Coaching is the ultimate problem-solving activity. Each athlete is their own unique puzzle, but none is a standalone if the athlete is part of a team. Some puzzles are simple—the colors and patterns make it easy to see which pieces go together. Others are extremely complex, littered with shades of gray and chaotic patterns. To further add to this difficulty, we are dealing people, not stiff pieces of cardboard, so what happens when you feel you have pieces that should go together but they don’t quite fuse? What steps can you take to link physical output in training with physical performance in competition?

In the first part of this series, I outlined the new approach I used for our jumpers at Homewood-Flossmoor High School during the unique 2021 track and field season. Five drills were presented in detail, and links to additional drills addressed in previous articles were given.

Due to a shorter season length and a higher percentage of athletes being new to the jumping events, I decided to increase the frequency of these drills during “pre-practice” sessions—planning these two to three times per week with the hope of fast-tracking the learning curve of our athletes. The drills each athlete would complete were assigned individually, based primarily on what I found to be the most significant gaps in their technique. While it is the norm for athletes to improve upon their performances over the course of the season, I felt a portion of their improvement was due to what was being addressed by the drills—in other words, the specific part of a jump addressed by the drill was transferring to a full jump when it was performed.

If the appropriate drills are chosen for an athlete, improvements can occur, even if they are several generations removed from the actual event, says @HFJumps. Share on XI would like to reiterate that I feel the most valuable learning occurs when athletes improve in activities that are as few generations (if any) as possible removed from the actual event. However, if the appropriate drills are chosen for an athlete, improvements can occur, even if they are seven generations removed. In this article, I will lay out the drills chosen for a specific athlete: while the previous piece addressed the why, what, and how of those drills in terms of the entire jumps crew, this post will take a similar approach but narrow it down to a single athlete.

Background

The athlete in question—Jamar McMillian—was a senior in 2021. During his four years in our program, he always tested well in comparison to his peers:

-

- From 2018-2021, Jamar was always in the top 10 in our program (100+ athletes) in the countermovement jump (with arms). His best jump was 35.5 inches (via a Just Jump Mat).

- In 2020 and 2021, one of our fun “sprinter challenges” was to see who could obtain the highest peak power utilizing a 1080 Sprint. Jamar was almost always at the top of this competition.

- For the strength crowd, Jamar could deadlift more than three times his body weight. His isometric belt squat (crane scale) was almost twice as much as our other jumpers.

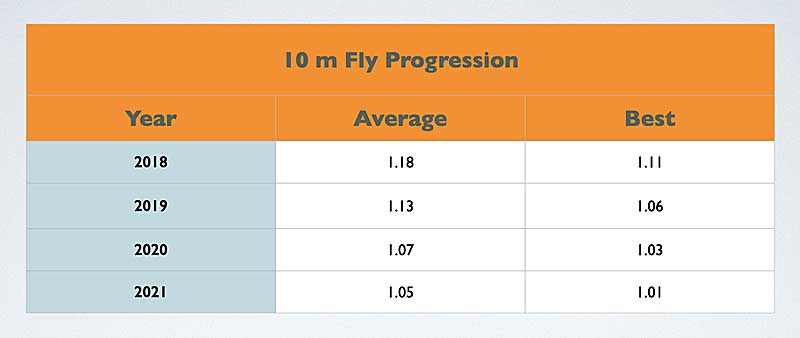

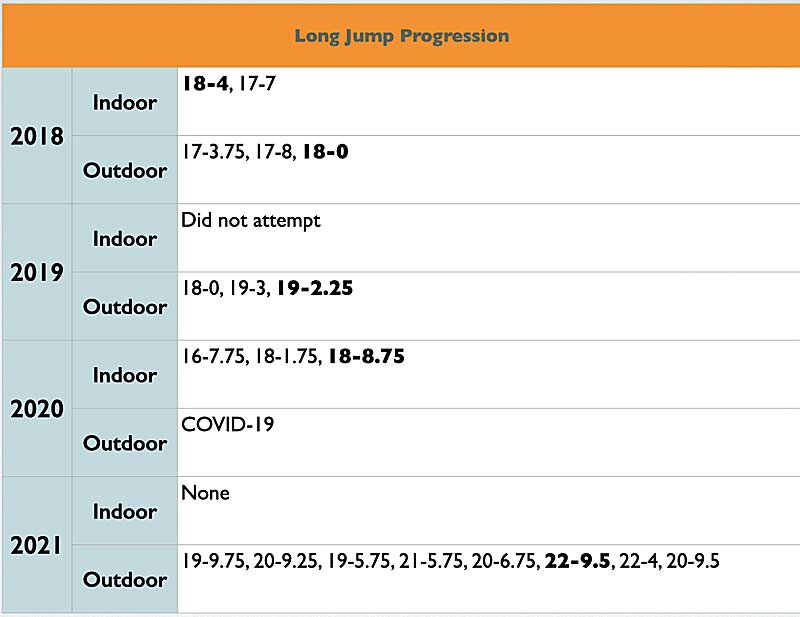

Although many of these numbers indicate an opportunity for elite performance at the high school level, I struggled to get Jamar’s ability to shine through in the jumping events. He was always a significant contributor, but his performances in competition did not match the outputs he had during testing. His bests of 1.11, 1.06, and 1.03 during his freshman through junior years correlate with an ability to jump well over 20 feet, which did not happen. Here is his four-year long jump progression:

-

- Jamar started off the 2021 season strong, with a 19-9.75 on a chilly day (April 24). While he continued to progress, I was not convinced that he could be a state qualifier in long jump (22-2) until May 15, when he jumped 21-5.75 in wet, mid-50° F conditions. He continued to participate in long and triple jump through our conference meet, as I was hopeful for a big PR in triple. Unfortunately, that did not transpire, but sometimes having it all means not having it all at once!

After conference, we decided not to pursue triple jump any further. Jamar’s individual physical plan was divided into two categories: gait correction and take-off correction. I will not discuss the items that were only specific to triple jump.

Gait Correction

Most of a jump attempt occurs on the runway, and if an athlete is not maximizing their ability through quality acceleration and upright mechanics, they will hit a false ceiling in the actual jump. Jamar was a tough case to crack. As seen in the video below, his feet rotate externally prior to ground contact.

Video 1. While slight external rotation is common in sprinters, in Jamar’s case it was definitely excessive. Chris Korfist used the analogy of his feet looking like oars turning over in water. This video was taken in the summer of 2020.

Before getting into specifics, I should point out that the gait correction strategies I use are highly influenced by Chris Korfist. Living in the Chicago area has allowed me to see him present more than 40 times, through Track Football Consortium, Reflexive Performance Reset, and ITCCCA.

I have also made numerous trips to his legendary basement: in 2020 (Jamar’s junior year), Chris became a part of our track and field staff, which made every day a learning experience. His ability to see issues in sprinting in real time and create correction measures is incredible.

Gait Correction #1: Ankle Rocker

During Jamar’s freshman and sophomore years, one item given to him for “homework” were ankle rocker exercises. Ankle rockers are where the shank rotates forward, resulting in dorsiflexion to help propel the body forward. Dr. Shawn Allen of The Gait Guys gives six compensation patterns for people who are unable to reach the needed amount of ankle rocker in this video. Jamar’s compensation was the second compensation addressed (external rotation of the foot).

The main exercises given to Jamar were ankle rocker shuffle and moonwalks, ankle rocker single leg squats, and ankle rocker jumps. Unfortunately, despite thousands of repetitions, this did not solve the issue of excessive external rotation of the foot prior to contact.

Gait Correction #2: Low Lunge Walks

Fast forward to Jamar’s junior year. Chris Korfist was now on our staff, and we began the season with A LOT of time devoted to low lunge walks. I have sung the praises of this exercise in multiple pieces, and I’m going to do it again. The benefit of this drill is that it takes the athlete through all four phases of rocker (heel, ankle, forefoot, toe) in gait. I truly believe this was the missing link for Jamar.

A common thought here would be: Was all the time spent on ankle rocker his first two seasons a waste? Could one just fast forward to this exercise? My assumption is that the ankle rocker work set the table for him being able to transfer the low lunge work to his running gait. So, it definitely was not a waste. That being said, if I could hop into a DeLorean with a flux capacitor, I would have Jamar perform ankle rocker exercises and low lunge walks concurrently.

If you watch an athlete perform the low lunge walk, the way they initiate and lose contact with the ground is the same way they do it in running gait. It tells the story before the story is told. Share on XAnother side note of the low lunge walk: If you watch an athlete perform the exercise, the way they initiate and lose contact with the ground is the same way they do it in running gait. It tells the story before the story is told. I am still waiting for a case where this is not true. This exercise has been an absolute game-changer in gait assessment and correction.

Gait Correction #3: Spring Ankle

Chris Korfist and Cal Dietz partnered to create the Triphasic Speed Training Manual, and a big part of it was what they termed the “spring ankle model.” The lower leg and foot are often overlooked in training, which is probably the strangest aspect of sport training since almost all locomotion is formed from the foot contacting the ground. The spring ankle model involves yielding isometrics, which can eventually progress into overcoming isometrics and other variations. The goal is to get the foot and ankle to be able to handle the forces generated from the whip of the hip. For Jamar, an additional benefit was to get his brain comfortable with the position of pressure on the ball of the big toe without excessive external rotation.

As a side note, I think overcoming isometrics are a training menu item that should be used with care due to their high intensity. However, I feel that the foot and ankle being able to handle load is so important that I would be comfortable using the spring-ankle exercises in an overcoming isometric style with most populations after time spent in the yielding style.

Gait Correction #4: Wickets with Arms Across the Chest

Many coaches use wickets to help improve running technique. A subset uses wickets with various arm positions. Another subset is able to dial in those variations based upon what the athlete presents in gait.

Because the arms act as a counterbalance, we eliminated them (arms across the chest) during wickets to present a greater challenge to the foot, says @HFJumps. Share on XJamar received a steady diet of “hugs” (arms across the chest) during wickets and other plyometric type activities. The reason he was given this specific variation was that by eliminating the arms, a greater challenge is presented to the foot. This is because the arms act as a counterbalance. When the athlete is at toe-off on the right foot, the left arm is back and the right arm is forward, making it easier for the right foot to roll through to the ball of the big toe. Taking away the counterbalance poses a more difficult task for where the issue lies.

Video 2. While different arm positions can be used for all athletes, knowing the why behind them makes them even more valuable.

Gait Correction #5: Exer-Genie with Diagonal Resistance

A by-product of Jamar’s excessive external rotation was periodic toe-offs where he would exit the ground off the fourth and fifth toes as opposed to the first and second. To assist with this “finishing ability” to go along with his improvement in not externally rotating the foot as much, we added exercises (sprints and bounding complexes) with diagonal resistance. This was stolen from Chris Meng via a Track-Football Consortium question and answer.

I really like this variation because it begins with a huge amount of lateral resistance on the left foot. As Jamar gets further away from the Exer-Genie, the lateral load becomes biased to sagittal. The enhanced load puts him into the pattern we are looking for, and then he is able to maintain that pattern in a more realistic setting.

Video 3. The exercise becomes more “realistic” the further he goes.

Gait Correction #6: 1080 Sprint Assistance

Seeing Chris Korfist present and working with him has caused me to view assisted sprints and jump complexes as more of a technical correction tool as opposed to just a training stimulus. Simply put, the assistance causes the body to move faster, which makes the brain feel threatened and have a desire to get the foot on the ground as soon and as safely as possible.

The result for Jamar?

Not enough time to externally rotate the foot prior to contact. This can be seen in the video below during a bound complex (it should be noted that I hypothesize this was even more effective because of all the foundational items mentioned above). Video 5 shows the same exercise with resistance. I included it because it shows that even when Jamar did not feel threatened, external rotation was small. For clarity, while watching videos 4 and 5, focus on the leg interacting with the ground.

Video 4. Assisted bound complex using the 1080 Sprint.

Video 5. Resisted bound complex using the 1080 Sprint.

By the end of the 2021 season, Jamar looked like a different runner—still room for improvement, of course, but much more efficient overall. Here is a video of him during the last few weeks of the season, running in socks. What sticks out to me compared to the 2020 video is his reactivity off the ground.

Video 6. Jamar from the front near the end of the 2021 season.

Take-Off Correction: Anti-Penultimate Box

The anti-penultimate box drill was discussed in the previous article, and it was one Jamar completed multiple times per week. Jamar’s biggest issue in the actual jumping part of long jump had always been too low of a take-off angle. Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to get quality and consistent jump video at a high school track competition; however, I think the videos below show his improvement in this regard.

Positive change is rarely due to one component, and there are certainly many factors which led to huge improvement for Jamar. Improved sprint speed and sprint technique and an increase in strength certainly played a big role. So did his flight style (free leg extending down instead of forward—a product of thousands of gallops and run-run-jumps). Furthermore, his landing improved because his flight improved because his take-off improved because he was more efficient on the runway. All this being said, I do think that the anti-penultimate box drill allowed him to dial in the feeling of what needed to happen to project himself into the air.

Video 7. Jamar long jumping in 2018.

Video 8: Jamar long jumping in 2021.

Additional Parts of the Equation

Reflexive Performance Reset (RPR): In the fall of 2019, I was invited to preview the beta version of RPR Level 3 Training. My partner was Neuqua Valley’s brilliant head coach, Mike Kennedy. When we were instructed on “the back 5,” Mike mentioned that he felt this method helped Neuqua’s jumpers’ performances skyrocket in 2018. I witnessed this incredible improvement firsthand as Neuqua’s jumpers performed incredibly well down the stretch and were a big reason why they edged us 52-48 in the 2018 state team competition.

Jamar had back issues throughout his career, and toward the end of this past season, they started to flare up again. I had a flashback in a dream of Mike telling me about “the back five,” and we started implementing those specific tests and reset techniques into Jamar’s plan. As so often is the case with RPR, Jamar felt a big difference (his phrase was “I feel like a new man”).

RPR is often a hot topic for debate in the social media world, but at the end of the day, I will take an athlete who feels “like a new man” on the runway over one who feels like an old man every day of the week and twice on Sunday. Whether it is correlation or causation that Jamar’s best jumps happened once we started this could be debated and ultimately never settled, but it certainly did not hurt!

Whether it is correlation or causation that Jamar’s best jumps happened once we started RPR could be debated and ultimately never settled, but it certainly did not hurt, says @HFJumps. Share on XIt would also be wrong of me to not include the fantastic job our athletic training staff (Brad Kleine and Danni Werner) did with Jamar. A basketball player can be 80% and still put up 30 points. In many cases, a track and field athlete at 80% might as well be at 2%. It often takes a village to help get an athlete to the finish line, and we are very fortunate to have a great village!

Maturity: One of the best parts about coaching track and field is that I am able to coach athletes for their entire high school track career. It is extremely rewarding to witness the growth athletes undergo, not only as athletes, but even more so as people. Jamar was always a dedicated athlete. When given specific “homework,” I could trust that he would do it. When given a task to complete during practice that I may not have been able to oversee because I had to work with high jumpers, I was always confident that Jamar would take care of business.

Jamar’s dedication to his craft allowed me to navigate what was and was not working with his training. The truth is, during his four years, I had more misses than makes in his programming, but because I could trust his adherence to the program, it allowed me to identify the misses earlier and make adjustments. Jamar was the driving force behind the interventions resulting in improvement in performance, and all credit should be directed toward him.

A by-product of Jamar’s dedication was the disappointment that came along with not achieving desired results. During Jamar’s first three seasons, if his first event did not go well, it was a significant challenge for him to put it behind him. This often snowballed into him struggling in the other events in which he competed that day. This was also seen during a series of jumps: If his first two jumps did not go well, it was probable that the remaining jumps would not go well either.

In 2021, there were multiple times where Jamar showcased the ability to put what he deemed a bad attempt or subpar performance in the rearview mirror and not let it impact what he did moving forward. While I had many conversations with him during the tough times, the most credit in this area should be given to his mother, who was a constant source of support. While the incredible improvement in long jump was a pleasure to watch, Jamar’s improvement in being able to effectively deal with adversity was, without question, my favorite part of the 2021 season.

Jamar does not know this, but during our sectional competition, he was well short of the state qualifying standard after his first two attempts. I texted our coaching staff and said, “not looking good for Jamar.” In previous years, Jamar would have let the first two attempts send him into a downward spiral; however, Jamar was able to keep his poise and exceed the qualifying mark on his third attempt.

I was never happier to eat my words than the ones I had sent in that text to our coaching staff!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF