If you were asked what muscles your eyes are primarily made up of, could you answer without Google? Simple enough question, right? Maybe right now you are looking left, right, up, and down, probably thinking about how all the type 2 fibers that make up your eyes are helping you do that.

At the same time, though, our eyes need to see and provide us with information for long periods of time. They need to remain open to do this yet blink quickly when necessary to reset. With all the quick movements, like blinking, it still would seem to be predominantly quick twitch based. However, could those long-duration uses serve to show otherwise?

Regardless of whether you’ve figured out the answer to the eye question, we’ll come back to it later. Clearly, the eye shows the need for all systems to work together for both short- and long-duration movements, just like how all energy systems need to work together and cannot be treated entirely in isolation, independent of each other.

Many have looked at sprinting in a similar fashion. Max speed doesn’t last beyond five or six seconds, so why sprint for any longer than that? Anaerobic systems are the only energy systems being used then, so why do we need to focus on other energy systems? Most sports actions don’t occur at submaximal effort, so the focus for everything sprint related should be all-out and with good rest. And the kicker—these sport actions and plays tend not to occur for longer than that 5- to 6-second time span, so there’s a high-enough rest:work ratio anyway.

While those arguments may all sound good, it can be quite easy to poke some holes in those claims. While maximum speed may only be held for 2-3 seconds, speed endurance—the ability to hold speed as long as possible and delay deceleration—can be crucial, as numerous plays occur for more than three seconds in sports. Although fewer occur at submax than at maximal effort, shouldn’t an increased recovery ability be something to look for, especially since energy systems all work harmoniously with one another as opposed to only working one at a time? And if and when the worst-case scenario occurs, all should be prepared to succeed at that point.

While it may not seem intuitive to train slower in order to gain an advantage, tempo has a place for almost all athletes, says @sgfeld27. Share on XBearing this in mind, when working with team sport athletes, using tempo sprints as part of training can have great benefits. While it may not seem intuitive to train slower in order to gain an advantage, tempo has a place for almost all athletes. While Ryan Banta has already shown how tempo training can be used for sprinters and Mike Whiteman has discussed why tempo is great for sprint ability, let’s really dive in to understand how we can use this method to an advantage with baseball players.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9096]

Technique and Rhythm

The benefits of sprinting and its effects on the central nervous system and overall speed cannot be overstated; attempting to run at maximal speed, however, is no small task. Because of the inherent nature of attempting to run as fast as possible, there are drawbacks. For instance, technique will likely not remain perfect or even close to it for whoever is sprinting, especially if they are not a trained sprinter. In turn, relaxation can also be lost in this attempt at maximal output.

Enter tempo training.

There is more opportunity to view technique and rhythm when slowed down than when the aim is solely full speed. Rather than running at maximal speeds, depending on the intent of the tempo on a given day, athletes can be going anywhere from 65%-90% effort and/or speed. In these speed ranges, homing in on technique, rhythm, and relaxation—and truly coaching it up—can be the primary focus.

Enter tempo training: There is more opportunity to view technique and rhythm when slowed down than when the aim is solely full speed, says @sgfeld27. Share on XForgive me as I digress, but I believe there is a necessary connection to make here between sprinting and lifting. Although they are not the same, there are some parallels. I find it stunning that some coaches will allow sprints to be used when they are ONLY fully max effort and/or max speed. When athletes are in a weight room, are they just in there to max out, whether it’s a one rep max or a five rep max? Or is the weight thoughtfully and carefully programmed? Hopefully, these answers don’t need to be provided to be known.

Furthermore, when athletes do max out, how much are we coaching them up for technique compared to when they are lifting submaximal loads? Maybe there is a reason maxing out seems to occur less and less often in programming for athletes (could an ever-improving use of velocity-based training metrics be part of the cause?). And while other accessory exercises help supplement our abilities on lifts where we may max out, they are just that—supplemental—in the same way that sprint drills are supplemental to sprints.

If we use velocity-based training metrics in the weight room, but agree that sprinting is the true means of velocity-based training, then it seems we have a big gray area to fill in. While the weight room can provide us with peak and average speeds in the 0.3-3 m/s range, sprints at the absolute most elite of elite speeds are about 12 m/s. A gap from 3 to 12 is far greater than a range of just 0.3 to 3. Even if we cap team sport athletes between 9 m/s and 11 m/s rather than using 12, the gap remains fairly unchanged.

Part of what makes tempo a great tool is that it fills in the gap of speed that is left if we only chase max velocity sprinting and weight room-based velocity. The gap that was about 3-9 m/s narrows to the 3-5 m/s range when we incorporate tempo running. When we use 65%-90% and program tactfully, all of a sudden, the ability to make meaningful technical improvements in sprinting becomes far easier.

Part of what makes tempo a great tool is that it fills in the gap of speed that is left if we only chase max velocity sprinting and weight room-based velocity, says @sgfeld27. Share on XUsing submaximal paces can help in both a straight line and an arced trajectory. For any athlete, the ability to improve technique should absolutely help diminish the risk of injury while sprinting. For baseball, learning better mechanics in both planes translates right to field work. As athletes develop better technique, speed development becomes easier and far more fluid and relaxed. Learning how to find the feel of a certain percent effort or speed can help make learning to use specific speeds much more effortless.

As players constantly throttle through different speeds in games, the ability to own those speeds and techniques outside of games is highly important and gives a big reward at a minimal risk.

Planning for the Worst-Case Scenario

While we do a great job in reverse engineering sporting demands to prepare our athletes with complete holistic programming, I believe that preparing for the worst-case scenario is often an overlooked consideration. Maybe I am wrong, and it is perhaps just not spoken of as much. (I thank Dan Howells for adding this concept to my thought process in programming.)

So, what is it that makes tempo training a way to help plan for the possibility of a worst-case scenario occurring?

Within baseball, there are a few different ways to define what the worst-case scenario may be. From a general fitness and heart rate standpoint, being trapped in the sun and draining heat of summer during a long inning is a potential problem. What happens when you can’t get water, hide in the shade, or take a seat on the bench because your team just can’t get the other team out? Sure, hydration plays a factor here, but regardless, if you are not in decent enough shape to control breathing and heart rate for a long time frame, can you still be in an optimal spot? What if you are the pitcher, and it’s a long, 30+ pitch inning for you at this point? While the sport is primarily anaerobic based, there is still clearly a need for an aerobic base due to potentially long innings.

On the flip side, offensive players may have to make repeated sprint efforts numerous times in a short period, depending on how the inning is going. Especially if you have a speedy base runner at bat or on base, base stealing, hit and run plays, and extra base hits are all possible. All these situations mean guys will be sprinting anywhere from 10 to 120 yards in any given situation, and while they may not always reach max velocity, they also in all likelihood will not always have proper rest time with 30 seconds between pitches.

As with Zach Dechant’s example situation, 93% is not only barely above intensive tempo pace but also not quite max velocity. This is not to say maximum effort or intent is not present, but we must understand the demands to prepare for in a worst-case scenario. Yes, we must be ready for high-speed running, but we also need to have the ability to either hold near-max speed for a sustained time or repeat efforts on short rest too. Only running maximum velocity or intent on proper rest will miss the boat on this.

Finally, because baseball is an outdoor sport, the weather has a big effect on scheduling. It is an uncontrollable aspect that can wreak havoc on a schedule if the weather is bad for any period of time. Double headers and postponements are not uncommon as a result, and with those automatically come extra innings on any given day. On those days, guys have to be ready to make more plays no matter what, and more pitchers than usual will likely be used—meaning they also must be ready for shorter recovery before they pitch next. Without training geared toward this, we can expect long days to end with less-than-ideal results.

Worst-case scenarios are different from sport to sport, but the principles remain the same—as such, tempo training provides an excellent tool to ensure the preparation is met within baseball. Share on XWorst-case scenarios are different from sport to sport, but the principles remain the same—as such, tempo training provides an excellent tool to ensure the preparation is met within baseball.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9066]

Off-Season Preparation

As with plyometrics, tempo has both extensive and intensive options. When it comes to off-season preparation, extensive helps prepare for more intensive work down the road. Furthermore, using extensive tempo from the start of the off-season provides an opportunity to build workload and tolerance.

If we are to adequately prepare our athletes for the long season, we must work them above the levels they will be worked during the season. Using tempo as a base provides an opportunity for numerous ground contacts that will quickly ramp up the moment spring training begins. This includes all contacts—those we focus on and those we don’t always think of as important—all the time just spent in cleats, shagging balls during batting practice, moving from field to field, etc. The contacts are endless, and as such, we must have proper preparation. Without it comes higher potential for injuries.

While tempo training may not be the top priority for a baseball player, even in the off-season, mixing it in correctly will pay a big dividend once the season begins. If we do not use it successfully during the off-season, how can we plan to use it properly in season?

Recovery and Peripheral Adaptations

Whereas sprint training aims to tax the central nervous system while building up max velocity and/or acceleration speeds (depending on the phase), tempo aims to help with recovery and circulation. Although it may not be accessible to all, a Moxy Monitor provides a great way to measure oxygen uptake to see that the stimulus provided gives the response we look for. If you are unfamiliar with Moxy or looking to dive into it, this is a great starting resource. Furthermore, standard heart rate monitors are a simple measure to ensure that heart rates don’t spike too high or fail to recover between repetitions and after sets.

Much like we use timing systems to monitor speed, measuring tempo runs and their intensities and goals with proper devices is helpful in understanding the systems within the body that we are working with. Anything can be great on paper, but until we see that the effect that we are aiming for is reached, we cannot prove we have accomplished our goal.

Without working this in during the off-season though, it is highly possible that tempo sessions could have negative effects on recovery come in-season phases. As the goal with tempo training is to improve circulation and recovery for pitchers between outings or position players on days where they don’t play (and therefore don’t sprint), we must ensure that these methods work as planned and use them throughout the year.

Implementation

With the season in mind, having a standardized test to train toward and focus on will help make tempo training easier to use.

*Note: Just because there is a tempo test does not inherently make this the priority over anything else. Rather, it truly is a way to standardize procedures and provide athletes with an understanding of what tempo is being used for and why.

Testing Protocol

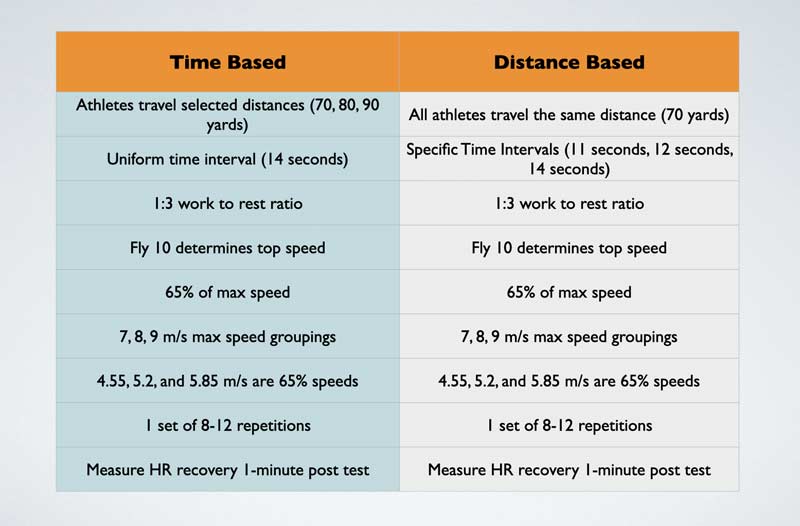

The table below outlines two potential ways to incorporate tempo testing into baseball training:

The time-based and distance-based options provide largely the same parameters. There are some crucial differences, however, that make the time-based option the better choice, in my opinion. None are more imperative than the fact that if, and more than likely when, you have players from multiple speed groups, it will be much tougher to stay well-organized with multiple different work and rest times going simultaneously.

So, what makes this 14-second test a good, dependable baseball tempo test?

Primarily, the 70- to 90-yard range. While longer than a typical baseball sprint, it is still a sprint that can occur within a game. It is in between the range of a double and triple (60 and 90 yards, respectively). It also uses the top speed of players and helps to individualize a group task, while still making this much easier to accomplish as a big group. While differences in speed are minimal based both on the percent of top speed being used and the shorter the distance used for a test, this yardage still allows for the subtle variations to be seen.

Modifying this is as simple as changing the percentage of top speed run at, with room to adjust to 70%-75% of that. As such, work and rest times would be shortened by one and three seconds, respectively. However, shortening the distance beyond where it is would make this far less reliable of a test. While 50- and 60-yard tempos can work on a general recovery day basis, when testing they clump times up too much, and we risk messing up the validity of our tempo test.

Consequently, this test should comprehensively provide insight into athletes’ abilities to control their heart rate, breathing, and repeat work abilities. This insight is pivotal in understanding the players we work with and helping guide their development.

General Protocol

While some may think of him as a rugby guy, Keir Wenham-Flatt has a tempo template that is absolutely worth your time if it is something you do not feel comfortable fully programming. Though it may be best suited for rugby, you can tweak the template to be more useful for whatever sport you may be training or training for.

Beyond using the test and/or the template for longer-term programming, tempo training should become a staple of a program. Within baseball, tempo training is a simple and apt modality that is easily scheduled no matter the phase of the season.

Once the season begins, tempo should primarily serve as a means to provide recovery for pitchers between outings, says @sgfeld27. Share on XThroughout the off-season, extensive tempo can be used once or twice per week in order to build tolerance for foot contact during the season and to prepare for season-long tempo tests. Once the season begins, tempo should primarily serve as a means to provide recovery for pitchers between outings. Because the goal of tempo in season will lean toward recovery modalities, keeping it on the extensive side will be the preferential way.

For position players, understanding the schedule and who is playing on a given day is of great importance—as is understanding the types of players and their potential roles on a game-by- game basis. While an earlier example showed only making it to 93% of max velocity, in a single game athletes were still recorded breaking 95% of max speed 19 times. That comes out to an average of just above twice per position player per game having a maximum or near maximum velocity sprint. Now have that occur for three straight days or six out of seven days. Or when a season has a long stretch with 14 or more straight days with a game.

Of course, the need to sprint and be prepared for sprinting is paramount. However, when games occur nearly daily for weeks in a row, how do we ensure that guys have the ability to perform well day after day? Clearly, during the season, games provide the ability to sprint—so outside of those times, it becomes that much more important to ensure we program to the demands of what is needed to make performance its best in-game. We cannot endlessly stack sprinting on sprinting on even more sprinting. Know how to use tempo training between games and on rest days for position players to help them recover and prepare for future games.

Lastly, “poles” is a word that can create intense animosity for sprinting and/or conditioning in the baseball world. Running poles is, fittingly, the most polarizing term within baseball. Sure, they may not always be used well; however, creating an absolute distaste for them is not conducive to using these markers in a productive manner. Using poles to help distinguish proper distance and timing for tempo can be highly advantageous. Proper context and programming are absolutely necessary, but psychology cannot be forgotten.

Know how to use tempo training between games and on rest days for position players to help them recover and prepare for future games, says @sgfeld27. Share on X[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11163]

Systems in Concert

While team sport athletes are not sprinters, their ability to have good sprint mechanics is still important. The goal should not only be to improve overall speed, but also to remain healthier and mitigate injury risks. If availability is the best ability, then having better sprint mechanics should remain a crucial goal.

Furthermore, while the aerobic system may not be the most “sport-specific” system to develop and train, our bodies don’t work with their systems in isolation. Although the eye may move fast and blink, it still primarily has a slow twitch muscle fiber typing; likewise, although tempo may not need to be used as often as sprint training, it still is imperative to place it properly within a program. All systems work together and neglecting any part of them entirely is a disservice to our craft—at the end of the day, context and prioritization are critical to using tempo training in baseball.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF