Elmhurst University embodies tradition. Historic brick buildings dating as far back as the Reconstruction era, refined tree-lined walkways, and nostalgic classrooms with old school ceiling panel lights and periodic tables posted on the walls. In this rarefied air, the December 2024 running of the Track Football Consortium teetered on a fulcrum of convention and disruption.

Fitting—that’s also the pivot point of sport.

Well-drilled technical skills and tactical pattern recognition veering into bursts of dynamic how you like me now creativity. Discipline, preparation, and standards offset by the untamed will to throw caution to the wind and let it effing rip.

How do you know what to do in the moment? How do you know what impact that decision will make? When should you stay conservative and “fall to the level of your systems” and when do you burn the boats and go with your gut?

How do you know what impact your decisions will make? When should you stay conservative and *fall to the level of your systems* and when do you burn the boats and go with your gut? asks @CoachsVision. Share on XCoaching is problem-solving and Problem #1 for those in attendance at TFC 2024 was choosing which speakers to see in the first place, with 18 presentations spread across six time blocks in three separate buildings. For me? Start with a well-thought-out plan and be prepared to audible.

I don’t mind admitting: very little went according to plan. And, like every other coach in attendance, due to the realities of time and space, I automatically missed twice as much as I saw… yet here I am, compiling takeaways and preparing to act based on a busted scheme and what is, from the outset, incomplete information.

Which may in fact be the meaning of it all.

Question #1. Are You Capable of Managing Uncertainty? Are You Sure?

“When you run, you do anything you can to seek a horizon.”

First—Orientation. Chris Korfist identifies this as the brain’s primal directive. In the chaos of an explosive sports action—before setting off an entire chain of events—you begin by creating order. Locate a horizon, then seek stability.

Korfist says that the fastest accelerators harness speed itself to create that stability—speed can be an organizing principle. Korfist now focuses intently on that moment when the foot first hits the ground, with an athlete’s ability to be the fastest in their first 3 steps a crucial differentiating skill (“how can we get more players to 6.0 m/s by step three?”). For everyone else, though, finding stability is what then leads to the next propulsive step forward.

Video 1. TFC co-founder Chris Korfist: “You go to where you’re strong.”

Les Spellman elaborated on this phenomenon in coaching terms—as a young coach, his first orienting step was an obsessive quest to learn everything about drills, everything about progressions, everything about applying technologies like GPS and 1080 Motion.

You go to where you’re strong.

Over time, Spellman has come to view his role as a coach more through the lens of his ability to solve problems, make better decisions, and manage uncertainty in order to create positive outcomes. He’s asking different questions. From a bold YES in response to being asked “can you make me faster?”…Spellman now asks questions that are far more open-ended.

Do I know what I need to know to help you play your sport better?

How can I help you stay healthy enough to perform consistently at a high level?

Over time, @les7spellman has come to view his role as a coach more through the lens of his ability to solve problems, make better decisions, and manage uncertainty in order to create positive outcomes. Share on XVideo 2. Les Spellman on the pyramid from data collection to wisdom.

Those complex questions require more than a knowledge of shin angles and plyo progressions and force-velocity curves. They require accurately identifying problems and dealing with information that will, by definition, be incomplete and filtered through biases. Those questions require a paradoxical willingness to boldly master uncertainty.

Importantly, though, Spellman’s pyramid is built from a base of data and information gathering, those first steps he pursued so diligently as a younger coach—can knowledge and wisdom exist without that early foundation? Can you truly be creative on the field and solve movement problems without laying those essential bricks of movement competency, speed, power, competitive will, and game understanding?

What is your mindset when complications arise? What strength do you fall back on to orient yourself? Is that position of strength helpful in that chaotic moment…or is that position now an anchor holding you back?

Video 3. Dan Casey paraphrases Bill Walsh: “Be bold. Remove the fear of change from your mind.”

Using Bill Walsh as his North Star, Dan Casey emphasized the importance of the hall-of-fame coach’s mantra to look for opportunity rather than ordeal when faced with a challenge. LFG or woe is me—you choose. Not only is that mindset crucial for problem-solving in general, but the very nature of addressing unexpected difficulties allows for unpredictable solutions—for unique opportunities—you would never have considered had everything continued along a smooth and steady course.

“Don’t complain about what you don’t have,” Casey said. “Identify what you do have and work with it.”

Question #2. Does Our Preparation Equip Us for Game-Defining Moments?

Absolutely! …right? I mean, we’re on the field, we’re in the weight room, we’re clocking sweat equity, we’re doing work.

Guided by…? Habit? Tradition? Limitations? Convenience? Killing time?

Brad Dixon dove into what was needed to not just develop faster and more explosive athletes, but which types of preparation would best equip his football players for the demands of the sport. In a game of collisions, can you manage that impact—that sudden and uncertain force—without give?

Dixon shared demos of “plate catches” learned from Dan Fichter, with players catching a falling bumper plate to learn how to manage gravity and load without folding; he shared altitude drops into different stances, preparing athletes for those game-defining moments of contact.

Video 4. “They have a 405lb squat but they can’t get out of their football stance”—Brad Dixon on athletes who can’t deal with slack in a system.

Video 5. Drops and catches to prepare the upper and lower body for game-relevant contact.

Early on in his Day 2 presentation, Spellman asked that very question—does our preparation equip us for game-defining moments? The unrelenting consequence of scaling up the pyramid towards wisdom is that instead of yes/no absolutes, questions tend to lead to follow-up questions and the next shifting unknown.

Does speed help us win games? Good question. What, then, is speed? Good question.

Video 6. Les Spellman on how he has come to redefine speed as it relates to team sports and the game-defining moment of creating separation and space.

Creating separation, closing space, attacking a gap…where do the first bricks in those foundations come from? Preparing for the chaos of sport does not mean to coach chaotically.

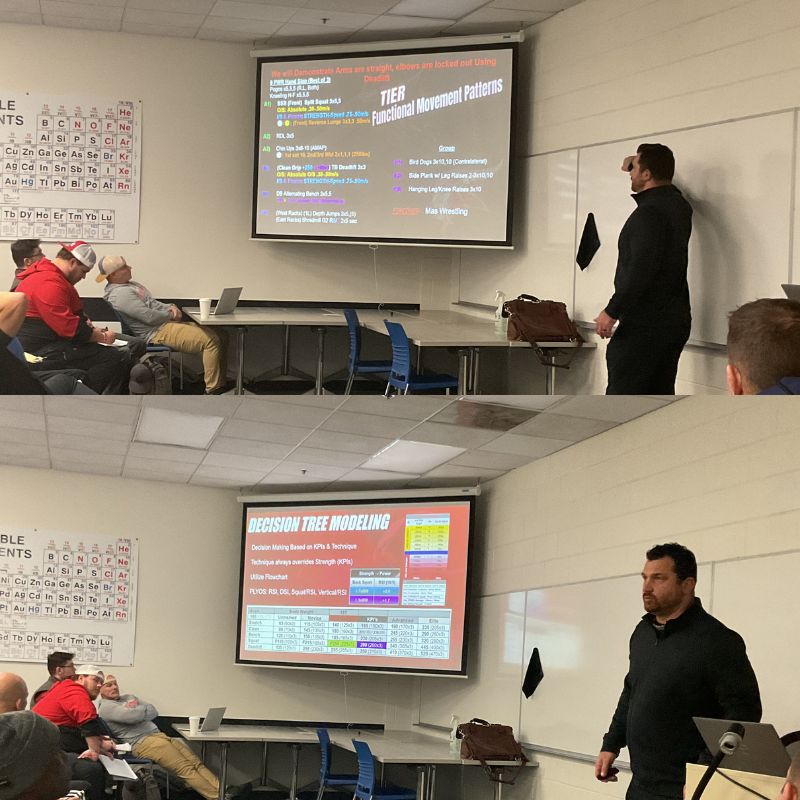

With upwards of 1200 student-athletes coming through his high school program, Adam Vogel broke down decision-tree modeling and the tiers, phases, and systems he has in place to develop stronger, faster, more explosive, and more resilient kids who participate in school and after school, in-season and out-of-season, across an entire range of sports and developmental levels, with total numbers that could create a sense of drowning in overwhelm.

Within all of the structures and systems Vogel uses to give shape to what could otherwise be a chaotic influx of student-athletes, he still locates opportunities to individualize where he can by identifying the assets he has and working with them. That, and refusing to stay rooted in anything that’s not working.

“Find people that make you think differently,” Vogel advises.

Question #3. What Happens When the Roots of Your Coaching Tree Tangle with the Half-Life of Knowledge?

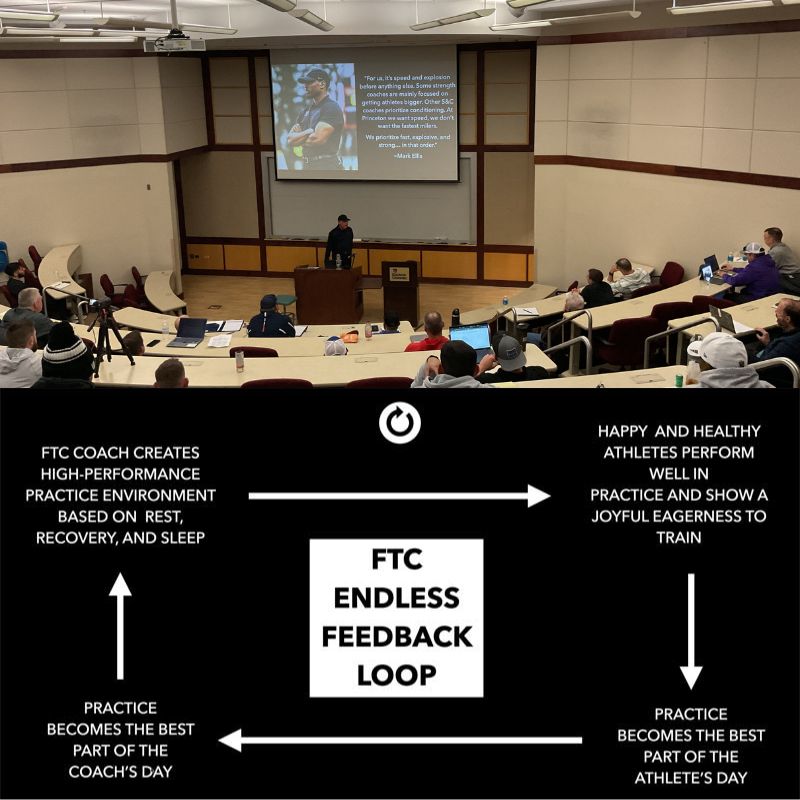

The Elmhurst campus wasn’t the lone bastion of tradition at the conference. Now over a dozen years in—boasting its largest ever in-person audience—TFC too has become a tradition, with recurring norms and self-referential cycles. Multiple speakers posted slides referring the “FTC Endless Feedback Loop”—these loops, these patterns, these recursions create stability in complex systems.

Past attendees have become current speakers, delivering presentations that hinge on their own applications of TFC learnings; meanwhile, TFC’s original rebel talents quote and confirm each other’s work in ways that are now more an act of homage than revolution.

During one break between presentations, Tony Holler talked about how the next generation of Feed The Cats track coaches are better than he was, in no small part because they were early adopters and didn’t waste any steps slogging through the same years of old-school tradition.

Speed can be an organizing principle.

Video 7. The branches of Holler’s coaching and family trees intertwine, with his sons Alec and Quinn presenting on coaching hurdle technique and training key technical skills for the 4x100m relay including lane ownership and the Bang Step.

Oh, the kids these days.

Spellman touched a common nerve in his Day 2 presentation, getting nods of affirmation in-person and across social media when he talked about deciding to pause his internship program because all the younger coaches who applied came in so sure they knew everything already.

Video 8. “You go from high confidence early on…then get smacked in the mouth.”

You go to where you’re strong.

By voicing that common brush with personifications of the Dunning-Krueger effect, Spellman also unintentionally drew the lines of a new old-guard—those rebel talents now tasked with the challenge of shepherding in the next generation of coaches.

Closed systems collapse in on themselves—so, how do you branch out?

Dan Casey emphasized that well-beyond Bill Walsh’s innovations with the West Coast Offense and personal accolades as a coach, his greatest legacy could be found in the fulness of his coaching tree and the manner in which he devoted himself to helping his coordinators and assistants thrive and achieve greater success outside his program.

Video 9. Casey reflects on his personal evolution in terms of communicating with his assistants: “I thought I was holding everyone to a high standard, but what I was really doing was I was starting to get into a dangerous zone of criticizing people in almost a personal way.”

These coaching trees are filled with believers, and Spellman pointed out how our biases dictate the content of what we learn: “Once you develop a belief, you find what supports it.”

First—Orientation. You go to where you’re strong.

There is, however, a pivot point—Spellman discussed “the Half-Life of Knowledge,” asking “how long does it take for 50% of something to be proven untrue?” That tipping point, where what once appeared stable instead collapses under its weight.

“Respect the past without clinging to it,” Casey said, while being forthright about how he can look back at things he published with high confidence 7-8 years ago…but which he now has the wisdom to recognize as being entirely wrong.

What will be the half-life of the knowledge shared in Chicago? Chris Korfist admitted to committing FTC heresy with his prioritization of acceleration over max velocity, Spellman focused on game speed over pure linear mph, and the next branches of the TFC coaching tree will question, adapt, and in time reject some of what was once accepted as true.

Before that inevitable disruption, Tyler Germain closed out TFC 2024 with a presentation rooted in what he’d initially learned by attending TFC in 2019, prior to taking his first head coaching position. With Tony Holler nodding support from the front row, mentor and student, Germain touched on the essential source of community among track coaches: “There’s no defense in track and field. My success is not dependent on your failure.”

With @pntrack nodding support, mentor and student, @TrackCoachTG touched on the essential source of community among track coaches: *There’s no defense in track and field. My success is not dependent on your failure.* Share on XVideo 10. “It was driving me crazy, but I didn’t really know why until I met Tony and I was like, oh I get it now, this is why kids don’t want to come out for track.”

That unguardedness characterized Germain’s presentation—and the broader sense of community among TFC participants. Germain’s distillation of the FTC Endless Feedback Loop is to “keep training fun, relevant, and brief” and build momentum by prioritizing speed. Doing so, in just a handful of years, he has doubled the size of his school’s track program from ~70 to over 140 athletes (and knocked off a perennial state champion in the process).

Speed can be an organizing principle.

From a clinic in Chicago in 2019, five years later the Butterfly Effect is that a high school track program in Michigan has doubled in size. Unpredictable. Come 2029? “Chaos” was defined by Edward Lorenz as when the present determines the future, but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future. The future, then, will be determined by the management of that uncertainty.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF