Keir Wenham-Flatt is Coordinator of Football Performance, a role in which he oversees all aspects of the physical performance training of William & Mary’s football student-athletes. His duties include weight-room-based strength and power development, speed, agility, conditioning, and close integration with the football staff to monitor training load, offer sport science insights, and assist in the management of the training process.

Wenham-Flatt came to W&M after working within professional rugby for nearly a decade in five different countries: the U.K., Australia, China, Japan, and Argentina. Among his career highlights are a fourth-place finish at the 2015 Rugby World Cup with Los Pumas Argentina and a 2014 World Club Challenge win with Sydney Roosters Rugby League. He also provides leading performance education with his work at the strengthcoachnetwork.com for those interested in expanding their knowledge base.

Freelap USA: You are now working in American football. Can you share what you have learned from the U.S., and how you use what you have learned from rugby to make athletes better? Obviously, a lot of overlap exists between the two sports.

Keir Wenham-Flatt: I’ve had the good fortune to work in several different countries now for varying periods of time, and each of them had something they did better than anyone else and could teach the others. For Australia, it was the monitoring and management of workload. The U.K. spends a lot of time cultivating and developing youth talent at the professional level. The centralized and single-minded Chinese system (morality aside) speaks for itself. And to be a part of the Argentinian culture and passion was an absolute privilege.

Undoubtedly, the Americans are world leaders when it comes to good old-fashioned strength and power development. The academic, collegiate, and professional development systems here have produced legions of coaches who are extremely competent and comfortable at developing big, strong, powerful athletes. A 500-pound squat is usually something to write home about in professional and international rugby, but it might not crack the top 10 for a mid-major college football team!

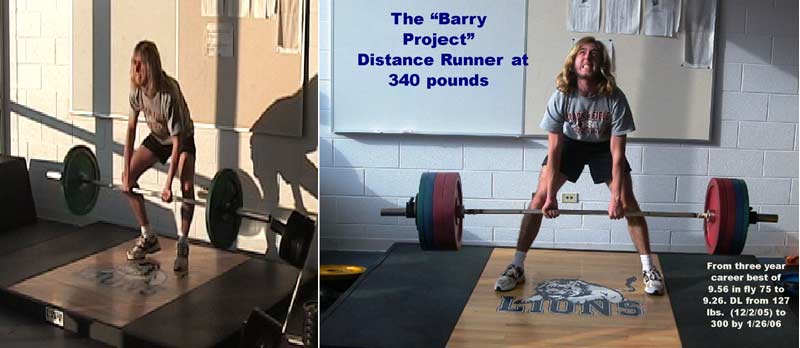

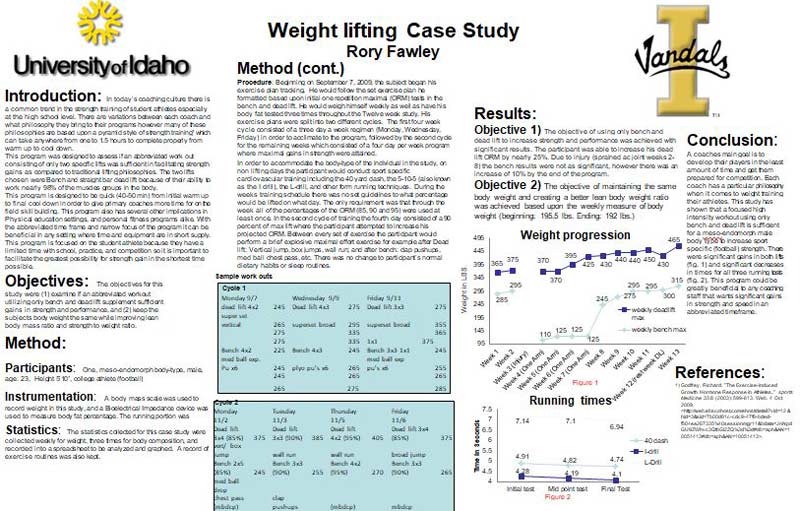

We encourage our athletes to always think working backward from game demands and to understand that weight room numbers are just a means to an end, not the end itself. Share on XAs with all things, though, the better we are at something, the more we lean on it and perhaps neglect other areas. If I’ve been able to bring something new to my role at William & Mary with my colleague Dr. Erik Korem, it is perhaps to adopt a more holistic approach to our athletes’ development. We encourage our athletes to always think working backward from the game demands and to understand that weight room numbers are just a means to an end, not the end itself. If we don’t see noticeable improvements in the intensity or repeatability of sporting skill on the field, we’ve wasted our time. It is obviously a work in progress, but we felt like we were turning a corner when skill guys were bragging to one another about their fly 10 times as much as their bench.

Freelap USA: As someone with a reputation for creative solutions for training, how do you scale your methods to large teams such as college football? Clearly, it takes more than just altering workouts.

Keir Wenham-Flatt: With difficulty! Obviously, we would love to train each guy like a snowflake and give the right stimulus, right time, and right amount for every session. But this approach is incredibly resource-intensive and just not viable, particularly at the FCS level. Instead, we try to take a Dan Pfaff “bucket” style approach—broad categories where guys with fairly similar needs will be placed at each stage of the program. This is based on a list of factors including, but not limited to:

- Training Age: What it takes to move the needle for a freshman compared to a fifth year is very different. The freshman just needs to look at a bar and he’ll adapt, whereas the vet needs to be extremely precise.

- Athlete Qualification: As a case in point, we’ve just enrolled a freshman who in high school was a state champion 300 hurdler. He has never touched a weight in his life and is already 206 pounds in the single-digit body fat range. In terms of lean body mass, he is probably already where he needs to be, so he will receive quite different training to the archetypal undersized freshman who needs to spend a lot of time under the bar and at the dinner table.

- Injury History and Anthropometrics: We have maybe 5-6 guys who just don’t seem to gel with traditional back squats or trap bar deadlifts despite our best efforts, so we work around this with less irritating variants. We are not married to any particular exercise. Our primary goal is that the guys are healthy, feeling good, and doing something close to the original exercise that we can load up and adapt to.

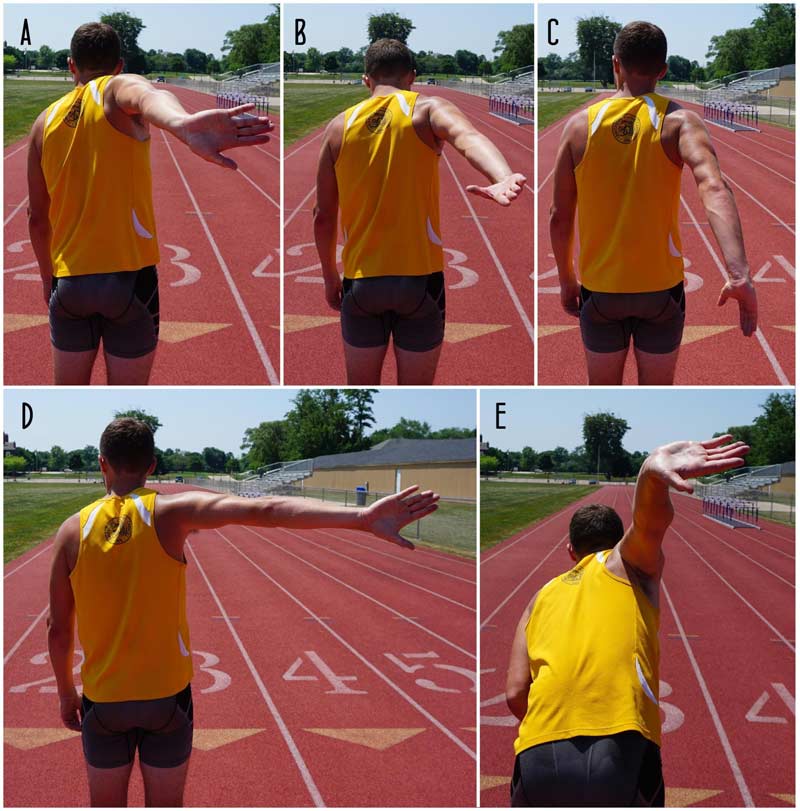

- Position: We work off the “postcard test.” If I were to write down on a postcard what it is you do better than anyone else on the field or what the best guy in the world in your position does best, THAT is what we need to train to enhance. The answer to that question will be extremely different for a receiver (Vmax sprinting, cutting and running, vertical jumping) compared to a defensive lineman (pass rush, hand fight, and tackle), which informs our exercise selection, particularly when general means have ceased to transfer.

- Honestly… Staff: When we have sufficient staff and interns on deck, with lower player numbers per session, we have more ability to individualize what we are doing. During some chaotic times in the year, though, we have to simplify what we are doing. Not ideal, but a well-organized and well-executed general program performed with good atmosphere is better than herding cats.

Freelap USA: Education is everything for a developing coach. Can you explain why your online modules are valuable for coaches who are still getting started, as well as for veterans? With so many options, why is strengthcoachnetwork.com still a leader today?

Keir Wenham-Flatt:Well, first off, I’ll say that I am a huge fan of seminars, conferences, and other in-person workshops. I can trace back key stages in my development as a coach to events like these. The side conversations, introductions to other coaches, and exposure to ideas or topics you didn’t know existed are all invaluable.

But there are drawbacks to such events—cost, for one. If you wanted to attend a clinic every month, it would run you or your school several thousand dollars per year, minimum. What happens if you decide that 80% of the talks aren’t for you? You’re paying for information you don’t want to consume. What if you suddenly think of 10 more questions for the speaker, but in the hustle of the event you don’t get to ask them?

Whether you like it or not, the reality of our profession is that those who get ahead are strategic in their career planning, says @RUGBY_STR_COACH. Share on XOur goal with strengthcoachnetwork.com was to fill the gaps left by the traditional continuing professional development circuit. We offer low-cost, high-quality educational video lectures ONLY by coaches working at the elite or professional level of sports. You can ask the speakers as many questions as you like, discuss topics with members from all over the world, and (my favorite section) get advice on career development and the business side of coaching.

