Mehh! Mehh! Mehh!

The alarm creates a cascade of cortisol, jolting me awake from a much-needed rest.

I check my phone—there’s no way it can be 4:30 already—but sure enough, it is.

To add insult to injury, it is pitch black outside. Not to mention, cold enough to turn my spit to string cheese as I hock when clearing my throat.

A warm shower would be nice. But it would soothe me, not “start” me. I pass on the hot water and instead, take a 10-minute walk in sub-zero temperatures to wake the hell up. Why? Because I’m a strength coach and gym owner. People like us do things like this, or so I’ve been brainwashed to believe.

Lucky me. It’s also the first of the month, meaning the gym gets paid today. Everyone’s credit cards and ACH get run. As I hear the crunching sound my shoes make on the snowy path, it reminds me of the sieve I’ve created for my bank account. The gym gets paid. The rent gets paid. The staff gets paid. And only then do I get paid, if you want to call it that. What’s left for me after taxes is pennies compared to the amount of work I put in.

“What the hell am I doing?” I mutter to myself. “I work so hard. Everyone is prospering except me. And I’m the damn owner!”

Sound familiar? This is the life of today’s strength coach and gym owner. Change is needed. And soon. Sooner than the day before yesterday.

While coaching athletes and seeing growth in your business is invigorating, it may come at a cost. Yes, you get fulfillment out of building relationships with each youngster who walks through your door. Yes, it is a damn good feeling to see your membership and monthly ACH increase each month. But while coaching and building a business, you are burning the candle at both ends, whether you know it or not.

If the grind this industry wears as a badge of honor is starting to wear on you, this article is for you. And if the work feels unrelenting, ruining any semblance of balance in your life, this article is for you. But if nothing changes, then nothing changes. More of the same leads to more of the same. And as a result, you may stay on the proverbial hamster wheel, or worse—want to leave the industry altogether. Call me crazy, but I believe you deserve to make not just a decent living, but a great one. This is exactly why I felt compelled to write this piece, so you can give up the grind.

Unfortunately, those who have paved the way for you now are blocking it. I may take some flak for this, but I know it is for your good and the betterment of the industry. The “old guard” preaches a do the work attitude day and night, saying things like:

- “If you’re waking up at 6:30 a.m., then you’re already too late.”

- “You need to decide if you’re going to be a business owner.” (Which means, “Your hobbies, workouts, and other things that fill you up need to be set aside.”)

- “If you’re going to try and be an expert then at least be in the game for five years first.”

If you would rather keep staring at your laptop screen until three or four in the morning because that’s what you were told to do in order to be successful, don’t let me stop you. However, if you would rather get in the driver’s seat of your life instead of daydreaming in the passenger seat, then follow and trust.

Imagine achieving financial freedom instead of living paycheck to paycheck. Imagine actually enjoying your mornings again rather than getting in the car half-asleep as you drive to the gym.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m all for hard work—trust me. But I’m also a huge advocate for doing nothing, and a lot of it. The irony in the latter is that when I find myself doing nothing—sprinting, reading, meditating, etc.—these are the times when some of my best ideas spawn. Then I can implement those new revelations into my deep work sessions, getting way more done in far less time.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m all for hard work—trust me. But I’m also a huge advocate for doing nothing, and a lot of it, says @huntercharneski. Share on XHaving owned a small private training facility for several years in West Michigan (excuse me, having a small private training facility owning me for several years), I’ve been where you’re at. But I also got out. My life is simpler now. I work way less and make more money than ever. Even when our small space served more than 100 athletes. But more importantly, I am helping others get off the hamster wheel and have some freedom, for Pete’s sake.

I live a bicoastal life now between Arizona and Michigan. I write every day. Some of that writing helps coaches and gym owners clarify their message, because most get embarrassed seeing their gym half-empty. Which results in working more hours and getting paid in frustration. And yes, I still coach. But I have built coaching around my life. Far too many do just the opposite. I can say, for the first time in my life, I am actually happy. And it didn’t take as long as you might think. Let’s break down how you give up the grind.

The “Go-To” Coach

Becoming a “go-to” coach for something is relatively easy.

I used to think becoming a “go-to” coach—much less, being seen as one—would take more than half my life to achieve. Not to mention, the knowledge one must have would be astronomical. But here’s something you won’t find in any university, textbook, or business class: in order to be seen as the authority on a subject matter, all you need to be is one chapter ahead of those you’re educating.

