Creating a test battery can be difficult for many sports performance professionals, especially those with limited staff, equipment, space, and budget. However, it is our job as professionals (whether you are a strength and conditioning coach, athletic trainer, or sport coach) to provide the most appropriate test battery to assess our athletes as best we can.

Picking assessments can be challenging since many field-based sports contain so many dynamic performance attributes—it can be overwhelming when deciding where to begin. Working at the high school level and with a small budget, I do not have access to expensive equipment. This article will be for those coaches working with the bare minimum and making the best of it. I can confidently say the ideas provided will benefit team field sports.

Technology Is Your Friend

I originally wrote this article with the idea that these tests I mention will only require a field, tape measure, and a stopwatch; however, I have changed my mind, as there is plenty of inexpensive technology that coaches should invest in. So maybe, on second thought, we ditch those stopwatches and invest in technology.

The amount of technology that can fit into a cell phone or mobile device is astonishing. A coach can nearly have a mini sports lab at their fingertips. Not having a reliable or objective way to time or record linear sprints, vertical jumping, horizontal jumping, or change of direction tests is unacceptable at this point in time.

So maybe, on second thought, we ditch those stopwatches and invest in technology, says @KCPerformance_. Share on XFor linear speed tests, I personally use a Freelap timing system. I purchased it myself because I wanted something reliable. If you are currently using a stopwatch or your smartphone to time linear speed, consider making an investment in a Freelap timing system. It will save you a lot of time and you can time a lot of athletes very smoothly.

If you do not have a few hundred dollars in your budget to afford a Freelap timing system, there are companies who have created affordable apps that can be used to record the time of linear sprints. There are a few other apps I use for other tests which I will address.

Test Selection

In order to decide what tests to use, the administrator of the test needs to break down the biomechanical and metabolic demands of the sport. Make sure the tests that are selected are valid and reliable. Each test should be able to assess the correct ability, and each test should be able to retest accurately over and over again. The selected tests should be administered several times during the year, which is why it is vital to select tests with high reliability.

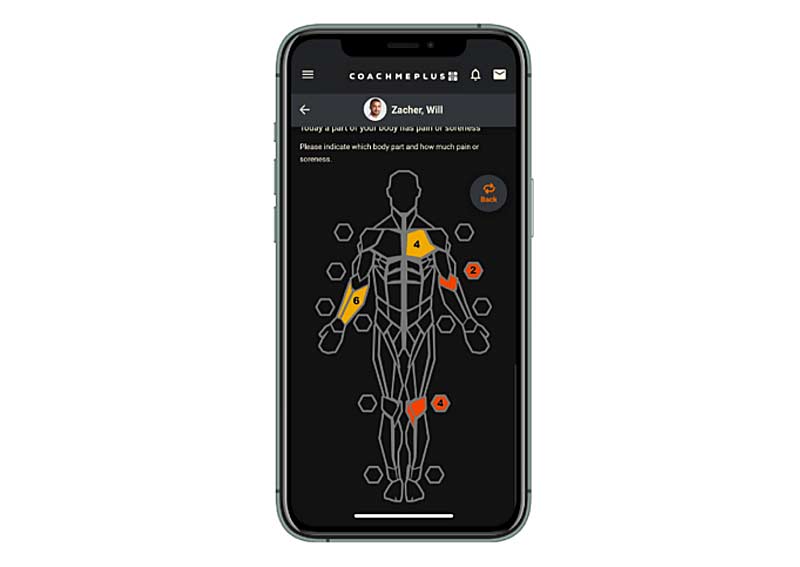

Environmental factors play a role as well: testing surface, temperature, and the time of day all affect results. Tests are not just for identifying talent or fitness but are also ways to gauge athlete readiness to return to play after sustaining an injury. Reduce the guessing and subjectivity of return to play assessments and use these tests to properly evaluate the recovery of an athlete.

Every sport is different in some way, so make sure you customize your test battery to cater to the demands of the sport, says @KCPerformance_. Share on XIf they are pain-free but their testing is significantly worse than before the injury, they might not be ready—a harsh reality for the athlete and coaching staff, but it is the safe and appropriate decision. Nothing kills an athlete’s confidence and motivation like back-to-back injuries.

In the high school setting, tryouts last about a week. In order to respect the available time of the coaching staff to evaluate specific skills of the athletes, it is best to perform the test battery in a single day. Since many of the tests may be assessing completely different physical qualities, it is important to perform each test in a certain order. That order being:

-

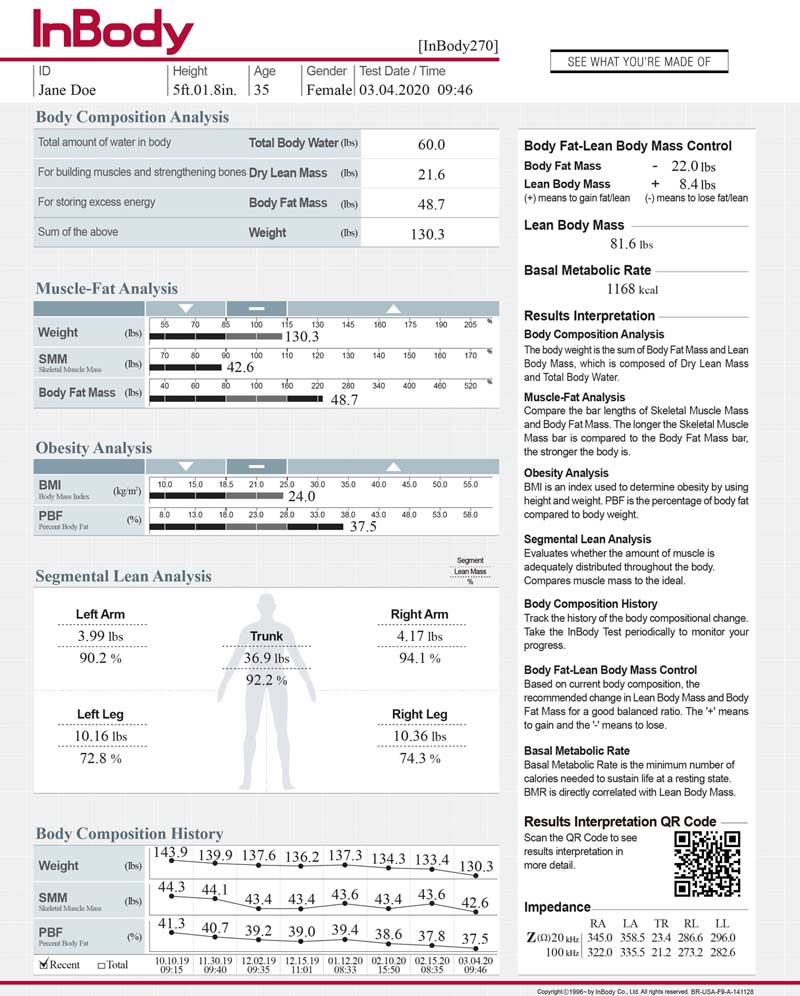

- Body-composition tests (I personally do not perform these because I am at the high school level)

-

- Change of direction tests

-

- Max power

-

- Sprint tests

-

- Muscular endurance

-

- Anaerobic capacity tests

- Aerobic capacity tests

These are all just potential examples. Every sport is different in some way, so make sure you customize your test battery to cater to the demands of the sport.

Change of Direction Testing

The ability to change directions is key for most team and individual sports. These types of assessments are typically performed well by those who can achieve higher velocities in linear speed assessments. However, in my experience, many coaches (especially in football) do not always value linear speed and believe change of direction tests are better at evaluating “game speed” and ability.

If you follow the NFL and its combine, you’ve probably heard of DK Metcalf. He had a blazing fast 40-yard dash but a poor three-cone drill (commentators even mentioned how it was worse than Tom Brady’s). DK Metcalf has been doing just fine in the NFL despite his three-cone drill results.

Some other assessments made popular by the NFL combine are 5-10-5 (pro-agility shuttle) and the L-drill. However, you can always create your very own change of direction test and customize the angle of the direction change, which can range from 45-180 degrees.

I would caution coaches against making the test longer than seven seconds so as to keep the test anaerobic and alactic. I imagine these tests to be power/speed tests more than anything else. For example, 300-yard shuttles are assessing something much different and are not an evaluation of change of direction in my opinion.

Change of direction tests can also be used to evaluate asymmetries. Evaluating an athlete’s performance when pushing off or changing direction on both the left and right legs can be important in determining if the athlete is proficient at absorbing/producing force on both limbs.

Change of direction tests can also be used to evaluate asymmetries, says @KCPerformance_. Share on XAssessing both limbs is important for understanding potential movement problems or deficiencies. An athlete with a large deficit between their limbs could be at risk for injury. Knowing how each limb performs independently can also help determine if an injured athlete is ready to return to play based on their test scores in rehab.

The Freelap timing system can be used to time change of direction tests as well. Visit the SimpliFaster YouTube channel and you will find informative videos from Christopher Glaeser on how to do this.

If you do not have a few hundred dollars to invest in a Freelap timing system, there are more affordable options: Dartfish Express is a film analysis app (that costs about seven dollars) which has a built-in chronometer that can be used to accurately measure time down to one hundredth of a second. If you want to be able to export the videos, you have to upgrade to Dartfish Mobile, which is five dollars per month.

Linear Speed Testing

This is the test that can literally change the course of an athlete’s career. Many colleges are heavily recruiting based on speed these days, and if an athlete is not performing well in linear speed, colleges probably will not be taking a chance on them—no matter how impressive their high school highlight tape is.

The most popular linear speed assessment in the states is the 40-yard dash. This again is another test popularized by the NFL combine, but other sports have their own linear speed assessments: MLS uses a 30-meter dash test and the MLB uses a 60-yard dash test. They all are evaluating linear speed over different distances.

Make sure you are using a reliable timing system. I reached into my own wallet to purchase my own Freelap timing system for my school. Having a reliable timing system will increase your value as a coach. Working at the high school level, I have had the opportunity to time hundreds of athletes. Timing sprints is great to see how athletes are performing and gives them perspective on their abilities.

During my first year at the high school, before I began working with the football team, the starting running back tore his ACL. I tested him in the off-season, after he had recovered from his ACL tear, and found his 40-yd dash time to be less than stellar: 5.28. That is a below-average speed for a starting varsity running back. I explained to him that this was an area in which he needed to improve and that he had not had a carry over 20 yards the previous season, nor did he score any touchdowns. That athlete ended up training at a private facility that performed zero speed work in training.

Flash forward to his senior year, his 40-yd dash time barely improved to a slightly-less-slow 5.23. He lost his starting role to a sophomore who had been training with me for the previous two years and ran a 4.87 40-yard dash. Not blazing fast, but a very respectable time for a 16-year-old in a small school.

Visual feedback is one of the best tools for me and my athletes, says @KCPerformance_. Share on XEven though I have a fully automatic timing system, I still like to film my athletes’ reps from time to time. Visual feedback is one of the best tools for me and my athletes. A high school lineman sprinting with excessive butt-kick and over-reaching is hard to cue simultaneously, and it may be even harder for them to understand what I’m trying to explain.

Filming the rep and showing them what I see and what I want them to change or focus on has made technical improvements happen much quicker than before. It still takes time and patience but change happens sooner with visual feedback.

