Austin Jochum is the owner of Jochum Strength, a sports performance facility in Minneapolis, Minnesota. A previous Division 1 strength coach, Austin left the collegiate sector in 2022 to dive fully into the world of private athlete training and skill acquisition.

He is the host of the Jochum Strength podcast, where he has elite-level guests guide him down the rabbit holes of the sports performance field, and he also operates The Jochum Strength Insider—an online training platform for people trying to feel, look, and move better. Austin was a D3 All-American football player and hammer thrower at the University of St. Thomas and is a slow pitch softball and pickleball addict.

Freelap USA: What were some of the biggest challenges of working in the collegiate setting while simultaneously building your personal business and brand? How did you manage your time between the two sectors?

Austin Jochum: I truly think a balance of the collegiate and private sectors is where the future lies for most schools that “can’t afford” a strength coach.

I learned early on, from listening to coaches I respected, that if you really want to succeed in the college sector, a secondary source of income is necessary to allow you to stand up and say what you need to say without your entire paycheck relying on every word. I think that’s why you see so many “mini me’s” and clones in our field—if you speak out and bite the hand that feeds, the consequences could quite literally be your career.

If you really want to succeed in the college sector, a secondary income source is necessary to allow you to stand up and say what you need to say without your entire paycheck relying on every word. Share on XI felt that my family had made too many sacrifices for the opportunities I have been granted to waste it all on doing something because I “had to” or because someone else told me to. Income from the private sector allowed me to say no to a lot I otherwise would have had to say yes to.

On the other end, the college sector provided me with a steady source of income that I could rely on to funnel into the gym during the dark days when we were just getting started and training people for free. I was actually “homeless” and slept on my gym floor for my first three years in the field because everything I made went into the private sector gym until it took off. So, it’s not all sunshine and rainbows. But in the end, it was worth it.

I also think the college sector gave me real skin in the game with the hundreds of football athletes I had to work with and prepare every single day for a season. This is where the private sector gurus can get a little disconnected when they talk about setting up some “individualized one-on-one program.” That *works* in the private sector but falls apart quickly when you’re faced with somewhere between thirty and one-hundred 18- to 20-year-old athletes who slept for three hours the night before and don’t know the difference between a bicep and a tricep. That makes you a much better coach very quickly, and I use these skills in the private sector every day.

Freelap USA: You’ve spent some time as a strength coach for a high school dance team. In the past, dance was not something that considered the benefits of strength and conditioning. How important do you think it is for dancers to incorporate some type of strength and conditioning program into their schedule, and why? How does the training differ in comparison to more traditional sports such as soccer or basketball?

Austin Jochum: The biggest dance coach in the nation, ha-ha!!! This was truly one of my favorite gigs—the energy of 20-30 teenage girls is unmatched. Most of their training ages were honestly so low that everything we did looked and felt like magic to them. Dance is a sport that is massively into the “early specialization” category, with it being the only form of physical activity some of the girls have ever done, since they were four years old.

When you repeatedly force the ever-adapting body into one box, it tends to rebel, and you see young athletes with the wear and tear of an older athlete. Give the body what it desperately craves in variation—go from s**t to suck to good in basic movements and emphasize the law of diminishing returns with them, and you’ll get some pretty awesome results.

Like every athlete I train, it doesn’t differ a lot—we just level up the body and then let them do the cool things in their sport. Repeat this process for days, months, years on end, and you can get to a level most wouldn’t even dream of. The problem comes when most can’t stick to something for even a week…

Freelap USA: Athlete movement signatures and creativity is something you emphasize with your youth athletes. How do you build these exercises into your program? Do you apply any parameters or leave the athletes to their own instincts? What do you do for athletes who are sometimes more shy or standoffish when it comes to creativity and thinking outside the box?

Austin Jochum: I’m going to emphasize here that we do this with ALL athletes not just our youth. A pet peeve of mine is the apologist who always backs a movement practice tweet or social media post with “it’s just for the kids—eventually we will get serious.” That doesn’t make sense to me because:

- When did these movements become any less important?

- If you watch most older athletes, given the current state of sport specialization and weightlifting, many are pretty terrible at a lot of these foundational pieces of movement.

I have seen athletes who can bench 405 but can’t crawl for longer than five minutes without breaking down. To me, there’s a much greater bang for your buck in focusing on things they are not good at and have not done than in doubling down on something that they have already mastered. Our goal is to create learners and lovers of movement and skill acquisition—that does not happen when you give them the same drills and lifts over and over again.

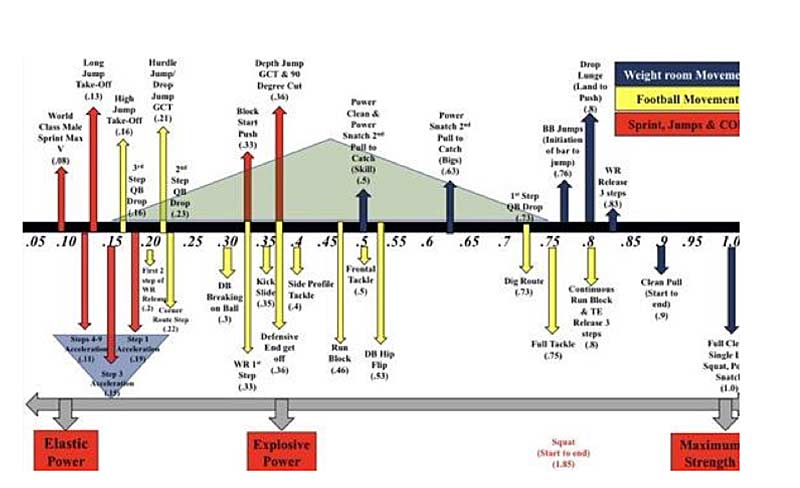

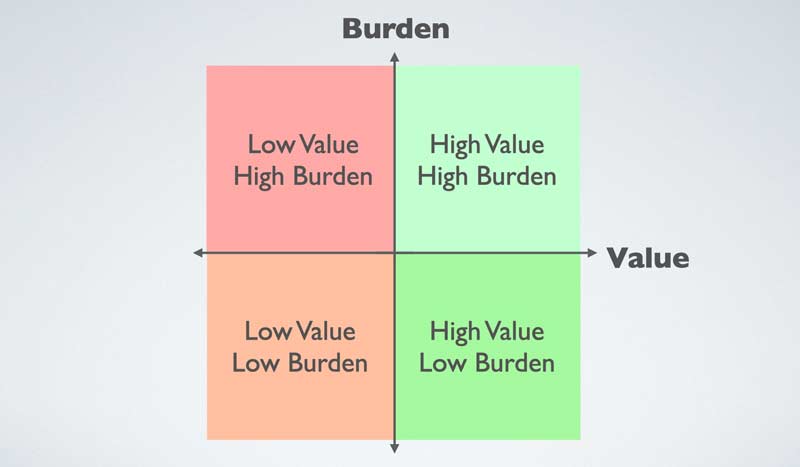

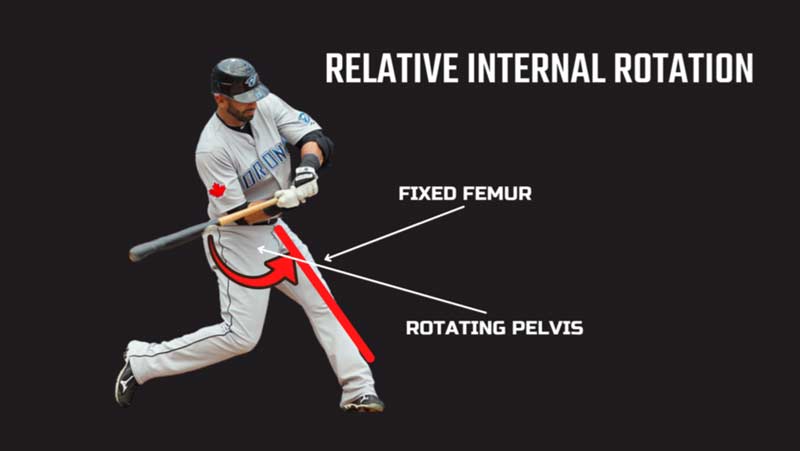

Image 1. Train, unlock, level up.

My focus with most athletes is to just let them athlete! Give them a ball, a goal, a movement problem, and let them figure it out. When they do—change the problem. Repeat and play with this process, and you can come up with some pretty spicy warm-ups and movement problems, all while creating adaptable and resilient athletes.

