Aaron Cunanan is currently the Minor League Sport Science Coordinator for the San Francisco Giants. He completed his Ph.D. in Sport Physiology and Performance at East Tennessee State University in 2019 and his master’s degree in kinesiology from LSU Shreveport in 2012. Aaron served as an assistant coach and the lead sport scientist at the Olympic Training Site at ETSU for weightlifting and completed a strength and conditioning internship at the UFC Performance Institute in 2018. Prior to ETSU, Aaron was an assistant coach under Dr. Kyle Pierce at the USA Weightlifting Center for High Performance and Development in Shreveport, Louisiana, from 2010-2016.

Freelap USA: The isometric mid-thigh pull is certainly not new, but coaches constantly try to refine this test to get athletes comfortable providing a maximal effort. What practical advice do you have for those wanting to add this test into their program besides the obvious need to follow the protocol closely?

Aaron Cunanan: I’d say proper positioning, secure grip, and appropriate cueing are three must-haves for a good test.

Proper positioning is key from both a performance and safety standpoint. Establishing a good position during the initial test and maintaining consistency during subsequent tests are critical for using the test for any sort of monitoring purpose.

After positioning, grip becomes the biggest limiting factor. Taping the hands to the bar may be a non-starter in some settings, so I’d recommend the use of straps and chalk at a minimum.

As for cueing, the consensus is to first cue speed and then strength to get the best RFD values. For example, “Pull as fast and hard as possible” or something along those lines that makes sense to the athlete.

One bonus tip I’d give is to cue your athletes to shrug their traps during the test. I’ve seen this cue increase peak force by several hundred newtons or more during a trial.

A bonus tip I’d give is to cue your athletes to shrug their traps during the IMTP test. I’ve seen this cue increase peak force by several hundred newtons during a trial, says @aaronjcunanan. Share on XIt’s great that more coaches are realizing the value of this test, and I’m excited to see the variations that will emerge as practitioners optimize the test for their environment and constraints. I expect we’ll see alternative tests, like the isometric belt squat, become more common, especially in those sports where upper body soreness or injury are a common concern.

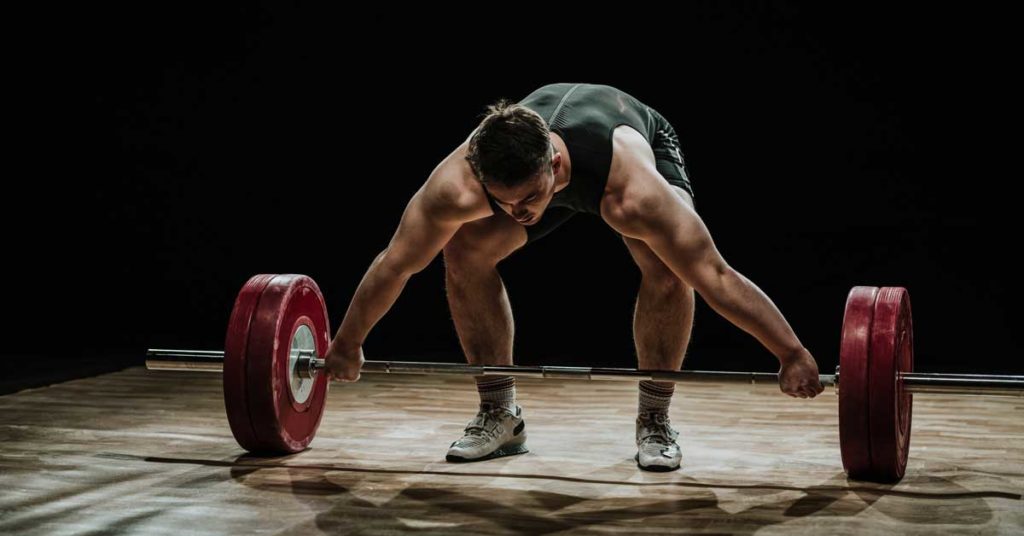

Freelap USA: Barbell path matters in both the sport and getting more transfer out of the weightlifts. What coaching recommendations do you give athletes to ensure their bar path improves over time?

Aaron Cunanan: In general, I coach my athletes that the bar should move toward them continually during the first pull, not away. If the bar is out in front once it gets to the knees, then the athlete’s balance will probably be too far forward. This position is tough to recover from, especially in newer or weaker athletes, and severely compromises their ability to produce vertical impulse during the second pull.

If the athlete is in a good position at the knees, I find the cue to “keep the bar close” once it passes the knees clears up a lot of mechanical issues by the lifter from the end of the first pull to the completion of the lift. For example, it’s practically impossible to execute the double-knee bend properly if you don’t keep the bar close.

Keeping the bar close as you arrive at the power position also puts you in a better overall position to produce vertical impulse during the second pull. Finally, focusing on keeping the bar close during the turnover phase (as you and the bar move into the catch position) helps to minimize the amount of horizontal loop. A smaller horizontal loop is more strongly associated with successful versus unsuccessful lifts1 and higher caliber lifters1,2.

I also reinforce these cues and concepts during any pulling variations included in the program, like pulls to the knee or pulls off the blocks from the knee or power position.

Freelap USA: Clusters as accentuated eccentrics are methods that coaches are experimenting with more and more. How do you recommend a coach use an appropriate load if they utilize weight releasers?

Aaron Cunanan: Research continues to demonstrate the benefits and applications of cluster sets, but we’re just starting to scratch the surface with direct studies on the effects of different accentuated eccentric loading (AEL) applications. However, I think it’s natural for shrewd coaches to try find ways to combine the two approaches effectively.

A logical starting point for combining clusters and AEL would be during power-oriented phases closer to the competitive season. A study by Wagle et al.3 that looked at the acute effects of cluster-AEL sets provides some support for this approach.

I’d speculate that cluster-AEL sets might also be effective if implemented as part of a planned overreaching strategy for 1-3 weeks prior to more traditional programming during the power phase. As with most things, scale volume, intensity, and phase duration with the experience and training status of the athlete.

I should emphasize that much of the current rationale for AEL applications is theoretical at this point, and AEL is an advanced training tactic that we should reserve for athletes who have already developed at least above-average strength.

Freelap USA: The rate of force development is a limited metric without the interpretation and context of other measures. For injury reduction, how do you see RFD being used to help with the non-contact ACL tear?

Aaron Cunanan: More and more people are starting to realize there’s no single metric that tells us the whole story. This realization is leading to an important shift in the industry toward long-term monitoring.

Serial testing in a long-term monitoring program still lets coaches evaluate the results of individual testing sessions to see how their athletes stack up during key points of the year, but it has the added benefit of allowing practitioners to create individual baselines and movement profiles to evaluate change.

Furthermore, looking at clusters of variables instead of individual ones gives you the ability to look for patterns consistent with a given outcome instead of falling down a rabbit hole by focusing on a single metric. Having a cohesive set of variables to look at gives practitioners more solid footing to help decision-making related to setting training goals, evaluating training responses, and assessing athlete progress, and during return-to-play scenarios.

RFD is a tricky measurement because, while it’s responsive to training and fatigue, it’s somewhat noisy. Taking RFD values from dynamic tests, like the countermovement jump, can be especially problematic, so using isometric tests to look at RFD alongside impulse or force is a good place to start.

Another measure that has similar issues with reliability is asymmetry. Chris Bishop has really helped to pull back the curtain on asymmetry testing recently, but I do think asymmetry measurements can be useful if you take an individual approach and include them alongside other measures.

The ability to identify variables from different tests that make sense to look at together is one way that practitioners can really make themselves stand out, says @aaronjcunanan. Share on XThe ability to identify variables from different tests that make sense to look at together—which is different than throwing stuff at the wall and seeing what sticks—is one way that practitioners can really make themselves stand out. But be wary of the guru or company that claims to have it all figured out.

Freelap USA: Now that you are in baseball, what do you anticipate professional sports will learn from Olympic sport with science and technology? Do you expect more adoption of science and best practices in the future?

Aaron Cunanan: A common trait I’ve noticed in those coming from Olympic sports is they view training as a long-term process that requires integration across many disciplines.

Olympic cycles are four years with performances throughout the quadrennium directly impacting eligibility and selection for the Games, not to mention the years of development to get to that point. This scenario necessitates a long-term perspective, and it’s a given by now that it takes a concerted effort across all areas of performance—S&C, nutrition, sports medicine, sport psychology, etc.—to have any chance at success.

I think coming from that environment is particularly useful in sports like baseball where there is an extensive developmental system, including baseball academies in the Dominican Republic that take in athletes as young as 16. Player development is an important part of the sport, so I constantly look for opportunities to apply that long-term approach in my current role.

I think the biggest areas for the evolution of sport science in baseball over the coming years will be better benchmarking for the demands and characteristics of the Big Leagues, refining talent identification, and monitoring of player development.

Regardless of sport, I think sport scientists can make an immediate impact by providing quality assurance for testing and monitoring (and the implementation of sport technology) and finding ways to support collaborations between and within departments.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Stone, M.H., O’Bryant, H.S., Williams, F.E., Johnson, R.L., & Pierce, K.C. “Analysis of bar paths during the snatch in elite male weightlifters.” Strength and Conditioning Journal. 1998;20(4),30-38.

2. Cunanan, A.J., Hornsby, W.G., South, M.A., et al. “Survey of barbell trajectory and kinematics of the snatch lift from the 2015 World and 2017 Pan-American Weightlifting Championships.” Sports. 2020;8(9):118. doi: 10.3390/sports8090118.

3. Wagle, J.P., Cunanan, A.J., Carroll, K.M., et al. “Accentuated eccentric loading and cluster set configurations in the back squat: a kinetic and kinematic analysis.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2018. doi: 10.1519/jsc.0000000000002677.

Hi Coach, my son Peyton train under Dr Kyle Pierce. He is 11, and he has been training almost 3yrs. Dr Kyle has been very great with Peyton he and Coach Josh at the Lsus Shreveport Weightlifting Program.