When you make a living in the sports performance industry, whether it’s working for a professional team or university or providing a service to a group of individual athletes, you’re in the business of making promises. These promises can be accompanied by a set of strategic recommendations, injury prevention strategies, recovery enhancements, technological improvements, or psychological interventions. The “promisers” typically have their own lane or niche. Some skill sets are easy to identify, while others are often steeped in intrigue, mystique, and complexity (i.e., “He’s using lots of big, multi-syllable words that confuse me, so he must be an expert!”).

In my case, I’m often called upon to improve the speed of individuals and teams. Organizations know what they want. The “product” can be very measurable. And, although unspoken, this product must lead to wins and championships—no questions asked. Making a team faster with no improvement in the “Wins” column is not acceptable in the land of billion-dollar pro sports organizations. Being able to deliver on such promises is quite another proposition, and living on this razor’s edge can be quite a stressful existence. So, where do you begin?

It’s often thought that producing speedy athletes involves a special combination of well-packaged exercises and drills dispensed by animated coaches. When it comes to making an entire roster of players faster, some assume that you simply dispense more drills and exercises in a one-size-fits-all manner, preferably with loud music blaring in the background. And expensive cutting-edge technologies absolutely must be part of the package to demonstrate the efficacy of the exercises and drills, avoiding relegation to the label of old-school coaching dinosaur. While trendy exercise programming bundled with sexy tech is thought to yield rapid and sustainable results, I must bring you back to down to earth and set the record straight. Most of the bottom dwellers excel at this approach.

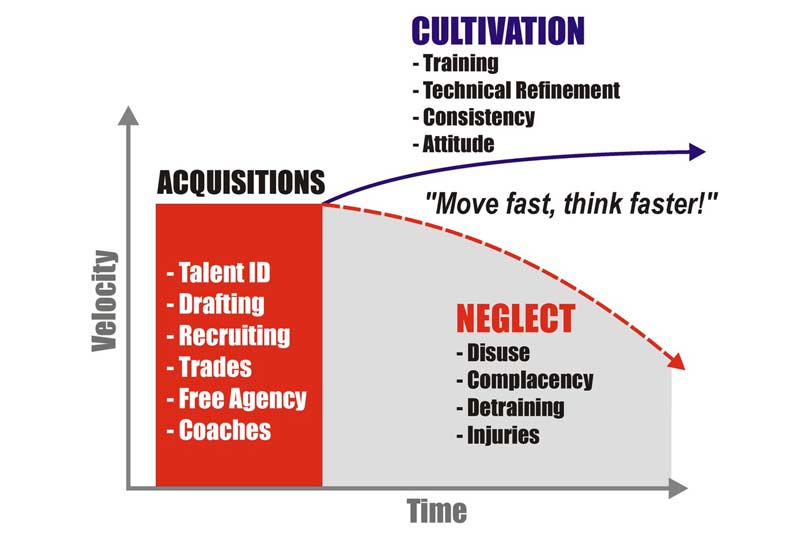

Anything worthwhile and sustainable takes time to cultivate. Overnight improvements are quite rare and, in sports where well-coordinated teamwork is critical for success, almost impossible to achieve. This is exceptionally true when developing speed, particularly at the team-wide level. But why does it take so long? Many variables and elements must be addressed on a comprehensive level for a team to be considered one of the fastest in the league that also can win a championship year after year. While some general managers and coaches may take an athlete-centered approach, this is only one piece of the puzzle. An attitude around speed development and application must be cultivated organization-wide to attain a critical mass of acceptance and buy-in that becomes systemically applied and considered around all decision-making.

We talk about the speed of movement, the speed of decision-making, the speed of recognition, the speed of communication, and the speed of thinking. Share on XHence, I’ve adopted an approach to change the organizational culture around speed when I work with various teams in both the professional and collegiate sport circles. We talk about the speed of movement, the speed of decision-making, the speed of recognition, the speed of communication, and the speed of thinking. Essentially—the speed of everything. Running speed is a good starting point as everyone knows who is fast and who is slow. It may cut as deeply as being chosen (or not chosen) back in grade school for a team by your peers. If you were fast, you were likely chosen earlier. If you were slow, playground natural selection quickly and brutally took its course. Modern technology has made us think about speed over everything. Speed of data transfer. Speed of production. Speed of delivery. Even the speed of meeting a new partner. Thus, speed must be all-encompassing and decisively adopted by everyone. So how do we accomplish this?