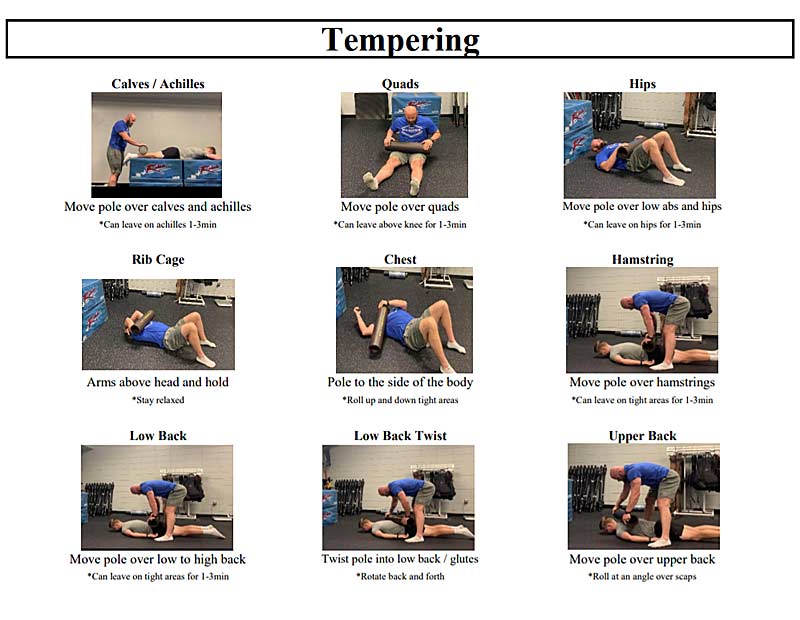

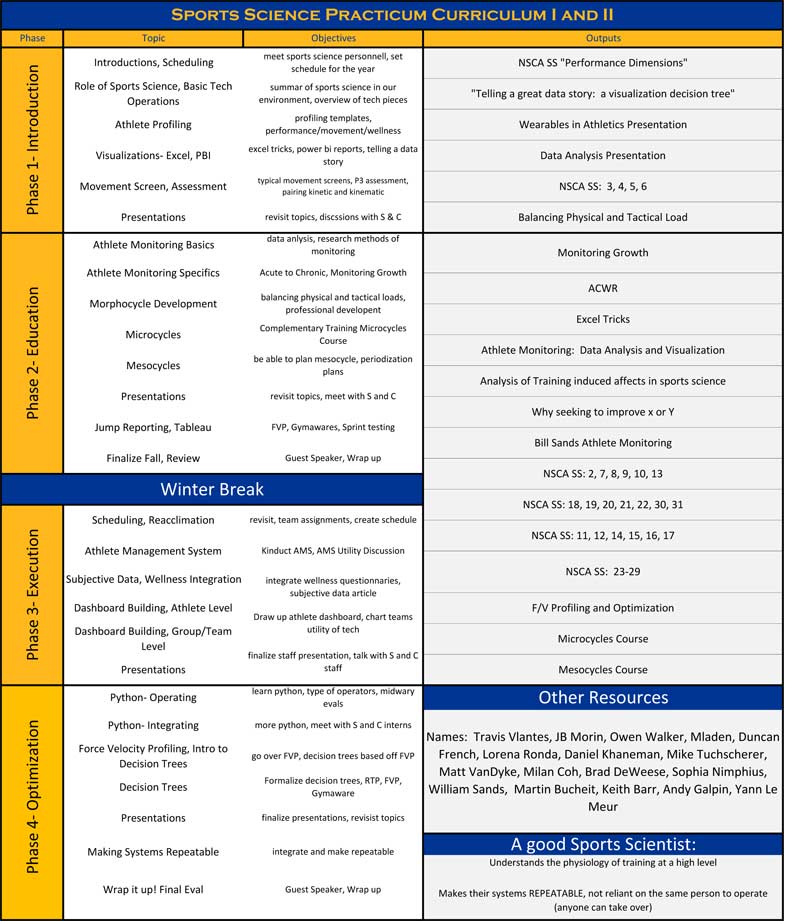

Image 2. Agility games.

If you value this creativity, you should reward it. When looking back on my career, I think about why I liked lifting heavy weights. The answer was simply because I was good at it, and my coach always rewarded it—whether it helped on the field or not.

As a coach, you have the power to get your athletes addicted to this movement exploration. My goal for all of them is to pursue the question “what is my body truly capable of?” Oh, I learned how to do a cartwheel! What about a handspring? Keep this questioning going, and eventually they will realize they are truly capable beyond belief, and they will start to bring it to their sports practice. Oh, I can make him miss this way. Oh, what if I set her up like that and pass the ball that way? Oh, I can throw the ball from that angle!

Double down on this creativity, and let the athletes do what they do, or take it away and the greats will ignore you anyway.

Freelap USA: Your athletes perform a lot of heavy positional isometrics and for extended periods of time. How do you incorporate this into your programming? What benefits have you seen in their training? And how do these isometrics affect the mental approach and mindset of your athletes?

Austin Jochum: Isos are a funny topic for me because it is so hot button even though they are probably one of the oldest forms of movement and exercises we have.

We use isos in a multitude of ways. We use heavy positional isometrics to master positions, stimulate, and prime for the high-speed or output-based activities we will do that day, whether for plyos, sprints, or jumps.

Normally, these take the place of our “main lift” for the day. I view a stimulus as a stimulus and value our typical “progressively overloaded barbell strength” work less than most coaches.

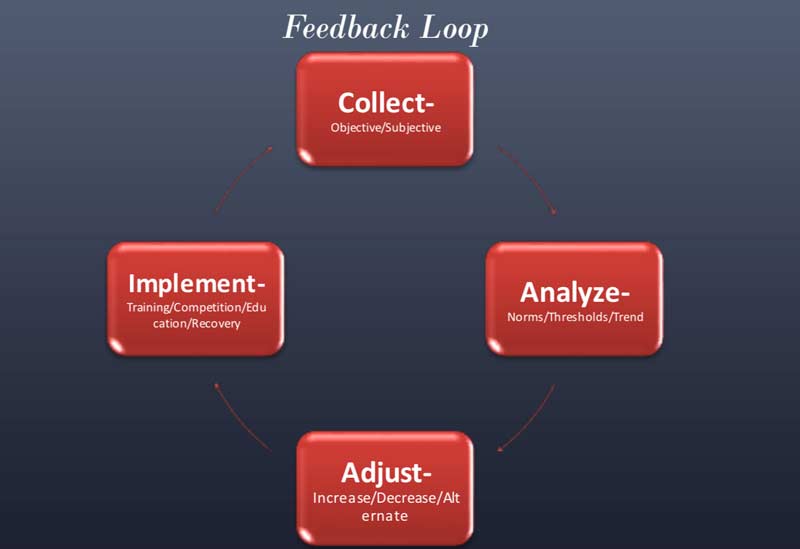

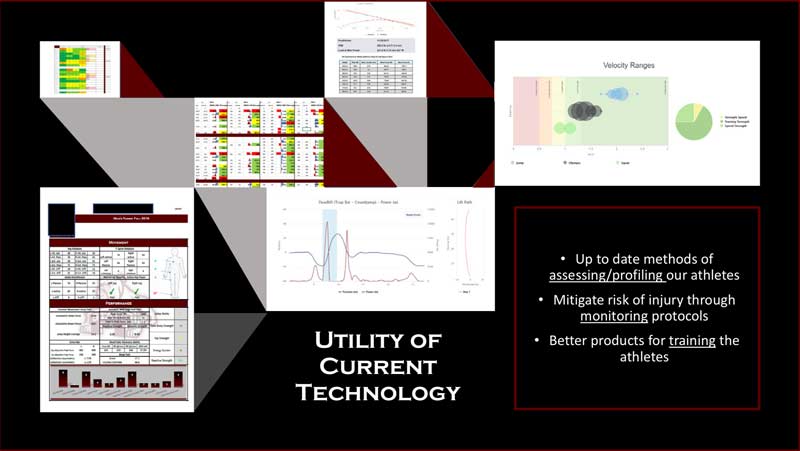

Image 3. Heavy isometric variations.

To me, squatting 500 pounds is just the ability to master the squat pattern. How does it carry over when you have to hold that weight in a different position or for a different set amount of time, or MOST IMPORTANTLY, the object you have to move suddenly has legs, arms, and a brain with the goal set on not letting you move it? I want our athletes exposed to as many “strength” positions as possible—heavy isometrics are just one of those.

I want our athletes exposed to as many “strength” positions as possible—heavy isometrics are just one of those, says @AustinJochum. Share on XLong-duration isometrics are where the mental side of the game comes into play for us. (Along with the physical benefits of “building the armor” and working on leveling up of the body.)

In our field, we talk all day about the importance of the psychological side of the game, but most of it is eye wash to me because then coaches program with the thought process of making sure they can check the boxes of “unilateral push – bilateral vertical pull, etc.”

When I look at a program, I try and keep the mental flow of things in mind.

We start every day with an external stimulus and dopamine spike in the form of some sort of game or creative movement problem. The goal here is to give athletes full control (as most come from a day where they just had zero say in 99% of their activities, going from teachers to coaches to lunch ladies.)

Then we use this dopamine spike and plug and play into our main stimulus of the day—jumps/throws/lift/sprints.

After all of this “high,” I want to see who can draw themselves back into their own bodies—like the ebb and flow of a game, where you play and then must go sit for a timeout or change of possession.

This is where we introduce the isos. You just broke a PR in a jump and lifted a ton of weight to loud music and everyone was cheering—sweet! Now can you draw yourself back together and hold a position for five minutes straight? Can you stay still? How do you handle your emotions in that moment?

Starting off, most athletes feel the desperate need to move/wiggle/fidget or have emotional outbreaks of anger or doubt. This is a beautiful time to have a conversation with them about this. Why do you have to move? Why are you getting angry? Why did you quit there?

These conversations are really where you can work on the mental side of the game and life. If it is happening here—with no fans and no game-like pressure—imagine where the mind goes with all this added external stimulus!

It’s almost a movement meditation, in a sense. This is often a great introduction to real meditation—the best isos there are.

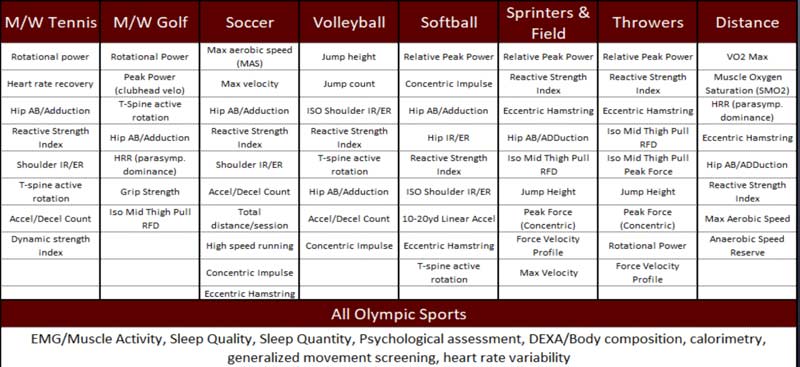

Image 4. Forced adaptation.

Freelap USA: The motto of your brand is “keep chopping wood.” What does that mean to you, and how do you apply it with your athletes and your training?

Austin Jochum: When I was a freshman in college, I was on my way to quit the football team and transfer to a rival school that was closer to home. I was a seventh string fullback at the time: injured, unathletic, and didn’t think I’d make it. I was making all the easy choices in life and almost went through with the worst one of them all. On my way to tell my college head coach, I texted a high school teacher and coach of mine, Coach Herm, and told him the news.

He promptly texted back, “That’s not who you are—Keep Chopping Wood.” That one text prevented me from taking the easy route and kickstarted everything that I am currently doing in life!

I ended up as an All-American in football, got to play in a national championship game, found a love for hammer and weight, and became a conference champ there. I jumpstarted my coaching career because of the connections UST provided me with. All from a simple text: “Keep Chopping Wood.”

It’s the process of every single day, swinging the axe, doing the work that needs to be done, and repeating this for years on end—for no other reason than you know it’s your duty—then watching the amazing things you can accomplish in life.

It’s the process of every single day, swinging the axe, doing the work that needs to be done, and repeating this for years on end, then watching the amazing things you can accomplish. Share on XWhen an athlete realizes this, the potential for what they can do goes through the roof. The craziest part of all of it is that Coach Herm doesn’t even remember sending this text. The message that completely changed the direction of my life was just a text that he probably sent quickly on his lunch break before he got back to work—because he is an amazing person and cared!

It makes me think about the impact you have on others every single day with words you don’t even remember saying. You have the power to change the world to one you think is better than the current one. Continue to do it yourself, continue to pick up the axe every day, and then remind others they can do the same.

Keep Chopping Wood.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF