[mashshare]

By Graham Eaton

If coaching is equal parts art and science, then working well with other coaches on the staff is crucial. Coaches who are flexible with each other will make their team better. This can promote athlete buy-in because of the visible connections and communication between all coaches.

There is a dizzying array of choices when it comes to exercises and programming. I have ideas about what is necessary, and so do our jumps and weight room coaches. It is up to us to communicate often and compromise as needed to keep the athletes healthy and happy. I really feel that our goal is their performance, not pushing our own agenda. We need to keep our egos in check.

First off, I don’t think it is my job as a high school coach to reinvent the wheel or make my mark by devising cutting-edge exercises and training methodology. I think the good stuff is already out there. It is my job to sift through things and implement them in ways that make sense. Sometimes it can feel like I have to be a “Jack of all trades, master of none” type figure. Thankfully, I have a great team of coaches to help me.

If coaching is equal parts art and science, then working well with other coaches on the staff is crucial. Coaches who are flexible with each other will make their team better, says @grahamsprints. Share on XThere is always something new and exciting in coaching and you should approach it with a mix of curiosity, openness, and skepticism. When coaches see a new concept, new information, or new exercise on social media, they often have strong emotions, whether positive or negative. You can either embrace it fully or be threatened by it and ultimately reject it.

When listening to podcasts, reading articles, or attending clinics, I sometimes come across a really cool idea and concept and, quite frankly, I don’t know what to do with it. If it isn’t something I am all-in on, then I just won’t use it. This doesn’t mean that I regret having encountered the information or that after some ruminating it won’t become useful. Sometimes, another coach’s situation just doesn’t pertain to me and mine doesn’t pertain to them.

Chances are that you and your team of coaches are already doing some things really well. Also, like our team, you may perceive shortcomings that you need to address. Change is necessary for growth. It also isn’t good if your program constantly goes through massive overhauls every year because you feel the pull of the latest trends. Both instability and stagnation can be harmful to a program.

At some point, you and the other coaches need to adhere to a set of training mantras or principles that you believe in and just get better at those with a nearly imperceptible rate of change. If you teach the key concepts and foundations on the track and runway and in the weight room, then everything else is just logistics with some chaos sprinkled in to motivate. I am very lucky to work closely with two coaches who have clear goals and beliefs.

Something for Everyone

At Triton, we prioritize speed because we had a drought of speed and decided to address this. Once speed is present, it becomes easier to train the other energy systems. Track isn’t just running fly 10s. The track events are a harmonious blend of the ATP, lactate, and aerobic systems. Race modeling and aerobic work are important, but having lungs and a plan is no good without some wheels. Trust me, with our population, I am willing to let some things take a back seat.

If speed is 1A, then movement is 1B. I try to utilize warm-ups that get all athletes ready for all their coaches. I don’t think most high school athletes have an abundance of experience with motor skills. Recesses are shorter, gym classes are becoming less frequent, and video games are all-encompassing. Jeremy Frisch has inspired me with his balance of structure, play, and experimenting. Early in the season, we spend a lot of time using warm-ups to assess abilities and readiness. I think if you coach a large group, you have to calibrate to a certain level what defines a typical athlete in your program.

I do not usually come with an exact plan for warm-ups. I know coaches reading this might raise an eyebrow or cringe at this. I have been asked for an exact list of my warm-up “drills” before, and I am usually not sure how to respond. I am not a Type A coach, with templates and lists of every warm-up task I am going to do in every cycle of training. I enjoy thinking on my feet and I find that if I am overly structured, I limit opportunities and creativity both in myself and my athletes. Track is very linear, obsessive-compulsive, and rehearsed when compared to other sports. A block start is practiced over and over, whereas one play in football can have several different options.

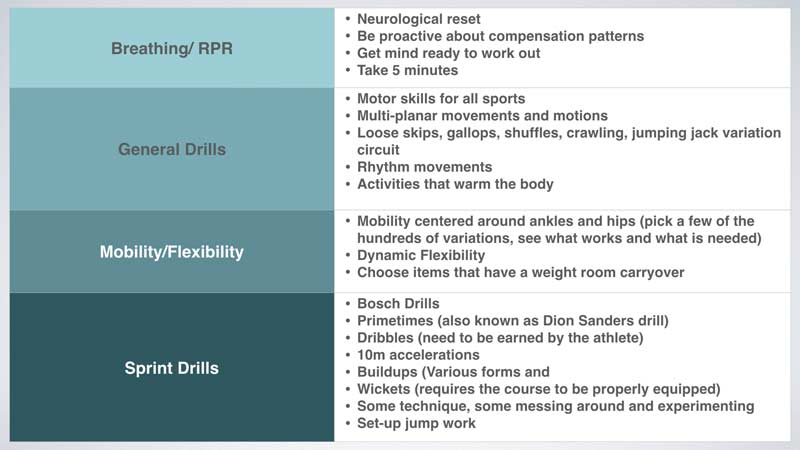

I do have a rough outline, as well as a purpose for why I do these things. My rationale might not match up with another coach in a different situation. I do a few of each and repeat, progress, and regress as needed.

This is enough of a plan for me to prevent me from becoming unhinged. I want my athletes to become more complete athletes and they need variety to accomplish this.

The starting point for most of our drills is Dr. Ken Clark’s three-bucket position. Imagine a bucket of water on your head, thigh, and toe, and it elicits a pretty good starting point posturally. I like this isometric because it develops hip flexor strength and also provides a reference point for later items like dribbles and wickets.

Frans Bosch has been a huge influence on our movement and sprint drills. Basically, the thought here is that, across our sport or in most sports, there are very few basic patterns (attractors). Although individual athletes may express power and speed with different styles, we expect the attractors to be very similar. By adding chaos and fluctuations, athletes can adapt and become more resilient. This resilience can make the attractors more deep-rooted. You do need repetition and practice to get better, but monotony can hinder learning and progress. No struggle, no progress.

You do need repetition and practice to get better, but monotony can hinder learning and progress. No struggle, no progress, says @grahamsprints. Share on XCommonalities between all of these are:

- Rhythm/timing

- Minimal energy leaks

- Neutral hips

- Relaxed head/neck

- Stiff lower limbs

- Scissoring or switching (hip flexion/extension)

- Arms that contribute to timing or vertical pulse (do drill without arms, add them back in)

I don’t really give too many specifics on what athletes should to do with their arms. I would rather allow them to self-organize with subtle cues like “no tension in hands/wrist,” “turn the swag on,” or “up and down with a bop” if something looks rigid or, for lack of a better word, “off.” A lot of this is a potentially moot point because without good lower limb stiffness/adequate time to reposition limbs, the timing and posture cannot be present. So, arms aren’t really a big rock at first with our athletes, but I put them in positions to feel the contributions.

If they become good at a drill, I simply reorganize and change the task. This can be both motivating and frustrating in a good way. Block starts are frustrating. Hurdles are frustrating. So, I like some unpredictability in our practices.

I think if you change the task, you will change the athlete and their resilience. Late in the season, when we are looking to be at our best, I often do away with a lot of these if I feel the athletes have progressed adequately. I also let them choose things that they like and try to invent something new. You would be surprised how motivating even the littlest of choices can be.

Video 1. Different or the same? New tasks with a similar purpose can keep boredom at bay. Flexion and extension drills with good timing in different rhythms are a great way to challenge the athlete to acquire skills.

The Weight Room

We lift 2-3 days a week. Our shotput and discus coach, Katelin Invernizzi, is also our weight room coach. She is a former distance runner who has competed in figure shows, powerlifted, weightlifted, and done CrossFit. These days, she tends toward powerbuilding for herself, but it is clear that her influences span across several of these disciplines. She spends a lot of time addressing specific mobility and technique issues here. She also gives me suggestions for items to include in my warm-up that can make the time in the weight room more productive.

If she feels someone is better off doing a dumbbell split squat than a front or back squat, we meet them where they are at. We also feel that the athlete who can do both bilateral and unilateral squat variations will probably benefit from this extra repertoire. We used to be big pushers of bilateral squatting only, but have come around on unilateral mostly because of the reality of a 12-week season. It often takes five weeks just to get athletes to a point where we feel comfortable having them front squat with even a partial range of motion. Katelin would rather a kid have at least a point of entry to begin the process. It is motivating and easier to progress with a bevy of squat modalities, but we can’t afford to overthink with athletes with low training ages.

The programming isn’t super fancy and many kids don’t lift. Most of our two-season kids are invited to the weight room. For most others, there is no continuity and we feel like we restart every spring season. It may sound like a cop-out, but if they don’t lift during soccer and basketball season, then lifting for 10 weeks just adds fatigue.

I tell her that I need my athletes to just get stronger and become more durable. We joke around about giving the kids “wowies,” which are just the usual things in a more exciting disguise. The only thing I communicate is selecting exercises that are a continuation of the day’s track work. This is a generic form of undulating periodization.

We also don’t plan deload weeks. School vacations, doctor’s appointments, tests, driver’s ed classes, and all sorts of other things eat up their time. I am not sure if this is just the culture of our school district or also the reality elsewhere. Either way, it is pretty frustrating, so we generally just train and do a little less lifting in a tough stretch of competition, but we never do nothing.

A few rules or guidelines we follow are:

-

- Don’t have your athletes do lifts that you don’t know how to do. If you don’t know how to teach your athletes how to squat, clean, or deadlift, then don’t. I don’t think they are that hard to learn, but there is more to them than “sit back,” “jump and catch,” and “pick the bar up with your legs.” Poor t-spine mobility and an absence of a front rack mean a no-go on front squats and cleaning.

-

- Do main lifts for strength on speed days, as well as med throws and plyometrics. We do teach the clean, although we are debating whether to keep it. It does have value for helping our athletes become athletic and receptive to cues.

-

- Do hypertrophy reps on one lactate day to add some tendon/muscle strength without frying the CNS or as assistance lifts to support main lifts.

-

- We don’t do triphasic lifting or post activation potentiation. These are not advanced lifters and they already have enough to recover from. Too many things lumped together creates crappy form. Focus on one thing at a time or the main thing.

-

- Bar speed doesn’t matter if athletes are not strong first. Strength comes before power. We don’t have measured VBT technology like collegiate or professional organizations. Toward the middle/end of the season, we may ask specific athletes to move the bar with more intent. They should always execute the eccentric with control, which will set up a better concentric.

- Increasing force generation though lifting doesn’t guarantee that force application increases. Get stronger, but don’t let the lifting volume ruin the sprinting!

Fitting in Jumps and Hurdles

I feel that a strength for us is not overworking our athletes. The jumps coach, Tyler Colbert, and I communicate before and after every single practice to make sure that we both got in 80% of what we needed. It will never be 100%. He just finished his first year and did a terrific job with a mostly underclassmen jumps crew. He attended clinics and watched countless videos. I think he understands that coaching is about continual education.

He is responsible for the jumpers by himself. The only thing I ask him to keep in mind is that all of them are sprinters first and our cues need to be consistent. Tyler often assists me with the sprints workouts and devises a workout appropriate for the JV runners.

Here is what we have generally agreed on for our week’s plan.

-

- Long and triple jumps are accelerations. It is important that athletes learn how to set up a good jump by building to a good rhythm to stay running. Spinning the wheels does not yield a good jump. Do full approaches on acceleration/max velocity days, but allow them to get some Freelap timing and acceleration work in. I think 50% of the main workout is a fair percentage and can make the jump work better.

-

- The high jump and pole vault are paired together as vertical jumps and can be done on X-factor day and before a lactate day.

-

- Make sure each jumping event has two practice days in addition to the meet day—one full approach and one with something else.

-

- If there are two meets that week, do one decent session and then use pre-meet time to get steps. Cut out the fluff and get specific.

-

- Ask each other: Is something lacking or missing? If so, can I address it in warm-ups?

- Ask Tyler: Don’t do any extra plyometrics other than what are included in the sprint complexes on those days. Is there a plyometric/jump you would want me to program that you think has value?

For year one of us working together, we did a solid job. I want him to speak up. If a jumper is struggling but doing well on the track, then perhaps he should skip the main session altogether. It becomes a little fuzzy when you have an athlete who sprints, hurdles, and jumps.

This year, we had a sophomore boy do pretty well in the 400 hurdles, but I don’t think he hurdled more than five times in practice. His technique is not great, but speed, 400-meter work, and jumping work were a priority. Something had to give. Next year, we may look back on it and say, “Why were we doing that?”

Everyone thinks they do things the best way until the future reveals otherwise. I guess time will tell, but we try not to be married to anything. If something works better, we are sure to work through it in time.

I have such a reductionist approach to hurdles because our athletes are sprinters first. This year, we did not have a ton of success due to a lack of speed and experience. This will get better and I need to get better at selecting athletes suited to hurdle. I think if an athlete is fast enough or tall enough, can use their trail leg effectively, can execute a handful of dynamic drills with good arm and leg timing, and can hit hurdle one well, then they will eventually have success. I cannot make a kid who runs 13.0 in the 100m into a great hurdler, yet. I think we are set up better here for the future.

Changes Ahead

We had a solid year this past year, but we need to continually adapt and refine. After attending the Juggernaut Training powerlifting clinic a few weeks ago, I started thinking heavily about minimum effective volume (MEV) and maximum recoverable volume (MRV) and what this means for the sprinters at Triton. On the surface, a track coach may question the value of anything powerlifting-related because our athletes are not powerlifters.

I think it’s important to strive to hit the balance between minimum effective volume and maximum recoverable volume in any speed, strength, or power sport, says @grahamsprints. Share on XI think in any speed, strength, or power sport, that striving to hit the balance between MEV and MRV is very important. How do we elicit a continued response to training without overdoing it? You can’t just do next to nothing any more than you can go hard every day.

Some factors that help determine these volumes are:

Gender

Females can do more volume. They have less muscle mass, so therefore there is less muscle to be damaged. The presenter at the clinic noted that females can do five sets more per week than males. What does this potentially mean for our female sprinters?

-

- Slightly longer intervals. This could mean running the 27-second drill instead of 23 or 20, or running 300s instead of 200s.

-

- They can handle slightly more absolute speed as long as the Freelap timer agrees and doesn’t show a huge drop-off.

-

- More aerobic work for long sprinters since they run longer than their male counterparts.

- In the past, I have trained females slightly differently, but feel I went too far away from that this year, as my 4x400m relay underperformed. I also shifted some girls around, so where they may have done 400 and 4x400m twice a week in the past, they did 100m/200m or 100m/400m. We have a month-long stretch of two meets a week that makes it tough to do anything crazy. That 400/4x400m double is very important in this stretch.

Lifestyle

Unfortunately, it’s very hard to control this one. All we can do is educate and then respond to what we see. I do try to alternate training weeks so that every third week has less volume while maintaining appropriate intensity.

-

- Diet, sleep, stress

-

- The body can’t distinguish between the stress of a test and the stress of a squat or sprint.

- I am working through a simplified rating system to implement next year. If someone rates their fatigue or perceived effort as higher than expected, I will investigate and adjust if needed. I can’t give more information here because I don’t know what this looks like yet.

Genetics/Speed

Just like insanely strong powerlifters who squat 900 pounds, more explosive athletes will need less volume due to how taxing their maximal work is. If you have a kid who runs a 10-meter fly in 1.30 seconds, he will be able to do that more often than your genetically gifted athlete who runs a sub 1.00. This is why Tony Holler’s Feed the Cats program has been so popular.

However, if you want the kid who runs 1.30 to improve, he will probably need some more repetitions to get better. He isn’t a cat yet. For my fastest kids, I find running personal bests is the hardest thing to recover from. An active nervous system will have more fatigue after going at “psycho mode.” Watch for an athlete slowly getting sorer or dropping off timewise, and rest them before it is too late.

The bottom line is that, as a high school coach, you’re probably better off doing a little less than doing more, unless something isn’t panning out. Then, you may need to do more. Share on XThe bottom line is that, as a high school coach, you are probably better off doing a little less than doing more, unless something isn’t panning out. Then, you may need to do more. Look at athletes’ practice times and meet times. If something isn’t matching up with expected performances, then investigate a bit more.

Working Together

In order to keep your athletes happy and healthy, you need to perfect the art of cross-coaching. Find time to discuss training and belief systems with your team of coaches and know what they are doing. Every coach on your staff plays an important role and can make major contributions.

I am very thankful to have Katelin and Tyler in my corner. We are three coaches with varied backgrounds who can come together for the express purpose of making our athletes better. Both of them understand the factors that influence training and continue to educate themselves, which in turn motivates me. I think pushing your staff in this manner ensures that no one ever settles.

Katelin and Tyler are both former distance runners who have run fly 10s this summer. This was without prompting. Both of them noted how sore they were the next day. I appreciate this exploration and find it important because you have to understand how different training affects your athletes. Coaches often have preferences in training. Katelin lifts, Tyler runs marathons, and I like to chase the pump and do drills. At the end of the day, we know that our inclinations take a back seat to what the science of sprinting suggests we do. Just because we trained or like to train a certain way doesn’t mean we should do that with our kids.

Coaches’ inclinations take a back seat to what the science of sprinting suggests we do. Just because we trained or like to train a certain way doesn’t mean we should do that with our kids. Share on XTyler has made it his goal to bring more short speed work over 90% into the season with cross country runners, who he coaches as an assistant coach alongside his father, Joe Colbert. Joe has always done a great job of reminding us that the kids are “our athletes.” It is not uncommon to find a mid-distance runner in the sprint group running our 5x200m staple workout. I have also sent 600m runners out for tempo runs before with him. There is something to be gained from everything.

The shared responsibility can turn a good team into a great team. We are excited to move forward. Check your egos, balance the training, and make sure every coach has a voice. Start planning now.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]