Why Focus on Culture?

These days, we often hear of leaders changing the culture of a company or cultivating a positive culture around productivity, innovation, and success. “It’s not just what we create, it’s who we are!” and other lovely memes circulate through the organization and appear in elevators and above urinals. Either you are for the culture or you are against it. The type of momentum generated by culture can be quite powerful and enduring. While some culture initiatives are simply corporate feel-good projects that never materialize into anything productive, a well-implemented strategy that has a positive systemic impact can truly vault an organization into a unique category of success. Some would say that Bill Belichick has instituted a culture of discipline, accountability, precision, talent identification, and strategic superiority at the New England Patriots that we can interchangeably superimpose on different personnel with similar positive results. Whether there’s an organization-wide culture initiative or a top-down dictatorship is up for debate, but the results are indisputable.

The term culture, as defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary, is as follows:

“The set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterizes an institution or organization.”

While culture can often refer to the customs, arts, and social institutions of a country, ethnicity, or community, sports organizations often discuss culture in terms of the dictionary definition, adopting attitudes, goals, and practices in the hope that success quickly follows. In business circles, corporate culture is deemed successful only if a business is also financially viable. Employee satisfaction, career longevity, community involvement, and other qualities can be part of that assessment, but if a business is losing money, it really doesn’t matter. In the same vein, a sports organization can have lots of happy players that get along with coaches and staff, sign autographs, and attend charity events. But if they aren’t winning, the organization will make changes sooner than later.

It’s important to point out that when instituting an approach that is adopted organization-wide—a culture shift—casualties can be incurred during the implementation. In the recent award-winning Netflix documentary, American Factory, a Chinese company acquired a former automobile factory in Moraine, Ohio, intending to turn the business around and make it profitable again as an auto glass production facility. With that in mind, the Chinese factory owners—who operated similar successful factories in China—instituted a change in the corporate culture that mirrored their previous ventures. Much of that culture revolved around the speed and volume of production, sometimes to the detriment of worker safety. Slower, less productive employees also were systematically fired as part of the transition.

Clearly, the key goal of the culture change was profitability and sustainability, not affability. The company offered significantly lower wages to the non-unionized employees, and job security was limited. But the factory was operational and providing jobs to individuals who were unemployed for three to four years previously. While this is not exactly comparable to New England Patriots players taking lower salaries in exchange for championships, culture can be exceptionally ruthless on the path to success.

While it’s all well and good to discuss culture and organization-wide change, it’s quite another thing to organize all of the pieces in a manner that yields progress. In the case of movement speed, there is no shortage of experts and gurus in the industry to show you new drills, equipment, biomechanical analyses, research papers, and fancy technology. But none of this matters if you don’t have organization-wide buy-in with everyone pulling in the same direction. Provided below is a list of requirements that give organizations a fighting chance to effect positive change around movement speed that applies to their finished product.

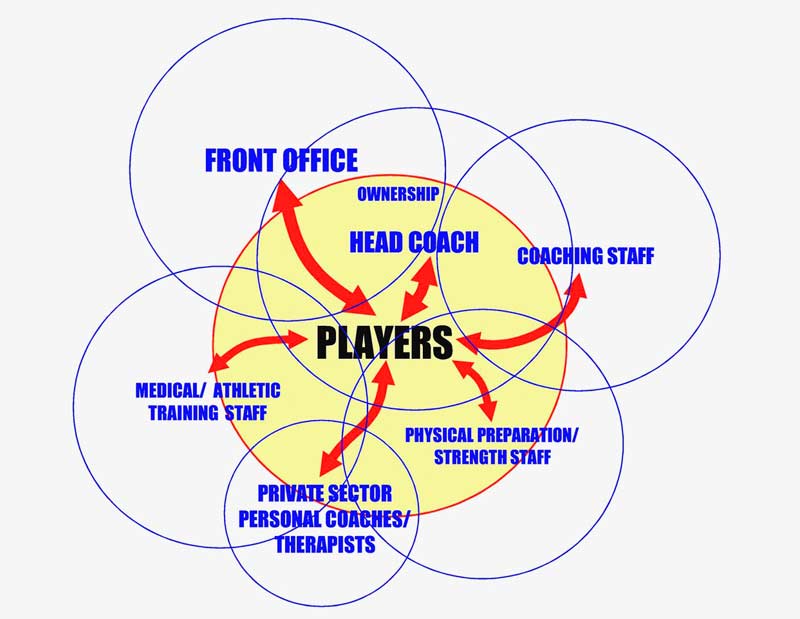

Personnel

When implementing a culture change, everyone must be part of the solution. It’s short-sighted to think that you only need to overhaul the players. Everyone in the organization must examine their role in increasing the speed of play as it pertains to developing a championship organization. You might be surprised how important the roles of front office executives, coaches, and staff play in cultivating an ecosystem of movement speed and everything that comes with it. The measures taken by all individuals add up to create a sum total of faster team play. While a race car requires a powerful, durable engine to attain the speeds necessary for victory, it also needs an exceptional driver, a fastidious pit crew, top-notch mechanics, and appropriate financing to ensure the team assembles all the critical pieces at the right time. The list below is not exhaustive, but it shows how the key pieces interact to maximize the possibility of improving a team’s overall speed capabilities.

Players

First and foremost, you do have to start with the players who make up your team. We have all heard the saying, “Sprinters are born, not made!” There is significant truth to this statement, and all teams and sport organizations should take heed. Selecting players who have the right combination of muscle fiber type, nervous system output, and compatible anthropometrics is critical for filling your stable with thoroughbreds. While we all like to think we can coach ourselves out of mediocre genetics, the bottom line is that biology is significantly more important than methodology. This is why all talent scouts need to arm themselves with a stopwatch in addition to their sport-specific wisdom. An athlete’s innate speed capabilities are the foundation upon which you will build other vital qualities and skills.

An athlete's innate speed capabilities are the foundation upon which you will build other key qualities and skills, says @DerekMHansen. Share on XWe often see and hear track coaches extoll the virtues of running track to prepare athletes for other sports. While I don’t disagree with this line of reasoning, I specifically like to watch athletes compete in Track and Field events because I can see them run over multiple, maximum output scenarios—a larger sample size upon which to evaluate their speed abilities per se. How do they run over shorter sprints? How do they run over longer sprints? How do they run after a bad start? How do they run in inclement weather? How durable are they over the length of multiple track seasons? How do they perform in high-pressure situations? All of these scenarios matter and provide much more information than two repetitions of a forty-yard dash at a combine or pro day.

Players not only need to be fast, but also need to have the specific conditioning to repeat high speeds consistently throughout the game. Legendary NFL strength coach Al Miller once told me that Jerry Rice’s brilliance was in his ability to repeat the same speed through the entire game. While he may not have had the glorious 40-yard dash times of Deion Sanders, he could wear down defenders with his superb conditioning. “He would run at defenders at his top speed throughout the first half of the game. By the second half, he didn’t slow down one bit, and the defensive back was at his mercy,” noted Coach Miller. This off-season preparation was entirely created by Rice’s legendary commitment to off-season training.

Flowing from the story of Jerry Rice’s unique accomplishments, an organization must choose athletes who understand the importance of maintaining the level of commitment to speed training and preparation that got them there in the first place. It’s very common to see athletes reach the professional ranks on their talent—often fostered by the discipline and structure of a collegiate setting—only to lose their edge and motivation once they start getting paid. Like the heavyweight boxer who worked tirelessly to the title belt, their work ethic and character can quickly fall off once they achieve a taste of fame and glory. Championship organizations need players who have longevity of motivation and ability to have a fighting chance to compete for the title year after year. This means consistent dedication to training in the off-season and maintaining health and ability during the season. Not every athlete has this level of commitment and character.

Traditionally, the faster players tend to be the newer, younger stallions who were honed by their college preparation and perhaps a career on the track team. Newer and younger also means cheaper. Once players have had time to develop a resume of stats and legitimacy, they’ve earned the right to demand more expensive contracts. It’s also a good bet that they’ve slowed down a step or two—de-trained from the diet of life as a pro and less urgent off-season preparation. While they may have gained valuable tricks of the trade, skills, and knowledge to help compensate for their speed loss, the net gain may be zero. Hence, a sound return on investment may require a commitment from these players to buy-in to the comprehensive approach adopted by coaches and staff. The right combination of fresh newcomers and well-maintained veterans under the right coaches can be very difficult to slow down from game to game, and it may be only a matter of time before a deluge of speed takes over the game.

Coaches

The obvious role of the sport coach is to place their athletes in positions to take advantage of their talents. A coach who doesn’t involve the fastest players in all aspects of the game will leave some very valuable cards on the table. From a purely strategic point of view, developing schemes and plays that put fast players in open space is critical for taking advantage of individual speed potential. Players with speed often can create something out of nothing. But to achieve consistent success, coaches must play a part in systematically creating opportunities for game-breaking plays using team speed. This can include disguising formations, creating misdirection, and using the occasional trick-play to keep the other team off balance. Once the opposition is thrown off balance, team speed can quickly shift momentum and drastically change the outcome of a game.

To achieve consistent success, coaches must help systematically create opportunities for game-breaking plays using team speed, says @DerekMHansen. Share on XSport coaches also need to work closely with strength and conditioning staff to make sure they’ve allocated an appropriate amount of time throughout the year to work on speed development. While this may seem like an easy ask, sport coaches are often overwhelmed with technical and tactical issues, always looking for extra repetitions or run-throughs to ensure they prepare their players adequately for impending competitions. Having worked with several teams on speed programming, I’ve found it’s always difficult to ask for a few extra minutes here and there to fit in high quality sprinting reps and the associated recovery time. However difficult the ask, you not only must do it, but you also must make the head coach aware of the need to allocate the necessary time to get the job done (i.e., make players faster). Sport coaches need to understand the time it takes to reproduce maximal sprint efforts for improvement to occur.

I remember being called several years ago by a professional sports team, and the strength coach told me they had 15 minutes to work on speed. He asked, “What can we program in that time?” I told them if they truly wanted to work on speed and had to warm the players up adequately, they would be lucky to get a few quality sprints in that window, given the recovery requirements of several minutes between reps. The strength coach replied, “Our head coach doesn’t want to see guys standing around for a few minutes between reps.” I could only respond with, “Well, I guess your head coach doesn’t want your guys to get faster.” This is the reality with most sports teams.

A few strategically placed recovery breaks goes a long way to increase the speed of practice & minimize the possibility of injury, says @DerekMHansen. Share on XSport coaches also need to understand how the demands of practice can slow down their players. The sheer density of drills and plays during practice can slow movement speeds significantly, and the steady accumulation of these types of practices has the potential to de-train speed abilities over the course of a season. A few strategically placed recovery breaks can go a long way to increase the speed of practice and also minimize the possibility of injury. For many coaches, however, taking their foot off the gas in practice is not part of their DNA. As the old saying goes, “Fortune favors the bold.” A new generation of coaches may start to understand the value of incorporating rest breaks in lieu of rehearsing plays that may never be used in game situations.

Performance Staff and Strength and Conditioning Coaches

Strength coaches are often characterized by their love of the weight room and all sorts of weightlifting equipment. It’s not surprising that a large proportion of strength coaches don’t feel comfortable teaching sprint training to athletes. Often, strength coaches use gym-based solutions instead of actual sprint training to work within their comfort zone. Recently, more performance staff have started recognizing the value of emphasizing speed training and have adjusted their approaches accordingly. Strength coaches with less aptitude have hired consultants to help with technical training and programming. I’ve been brought in on numerous occasions to teach team staff how to coach speed throughout the season. Gradually, an acceptance of the critical on-field requirements is taking hold among performance staff. But the amount of time, energy, and money spent on education, professional development, and equipment purchases still disproportionately favors the weight room.

We often hear that performance departments should simply hire track sprint coaches to teach athletes how to run. While this is likely an improvement over the “running” skillsets of traditional strength coaches’, it’s unfortunately not that simple. While every sport can benefit from linear sprint training, speed professionals must also understand the specific requirements and the culture of the sport with which they’re working. There are limitations within every sport that restrict the ability of conventional track training conventions. These limitations include time, space, athlete awareness, and the perception of coaches.

I’m sure everyone would love just to slap down some mini-hurdles and tell people to lift their knees. News flash—it ain’t that easy. I’ve been working with teams for over 20 years, and trust me, working with team sport personalities, schedules, and logistics requires a much different skill set. The ability to adapt methods and techniques to the sport-specific needs and desires of the coaches and athletes is imperative for success. You wouldn’t drop an Olympic weightlifting coach into a sprint training group without a chaperone present to blend techniques, translate terminology, and integrate methods progressively; speed professionals must become acclimated to the culture before making any significant contributions. And it may take many years before any significant changes that make it onto the field of play are minimally realized.

Medical Staff, Physical Therapists, and Athletic Trainers

Gone are the days of receiving a physical therapy treatment, hopping off the table, and running onto the field. Return-to-play (RTP) is not as simple as a handshake, a few warm wishes, and some crossed fingers. Every dot must be connected along the continuum from injury to recovery to the restoration of function to practice and, finally, to full competition. While some people like to use words like load management, I prefer to apply the basic tenets of progressive comprehensive training that prepare an athlete for the stresses and demands of their sport. Hence, medical staff must be part of the continuum of care and must understand the demands of high-speed running that could be addressed much earlier in the RTP process than previously thought. If these staff members do not understand the mechanics, velocities, and forces involved in the movements required for high-level performances, gaps in preparation will widen and place the athlete at risk of re-injury, never mind limit their output and overall performance capabilities.

Based on my own experiences in teaching both performance and medical staff at the highest levels, none of the skills involved in returning someone to high-speed running are discussed or taught in formal medical or rehabilitation science university programs. Time and effort must be taken to equip these professionals with the tools to not only understand what they need to do but also the abilities to conduct the protocols and training sessions on their own. Some of the work could be performed in a clinical setting, with medical staff gradually moving to the weight room and field environment soon after. In some cases, athletes could be handed off to performance staff as part of the continuum of care with both parties speaking the same language to discuss the choices to date and pinpoint the next steps in the process. Such a seamless process will not only build athlete confidence in team staff but also ensure that no stone is left unturned in the RTP journey, maximizing the potential for both durability and sustainability.

Front Office

Front office executives often work hand-in-hand with coaching staff when identifying talent and choosing players in drafting scenarios, free agent signings, and trades. While every team may have different means of determining needs, it’s assumed that most successful teams draw up short-, medium-, and long-term strategies around player acquisitions that fit into their coaching style and within their salary cap. When adopting a team-speed approach, front office executives must have a strategy that identifies players who have appropriate speed abilities as well as the sport-specific skills, mindset, behavioral traits, and teamwork qualities that fit with their vision for the organization. The executives who can identify, acquire, and integrate the players with pure speed ability and the sport-specific skills to go with it will undoubtedly give their team an upper hand.

The team must also have a significant degree of depth when it comes to the speed of personnel. Competition in training camp and practice must bring out the high-speed capabilities of each and every player. If only a handful of players on a team are fast—with the average speed of the roster hovering at mediocre—the speed at which practice is carried out can be much lower and impact the reflexes and anticipatory skills of each player. Teams often strive to practice as they play, but slower speed in practice will almost always lead to the same result at game time. Thus, it’s critical the front office executives strive to acquire players that are fast at every position and throughout the depth chart.

Legendary ice hockey player—Wayne Gretzky—had notable on-ice speed. And he was surrounded by teammates who could easily match him on the ice—such as Paul Coffey, Mark Messier, Glenn Anderson, and Jari Kerri—and mesmerize opposing teams with their speed and skill. There is great video footage of Gretzky beating other top athletes, including soccer star Pele and tennis phenom Bjorn Borg, in sprinting competitions in Sweden back in the early 1980s. Clearly, organizations can only benefit by surrounding speed with more speed.

Ownership

The team owner is as important as everyone else in the planning, decision-making, and implementation chain when it comes to the team culture around speed. First and foremost, there is a financial commitment that’s implicit when seeking out the appropriate players for the roster. Renewing contracts, signing free agents, and scouting new talent efficiently all take significant resources. The right coaches must be in place to implement a system and series of programs that can maximize the abilities of each player on the team.

On the infrastructure side, owners must provide the necessary facilities for accommodating a speed-based approach. On several occasions, I’ve been contracted to guide the design and construction of ramps and hills for resisted speed training within the confines of a practice facility. This is not a small endeavor and requires the approval of budgets as part of a long-term vision. Finally, these facilities need to be outfitted with the appropriate advanced technology to track and monitor progress from session to session and networked accordingly to allow for quick analysis, review, encryption, and storage.

In some cases, ownership may choose to be stingy with spending on building the correct roster, let alone committing to a long-term approach for player development. Many professional teams turn a profit from simply being in a league full of talented, outspoken athletes. If the home team isn’t faring well for a season or two, fans still show up to see stars from visiting teams and still buy beer, burgers, hot dogs, nachos, and player jerseys. Television revenues also maintain profitability for owners and paying for “extras” that may or may not yield post-season success is not always considered a wise financial strategy. The mindset to create the potential for any distinct advantage over the competition must be hard-wired from the top down to give an organization a fighting chance for a championship.

Private Sector Service Providers

One often overlooked area that’s part of the big picture of speed development and maintenance is the private sector coaches and performance professionals who work with players in the off-season. Because most professional sport collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) limit the amount of time team staff can spend training players—with some pro sports not allowing any significant monitoring of player off-season activities—coordination and integration of contributions made by private sector professionals is critical for an organization’s continuum of care. The pro team must make efforts, within the rules of the CBAs, to communicate and share information with service providers throughout the year to build trust, disclose important information, and demonstrate a willingness to work together toward a common goal.

There will always be a handful of players who choose to do their off-season work with a personal coach or trainer who simply wants to entertain them. Organizations, however, must recognize that the majority of private coaches have a vested interest in seeing the process through to a championship and the individual accolades that can come from it. Teams also need to allow for creative license in implementing off-season work, assuming the general goals of the off-season physical preparation are agreed upon. A team built on a foundation of speed can only expect that the off-season activities of individual players should include a reasonable amount of speed work outside the gym environment. The onus is on both sides to work together for the benefit of both the athlete and the team. As with any relationship, time must be allotted for gradual growth and mutual respect. As with every element concerned with speed, this is not an overnight proposition and may take years to cultivate and optimize.

Programming and Planning

Once the proper infrastructure and personnel are in place, programming becomes one of the easier components to design and implement when cultivating a broad-based culture of speed. The different times of year have varying opportunities and constraints that all coaches and staff must take into account. A team with a well-developed culture around speed will take advantage of the entire year to maximize opportunities for improving speed and the practices of various stakeholders, and not simply put their chips on one number and hoping for results. Diversifying your speed training approaches is necessary for the volatile market of high-performance sports.

Off-Season

Depending on your sport, level, and professional league, the off-season may present either a significant opportunity to improve speed or a major obstacle to working with athletes. As a team or professional organization, you can mobilize staff and implement a comprehensive approach to consistent training for speed that will ultimately mesh with your in-season strategy. However, if players’ unions and CBAs limit coaching time with your athletes, the off-season may not be the best time to mount your assault on mediocre sprint ability. If player participation in the off-season period is lacking, it may be the best time for coaches and staff to meet and formulate a reasonable pre-season and in-season plan around optimizing team speed.

For teams that have the opportunity to accumulate a significant number of sessions dedicated to speed development in the off-season, emphasizing quality and consistency will pay substantial dividends throughout the rest of the season. Acceleration abilities are the highest priority for training, as most sports involve relatively short accelerations repeatedly throughout a game or competition. While some programs will focus on endurance and general conditioning, accumulating hundreds of acceleration repetitions over 10-20 meters will build specific endurance qualities for accelerating. I’ve seen this work first hand, and I’ve even watched it significantly improve the results of evaluation protocols geared toward aerobic interval testing. Knowing what type of work carries the biggest bang for your buck is critical when you’re constantly squeezed for time in team sport settings. Understanding that ideal conditions will never be available for your off-season programming is the first realization to make before you achieve any progress—however minute.

Pre-Season

The pre-season is rife with sport-specific demands, many of which can quickly exceed the capacity of every player if left unchecked. Strategic objectives and player evaluations take priority over all else. Endless repetitions allow for the installation of the “system” and weeding out players who cannot survive or fit into the speed and precision of everything. Because the bulk of energy and tissue resiliency are dedicated to these sport-specific demands, you must dispense any additional loading of a high-intensity nature very carefully with surgical precision.

You cannot overcome deficits in such a volatile, short-term period, but you can reinforce technical norms through activities prior to practice, such as in the warm-up sessions. Traditionally, warm-up activities—even the so-called dynamic warm-ups—hover in the low- to medium-intensity range at velocities and rates of force development that do not resemble what will take place in the heat of battle. A combination of fear and complacency can quickly take hold when you could easily achieve productivity with a few simple changes. Moving into more intense activities such as linear accelerations from various start positions can encourage adaptability and hasten readiness in these shorter warm-up periods with minimal risk to athletes if progressed appropriately. Imposing such a demand will have a positive effect on readiness and, more importantly, overall preparedness over numerous sessions during the pre-season period.

In-Season

In professional sports, the in-season period can become a very attractive domain for effecting changes and maintaining qualities above and beyond what at “typical” team attempts to accomplish. However, readiness and recovery seem to be the rule of the day, with fancy terms such as load management popping up more and more. Many people assume that rest and even more rest is the solution to every problem—performance deficits, injury problems, and athlete discontent. And that performance staff are unaware of the sinister effects of de-training that may occur with multiple systems—systems not appropriately stressed through practice and competition alone.

As with the pre-season scenario, you can plan warm-ups to include discrete amounts of speed work. A well organized in-season program will also include at least one session per week where you can accomplish a more ambitious attempt at consolidating speed work. If combined with a sound practice plan that gives players opportunities to hit higher speed in a sport-specific fashion—taking advantage of open space—teams may even experience speed improvements as the season progresses. For the in-season period, my experience shows “Fortune favors the bold” in that those who push the boundaries are destined to be rewarded while those who continue to back off will eventually find themselves pinned to a wall.

Post-Season

If you take the correct measures for developing and maintaining speed for the rest of the year leading up to the post-season, you’ll have very little work to do to reap the benefits. Of course, it’s only advisable to maintain some of the same routines established in the regular season once the post-season comes around. Nobody wants to peak too early; the free fall from a premature de-loading effort can be unrecoverable both physiologically and psychologically. The post-season hopefully becomes a validation of all of the well-measured training stresses you’ve imposed throughout the year.

Professional Development

A change in culture often involves facilitation, encouragement, and guidance along the journey. It might seem easier to simply change the entire staff to fit your vision for a team. However, upgrading the “software” with the current staff is often all you need, particularly if everyone gets along and has developed trusted relationships with the team’s top players. Professional development is an important commitment, but often the commitment is fragmented, planned at the last minute, and lacks overall coherence in relation to organizational goals. “Flavor of the month” professional development events are common, with staff picking their preference of who they want to see. During one off-season, it may be manual therapy techniques, the next year it’s load management practices, and next year it will be virtual reality for performance and rehab. While I understand the allure of variety, at some point you have to focus on consistency and hone specific skill sets that will translate into results over the long term. While this may not seem like an exciting approach to professional development, it is absolutely necessary in the pursuit of mastery.

Creating a long-term professional development plan within a professional sports organization seems like a naïve concept, given that time in pro sports can be short-lived. I argue, however, that front office executives would embrace employees who had a long-term vision and developed a plan around meeting those goals in an ambitious, albeit realistic fashion. Sports dynasties are not born overnight; they’re developed through careful management of variables over time, evolving every year. It’s so easy to attribute wins to personnel and talent alone. However, longevity requires that everyone working under the same roof has deliberate intent to get better every game, every week, and every season for the duration of their tenure. A focused, long-term continuing education plan must be part of that intent.

Marketing and Promotion

Faster game play in most sports is often much more entertaining than either a defensive-minded or blue-collar approach to competition. Even when slow, patient, and deliberate works regarding the scoreboard, it’s incredibly tedious and boring. There is a reason basketball has a shot clock, football has a play clock, and delay of game penalties exist. Moving fast is intrinsically appealing and looks better to the human eye. Professional leagues are now using technology and data to emphasize players’ speed on the field with wonderful dashboards and graphic displays that point more to gamification and celebration of elevated metrics. The NFL Combine may not be an integral part of draft research for individual teams, but as a promotional event, it attracts a good amount of attention and places speed front and center. Even Rich Eisen is dedicated to running faster every year in the 40-yard dash as he passes the half-century mark.

Once a team has speed, show it to the world. Speed propaganda is an untapped element within the cultural ecosystem, says @DerekMHansen. Share on XOnce a team has speed on its side, it makes good marketing sense to show the world the fruits of their labor. The team knows it, the fans know it, and more importantly, it’s embedded in the minds of the opposition every time they step into the competition arena. Perception becomes a reality, and everyone changes the way they think about that team. If you say it enough, people start to believe it. Speed propaganda is an untapped element within the cultural ecosystem.

Concluding Remarks

While I expect more people to start talking about the culture of speed (or maybe even the culture of load management) very soon, I challenge them to fully define what they envision and how they will implement it broadly and effectively. Just as we’ve seen from the people who have become overnight gurus in the art of micro-dosing training (it took me about 20 years to label and refine the concept), we quickly realize that talk is cheap and results speak volumes. If you have truly implemented a broad cultural approach to speed, you will clearly see the results demonstrated week to week so that everyone can see it at the stadiums and arenas and via live streaming broadcasts. Walking the walk takes years of planning and development, while talking can occur instantaneously. Choose wisely who you follow.

I’ve built my professional development courses upon decades of trial and error around the integration of speed techniques with tens of thousands of athletes and almost every sport conceivable. A large sample size of experiences is extremely valuable in helping you navigate through all the potential challenges and crises experienced in sport every day. The various modules of the Running Mechanics Professional (RMP) courses are a building block solution to comprehensively integrating a speed-based approach to all types of sports at all levels. We discuss the interactions you’ll have with all potential stakeholders—athletes, coaches, parents, administrators, physical therapists, doctors, psychologists, and scientists—in your quest to slow down time and speed up movement. A strong culture involves a common language, customs handed down from generation to generation, an appreciation of art, and strong leadership throughout. It does not matter what individual qualities you want to improve in a person or organization, as they still need to be surrounded by a profusion of supportive elements to ensure both quality and sustainability.

While many people will continue to put forth exercise-based or data-driven solutions, the advanced specialist will understand the exceptional importance of ecosystem building and relationship cultivation that forms the foundation of any speed-centered initiative. My personal experience over the last few decades continues to confirm this approach and will ultimately outlive my career. I desire to impart this knowledge to those who genuinely want to immerse themselves in a culture-based approach. Coursework is simply the start of this relationship—an ignition point. Ongoing ecosystem development and management is a lifelong endeavor.