[mashshare]

I wrote a Romanian deadlift article for SimpliFaster some time ago. Since I’m not content to sit still, I continue to implement this lift in its purest form and with an expanding number of variations aimed at solving problems that can be answered by what is, at its core, a simple hip hinge movement.

In this article, I’ll cover more of the raw technical elements, as even with great guides being available, there is some consternation as to what constitutes a “pure” RDL and what mechanics we actually get from the movement. I’ll also cover implementation of complex contrast and clustered methods to the RDL and how we need to shift our thinking about the movement away from just considering it a mere assistance exercise.

RDL Technique and Its Potential Role in Hamstring Management

I see constant disagreement in the S&C community over hamstring muscle activation during the Nordic curl and whether it effectively activates the biceps femoris. During the Nordic curl, the muscle lengthening occurs at the knee joint and not at the hip and knee joint simultaneously, as can be argued with the RDL. From the McAllister et al. study from 2014, we see very high biceps femoris activation in the RDL like the glute ham raise, and their final suggestion matches mine: Train both GHR/Nordic type patterns and RDLs.

In most research, however, RDLs are loaded far too lightly. For instance, Boeckh-Behrens and Buskies (2000), who conducted an extensive EMG series, did not test the weighted Romanian deadlift with maximum weight due to “security reasons.” At least McAllister had people lifting double their body weight. This loading issue is where I suggest people rethink their approach to the RDL, as it should be given greater billing and not be consigned to the 3x 10-12 graveyard as a third- or fourth-string exercise. Its true potential shines at loads of 80% and far beyond.

In most research, RDLs are loaded far too lightly. Their true potential shines at loads of 80% and far beyond, says @WSWayland. Share on XRDL technique is something I suggest you take a deep dive on. I mentioned it in my original article, and you should also give this video from Mark Rippetoe a thorough watch.

Much consternation is expressed about knee angle, with no more than 8-10 degrees at the knee being optimal. The key consideration is that the knees just need to be slightly unlocked and the bar swept into the legs, allowing the hips to be pushed back to allow a deeper stretch. If the bar isn’t kept close, this creates a lot of sheer force through the back, upsets mid-foot balance, and generally spoils execution.

I find that advanced RDL users can still achieve good hamstring feel even with a knee that’s slightly more bent. This is because advanced users are confident in really pushing the hips backward to achieve greater stretch. Anatomy matters, too. It may seem silly to point out, but athletes with larger hamstrings will appear to bend their knee more.

Additionally, arm length will obviously influence termination of the hinge, as will hamstring flexibility. Therefore, giving out strict depth requirements really doesn’t work. Somewhere between mid-shin and the bottom of the knee is usually about right. Straps are generally fair game, as most athletes will struggle to keep a grip over long times under tension or with near maximal load.

Key Coaching Points for RDL

Here are some key cues for athletes doing the Romanian deadlift:

- Set bar high in the rack just below lock out.

- Set hips before you pull bar out of the rack to avoid overextension.

- Take a minimum number of steps backward—aim for 2-3.

- Contract lats and belly breathe.

- Unlock the knees.

- Lead with the hips backward.

- Keep the bar in contact with the legs. Keep the lats active throughout.

- Descend using feel in the hamstrings to dictate depth.

- If you feel the need to unlock the spine to go lower, that is low enough.

- Squeeze the glutes and press the big toe into the floor to reverse the movement.

- At the top, breathing and lat reset may be necessary on very heavy RDLs.

Cal Dietz and Chris Korfist changed the way I cue RDLs by encouraging toe up on the descent and a short big toe mechanic on the way up. I was initially wary, but they made a compelling argument. The idea is to root the foot and hook the big toe to the floor—a lot of people assume it means curling the big toe/foot, which is different. Rooting the foot and curling the big toe appears to prompt a greater contraction response from the glute.

By adding big toe drive to the RDL, I discovered two things: athletes felt the movement more in their glutes and bar velocities went up at a given load, says @WSWayland. Share on XI suggest checking out this great simple guide by Roy Pumphrey. The classic demonstration is of an ordinary RDL and then another where the big toe is driven into the ground. While test-retest has its shortfalls, it’s a great way to demonstrate the concept. By adding big toe drive, I discovered two things: athletes felt the movement more in their glutes and bar velocities went up at a given load. Some smart EMG usage in the future can hopefully figure out whether this is a real neurological phenomenon or an athlete intent issue.

Common Mistakes, and How to Polish Technique

RDLs, while outwardly simple, do have a number of technical pitfalls trainees can fall into, especially if they have faulty hinge mechanics. This ranges from just maybe adjusting grip slightly to having to give external cues and regressions to fix problems.

Unlocking the Knees at the Bottom

This occurs when the trainee attempts to go lower. They’ll often push their knees forward to find depth. This is countered by working on fundamental hinge mechanics, cueing pushing the hips backward, and then feeling for stretch in the hamstring.

Bar Drifting Away

This is often the result of not being active with the upper back. Cueing athletes to engage their back and lats will often result in them pulling the bar back into thigh contact. It’s important this is coached out quickly because, with high loads, this adds a lot of sheer force through the spine.

T-Spine Flexion as a Depth Strategy

Again, this is often a case of someone not having spent time practicing solid hinge mechanics. The same cue for bar drift often works well. If this occurs in heavier loaded RDLs, it is often a lack of good upper back strength, so focus on rows and practicing isometric horizontal pulling.

Overextension

This is more common with very heavy RDL users, who use lumbar extension to get a greater stretch in the hamstrings. While a small amount of extension is tolerable, overextension can lead to impingement and irritation of the lower back. By encouraging the athlete to find neutral and take a solid belly breath, it becomes much harder to use overextension as a setup. The other thing to check is that they are not overextending when they unrack the bar and not subsequently fixing their position.

Extreme Cervical Extension

While, outwardly, this seems like a small technical oversight, this is often a strategy used to maintain good spinal position and drive global extension. Encourage chin packing and building good mid-back strength. This is also a strategy we see if we employ snatch grip RDLs as an extension strategy.

Improper Grip Causing T-Spine Collapse

When the grip begins to open, athletes chase the bar with the T-spine. It may seem obvious, but using straps, chalk, and proper grip width close to the body can eliminate this issue. It’s an oversight that can stop heavy RDLs from being effective.

Supramaximal RDLs and Considerations for Hamstring Injury Prevention

I have written about supramaximal methodologies before, suggesting: “Compressed intensive training is a period in which we apply the greatest stimulus to accumulate the desired response in the shortest time possible—this is where we apply supramaximal training. Supramaximal training is one of the approaches that excites muscular physiologists, as it leads to rapid adaptations and a reduced need for the repeat exposures we get from the same contraction focus at submaximal loads. Time, as a commodity, is always in short supply.” It’s not for the faint of heart, nor the inexperienced.

This approach is how I have gained enormous ground in getting more out of Romanian deadlifts. Supramaximal RDLs represent the highest intensities we can achieve with this movement. Supramaximal RDLs are a challenge to the entire organism from head to toe—traps, posterior chain, grip, and the ability to withstand a certain amount of spinal sheer are all elements in the movement.

Video 1. Going very heavy requires excellent technique and patient progression of overload. Use a load that you know would be nearly impossible to perform strictly with a concentric effort.

The other important element that I believe supramaximal RDLs promote is quality lengthening of hamstrings fascicles. This is very difficult to do with the current schema of RDL exercises we see endorsed. I’ve talked before about the force/stability relationship at low velocities. Single leg RDLs, which seem to be an injury prevention/rehab staple, are limited in their usefulness. If you are going to make meaningful qualitative structural changes, you need load and lots of it, and that isn’t possible on one leg.

If you are going to make meaningful qualitative structural changes, you need load and lots of it, and that isn’t possible on one leg, says @WSWayland. Share on XBy making the most of bilateral facilitation, we can dig deep into what the hamstrings are capable of tolerating. Carl Valle had this to say on the subject: “Another reason I don’t do too many single leg RDLs is that fatigue of the low back needs to be considered, as well as time constraints. If I do three sets of heavy RDLs and use typical rest periods, it’s far more efficient than doing six sets to ensure both legs are trained with the same approximate load. While a fresh leg might be ready to go after the other leg is completed, the lower back is still used and needs a break.”

While I encourage the usage of supramaximal RDLs, this method comes with a few caveats. If your population is not very exposed to RDLs, start with conventional RDLs at submaximal loads and modest eccentric tempos to build tolerance. High-speed running athletes also need to be careful, as this type of movement will heavily reinforce hamstring tonus and tension. Performing this type of work with concurrent maximum velocity running would make for a poor combination. If you use them together, do it prudently.

A supramaximal block would then be best followed by band overspeed eccentrics (mentioned later in this article). This type of work for field athletes fits squarely into the off-season or farthest from competition periods. One positive is that repeat exposures build tolerance with supramaximal methods. A caveat is that this method has the potential to make some individuals incredibly sore. Supramaximal exercises slot into my programming for athletes with higher training ages. Anecdotally, I usually bring these in year 2 or 3 for athletes who spend several repeat off-seasons with me.

I use two approaches in sequencing supramaximal eccentrics, terminating mid-shin and supramaximal isometrics pausing somewhere between mid-shin and the knee. We do not perform one rep maximums, which require both a descent/lowering and concentric/upward lift, since a technical aberration here could be highly injurious. Instead, we do our best with doubles or triples as the jumping-off point for applying up to 25% more load to make the movement supramaximal.

Usually, I’ll have an athlete perform singles for durations of 7-10 seconds to keep the movement alactic, but also assure enough time under tension. Two spotters will then hoist the bar back to starting position. Lifting straps are allowed and even encouraged; the challenge here isn’t on grip, but on the posterior chain. Due to the concentric-free nature of this movement, I often pair it with something like heavy KB swings or light rack pulls.

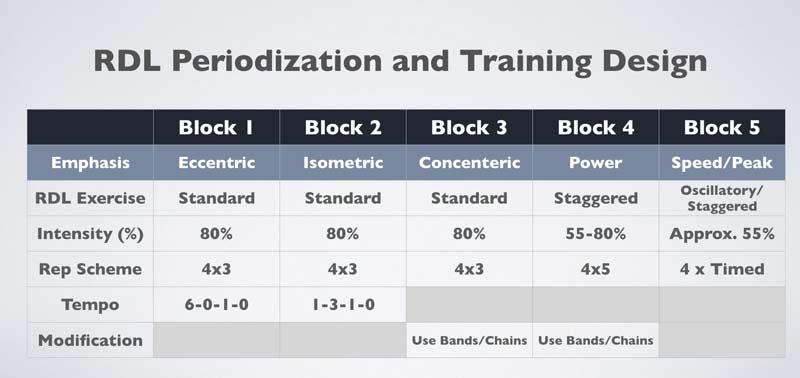

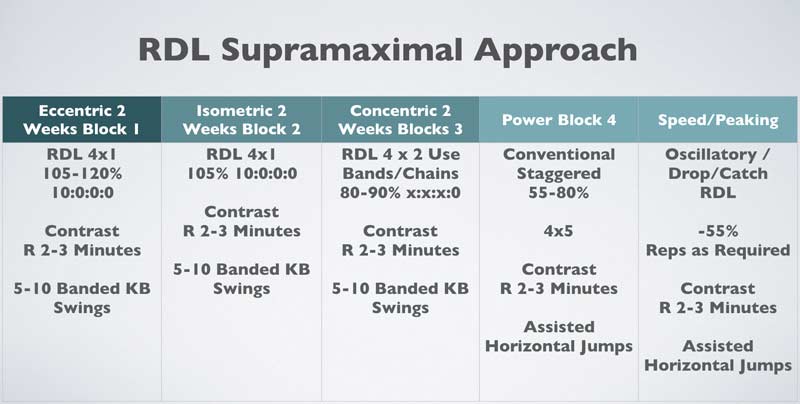

Table 1 below shows the conventional triphasic integration from the original submaximal approach, as outlined by Cal Dietz. While I still use this with athletes at lower training ages, I now look to include near or supramaximal loading schemes (table 2).

You can employ this as a compressed method, as I outlined in “Applying the Compressed Triphasic Model with MMA Fighters.” You can use supramaximal methods to spur rapid systemic changes when done prudently.

Contrast, Clusters, and the RDL

I’ve recently started adding contrast/complex and clusters to the RDL. I introduced this big change when I stopped considering the RDL just another assistance exercise and started seeing it as a performance driver. These can be bolted on with varying complexity to your conventional RDL programming. If you do decide to employ these methods, I suggest checking out this article on clusters and their versatility and this one by Joel Smith on complex and contrast training.

Video 2. Isometric exercises can help athletes break through stubborn plateaus when the primary lift slows down in improvement. KB swings with bands are also effective either for complimenting the isometric RDL or performed in isolation. I added contrast/complex and clusters to the RDL when I stopped considering it just another assistance exercise and started seeing it as a performance driver, says @WSWayland. Share on X

I won’t labor over the explanation of the concepts here, as I would just be repeating their main points verbatim. Contrasting is the simple method of having a heavy loaded movement followed by a mechanically similar movement, albeit at much high velocities to take advantage of the potentiation phenomenon and counteract the overactive braking heavy eccentrics can give us. By employing contrast exercises, we get a training effect across the V/F spectrum. I add these because the pure RDL is not a great power builder in competent populations. The best partnered movements I’ve found are banded KB swings, Dimmel-style pulls, and hinge-based horizontal med ball throws.

Example Contrast Methods:

A1) RDL 4 x 3

A2) Heavy KB swing or Dimmel deadlift 4 x 5

French Contrast:

A1) RDL 4 x 3

A2) Banded KB swing 4 x 5

A3) Overspeed RDL 4 x 3

A4) Horizontal med ball jump (holding on to med ball for assist) 4 x 5

Potentiation Cluster:

A1) RDL 4 x 1,1,1,1

A2) Med ball overhead throw 4 x 1,1,1,1

Performed alternating with moderate rest between singles.

French Contrast Potentiation Cluster (FCPC):

A1) RDL 4 x 1,1,1,1

A2) Banded KB swing 4 x 1,1,1,1

A3) Hang high pull 4 x 1,1,1,1

A4) Horizontal med ball jump (holding on to med ball for assist) 4 x 1,1,1,1

Performed alternating with moderate rest between singles.

The FCPC represents the most integrative, dense, and sophisticated of the above options. I suggest it only for athletes with the right training age, time, and space to perform all the necessary components. Having options like this available can help turn RDLs into performance drivers in combination with smart clustering and training density moderation.

Other RDL Implementations and Variations

The RDL family of movements includes the widely popular single leg RDLs, Zercher good mornings, and DB RDLs. Opportunity for variation lies not just in mechanics, but also in the speed of application, which give us plenty of combinations to experiment with.

Extreme Duration RDL

I started playing around with extreme duration RDLs, but only lightly loaded with small dumbbells and just plates. Then I started to add barbell variations. This stretch under load is a great way for trainees to really feel their hamstrings contribution on a hinge movement, provided they maintain a solid neutral spine and don’t hang out through their lower back. The difference between this and, say, the supramaximal RDL is that submaximal loading and the total time under tension are usually around 30+ seconds. I’ve found these work well as GPP exercises or as end stage exercises in hamstring rehabilitation.

Band Overspeed Eccentric RDL and Drop Catch RDL

Athletes who operate at high speeds need high-speed hamstrings to match. I usually follow heavy RDL patterns with periods of conventional and then finally overspeed movements, where the athlete actively punches the barbell to the floor either with or without bands. This combination of elastic response and rapid contract relax takes the heavy structural changes we can achieve with supramaximal work and adds a much-needed neural component.

Video 3. The catch of a ballistic RDL is to teach rapid contraction and isn’t a true eccentric overload exercise due to the weight used. Still, it’s a great exercise for many environments outside of speed athletes.

Sumo RDL

The Sumo RDL is the red-headed stepchild and increasingly Insta-famous member of the RDL family. Its wider stance adds a greater adductor element to the movement and obviously places greater stretch on the hamstring. The Sumo RDL also acts as a great remedy to a lot of the technical issues I mentioned earlier in this article—getting trainees to sling their arms between their legs leads to a much more natural feel and intuitiveness to the movement. With a wider stance, this is obviously an accessory for Sumo deadlifters.

Video 4. If the sumo position is suitable for your athletes, it may be a great option. Choose a foot position and width that is in harmony with the anatomy of the athlete.

Snatch Grip RDL

I touched on the snatch grip variant in the last article, but I didn’t explore it fully. The Snatch Grip RDL can be plugged into a program in lieu of the conventional RDL. The movement calls for greater ROM, massive T-spine stability, and strength, so if an athlete lacks the lat, posterior shoulder, trap, and T-spine strength for conventional RDLs, this acts as a great starting point.

There is less total intensity for the lower body because of the limit the upper body tolerance places on the movement. Because of this, it often makes appearances in my in-season programming. With upper body recovery rates being higher, the feel of intensity remains but the total systemic load is lower. It’s great for athletes who like to feel worked, but don’t need or desire the lower body hammering conventional RDLs can dish out.

Video 5. Using a snatch grip can work if you make sure you are careful with barbell racking and try straps if necessary. The snatch grip is a great option for many situations and offers an effective variation for coaches.

While setup and execution are like the conventional RDL, on setup I usually suggest this movement be trained on blocks or catchers. That’s because the J hooks on racks can interfere with snatch grip setup if you go from a top-down setup and subsequently try and return the bar to the catchers.

Making the Most of the RDL

I’ve been coaching long enough to understand the flaw in being attached to any exercise, but with attachment comes the potential for greater understanding of the nuances. The RDL was something I was taught before I saw the modern nomenclature of the “hinge” make its appearance—what is old is new again. I remember being at a seminar with a well-known coach demonstrating his “hinge” principles and I remarked that it was just an RDL. Sure, “hinge” is a snappier name, but we are really just arguing semantics.

I’ve been coaching long enough to understand the flaw in being attached to any exercise, but with attachment comes the potential for greater understanding of the nuances, says @WSWayland. Share on XMy interest only grew when I made the jump into triphasic training and started exploring it more deeply through various mode of contraction. Hopefully, some of these ideas I laid out can help you make the most of the humble RDL. Just make sure you match the athlete’s competencies to the method, and the RDL can be an enduring staple of their training for a long time to come.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]