Unrealistic Training Expectations

Training high school athletes means you have to deal with parents. Parents have very high expectations and sometimes even unrealistic ones. If you train athletes outside of school for money, these assessments are essential for evaluating the athlete to show exactly what their abilities are. It is important to compare the athlete to other athletes their age, but also to collegiate athletes so the parents can understand which physical qualities are necessary to compete at the next level.

If the athlete’s profile is not great, be positive with the parents and athlete, but also realistic. Sometimes an ego can be crushed but it is our job to turn that into motivation.

Athletes and parents alike need to understand that training is a long process. If they come to you as a sophomore hoping to play in college, you have time to improve their athleticism with smart training, but nothing significant will change after a month. If things don’t improve after a few months, then please do something different in your training.

Try not to rely on hand timing or using your timing system incorrectly, so times will not be inflated, says @KCPerformance_. Share on XFollow the best protocol that the equipment offers and, as previously stated, make sure it is precise and reliable. Try not to rely on hand timing or using your timing system incorrectly, so times will not be inflated. Now more than ever, social media has given us absurd fly-10s and 40-yard dashes at the high school level; all that does is give your athletes a false representation of their actual abilities. Buying a timing system is not to fuel egos or post social media videos for the sake of it—use it to collect accurate data to evaluate athletes.

Jump Testing

Jump testing is a good way to determine jumping ability, but also lower body power and elasticity. I personally like measuring a squat jump, counter movement jump with hands on hips, counter movement jump with arms, and RSI.

A lot of jumping test results I see on social media are inflated due to athletes understanding how to cheat the test by manipulating their body to increase flight time and delay landing. Make sure your athletes understand the directions before they jump. A squat jump should not have any counter movement or that will inflate numbers as well.

Don’t worry if you cannot afford a jump mat or force plate. Carlos Balasobre-Fernandez is the creator of My Jump 2, an inexpensive app that uses the camera of your smart device to film and analyze vertical jumps, horizontal jumps, RSI, force velocity profiling, and right-left asymmetry jumps.

I like testing both legs separately to gather information to see if there may be a huge asymmetry present. This could provide valuable information that a limb is at risk for injury. The app has been proven to be reliable and objective in research and is a fraction of the price compared to jump mats and force plates. All that is required is a smart phone with a camera and a couple leg measurements of the athlete, and you can collect jump data.

Obviously not many sports require great jumping abilities to be successful. Jump testing will be more important for basketball and volleyball, but the information gathered from jump testing is still important. Jump tests can track athletes’ readiness as well. But maybe the most important guideline for jump testing is making sure the athletes are giving 100% effort.

The most important guideline for jump testing is making sure the athletes are giving 100% effort, says @KCPerformance_. Share on XOver-testing jumping abilities could become monotonous and boring, leaving the athlete to appear as if they are not improving when they might just be lacking motivation. Read the room; if the energy isn’t there to collect good jump data then reschedule it for another day.

Fitness Testing

Fitness testing is a way to measure if the athlete’s energy system is robust enough to keep up with the demands of the sport. There are several different fitness tests that field sports can use to evaluate this. Football requires a different level of fitness than soccer, and this can be analyzed even deeper by breaking down the demands per position.

A few similar and popular tests include the shuttle run beep test, yo-yo intermittent tests, and 30:15 intermittent fitness tests. These named tests have shown reliability in closely predicting maximal aerobic speed. At the very least, this test gives a good indication that the person has the fitness or running speed necessary to compete in intermittent field sport.

Think of these intermittent fitness tests as showing how fast an athlete can run in-game versus the linear speed test which shows how fast the athlete is capable of running. Some will debate whether these test results truly test aerobic capacity or just the ability to run shuttles with short rest periods. These tests are not perfect; for instance, some athletes who can achieve higher sprinting velocities can do well on this test even if their fitness or aerobic capacity may not be stellar.

Martin Bucheit has an app named 30-15 IFT, which essentially talks the test-taker through the test. It works best if connected to a speaker that can be brought to the field. Athletes can listen to directions as they complete the test. The app is free and is available for iOS and Android.

