It’s extremely rare that I’ll make a claim like this one skill can help ALL athletes improve because just saying it out loud sounds like clickbait. But here we are…

I’ll get right to the point. Juggling. Yes, juggling is the one skill that all athletes can benefit from.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to the methods with which we train our athletes. Athletes are too different for there to be one best way to do things. This is why I said it’s very rare for me to claim that this one thing can help all athletes. But in the case of juggling, it is actually one of the exceptions.

Before we dive deep into the key benefits—hand-eye coordination, brain development, sport specificity, and motor learning—we must look at the big picture from a 30,000-foot view.

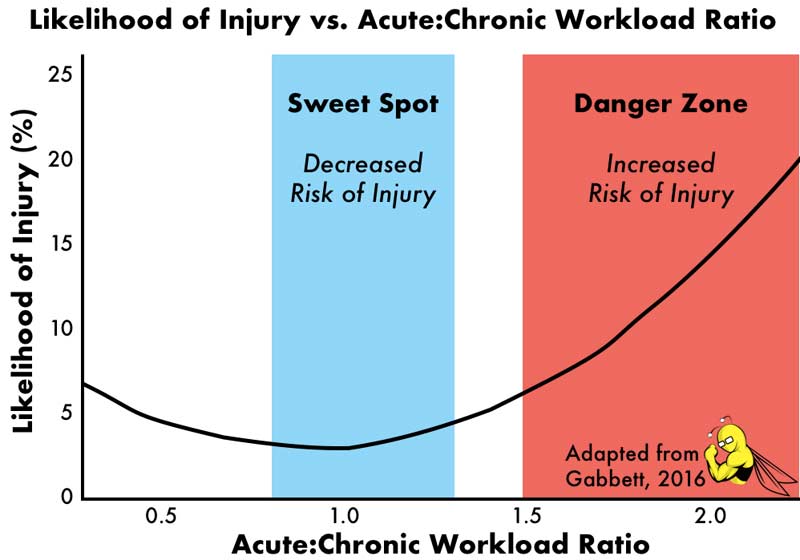

It’s universally accepted that the #1 job of a strength coach is to do NO harm. So, our job is to implement whatever strategies we feel are appropriate to elicit a training response with no harm done to our athletes. This means we must constantly evaluate the risk versus reward of our program.

Juggling is, by far, one of the most harmless training modalities I’ve ever come across, with a significant upside and potential for positive outcomes, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XJuggling is, by far, one of the most harmless training modalities I’ve ever come across, with a significant upside and potential for positive outcomes. This is why I feel so confident in saying that, literally, all athletes can benefit from learning this task.

How It All Began

This all started in the gym when one of my athletes randomly started juggling between his sets of deadlifts. I thought to myself, “That’s actually a really good idea.”

In the past, I have played around with vestibular and cognitive challenges as a rest period between sets:

One of my favorites was to have the athlete close their eyes, and then throw them two different balls and shout out the name of a color. The challenge was to open their eyes when they heard the color, track the ball, and catch it. I found that these small games had multifaceted benefits.

First, you obviously get the visual and cognitive benefits. But you also get an excellent fatigue monitoring system built into the games. When athletes are more fatigued, their vestibular system won’t be as sharp. They often fumble or drop the ball. As they recover from the set, they start to improve their performance. This indicates that the system is restored and ready for the next set.

Juggling in this context never crossed my mind. Why? Because I couldn’t juggle and had never even attempted to. But something about how easy my athlete made it look that day and how much fun he was having doing it made me want to try.

I tried. And I sucked.

When I try new things and suck at them, you can basically guarantee that I will become obsessed with whatever that thing is until I figure it out. So, I did.

I learned how to juggle, practiced, and eventually got pretty good. And then, my wheels started to turn with ideas on how juggling could be beneficial given some general background of the known benefits. Here are four of those benefits.

1. Hand-Eye Coordination

The most apparent benefit of juggling is the improvement in hand-eye coordination. This also has the most significant impact on sports performance. You’d have to look far to find a sport where improving hand-eye coordination wouldn’t be a benefit.

The most apparent benefit of juggling is the improvement in hand-eye coordination. This also has the most significant impact on sports performance, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XAlso, beyond sports, improving hand-eye coordination is never a bad idea. This could help with daily tasks such as driving, multitasking, and even using the handheld devices that are such a big part of our society today.

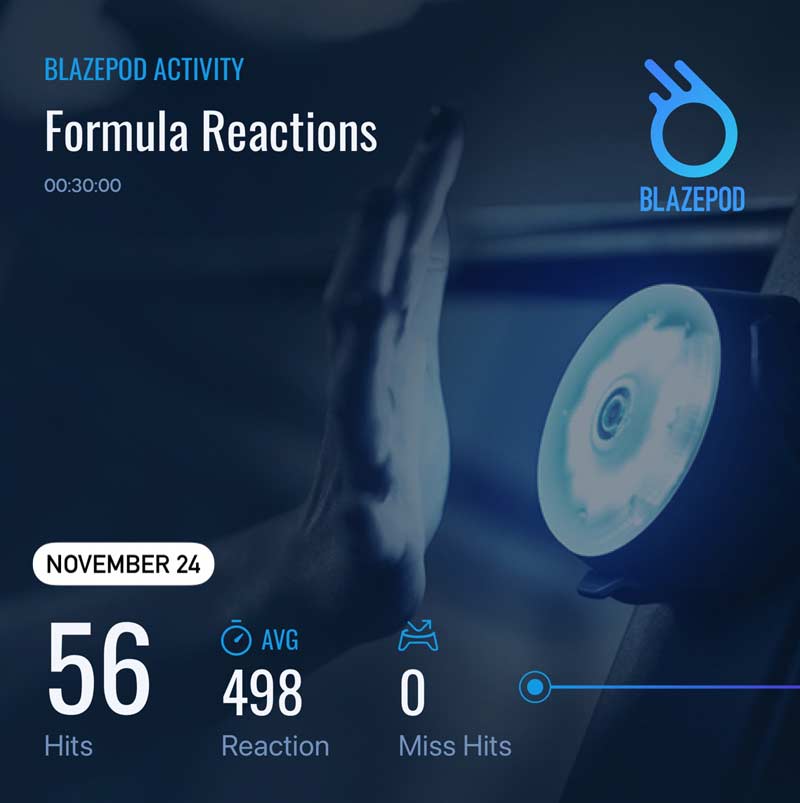

The first day I tried to juggle and failed, I decided to make myself into a case study. I used the Blaze Pod light reaction system to test my hand-eye coordination. This was my report on that day.

I practiced juggling for 10 minutes a day for one month and then retested. Not only did my juggling skills improve significantly, but so did my hand-eye coordination. I changed nothing else about my life or my training than the fact that I introduced juggling.

This wasn’t performed in a lab, nor is it a published research project, but it tells me pretty clearly that juggling has positive effects on hand-eye coordination.

And, just to make sure it wasn’t all newbie gains, I went ahead and went one more month and did another test. Sure enough, I kept improving. This time, my score improved to 56 hits and an average reaction time of .498 seconds.

In just 10 minutes a day, accumulating absolute zero fatigue, soreness, or injury risk, I was able to improve a universally sport-specific attribute. As discussed in the introduction, if you don’t have 10 minutes to spare, you can simply work it in between sets or throughout the day.

In just 10 minutes a day, accumulating absolute zero fatigue, soreness, or injury risk, I was able to improve a universally sport-specific attribute, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XFurthermore, even though I am a washed-up coach now, I still play basketball at a pretty high level 1–2 times per week with a solid group of ex-college and pro players. Anecdotally, I have noticed myself making much better reads and passes with my nondominant hand—something that truly stands out because I had been dealing with a broken finger on that hand.

This gave me the ultimate confidence to implement this with all my athletes, regardless of sport or age. And they’re all seeing similar results. Many of the skill development specialists in our facility—such as wide receiver coaches and hitting instructors—are also implementing juggling and noticing the same improvements with their clients.

2. Brain Development

The deeper science and research on juggling and its effects on brain development are genuinely fascinating. My case study above was me just being curious and operating on a hunch—once I realized there were positive results, I started to dig up actual research in this realm and was really blown away by the findings.

Many studies on brain development revolve around gray matter, which has proven links to our memory and focus. Gray matter is made of neuronal cell bodies and conducts and processes information to send to other body areas.

Although gray matter is thought to be fully formed by our twenties, we can still enhance it after that age, as proven by a brain study performed in 2008.1 Researchers tested 20 participants with an average age of 26.5 years old to investigate the nervous system’s adaptive behavior to learning a new skill.

That skill? Juggling.

The researchers were able to confirm training-induced gray matter changes in the brain. They found a significant increase in brain gray matter during the exercise and in the short term after the study. There was no conclusive data for what happens to this grey matter after three months or after the skill is forgotten. Nonetheless, participants grew their brain’s gray matter, which unlocks a ton of potential for other motor learning tasks.

Researchers found a significant increase in participants’ brain gray matter during juggling and in the short term after the study, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XAmazing right?

What’s even more impressive is that researchers in a different study found the first-ever evidence of training-related changes of white matter in the human brain just a year later.2 White matter constitutes the other “matter” of our brain. Made of axons and myelin, white matter is found in the much deeper tissues of the brain compared to gray matter. White matter interprets sensory information and has not been studied at the level that gray matter has.

In this study, juggling was again used as the training methodology. Researchers provided juggling materials to 24 participants, who were to practice for 30 minutes per day, and they had a control group of 24 participants who did not juggle. Both groups had MRI scans before and after the experiment.

After six weeks, the non-juggling group did not show any changes in the brain’s white matter. However, the juggling group showed growth in the white matter area of the brain, especially in areas related to vision and movement. What’s also interesting is that even the jugglers who had not yet mastered the task still saw the same benefits simply from trying to learn the new task.

I am no brain specialist by any means. Still, the positive changes that the actual brain experts are seeing in their studies—and the fact that they’re using juggling as a means of training—should speak volumes to just how impactful juggling can be for our brain development at any age.

3. No Limitations

Another great benefit of juggling with our athletes is that there are truly none of the limitations that exist in other aspects of sport. Height doesn’t matter. Speed doesn’t matter. Experience in sports doesn’t matter. It’s only limited by the time you put into it. A prime example is Casey Boehmer, a world-renowned juggler who only has one arm.

I really like this aspect of juggling because it’s an excellent tool for teaching confidence to athletes who may need some small victories of their own. For example, you could teach a below-average athlete who lacks confidence to juggle. They can learn the skill, outdo the “better” athletes in the group, and immediately gain confidence from that small personal victory. That could lead to more and more gains in other aspects of their game and training. Confidence has a unique snowball effect.

Because juggling has none of the limitations that exist in other aspects of sport, it’s an excellent tool for teaching confidence to athletes who may need some small victories of their own. Share on XAlthough juggling is not a sport skill that appears in any sport, it enhances the qualities we use in several sports. This is the same as juggling with everything but your hands in the soccer world. All great soccer players master juggling the ball; it showcases rhythm, coordination, first touch, and body control. But it will never happen in a game, and that’s okay. It builds qualities that will occur in a game.

The same goes for dribbling tricks in basketball. Athletes don’t practice complicated trick dribbling routines to use the exact routine in a game but to challenge their hand-eye coordination, balance, rhythm, and ball control, so the simple moves they use in-game are maximally efficient.

Perhaps the example that drives the point home the most is a boxer using a speed bag. Have you ever seen Mike Tyson punch another human like he punches a speed bag? No, never. Tiny punches with the back of your fist aren’t going to knock anyone out, but the speed bag builds up the hand-eye coordination, hand speed, and upper body endurance that are crucial for fighters.

As coaches, we need to understand that not all training will look precisely like the sport. But as long as the result of the training will enhance our sports performance while doing no harm to the athlete, the juice is worth the squeeze.

4. Rhythm and Coordination

Finally, the rhythm and coordination that you experience with juggling can greatly carry over to other training modalities or sports. One of the keys to juggling that I’ve had success with is making it a whole-body motion. I find that when I get my knees and ankles bouncing with the rhythm of my catches and throws, I feel the most locked-in.

It’s no different than a basketball player using rhythm to change their pace on a drive to the basket or a marathon runner finding a good pace and rhythm during their run. So much of athleticism is based highly on rhythm and coordination, and this is a really simple way athletes can enhance that quality.

All the things covered so far—hand-eye coordination, brain development, confidence, coordination, and rhythm—are universally sport-specific.

Juggling will not make you better at your sport. The benefits that athletes achieve through juggling can help enhance their ability to perform the skill of their sport at a higher level.

This could lead to improved passing, ball handling, or defensive outputs for basketball. For a wide receiver in football, this could lead to better ball tracking and catching ability because that is precisely what juggling is—it’s just a different ball. For baseball/softball, we could see an improvement in hitting and fielding.

As I said, it would be challenging to try to name a sport where these neural improvements aren’t worth 10–30 minutes a day of non-fatiguing training like juggling.

Lastly, tennis balls and lacrosse balls have become very common in the sports performance world as reactionary tools. These are tools we all have lying around the gym.

A simple drill I love is the ball-drop exercise, where a coach drops the ball to start the drill, and an athlete sprints to catch the ball to complete the movement. Or the coach drops two balls and calls out a command for which one to catch. These are great reaction, speed, and agility drills. While the balls are out, why not juggle them to recover between sets?

These drills work all aspects of the system and genuinely get the most from our time with the athlete.

How to Juggle

All these benefits are fantastic, but the question remains…how the heck do you juggle?

I am by no means an expert juggler or juggling instructor, but I managed to teach myself in just a few days. At first, it was a rough learning curve, but I eventually got to a point where I could manage to do some tricks and juggle for long durations with no drops. Below is how I learned and how I’ve been teaching my athletes, broken down into very simple steps.

Tip: Start with a solid, moderately weighted ball about palm size like a baseball, bean bag, or hacky sack. I don’t recommend using tennis balls to start.

Step 1: Two-Throw Exchange

Video 1. Step 1 is what I call a two-throw exchange. This will involve two throws and a controlled catch, repeated over and over.

Start with two balls in your dominant hand and one ball in the other. With your dominant hand, toss one ball into the air. While that ball is airborne, toss the ball in the nondominant hand to free up that hand to catch the first ball thrown. Catch the first ball in the nondominant hand and then the second in the dominant hand. You should end up right back at square one, with two balls in one hand and one in the other.

This will build your general timing and get the pattern down for eventually juggling. Throw, throw, catch, catch, and then reset. Do not rush between reps. Treat each one as a single rep to get a feel for how hard and high you need to throw the balls.

Step 2: Three-Throw Exchange

Video 2. Building onto our two-throw exchange, you can progress into a three-throw exchange. This starts the same as step 1, but you’ll add an extra throw and then again end with a controlled catch.

So, you’ll throw the dominant hand, nondominant, then dominant hand again and catch the balls. Now, you should end up with two balls in the nondominant hand and one in the dominant hand. If you want, you can start the next rep from this scenario, flipped from how you started, or reset all the balls and go again. Personal preference.

Step 2 is a complete cycle of ball movement and the exact movement you’ll need to master to move on to step 3.

Step 3: Time Goals

Video 3. You repeat the three-throw exchange in this step but never catch the balls. Just keep the cycle going.

A simple rule that helped me put it all together is that you have to throw one to catch one. There will always be a ball in the air, and to catch it, you must toss one up to make room in that hand. If you just adhere to this simple rule, it will all come together for you in step 3.

The purpose of step 3 is to achieve time goals. I started with 15 seconds with no drops. That’s a major milestone. After that, 30 seconds with no drops is the next milestone. These are not easy tasks.

It’s frustrating. I once practiced for 30 minutes straight without getting a 30-second unbroken streak. But the reps add up, and one day it will click for the athlete.

Step 4: Space Goals

The final step is adding a space goal or a space constraint. Sometimes, you have to chase the balls around to keep them in flight, especially when trying to reach a time goal. This is more survival mode than juggling.

Adding a space constraint forces the juggler to focus on ball control and body awareness. The smaller the space, the harder it is.

You can start with a designated area using tape or cones to provide out-of-bounds lines, then move to tighter spaces like standing inside a tractor tire or hula hoop.

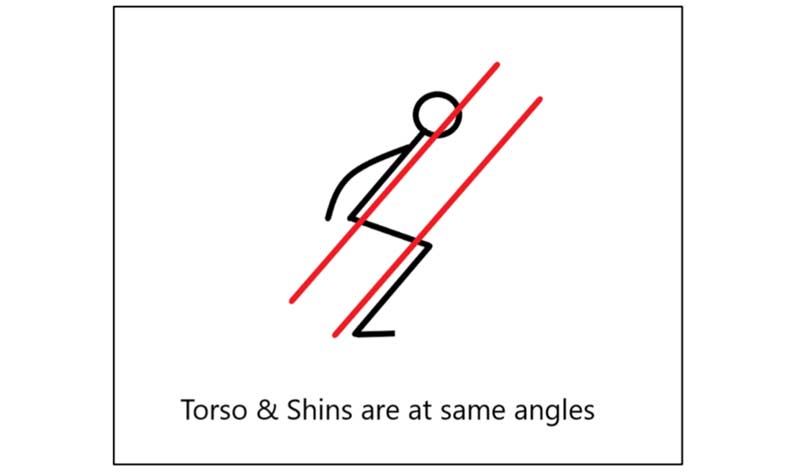

I’ve even been experimenting with long-duration isometric holds while juggling, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XI’ve even been experimenting with long-duration isometric holds while juggling. Holding a split squat or wall sit or balancing on one leg is a different ballgame when you’re also trying to successfully juggle for minutes at a time.

Bringing It to Your Facility

I realize that this article may not be for everyone—we all coach in different environments and have our own situational challenges in our setting.

With that said, I highly recommend introducing juggling, if at all possible. The benefits we’ve seen in a short time have been extremely impressive. Not to mention, it’s such a fun activity—even if you’re not good, it’s oddly satisfying just to continue to try.

We see a lot of circus tricks these days from trainers on social media, but this circus trick is actually a beneficial one.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Driemeyer J, Boyke J, Gaser C, Büchel C, and May A. “Changes in Gray Matter Induced by Learning—Revisited.” PLoS ONE. 2008;3(7):e2669.

2. Scholz J, Klein M, Behrens TEJ, and Johansen-Berg H. “Training induces changes in white-matter architecture.” Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12:1370–1371.