A few years back, based on training an athlete with unique and extremely challenging physical circumstances, I had a happenstance introduction to offset loading. Prior to this, I had only seen offset training practiced in very remote corners of strength and conditioning—and while I was intrigued by what I saw, I could never wrap my head around the method’s practicality.

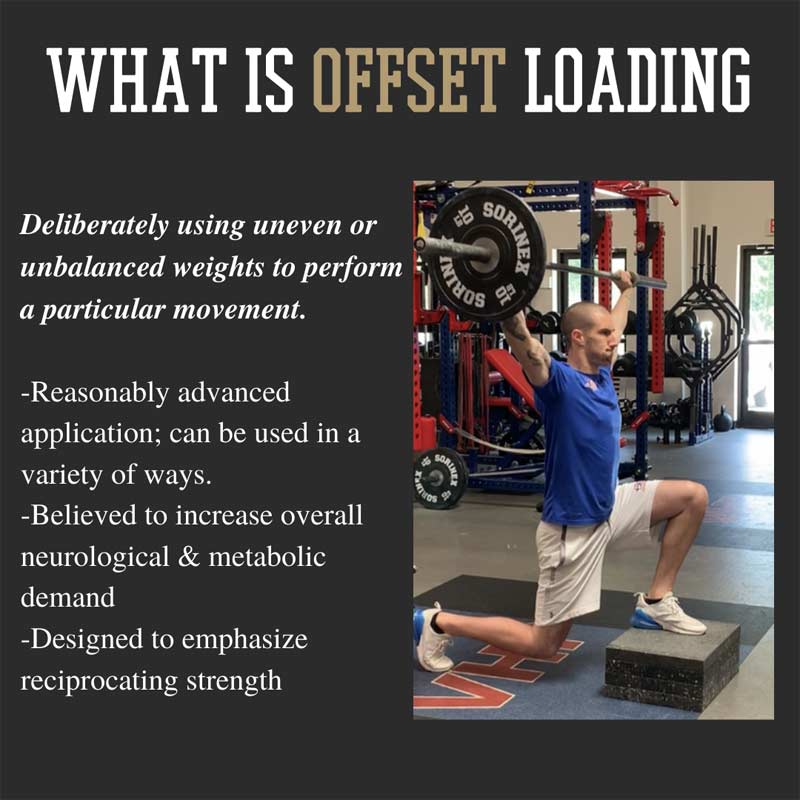

Offset loading is a somewhat unorthodox (or dare I say, nuanced) training application that can be performed in a variety of ways, but it most prominently involves intentionally loading each side of the barbell with moderately different weights. When progressively implemented and programmed appropriately, offset training can offer significant benefits to the right population.

For the sake of transparency and provisional safety, there are a few issues I want to quickly address:

- This article will exclusively include anecdotal evidence. In fairness, there is virtually no formal research to validate offset training. (This is one of the few formal studies I’m aware of.) So, for my sport science crowd and those coaches and practitioners who live and die by what the research says, I regret to inform you that this article may leave you uninspired at best.

- Although I’ve personally had success using this application, it’s important to understand this is not a form of training all individuals should utilize or all coaches should implement. There is a certain level of foundational strength and training proficiency (as well as coaching competency) that should be established prior to using offset loading.

- While I am writing this for conventional sports performance, I have personally only utilized these methods with high-level Special Ops/Special Forces athletes, so to an extent this will be somewhat of an outsider’s perspective.

With that all said, I am confident there are several ways offset work can be just as pragmatic for the sport world as I’ve recognized with the tactical realm.

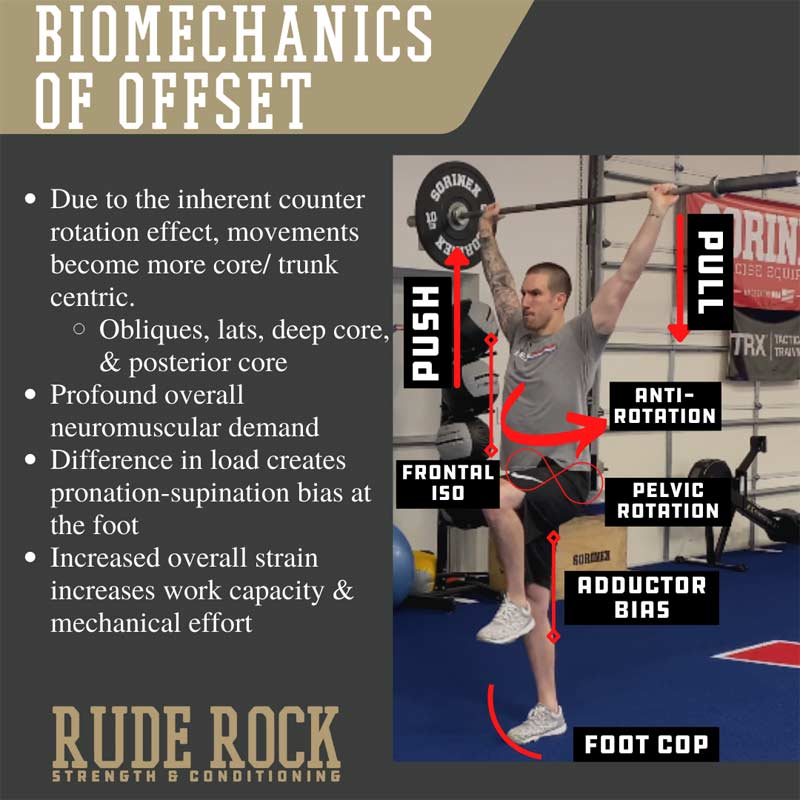

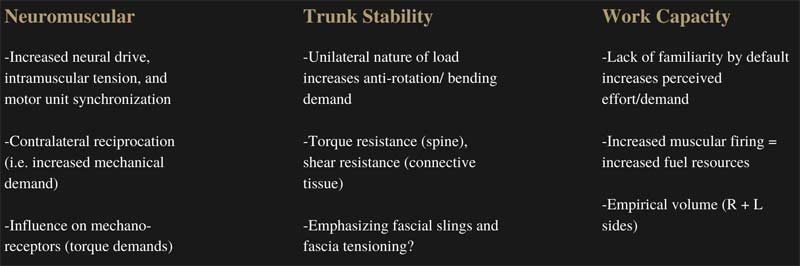

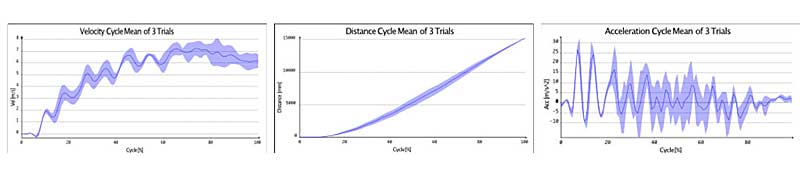

Over the last three years, I’ve been selectively implementing and investigating offset loading with a wide spectrum of individuals. In theory, the distinction with offset training is that it increases the overall demand on torque management (joints/ligaments) due to the inherent counter-rotation. The unbalanced load also puts a greater emphasis on trunk stability and deep core muscles.

By applying offset loading over the years with my athletes, I’ve seen significant improvements in hypertrophy, strength, general motor control, posture, and positional integrity, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XAdditionally, offset training is significantly demanding neurologically, so there is somewhat of a higher “bang for your buck” type of return. By applying offset loading over the years with my athletes, I’ve seen significant improvements in hypertrophy, strength, general motor control, posture, and positional integrity—results notable enough that I’m convinced the method isn’t just a novel gimmick performed for social media clout, but that there is absolutely something to this.

Offset Training 101

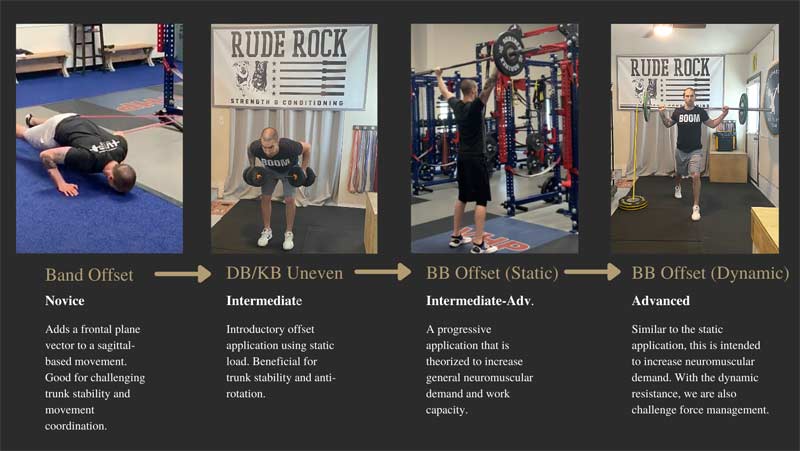

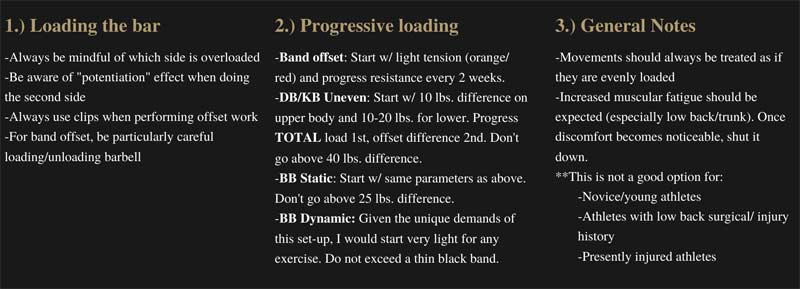

There are multiple ways you can apply offset loading, but my four primary applications are:

- Band offset.

- DB/KB uneven.

- BB static offset.

- BB dynamic offset.

I generally introduce and progress offset loading in that order, and each of these has its own nuances. But in addition to the benefits outlined above, I’ve found offset training to be highly effective for reducing the margin of difference between dominant and non-dominant sides (e.g., throwing athletes, athletes returning from extremity injury).

Video 1. Moving from an offset overhead march through a sequence of movements involving counter-rotation, with key coaching points and cues.

Offset training is very simple to work into your programming and can be highly effective for athletes once foundational strength has been developed. (For a full YouTube playlist of 55 offset loading exercises, click here.)

It should be clear that offset training is a modality that needs to be earned, especially the barbell applications. While the band offset and DB/KB uneven applications are reasonably low risk, I would not advise using the offset barbell applications until a robust foundation of strength has been established.

The main consideration with offset loading is the increased shearing stress it places on the spine and working joints, when compared to symmetrically loaded movements. Given the difference in weight between the left and right sides, the athlete will be required to fight the urge to be pulled out of position as they execute the movement (hence, counter-rotation).

The main consideration with offset loading is the increased shearing stress it places on the spine and working joints, when compared to symmetrically loaded movements, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XProgramming Factors

Offset loading is not something I would suggest as a mainstay, but more something that you can phase in and out throughout the calendar training year depending on your sport/population. From a macro view, I think using offset loading intermittently—but strategically—can greatly benefit athletes.

One such instance would be using a high-volume method during off-season/accumulation periods to drive overall work capacity/volume; another good opportunity would be for primary lifts during phases of the in-season period. In the latter case, the goal of offset loading would be to stimulate neuromuscular demand while not overtaxing the joints with heavy compressive loading. This can also be applied situationally, and sports that are more extreme in unilateral dominance may benefit from more offset programming.

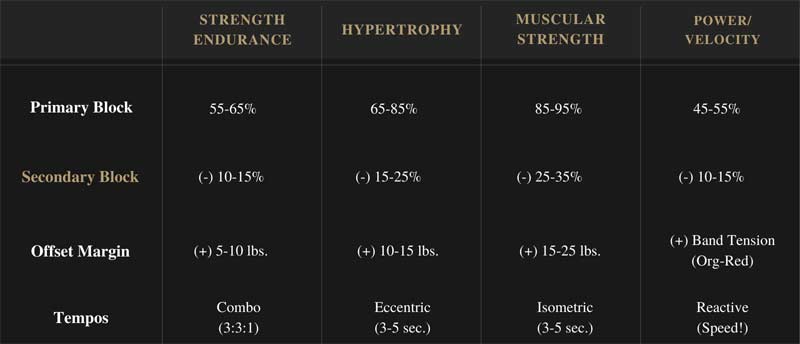

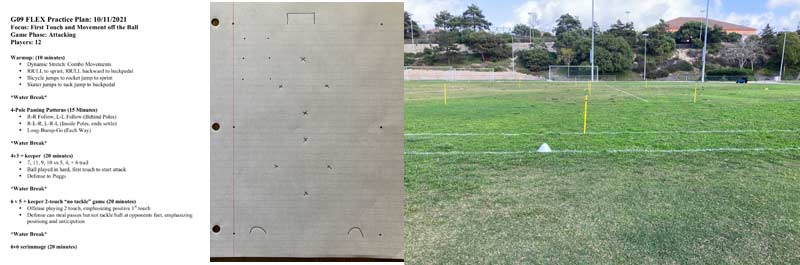

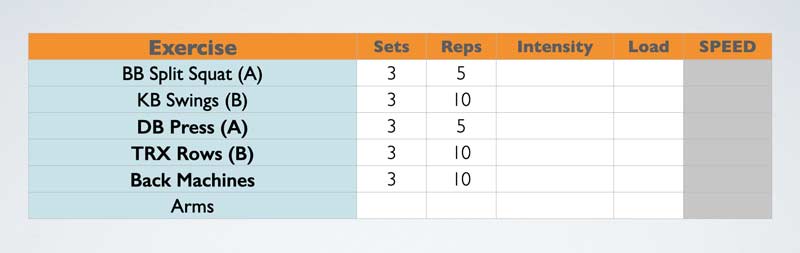

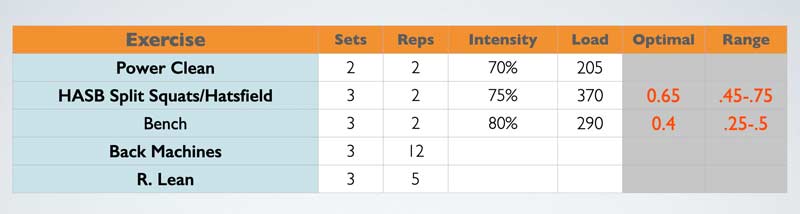

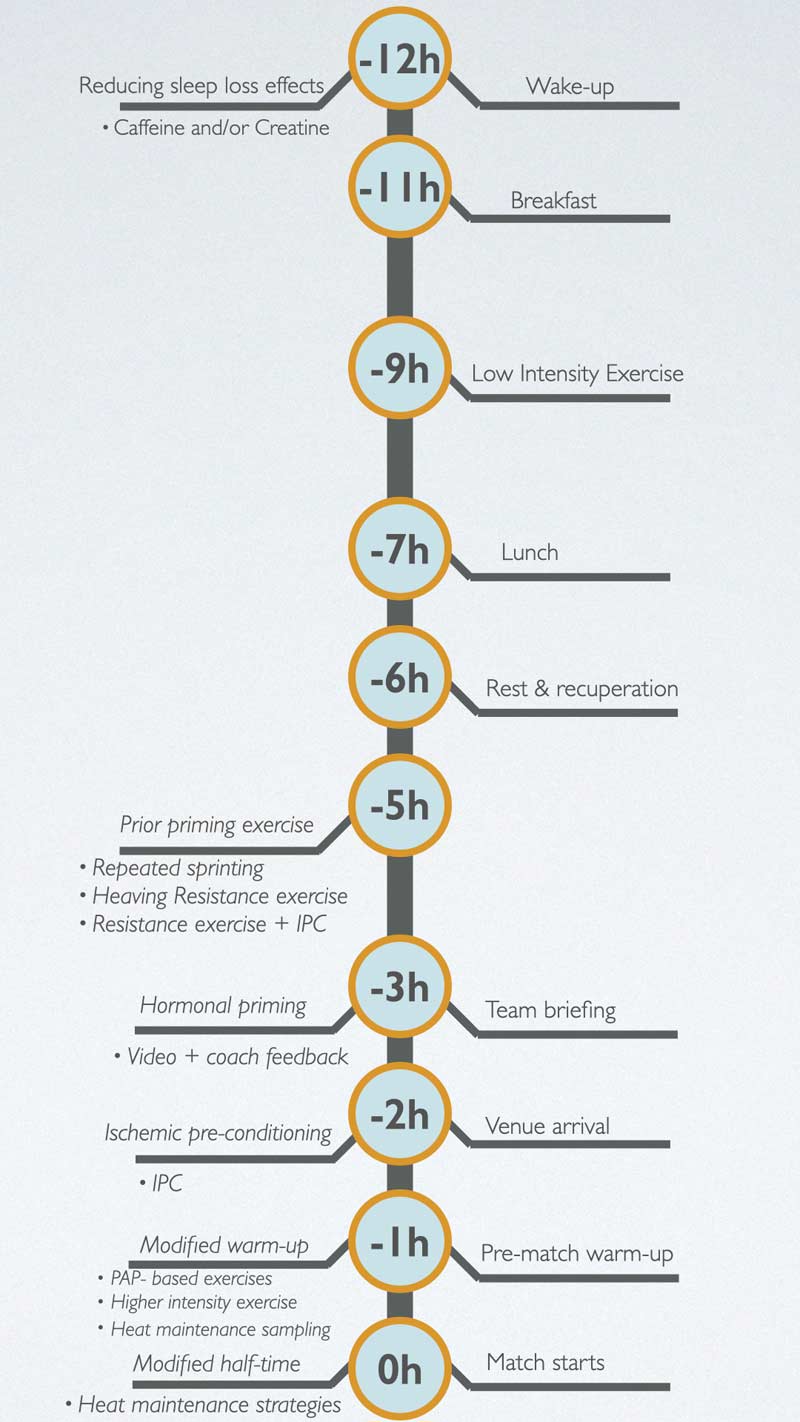

On a micro (daily) view, I normally get most of my offset work during the second block (see above). The most effective way I’ve found to program this is to perform the same lift that I had in the primary block (e.g., bench/squat/dead/push jerk), but reduce the intensity and rep count. I also typically apply tempos to offset work. The progressive overloading should be small and incremental. I would encourage you to increase the offset value (e.g., a 10 pounds offset to 15 pounds) first, then increase the total load. Obviously, the specific increases would be dependent on the specific exercise/athlete.

Given this article is directed more specifically toward the sport population, please check out a (free) recent webinar of mine that covers a more thorough explanation of the “101” for offset loading. But with that, let’s now pivot to some more sport-specific benefits.

Neuromuscular and Proprioceptive

The first perceived benefit that comes to mind is the potent neurological stimulus created by offset loading. Due to the unbalanced external load, there is a significantly greater demand for intrinsic stability, as compared to evenly loaded movements. Indirectly, I believe this increases neural activation due to the demand for more co-contraction and, thus, overall muscular activation.

The demand for intermuscular coordination is high with offset loading, and simply put, more muscles being called to duty would theoretically suggest overall motor unit recruitment is increased as well: think of this as greater global force summation. This is certainly beneficial for all athletes, but especially those who are coming off injury (poor kinetic integration).

An important caveat here is that the overall demand on the CNS with offset loading can be achieved at significantly lighter total loads when compared to the same movement bilaterally loaded, with the benefit then being that athletes can achieve similar neuromuscular efforts without as much compressive force being imposed. This can be specifically advantageous during in-season programming when time is limited and athletes are accumulating wear and tear from competition.

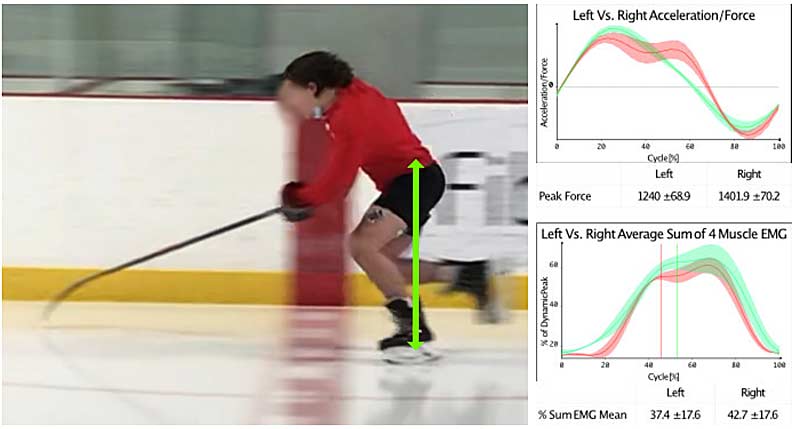

In and of itself, strength is very contextual and environmentally driven. While the importance of foundational strength by way of the conventional lifts is inarguable, I strongly believe we become overzealous with big numbers on big lifts while neglecting the variability of strength demonstrated in sport. Not only are pure strength and stability demands in sport almost entirely unilateral, but also much more reflexive and responsive by virtue.

Video 2. Barbell offset reverse lunge to step-up.

One of the best sports to illustrate this point is combat sports (e.g., MMA, Muay Thai, boxing). Think about the intricacies of striking, bending, and grappling, and how these athletes’ bodies maneuver around the cage. Constantly shifting center of pressure; always tracking and repositioning in accordance with their opponent. And, of course, the way in which forces are being applied and expressed when engaging their opponent. It doesn’t take much analyzing to observe the lack of symmetry in sport.

Offset loading promotes a general increased proprioceptive demand, as the body must heighten sensory systems to coordinate the movement and load application, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XRather than simply asking “how strong is strong enough,” the question really becomes: can you respond fast enough, orient your body accordingly, and then exert the requisite expression or resistance of force? As such, offset loading promotes a general increased proprioceptive demand, as the body must heighten sensory systems to coordinate the movement and load application. I would argue confidently that the proprioceptive demand is more applicable for most athletes than simply pursuing bigger numbers.

Torque Management

Due to the increased presence of torque, it would be reasonable to assume that the mechanoreceptors (joint receptors) are in a heightened state during offset loading. An increased torque demand means there is a stronger presence of shearing moments for working joints. If we examine injury reports across all major sports, we see some distinct similarities in both mechanism and types of injury. Among those similarities is a high rate of soft tissue injuries, particularly ligamentous injuries. Very bluntly, ligaments do not accommodate shearing stress well (rotational forces), as ligament injuries occur when the rate of external force is applied faster than the body’s ability to respond to it, or the force is applied in a manner or vector for which the body isn’t adequately prepared.

Remember, if it were as simple as an ACL tear being a consequence of insufficient force tolerance/expression, non-contact injuries would never occur and every athlete would just train like a powerlifter. But, as we know, this isn’t the case. Thus, I believe one of the most effective things strength coaches can do for their athletes is improve their ability to tolerate torque—and offset loading requires an inherent tolerance for managing shearing stress.

Video 3. Some fundamental differences between offset and bilateral loading in the same exercises.

Despite my belief in offset loading, it shouldn’t be misconstrued to say foundational (bilateral) strength isn’t very much a part of the recipe. Minimizing the likelihood of sustaining a soft tissue injury at a base level requires robust foundational strength. The same goes for pure speed and agility work—absolute sprinting is purely one of the best “soft tissue injury prevention” tools there is. My argument with the torque management is that conventional loading can become subject to diminishing returns for ligaments given the lack of torque demands, especially with more advanced/highly trained athletes.

One of the most effective things strength coaches can do for their athletes is improve their ability to tolerate torque—and offset loading requires an inherent tolerance for managing shearing stress. Share on XTrunk Stability and Lateral Chain Strength

The emphasis on anti-rotation and resisting lateral bending is another marquee benefit of offset loading for athletes. Much of what we see in sport is an expression of fighting and resisting external forces/torques as much as it is producing forces (e.g., breaking a tackle, driving in for a dunk against contact, throwing a pitch). I perceive the spine and core musculature as an engine that functions predominantly off a reciprocating, coiling action in which one side is always working in concert with the other (this applies anterior-to-posterior as well).

Very rarely—if ever—is external load applied evenly, or muscular activation distributed evenly between left and right sides of the body, or the trunk in this manner. This reciprocity requires the ability to demonstrate stability at certain areas of the trunk while producing movement at others. This illustrates another element of offset loading that could be favorable for athletic populations—slightly different muscular activation patterns between the right and left sides that are also slightly changing throughout the course of movement.

I would also argue there is an increased engagement from deep core muscles during offset loading in an effort to maintain spinal and positional stability as the athlete executes the movement. Our deep core muscles—namely the multifidi, internal obliques, quadratus lumborum (QL), and transverse abdominis—all play quintessential roles in providing intrinsic stability and force summation. Moreover, the deep fascia, which is also at play here, is where it has now been suggested that a large portion of mechanical force is transferred through the body to achieve motion. In my belief, core training is fundamental to sport performance, and offset loading is a premier way to emphasize these regions. But don’t take it just from me, as Stu McGill has famously said, “proximal stiffness for distal speed.”

Safety

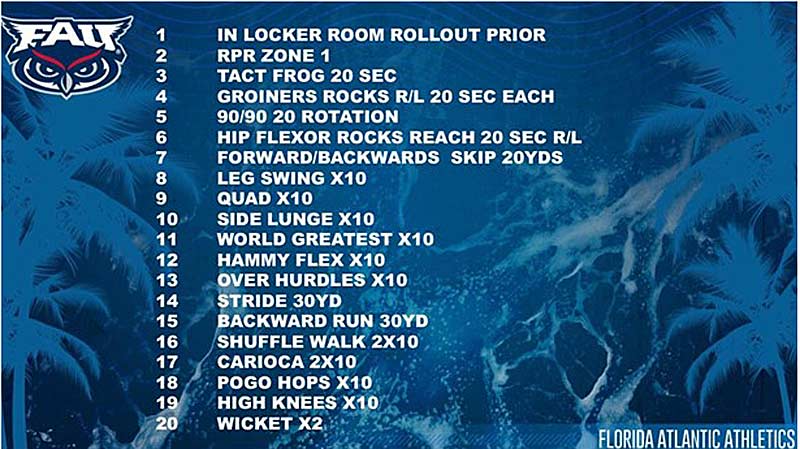

I can’t complete this article without highlighting some important risk and safety considerations, as this is an unorthodox style of training for most. It’s important that the athlete has developed a reasonably robust foundation with strength training, and equally important that the coach is familiar enough with this application to apply it safely and correctly. In addition, please see the graphic below:

Takeaway Points

Some final quick hitter points regarding offset loading for the sport performance population:

- Offset loading is a great option for increasing work capacity; athletes will be quick to recognize the mechanical and metabolic taxation that occurs during offset variations. I believe this is an ideal justification for early off-season work during GPP/reacclimating phases.

- Given the presence of injuries with tactical athletes, I can say confidently that offset loading is a great option once formal physical therapy/rehab has been completed. I believe the neuromuscular benefits (inter- and intramuscular properties) outlined above are the primary advantage here.

- Offset work can be advantageous for in-season training periods, as high CNS stimulation can be achieved without the demand for high absolute load. Augmenting CNS stimulation without a high magnitude of compressive forces is typically a win for most.

- Cognitive stimulation is significantly higher during offset loading, effectively precluding the athlete from being able to go into “autopilot.” In my opinion, driving cognition during training is woefully underappreciated and can have tremendous return for the athlete.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

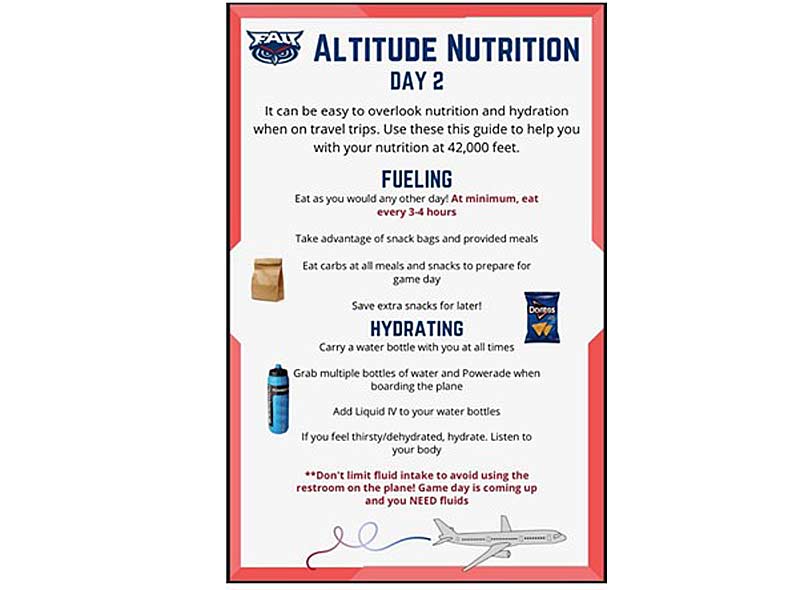

Autumn Bartlett joined the Florida Atlantic University staff in August 2021 as the football sports nutritionist. She graduated from the University of Florida in May 2020 with a dual degree in dietetics and nutrition science and completed her dietetic internship at Wellness Workdays.

Autumn Bartlett joined the Florida Atlantic University staff in August 2021 as the football sports nutritionist. She graduated from the University of Florida in May 2020 with a dual degree in dietetics and nutrition science and completed her dietetic internship at Wellness Workdays.  Adam Bennett joined Florida Atlantic University as an assistant athletic trainer in April 2015, working primarily with football. He then went to Minnesota for the 2016 season and returned to FAU in 2017 as the head athletic trainer for football. Before his first stint at FAU, Bennett interned with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers Athletic Training Department for a year, assisting with the prevention and rehabilitation of acute athletic injuries. He spent two years at the University of Southern Mississippi as a graduate assistant athletic trainer for football and women’s tennis while earning a master’s degree in sport management. Bennett got his B.S. in Athletic Training from Florida State while working with women’s soccer, football, baseball, and men’s basketball.

Adam Bennett joined Florida Atlantic University as an assistant athletic trainer in April 2015, working primarily with football. He then went to Minnesota for the 2016 season and returned to FAU in 2017 as the head athletic trainer for football. Before his first stint at FAU, Bennett interned with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers Athletic Training Department for a year, assisting with the prevention and rehabilitation of acute athletic injuries. He spent two years at the University of Southern Mississippi as a graduate assistant athletic trainer for football and women’s tennis while earning a master’s degree in sport management. Bennett got his B.S. in Athletic Training from Florida State while working with women’s soccer, football, baseball, and men’s basketball.