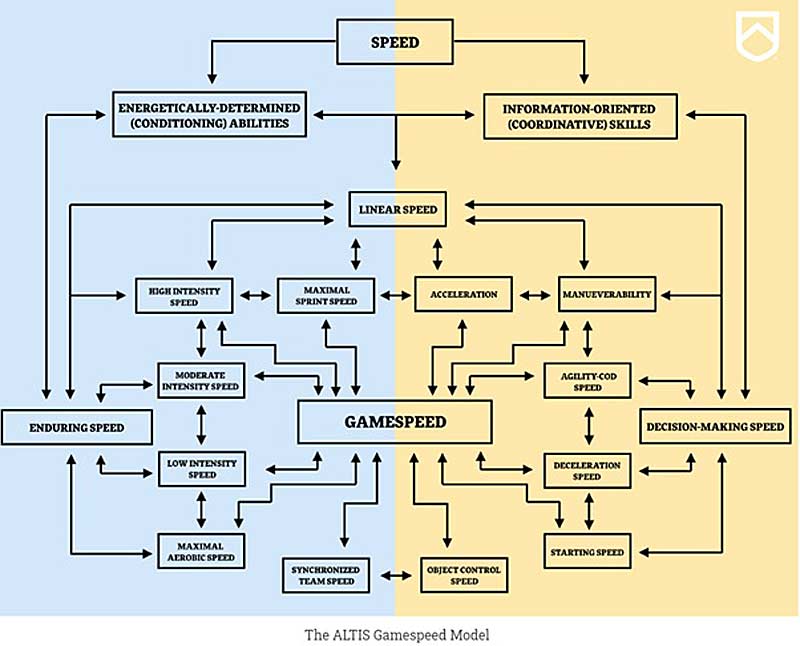

Toward the end of 2017, the subject matter I wanted to plant my flag on was speed. Sprinting and all things helping athletes “get there first” was a hot topic at the time. Having owned a facility in which we prided ourselves on the one biomotor ability everyone wanted more of, I had credibility at the micro-level. But I knew my “reach,” so to speak, would have to be at the macro.

Near the end of October, and with the new year fast approaching, I decided to host the first-ever #SPRINTORDIE Six-Week Speed Masterclass. (Some of you reading may have been part of it.) I would administer it in a private Facebook group. In the weeks leading up to the class, I posted an “Ask Me Anything!” story on Instagram. This was important for two reasons: anyone who asked a question was granted free access to the class, and the most frequently asked questions gave me insight into what people were struggling with. And thus, those questions became the modules for each of the six weeks (week one: drills; week two: footwear considerations; week three: hamstring rehabilitation; etc.)

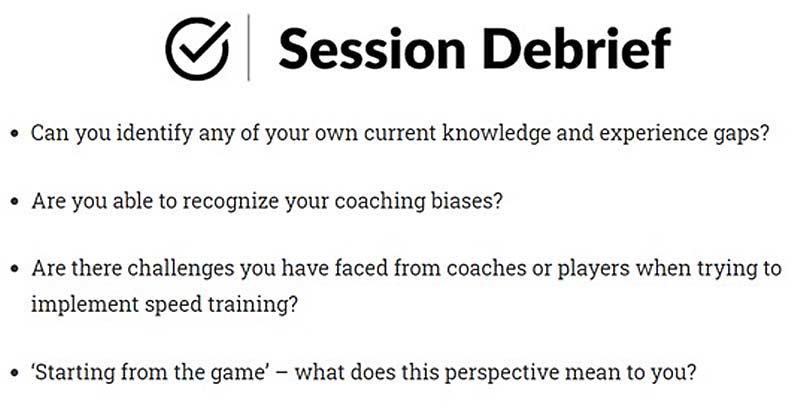

The class exploded. Having more than 50 coaches and practitioners in the group eager to learn from me was a huge boost in confidence—something that is incredibly important if you plan to be an expert. To buy myself more time for engagement with the class’s attendees, I pre-recorded all the modules via Microsoft PowerPoint with a Camtasia add-in. This feature allowed me to present each slide and lesson without losing the human aspect, as Camtasia provides a small space for the consumer to see your face on their screen.

In order to increase engagement in the class, I assigned homework at the end of each module. These assignments included their biggest takeaway, which was important. When you ask someone what their biggest takeaway was, or what was most helpful to them, they’re going to provide positive feedback. It’s an honest admission that you provided value to them. They, and you, start to slowly see you as an expert. I also asked people to share videos of their drills, runs, and sprints. They wouldn’t be vulnerable and post a video of themselves if they didn’t trust you, right?

Gather Social Proof

Serve first, sell later.

If you’ve read Influence by Robert Cialdini, then you know how strong the human condition for reciprocity is. Remember, I did not charge any of the attendees one red cent for the class. I was simply building trust, relationships, and most importantly, competence. At the end of the six-week class, all I asked the attendees was:

- “If you think what you got out of this class is worth more than $500, will you please provide a brief video testimonial of your experience?”

- “How could I make it better?”

Since these coaches had free admission, of course they were going to provide testimonials and suggestions for future classes. And they did.

Start a Side Hustle

Repackage your free offering and sell it.

Repackage your free offering and sell it, says @huntercharneski. Share on XWith the first class ending mid-February, I decided I would host another just weeks later in early March. I re-recorded the modules based on the suggestions the attendees made in order to deliver a better experience. And then with the dozen or so video testimonials I had gathered, and not an ounce of marketing experience, I started posting them.

Cialdini also touches on the power of social proof. When your prospective clients see others having success with your product or service (add a smiling face too for extra credit), they will be more likely to buy. And that’s all I did. I posted a video testimonial on Instagram and Facebook every Monday, with a direct call-to-action, and when next Monday came around, I would post a different video testimonial.

Wash. Rinse. Repeat.

As people started signing up, I added them to the Facebook group one by one. Once added, in order to instill more excitement, I asked them to tell the group what they were most excited about heading into this class. My goal for the first paid master class was 10 individuals. Nine signed up. The price tag? $597 each. More than $5,300 for six weeks. Not bad. I’d say the first class (which was free, remember) was well worth it. I would go on to host several more master classes before moving to the next chapter of my life. But let’s discuss what you’ll do next.

Create a Product

You’re feeling good about the money you’re earning from this new side hustle of yours. But in order to truly give up the grind, you have to put your “income on autopilot,” a la Tim Ferriss. The process is simple, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

The good news is you’ve got all the lecture material from PowerPoint and Camtasia. In other words, you’ve got the “why” on your subject matter. The bad news is you’re missing the “how” with your product. People will buy the “why,” but they’ll form a line around the block for the “how.”

Either with your phone and a tripod, you will need to film the “how.” In other words, you need to have video evidence capturing that you not only know what to say, but how to coach your skillset as well. Don’t hold back on this part. Coaches love adding exercises to their database and will search high and low for cues they’ve never heard before. This will be the backbone of your product. Make sure it’s got plenty of meat on it.

They know the why. You’ve taught them the how. Now your buyers need a filter. Basically what this means is they want you to show them how to take what you’ve given them and apply it to their specific situation. They want to create their system, not duplicate yours. They want autonomy. Provide them with anecdotal evidence you’ve found in certain situations, examples including (but not limited to):

- How to apply this with youth athletes

- How to apply this with time constraints

- How to apply this with a small gym space

- How to apply this with bad weather

- Team setting considerations

- Private sector considerations

After you’ve created the product, the process goes quickly. Find someone who’s good with ClickFunnels or Infusionsoft to “house” your product, and then craft a lead-generating PDF to grow your email list. (I’m a fan of ConvertKit, personally.) This will allow you access to your potential customer’s inbox, so you can build that relationship and move them closer to the point of purchase when you’re ready to launch your new product.

Now, before my inbox overflows with contrarians, let’s discuss this strategy.

1. This strategy is meant to expedite, not overnight, your grind.

The problem with only being one chapter ahead of those you’re educating is you could be reading the wrong book. In other words, there are a lot of “experts” on social media who are anything but. They’ve been reading the wrong books for way too long. Hell, they’ve been in a different library altogether. Don’t be those folks.

You actually need to have some depth and experience with the subject matter. I hired Derek Hansen as my coach so I could literally immerse myself in sprinting. Yes, it gave me knowledge. Yes, I practiced what I preached. But what it did for me above all else is grant me empathy. “Knowing what it feels like…” is a secret weapon if you’re to be seen as an expert.

Remember: expedite, not overnight. I don’t know about you, but I’d take 18 months to grind if it meant my freedom got expedited by several years.

I don’t know about you, but I’d take 18 months to grind if it meant my freedom got expedited by several years, says @huntercharneski. Share on X2. “This ain’t a diss song.”

It isn’t my intention to bash the industry’s greats who have been here long before most of us. It is only my intention to show that your path isn’t binary. The message preached about grinding for passion and pennies doesn’t sit well with me. Nor does the assumption, “If you aren’t willing to do so, then you’re in the wrong industry.” There is another way. This is another way.

Ironically, it was a member of the “old guard” who pushed me to become an expert on speed and take the leap into my new life: Jorge Carvajal. Jorge, I apologize for calling you old, my friend, but you’re a guy who’s been around for 30 years who too few know about!

3. Money isn’t everything.

At this point you might be thinking, “Dude’s a sellout,” and while you’re entitled to your opinion, I strongly disagree. If you think this article is purely about making more money, then you’ve missed the point. This is not an article about accumulation, but rather a shift in paradigm. In a word, freedom.

Was money important for me to extricate myself from Michigan and move to Arizona? Absolutely. Did it take a lot less money than you might think? You bet. Money can be a vehicle to drive you toward your dreams, no doubt. But it isn’t everything. John D. Rockefeller, who had more money than any of us ever will, once said, “A man’s wealth must be determined by relation of his desires and expenditures to his income. If he feels rich on $10 and has everything he desires, he really is rich.” Having a “rich” life is easier to obtain than you think.

What If I Still Want to Coach?

I think it is safe to assume the majority of us got into this industry because we love coaching. If you’re like me, your affinity for kids is what lights a fire inside your coaching heart. This is why I am not advocating you give up coaching all together. I am hoping you will give up the grind of it, though. Allow me to explain.

When I still owned and operated my facility in Michigan, there was one class per day I lived for: the 5 p.m. middle school group. It was at the perfect time of day, for starters. I’m a lark, and so my cognitive functioning peak is in the morning. This allowed me to work on the business between 7 and 9 a.m. Then came self-care (something else the industry seems to frown upon, but that’s for another article), which for me was sprinting. After I ate lunch, it was about 1 or 2 in the afternoon. I would take a nap, so I was charged and refreshed for the 20 or more rugrats who’d come barreling into the gym.

Anytime this didn’t happen was no one’s fault but my own. I would try to cram more work into the afternoon and/or early evening. Or worse, I would push aside the vital few tasks in favor of the trivial many. This might upset some, but those less important tasks usually were coaching all the classes. As the business owner, I was under the delusion that wearing every hat was possible, and even worse, worth it. In either case, this affected my love for both the business and coaching, which resulted in the middle schoolers not getting the best of me, but the rest of me when 5 p.m. rolled around.

So I was stuck. I loved coaching. But I also knew as the business owner (and now writer and marketing consultant) coaching every group was not a good use of my time. In fact, it cost me money. Before leaving for Arizona, I put systems in place so I could grow the business as well as coach the kiddos in the evening more often than not. Fast forward to life in Phoenix—my daily schedule looks almost identical. If I have clients in the evening, I train them. Or if it’s track season, off to Pinnacle High School I go.

My point is this: A coach’s life can be stressful., but it doesn’t have to be. You shouldn’t have to choose between coaching and owning a business. It’s just plain wrong to expect yourself to do everything if you’re in the private sector or in small team settings. You ought to have the freedom to pursue opportunities while still being a coach. You can have it all.

Getting Started

How will you be seen as a “go-to” coach as 2021 looms closer by the day? Kettlebell maestro? The plyo guy? Deadlift Debra? The possibilities are endless. My advice? It is easier to fill a need than create one.

- Ask yourself what subject matter you understand—and can teach—better than most.

- Once determined, announce your free master class, take questions, and convert FAQs into modules for your course.

- Anyone who asks a question gets admitted. Create a private Facebook group, and you’re ready to go come 2021.

- Change your FREE class into a paid one.

- Repackage your class into a product and put income on autopilot.

I look forward to watching you give up the grind and take the leap into the next chapter of your life. Or perhaps you’re more comfortable in the passenger’s seat, staring out the window as life passes you by? It’s your choice.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF