Hidden away in some strength and conditioning corners is massive hype about the close grip snatch, an option that is so inflated, it’s frightening. There are certain times a narrow grip is a good alternative to the traditional width, but the promise is overblown. In this article, we intend to debunk this problem before it continues to grow.

Bad logic and poor reasoning don’t stop with the snatch exercise, they extend to other exercises, making this a perfect learning experience.

Even if you don’t use the exercise or don’t plan to incorporate it into your program, narrow grip snatches are a perfect cautionary tale of bad sport science meeting bro science. If you don’t think it’s worth talking about or investing a few minutes, the problem, pardon the pun, is wider than you think.

The Close Grip Hype is Still Alive

We’d assumed the narrow grip would eventually fade away–there’s been just enough hype around it to be annoying. Instead, the trend is growing and needs to be squashed. The option to use a close grip is just that, an option, not a necessity. Using a traditional grip, in fact, has more value. The hype comes from three popular arguments: Going narrow will reduce injuries (unfounded), improve impulse (foolish idea), and better teach the lift (a stretch).

For every 100 strength coaches, we’ll see about a dozen using a close grip snatch believing that it helps training. And we see some veteran coaches going narrow for reasons that make no sense at all. It seems no one cares about this issue because the strength and conditioning profession has bigger fish to fry with all of the injuries and drama it’s experiencing at elite and youth levels.

- A close grip is not safer to the shoulder joint

- A close grip does not provide athletes with any power benefits

- A close grip will not fix technique errors magically

If you have a good reason to use a narrow grip, we’re not going to ask you to change. If you’re using it due to outside influence, it’s time to ask why. A grip change of just one hand span can improve or ruin an athlete, and promoting the wrong grip is negligent.

Does The Snatch Grip Width Matter in Sports Performance?

Any time we discuss Olympic lifting, there’s a debate between what is good for the sport of weightlifting and what is good for sports. This subject has been beaten to death, and the arguments do not encourage changes that make a difference in training. This article is not meant to convince those who don’t use the lift to convert to weightlifting movements; it will help those who coach lifts in the weight room who have similar needs. When we make an exercise selection, the details sometimes matter. If a coach decides to snatch, does the choice of grip choice make a difference in the end?

A simple way to envision grip for a barbell snatch is to picture a continuum starting with the hands as wide as possible, so they’re flush with the plate, and becoming less wide, so they’re shoulder-width straight up. A clean or close grip is not narrow; it’s just narrower than a conventional grip. The grip used isn’t related to competition rules, it’s about finding the best mechanics to do the lift safely and effectively. Grip terminology will be different and sometimes contradictory, so it’s better to look at the actual spacing rather than the name of the grip.

Technique matters regardless of what you do to prepare for sport. Whenever a coach chirps that it’s not worth time to learn, always remember that they’re missing the point of Olympic exercises. A good teacher and a good athlete can get started in sessions, and some wise coaches teach the lift without even touching a barbell. The snatch is easier to teach because the catch requires less flexibility and feels more natural to many athletes. Grip choice is important for five reasons:

- Hand Strength–Although hook grips and hand strength development are not easily connected, the grip width will influence the demand on the hands. Rarely does an athlete have an issue gripping the bar unless they simply avoid the weight room.

- Shoulder Mobility and Wrist Health–A wider grip adds lateral strain to the wrist but decreases mobility demands on the shoulder. The bar also factors into width–even a large athlete is usually constrained to the standard length.

- Athlete Body Structure–The body’s anthropometrics govern the adjustments made to many lifting movements. In the snatch, some athletes need to go wider than usual but rarely do athletes need to go narrow.

- Exercise Mode–Pulling from the floor, the blocks, and the hang position are all unique. Snatching at different heights may encourage changes to grips for some lifters and relates to the structure of the athlete and rate of force generation.

- Leg Drive and Hip Contact–Traditional (wide) grip sets the bar exactly in the crease of the hip. The placement makes the “bump/scoop” most effective when elevating the bar because effective snatching uses a lot of leg drive. When using the narrow grip, the arms extend longer and the bar contacts the legs too early, shortening the leg drive. Note: If you hold the bar in the correct position, you should be able to lift the leg into hip flexion without moving the bar to help you do so.

As you can see from these five points, the grip matters regardless of whether you’re doing recreational lifting, training for a weightlifting competition, or training for sport. All athletes doing the snatch must pay attention to the details and not fall into the trap of looking at everything outside their sport as secondary. In fact, athletes get injured or fail to improve because they look at general training as second-class and, therefore, the lifts don’t develop.

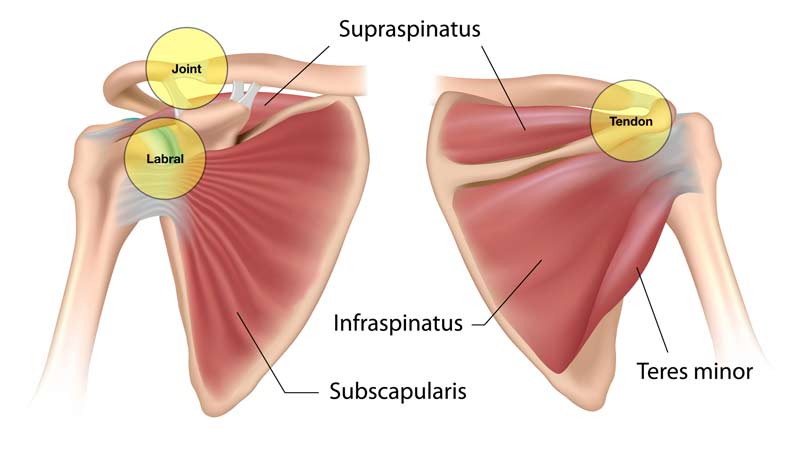

Can a Shoulder-Width Grip Protect the Shoulder?

Now we’re going to get controversial. Going narrow will not improve safety. It makes the load lighter which leads to the belief that the movement will be better on the joint. Sounds fine on paper, but the problem is that load and mechanical strain juggle between physics and anatomy, and the theory doesn’t hold water. Anatomical safety when things go right is one thing. But if the grip encourages compensations and increases risk, it creates a bigger problem. If overhead snatching is so dangerous, why play with fire at all and instead do clean pulls?

Although the snatch is received overhead, it’s not the same exercise as an overhead press. It’s like a handstand on your feet, with the reception of the load going through the upper body and down to the ground. The difference is that walking on your hands has a different set of risks than lifting, including starting and finishing.

A more narrow grip adds more compromise if the weight moves backward, which happens with neophytes and beginners. A simple example is this: When we were in youth sports warming up, we stood up and held our arms out wide and made circles; try doing this with your arms straight above. Can’t do it.

Instead of trying to impress you with anatomy lessons, we’ll give you points that are logical and evidence-based. There are a few times when the research and experience don’t jive well because much of the research on shoulder health is population specific. This doesn’t help a very small group of athletes who chose different grips with one exercise.

One example is posture. Specifically, overhead lifting and kyphosis and how an athlete moves their upper limbs and lifts loads. If someone is severely restricted and their hands can’t go above their head (so they can’t keep them perpendicular to the ground), posture becomes a real problem in this position.

Some elite Olympic lifters can’t perform an overhead squat well and still compete at a high level when a loaded barbell is above them. Going narrow has no known health advantage, and going wider has no risk. Extreme positions are not true arguments; going wider than shoulder width, say two hand spans, isn’t extreme by any means.

Because some athletes are not good candidates for overhead training, going narrow become wishful thinking even if it were advantageous. If an athlete has an orthopedic restriction, going narrower is usually harder–not easier. Perhaps an extreme minority of athletes will benefit from a narrow grip, but most will feel more comfortable with the wide grip’s less demanding range of motion.

Some coaches have gone outside their scope of practice and focused on corrective exercises as a means to prepare for overhead pressing after performing assessments looted from the physical therapy profession. It’s not a faulty idea, and we believe in orthopedic evaluation, but it’s better to refer out to someone more qualified than to put on the therapy hat and move out of your lane.

Will a Close Grip Create More Impulse?

The next time someone claims a narrow grip improves the impulse of the lift, ask them to write the formula out. Nothing shuts up a coach more than asking them to prove their bogus high school physics with a request to see the numbers. And since every performance gym has whiteboard or chalkboard, “impulse” coaches can’t escape. Coaches don’t need to write out a formula like in Good Will Hunting or A Beautiful Mind, but they need to defend their claim with science.

Look at squatting and jumping. Anyone can squat slowly, but nobody can jump slowly unless they’re in an environment that’s close to zero gravity. Squatting the resistance during the lift stays the same as one goes up, and the mechanical leverage demand becomes easier at the top. Jumping and propulsive forces need to be high and early to get the body to project and overcome gravity.

Applying force longer rarely helps sport unless the result is faster or farther; narrow snatches mostly lengthen the force application. Strength coaches want more force or power, not longer barbell displacement. Squat depth, for example, has very specific benefits at different joint angles which is why accommodating resistance is popular in some circles. Jumping with the bar is a convenient cue, but the intent and what actually occurs must relate to what the athlete has the ability to do rather than what they want to do.

Propulsive forces overcome inertia and outside forces to transmit energy toward the right direction. Thrust is about force. It’s about having force applied fast and early. Many tall athletes can cheat a light load to achieve better bar speeds. But they also betray their development because leg power is about speed at the right time with the right motion. Having speed past the chest line is only interesting if it comes up from the legs, not from upper body motions that seldom transfer outside of narrow grip snatch contests.

Longer barbell stroke might increase the total work performed, but that’s just a mirage of a metric. It’s hardly valuable outside of burning more calories in a group exercise program. Wider grips force the athlete to get the job done faster and earlier, a fashion that transfers better and creates a safe position if they decide to catch it above their head.

Wider grips force the athlete to get the job done faster & earlier, transfers better & more safely, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XWithout getting into unnecessary math calculations, the idea that a longer barbell stroke leads to more impulse is a misguided fallacy. Generating force for sports performance, specifically propulsive force, requires fast work rates, not adding distance to a movement. It’s not about the total distance the bar travels; it’s about how force is transmitted during a high enough time period to matter when the unloaded body is on the field.

When training the snatch, coaches must note the saying, “when the legs are done extending, the upper body is just pretending.” They should focus on what the legs are doing with the bar instead of a longer displacement with the finish. In weight training, it’s easy to fix on the iron bar. Look at the body first–it’s too easy to look at the barbell path instead of the relationship between both.

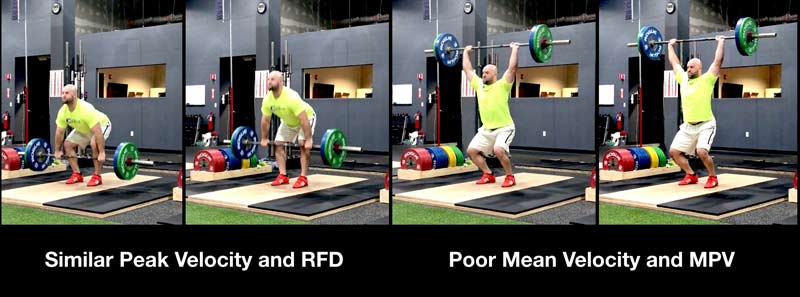

Impulse is a great buzzword, but it’s important to focus on more accessible concepts. While VBT has had a lot of innovation and advancement, there are times when a bad idea is made more seductive with technology and sport science.

Problems with Going Too Narrow

Going too wide risks straining the wrist over time and makes the exercise more demanding when pulling from the floor. What can go wrong with a narrow grip? Most of the users, nearly all in sports training, go narrow and finish high in a power position. As the bar gets further away from the ground, the load prescription usually decreases, and rightfully so. If you want to finish high, your upper body must contribute to complete the lift.

The “elbow bends, power ends” mantra is correct; when the athlete transitions from extension to receiving the bar, the propulsive forces stop. Going longer could cause you to lose tension early and cut the pull early when snatching from the floor.

Some people also miss the point about the proximity of the bar near the top of the second pull/start of the third pull. Narrow grip almost always pushes the bar too far forward when turning it over. An experienced lifter may get away with this, but most people will try to muscle it up because of the lack of leverage. Usually in the area from the chest to the head, you will see the bar much farther away from the body for those with long arms.

If you have long arms or if you go too narrow, snatching from blocks or a hang position also compromises the movement because the catch now has to manage a load that might not have the height necessary to catch safely. We see this with athletes who are taller who don’t have the hip and ankle mobility to catch low; they usually chase the bar forward to catch safely.

Adding more height demand for a tall athlete makes the process worse. Tall athletes may have reactive and RFD qualities that create a great pop from the starting point, especially from above the knee, but sometimes they need time to gather speed and have better peak velocities on their lifts. Catching high and slow is not smart if you want effective VBT training or if you just want to perform the exercise correctly.

If you’re going to use a clean grip, then just clean pull and forget the catch entirely. We’re not against catching the bar; we care about pulling properly and avoiding problems. If someone is so worried about catching that they think hand spacing will create a major difference when going narrow, they should just avoid the problem altogether. Some coaches like the snatch and don’t find the catch as a point for discussion. Going wider from a hang, blocks, or the floor changes the lift dramatically, and we reduce the load to accommodate the mechanical changes.

Going lighter on the clean to reach higher bar speeds that are similar to the snatch may sound fine. But the load on the body is different–even if the velocities are the same for the peak and average. Also, pulling styles and starting points can dramatically change the purpose of the lift from generating explosive strength.

From a pulling perspective, narrow grip has little value–the snatch becomes too close to a clean, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XFrom a pulling perspective, a narrow grip has very little value because the exercise is too close to a clean. Likewise, going lighter has little value because the catch creates a constraint. Going narrow to avoid shoulder injuries can backfire. Before taking the leap of faith that narrow is safer or more effective, decide what your goal is for the snatch as opposed to a clean.

How Wide Should You Go?

It’s important to have a tight process that quickly connects the transfer of the load from the feet through the body explosively. Most coaches who instruct the snatch understand that the hip crease marks where the bar should be in a standing position during the snatch. While coaches quickly gravitate to arm length, it’s the relationship with the entire body that’s important. It’s frustrating when random formulas are used that connect arm span and grip width to determine where to hold the bar without any consideration of the rest of the body.

Sometimes athletes go “super wide” during warm-ups to drive the pelvis to finish and to snap quickly with drills. Before adding this to a program, consider whether your athlete has a tight bicep or is unfamiliar with the exercise. Some coaches also space the grip incrementally to keep a busy mind focused when training becomes monotonous. If the grip is not perfect, don’t emphasize that all hope is lost. Keep the grip wide enough to allow for freedom of movement and completion of the exercise. Just as a triple extension in sprinting is a generalization and not a true event, so is peak output with Olympic lifts and maximal bar displacement.

The deeper the catch, the more important the technique used to receive the bar. Most athletes don’t perform the full lift and choose to use a shallow catch, also known as a power version. It’s not clear why a decrease in depth equates to the use of the term power–the power snatch and power clean assume the reception of the bar is closer to standing than squatting.

A taller reception of the bar creates a higher demand on an already compromised catching scenario for athletes. Going wider speeds up the process, leaving the rest of the time available to prepare for the catch. While having a longer time for pulling seems like an easier task, narrow grips make the catch slower and often incomplete. This forces an athlete to adjust to catch the bar instead of placing the bar in a more favorable location. Wider does the trick provided there’s full leg extension. Some changes in width may help unique circumstances, but as long as the lift is comfortable and balanced, athletes will be fine.

Use the Grip that Makes Sense for You

We are not bashing the use of a narrow bar grip. We’re saying the choice to use a fairly typical grip that is wider than the shoulders is not wrong. A good execution of the snatch lift will be seamless and extremely effective, and coaches have used the wider grip for years without problems. Unfortunately the mind can get lost in ego for coaches wanting to be too cute or creative to settle for the tried and true, and this experiment becomes a bad road.

Make choices based on real benefits, and do you your homework on why you went down your chosen path. We’ve gone wider and narrower for specific needs, but only when we had enough ammunition to fight for those changes.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Just read your article about the close-grip snatch. You don’t like them, fine. However, I’ve found that doing a few light sets as a warm-up before regular snatches appears to help athletes get under the bar faster. Also, in the past when they were a world power in the sport, elite Bulgarian weightlifters would often do jerk-grip overhead squats with weights equal to their regular snatches.

Thank you,

Kim Goss, MS, CSCS