A popular test I see at the high school level right now (and one I do think has merit), is the simple 1.5-mile run test. I think it is a fair assessment of aerobic capacity during running. If an athlete performs poorly, it might be a sign that they cannot sustain a decent running speed for an extended period of time.

A lot of people think a test like this will kill an athlete’s sprinting velocity and that all their hard work during off-season speed training will be a waste. To this I say: it is just a single test. Most team sport athletes need to be able to maintain the skill of running for an extended period of time. If running 1.5 miles makes you as a coach or your athletes nervous, then they may be out of shape.

Show Your Value

Coaches usually know if they are making a meaningful contribution to their school or athletes. Making a large positive impact means you have value. But do other coaches know that about you yet? If the answer isn’t definitively yes, then it’s time to change how you go about things.

When I first started out at the high school level, coaches just thought I was there to teach kids to lift weights. They were confused when I would take them outside for speed training. Now they understand the real impact I can bring to their teams. Coaches seeing their players power, speed, and conditioning increase each year on paper is great, but when they also see it translate to game play is when you gain the coaches’ trust for real.

Set yourself apart by using technology to improve the way you record data and gather information. The technology and apps suggested in this article are tools that I have used successfully. Technology should not create headaches or create more questions than answers. Make sure you are collecting the data you want to collect.

Set yourself apart by using technology to improve the way you record data and gather information, says @KCPerformance_. Share on XFreelap has given me the ability to gather information quickly and efficiently while the inexpensive apps have helped me collect important data I thought I couldn’t collect without expensive equipment. These suggestions have been a game changer for me and my athletes. New technology has made assessing my athletes easier than ever.

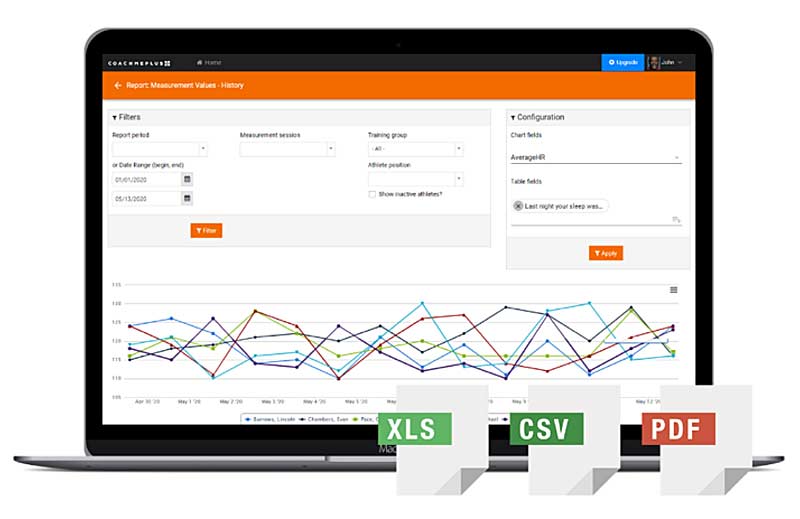

Work With Your Coach

What do you get when you combine all these assessments? Despite the small budget, a pretty solid evaluation of athletes’ strengths and weaknesses. You can even create diagrams and athlete profiles to show the coach so they can fully understand the meaning of the results and what to do with them moving forward. If a coach accepts your offer to perform the testing battery, it is a sign that they’re probably open-minded and willing to hear your feedback.

Don’t forget to retest these qualities to evaluate how the season is affecting certain physical qualities and report back to the coach. Great coaches understand how to smoothly embed testing in practices during the on- and off-season without it feeling forced. Seeing positive results after retesting makes sport coaches happy and gives you the opportunity to continue to work with the team.

Remember to evaluate your demands of the sport before choosing these assessments. Use what is useful to your sport and ditch what is not relevant.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF