios are famous for having athletes do clamshells until their glute medius doesn’t function anymore and then telling people to “squeeze their glutes” when they walk.

At any length, we all know that internal cues are the absolute worst thing to give an athlete to think about when it comes to performance. The best instructors in the world totally understand cueing and everything that goes with it, but they are the minority, unfortunately.

Playing basketball in college, I can’t imagine my coach telling me to fire my glutes when I took a jump shot or jumped for a rebound. That’d be crazy. Yet, that is what many golfers get during their instructional lessons every day across the country.

Again, if it looks like a golf swing, it has to be good for the golfer—until you dive into the research. Share on XIn the golf fitness world, much from the influence of this line of thought, the idea of training balance and stability just morphed into putting a weight in someone’s hand or giving them a cable to rotate with. Again, if it looks like the golf swing, it has to be good for the golfer—until you dive into the research.

We see all sorts of examples of this on social media, in major golf publications, on the Golf Channel, and even in the warm-ups and workouts of the best players in the world. In most cases, I have noticed one of two extremes when it comes to “golf fitness” training.

On the one side of the spectrum is what I call the “Mystical Physio.” This approach is where athletes are trained with little more than a band in all sorts of fancy PNF and other neuromuscular approaches. The golfer (and coach) are afraid of the golfer getting hurt and so don’t use heavy weights. The claim is that they are training neuromuscular firing patterns to maximize efficiency and stay flexible. Ironically, this leads to golfers having poor resilience to the rigors of Tour travel and demands, and increases the likelihood they will be hurt. On a sad note, I have seen this approach be the death of many careers for hypermobile golfers whose only hope for longevity was getting stronger.

The other side of the spectrum is what I call the “Tortured Trainer.” We all know one. They can’t go a week without making up a new exercise and posting it all over social media to show how creative they are. There are always lots of comments about how awesome the exercise looks and how people can’t wait to try it out. The buzz builds, especially when it is a top Tour pro doing it, and next thing you know, all the golfers in the world are incorporating it into their workout.

A recent example I saw of this could only be described as a rear foot elevated jump and land in place with the rear foot elevated stance maintained, followed immediately by a rotational medicine ball throw. You might have to read that three times, but it is the simplest way I can describe what I saw. The issue here is the confusion created from adding too much complexity. The exercise often grows so complex that the skill it was originally intended to train (assuming rotational speed or single leg balance or single leg strength?) becomes so washed out that it is minimally effective, if at all.

Looking back on my early training experience while I was finishing up PT school, I was crushing the commercial gym scene with the “Tortured Trainer” approach. I wasn’t actually good at training people or writing programs to help them meet their goals. But I had a long client list as long as people liked me and were intrigued by what I was doing. The problem with this was that I had to keep making up new stuff to keep them interested and none of it was based in any sort of science or objective measure. It wasn’t sustainable and if I had measured, they probably wouldn’t have been as impressed.

Early in my physio career, I made the transition to the “Mystical Physio” approach—attempting to improve people’s movements with primal movements, rolling, minimal hands-on work, and nonexistent strength training. Again, I had a long client list and people actually thought I knew what I was doing. If I’m honest, I hit plateaus with many clients. (Basically, when they needed serious hands-on work or real strength training that I wasn’t doing).

In both cases above, I missed the middle ground and I had to learn it the hard way. Sometimes it is appropriate to add complexity to an exercise and other times neurological retraining can be magical. But neither one is ever the answer in isolation, and if you do too much of either, the results are counterproductive. They are all part of a larger training and rehab continuum; just as unstable surface training is. The more of us that can realize this, the better it will be for our athletes.

The golf performance world is improving every year and the research on unstable surface training is hopefully becoming clearer with this summary. No matter the sport or the athlete, the first place to start is always an individual evaluation to understand the demands of the sport and how well the athlete is prepared to meet those demands at a high level and without injury.

Regardless of your feelings on the above, we can all agree that the buck stops with performance on the course, field, or court.

Transference – Is It There?

At the end of the day, all of the research, training philosophies, and ideas in the world come down to one question: Does it transfer to sport? That is all that matters.

At the end of the day, all of the research, training philosophies, and ideas in the world come down to one question: Does it transfer to sport? That is all that matters. Share on XIn the world of golf, in particular, this tends to be an oversight. We tend to focus more on the “why we are doing an exercise” and “does it look like it trains the golf swing patterns.” There is a serious deficit of focus on “does this intervention actually move the needle in performance on the course?”

Coaches applying unstable surface training with a proprioceptive training effect in mind may in fact be impairing the development of important athletic qualities such as power, speed, and force output.4Power, speed, and force outputs will be trained at about 30% less force output compared to using stable surfaces, which is likely the cause of the development impairment seen when unstable surfaces are used. This suggests that if we want to focus specifically on proprioception training, it should be done on stable surfaces to assure strategies and patterns used in sport are used in training.

Examples of proprioceptive work that would not be detrimental to power, force, and speed outputs would be having young athletes working on proper single leg stance mechanics on solid ground while passing medicine balls to each other versus standing on one foot on an Airex pad passing balls. A dynamic example would be single leg hops or box jumps with focus on stable landing and take-off mechanics.

In adolescents and young adults, the specific comparison of stable surface training and unstable surface training resulted in contradictory findings. Thus, the use of unstable as compared with stable surfaces during strength training is not recommended in healthy adolescents and young adults if the goal is to enhance performance on stable surfaces.7This means that unless there is a specific injury or physical deficit in proprioception, keep the unstable surfaces in the closet for your junior golf fitness classes and your sport performance training.

There have been a number of other studies that have shown a very high statistical correlation of chest pass power, vertical leap power, total rotational power, and others to club speed, which is a direct sport performance measure.8,9In lieu of the unstable surfaces, look at your programming and training to work on training up the skills to improve the physical traits needed to excel in these areas of power production.

What this all boils down to is that Bosu balls, physioballs, balance discs, and Airex pads should be kept in the rehab clinic. Train athletes on the stable surface they play on. Share on XWhat this all boils down to is that Bosu balls, physioballs, balance discs, and Airex pads should be kept in the rehab clinic. When the athlete enters the gym to train for sport performance, train them on the stable surface they play on. In the world of golf and most other sports, that means the ground (unless, of course, they surf or skateboard—then it is likely a different scenario). If you want to train stability and proprioception in the gym, do it on the ground and add proprioceptive challenges in terms of stance widths, external upper extremity challenge, and the like.

The next time you see a colleague having an athlete jump from Bosu ball to Bosu ball or integrating unstable surface training with high-level athletes’ performance programs, please initiate a constructive conversation to improve both of your practices. We need to work together in the sport performance world to help coaches and athletes understand that adding complexity to an exercise to make it look new and different doesn’t always equate to improved performance. We need to challenge ourselves and our colleagues to keep to a higher standard—one of measured transference to sport performance.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Romero-Franco, N, Martinez-Lopez, EJ, Lomas-Vega, R, Hita-Contreras, F, Osuna-Perez, MC, and Martinez-Amat, A. “Short-term effects of proprioceptive training with unstable platform on athletes’ stabilometry.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2013; 27(8): 2189-2197.

2. Wirth, K, Hartmann, H, Mickel, C, Szilvas, E, Keiner, M, and Sander, A. “Core Stability in Athletes: A Critical Analysis of Current Guidelines.” Sports Medicine. 2017; 47(3): 401-414.

3. Behm, DG, Leonard, AM, Young, WB, Bonsey, WA, and MacKinnon, SN. “Trunk muscle electromyographic activity with unstable and unilateral exercises.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2005; 19: 193-201.

4. Cressey, EM, West, CA, Tiberio, DP, Kraemer, WJ, and Maresh, CM. “The effects of ten weeks of lower-body unstable surface training on markers of athletic performance.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2007; 21(2): 561-567.

5. Chulvi-Medrano, I, García-Massó, X, Colado, JC, Pablos, C, de Moraes, JA, and Fuster, MA. “Deadlift muscle force and activation under stable and unstable conditions.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2010; 24(1): 2723-30.

6. Behm, D and Colado, JC. “The effectiveness of resistance training using unstable surfaces and devices for rehabilitation.” International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2012; 7(2); 226-41.

7. Behm, DG, Muehlbauer, T, Kibele, A, and Granacher, U. “Effects of strength training using unstable surfaces on strength, power and balance performance across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Sports Medicine. 2015; 45(12): 1645-1669.

8. Finn, C., Prengle, B. and Cassella, A. Research Driven Golf Performance Training, Par4Success. October 2018, pp. 3-20.

9. Finn, C., Prengle, B. and Cassella, A. Eccentric Flywheel Training and Its Effects on Club Speed in Golfers: A 6 Week Study. Par4Success. April 2019, pp. 2-10.

Considerations for the Director of Sports Medicine & Athletic Performance

As a result of the recent tragedies that have transpired in collegiate athletics, there appears to be an increased push by many institutional administrations for the elimination of athletic department “silos.” This coordinated integration of various independent athletic departments is an attempt to cultivate a more homogenous organization. At various higher education institutions across the country, such a merging has begun to eliminate the segregated configuration of the medical (i.e., athletic training) and athletic performance (i.e., strength and conditioning) entities into one unique “Athletic Performance” model.

Throughout my professional career, I have had discussions with members of professional sport organizations, as well as higher educational institutions, with regard to the establishment and/or continued development and management of this type of athletic department model. During these conversations, the most frequent inquiry has been: “What type of professional is qualified to lead this new model, and what are the occupational requirements?”

The commencement and management of such an athletic performance type model will require a very skilled and unique professional to assume the director’s role. As a “formal” organizational structure is beyond the scope of this blog, this dialogue will present both thoughts and guidelines for six simple strategies for the athletic performance director (APD), based on my experience as a business executive, sports rehabilitation provider, and head strength and conditioning coach. It is important to reiterate these are only guidelines offered to the reader, as there are no absolutes, so to speak. Every institutional state of affairs has its own unique concerns.

Is the Individual Candidate Qualified for the Athletic Performance Director Position?

Professionals working in their specific occupation of choice often have aspirations to eventually achieve a supervisory role. Stating the obvious, the APD should have a noted background of experience in the two diverse yet inter-related professions of sports medicine/sports rehabilitation and athletic performance enhancement training. At a minimum, they should have an extensive background in one of these vocations, as well as an extensive appreciation of the complementary profession. Optimal success for this model cannot be dependent upon an expertise in a single professional “silo” of experience.

The APD must possess the knowledge proficiency and key technical skills to both assist and advise this new model’s team. It should also be acknowledged that a weekend course and accompanied certificate of completion do not create an “expert” in any professional field of choice. The APD is the “conductor of the athletic performance orchestra” and, thus, should have a strong familiarity with all of the instruments necessary to attain the harmony desired.

The APD should also have supervisory and proven leadership experience. The ability to lead a team of professionals, organize, interrelate, and communicate—as well as work with other managerial heads and departments including, but not limited to, general managers, athletic directors, head coaches, medical (including team physicians), strength and conditioning, technology, research, video, finance, legal, compliance, etc.—in a positive manner is imperative. Just as a head coach and their team of athletes require the cooperative and coordinated efforts of all assistant coaches, senior administration, and integral related departments, so does the APD and their staff.

Don’t underestimate what a critical asset leadership is for those taking a director or senior management level role. Don’t confuse it with job proficiency and/or management abilities. Share on XLou Carnesecca, my former Head Coach at St. John’s University of New York (and in the Basketball Hall of Fame), and NFL Super Bowl Champion Coach Dick Vermeil both instilled in me this significant message: “The players and staff don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.” Leadership is a critical asset for all those assuming a director or any senior management level role and should never be underestimated.

This unique quality should not be confused with job proficiency and/or management abilities. The ability to perform a job well or to manage others does not directly correlate to exceptional leadership abilities. Leadership is the ability to positively influence staff and peers while simultaneously achieving the outcomes desired. This is an assumed yet often lacking quality, as demonstrated by the fact that many prominent assistant coaches have failed to establish themselves as leaders after assuming the role of head coach.

The APD should always be motivated to roll up their sleeves and work side-by-side with their staff, treating each individual staff member as a person and not an object or number. The staff should feel comfortable voicing appropriate opinions and conversations. All new staff additions should be made to feel welcome and at ease with their transition into their new department role. It should also be noted that there is a big differentiation between leadership and standing behind someone and “pushing them forward” via the scare tactics of bullying and intimidation. These destructive strategies are not only negative and demoralizing, but they may eventually become catastrophic as well.

It is important not to confuse the enactment of process with the achievement of results. Share on XThe APD should also be able to identify presently established as well as absent essential department needs, including the advancement, expansion, and implementation of the required processes for the vision and culture of this “new” department model. That said, it is important not to confuse the enactment of process with the achievement of results. Recognition of individual and department competencies, as well as insufficiencies, will help the APD make appropriate decisions for the sustained success of both staff and department.

Knowledge, skill, and role progression for the department as well as individual staff are essential for the retention of excellent staff. Failure to do this will result in stagnancy and regression, while the competition will likely continue to effectively progress forward. Thus, process and educational strategies for continued staff development in knowledge and skill proficiency, as well as valid objective testing to quantify all department strategies, must be employed. Objectivity is fundamental: If “x” is not measured, “x” will not likely change. The APD must also heed department financial budgets and adhere to project timelines. Failure to comply will derail progression and often results in a failure to achieve significant plan objectives.

Don’t forget that the establishment of this new organizational model and director role, as well as any department staff position, is entirely for the benefit of the athlete. Share on XLastly—and this should never be disregarded—the establishment of this new organizational model and director role, as well as any department staff position, is entirely for the benefit of the athlete, not for the advantage of any department, staff, or employed individual. Therefore, the ADP must also demonstrate the ability to relate to the athlete and their environment and prioritize the department’s obligations to the athlete in regard to medical care and athletic performance development.

Does the APD Have a Proven Organizational Model Structure?

The potential director should disclose prior success in an organizational model, philosophy, and culture as evidence to heighten the medical care and performance enhancement training of the athlete. This defined model must also positively correspond to the parent organization model. Considerations such as the number of department professionals to be employed, the variety of specific professional vocations (i.e., athletic trainers vs. performance coaches vs. nutritionists vs. additional health care professionals, etc.), and the necessary qualifications for both staff and supervisory roles are examples of some of the multifaceted assessments to be determined.

Additional considerations include, but are not limited to, the evaluation of the present-day department’s staff and existing operational methods employed to the athlete; evaluation of the medical and training facilities, equipment, and supplies; and the noted processes presently employed and intended for future implementation, as well as those to be eliminated. The APD should also be aware of the associated departments of the parent organization that are accessible to assist in the success of this new model.

The establishment of an appropriate department culture is most essential, as all staff must commit to the same medical and athletic performance philosophy, implemented process, work ethic, and goals. As NFL Hall of Fame Coach Bill Parcells has taught me, “there is a big difference between routine and commitment.” Department leaders and staff cannot “do their own thing” nor “R.I.P.” (rest in place), as a strong commitment is required for all implemented processes and programs to result in the successful attainment of all objectives.