Whether you like it or not, the reality of our profession is that those who get ahead are strategic in their career planning, and robust enough to withstand the financial vagaries of coaching. The thing I am most proud of on the site is the number of people we have been able to help secure interviews, internships, jobs, and a little more financial security in their careers.

Freelap USA: You obviously know how to develop power in the weight room without the use of Olympic lifts. Instead of just going into the reasons why you choose to apply alternative means, can you explain what both users and non-users can learn from general principles of training? You have a very effective speed program that is the core of your training; perhaps you can share how speed and power interact outside the field or track?

Keir Wenham-Flatt: A useful analogy for the prescription of strength and power training is administering a drug. The loading parameters of the exercise—range of motion, peak production within that range, musculature, magnitude and direction of force, angular velocity, contraction type, energy system, sensory information, etc.—these are the “drug” that chiefly dictate how the body will respond. The exercise is just the method of delivery. Intramuscular injection of a painkiller will have broadly the same effects as oral ingestion or the dreaded suppository.

A useful analogy for the prescription of strength and power training is administering a drug. The exercise is just the method of delivery. Focus on the drug more than the delivery. Share on XI would encourage coaches to focus more on the drug itself than the method of delivery. As long as you are hitting the big-ticket items of dynamic correspondence as laid out by Professor Verkhoshansky, you should be good. Through my own reflections and trial and error, I’ve concluded that what truly makes the Olympic lifts “special” is that they recruit a ton of musculature and require rapid force production in triple extension, and there is little to no inherent deceleration of the bar associated with regular exercises like squats or deadlifts.

As long we achieve these via other means, I am not sure it matters too much, despite the efforts of Daniel Martinez to persuade me otherwise in our discussions. A case in point: I trained our throwers this year. One sophomore male used the Olympic lifts throughout, PR’ed in the discus by several meters, and made the NCAA finals. Another female freshman did no Olympic lifts, also PR’ed in the discus by several meters, and broke the school record three times in a year. Many roads lead to Rome.

With regard to the interaction between speed and other elements, I defer to Charlie Francis. I have noticed, like he did—although I can’t prove it—that increasing maximal sprinting velocity appears to improve outputs across the board. Like a rising tide lifting all boats, pushing the envelope of what the CNS and neuromuscular system are capable of in terms of force, speed, and coordination appears to be extremely beneficial to barbell strength and power.

Freelap USA: Big efforts in power require big rest periods. How do you communicate the importance of rest to team coaches who may not understand sports science and the craft of strength and conditioning?

Keir Wenham-Flatt: Relationship above all else. Without mutual trust and respect, the foundation to change a coach’s or player’s mind and get them to abandon what may be comfortable or familiar is just not there. Once the relationship is there, logic, data, and framing the argument in terms appealing to what the guys want is key.

There is extreme cultural unease in football with resting for long periods. The belief that players must never walk or stand still is pervasive. But whether we like it or not, there are just hard limits to how the body works. You can’t try twice as hard to have a baby in 4.5 months. You can’t sleep faster and wake up after four hours feeling ready to attack the day.

Speed and power development requires several minutes of rest between efforts to achieve the kind of outputs that elicit adaptation. Our coaching decisions must reflect this. Share on XIt is a FACT about speed and power development that we are required to rest several minutes between efforts to achieve the kind of outputs that elicit adaptation. Players must understand that intensity has far more to do with the number on the stopwatch than how they feel. If we truly value speed and power, our coaching decisions must reflect this. Do not confuse business with effectiveness.

As coaches, we can sugar the pill by trying to make that downtime as productive as possible. If the guys have several minutes of rest to fill, we encourage sport coaches to go to the whiteboard and instill tactical concepts. Low-level static skill work like hand-eye coordination or walk-through is also acceptable. But the lower the intensity, the better.

From a tactical standpoint, we also have to appreciate that the context, timing, and speed of processing in sport comes from the intensity and speed of execution. FBS football averages 5 seconds in duration, with 35 seconds between plays, for an average of six plays per drive. After the typical drive, guys rest 11 minutes due to a combination of media, timeouts, half time, etc.

Now compare this to the typical camp situation, where guys may repeat dozens of plays back to back, with a fraction of the rest between series. Unsurprisingly, guys pace themselves to survive, the outputs drop as the session goes on, and the task of training grows ever more dissimilar to the demands of the game.

As my colleague Dr. Erik Korem argued, head coaches love to remark that “We look out of shape” during the first game of the season, and the reason is probably because they spent the whole summer training for a task that is nothing like the game. Poorly trained football teams might never achieve the kind of intensities seen in the game until game 1 itself. The more self-control you can exert during the summer and respect the rest periods, the faster you’ll train, the better you’ll engrain the necessary speed of technical and tactical execution and information processing, and the more dividends it will pay during the fall.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF