What do faster stride frequency and more powerful foot strikes in sprinting have to do with relaxation? It turns out, a lot.

Excess muscle tension is a barrier to optimal performance. In Relax and Win (1981), Bud Winter describes his involvement in a Navy research project to determine why aviators froze under stress. Besides helping our military preserve “Truth, Justice, and the American Way,” Winter would later apply his relaxation techniques to 27 Olympians, three of whom won Olympic gold.

(lead photo courtesy of Washington State Athletics)

Winter believed that athletes should not expend more than 90% effort when they sprinted. He said the additional 10% effort caused unnecessary muscles to fire, slowing them down. An analogy would be trying to drive a car by stepping on the gas and the brake at the same time.

Winter said that coaches should give their athletes cues to relax their jaw, forehead, and hands to avoid excess tension during sprinting. Among his commands were “Run fast, stay loose,” “Get the wrinkles out of your forehead,” and “Drop those shoulders.”

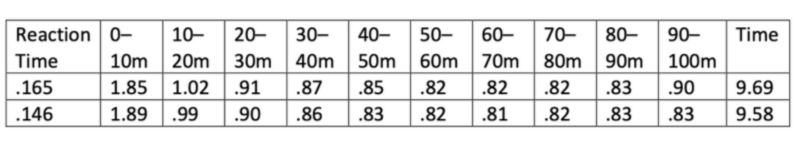

One example of the power of relaxation was Usain Bolt’s splits in the finals of the 2008 Olympics and 2009 World Championships, as follows:

At 70 meters in Beijing, Bolt opened his arms and started pounding his chest in celebration. However, by keeping his upper body relaxed, he maintained splits of .82 and .83 during the next 20 meters and broke the world record with 9.69 seconds. In 2009, he skipped the in-race celebration but ran identical 70m and 80m splits to run 9.58, a world record that still stands.

Gabriel Mvumvure embraced this concept of managing tension during sprinting. Mvumvure competed in the 2016 Olympics in the 100m, representing Zimbabwe. He coached at LSU, Brown, and now at Washington State. Expanding on Winter’s ideas, Mvumvure said sprinters can overstride or become unstable if they expend 100% effort, factors that not only slow them down but increase their risk of injury. These are common faults with high school sprinters trying to achieve the fastest times to impress college scouts.

Mvumvure says he must spend considerable time teaching incoming freshmen how to avoid “tightening up” during a race. He works with them on meditation techniques to help them deal with stress, emphasizes the importance of getting a good night’s sleep, and teaches them how to avoid the “adrenaline dump” that causes so many young sprinters to freeze just before a race. (By the way, in his first year at Washington State, Mvumvure’s sprinters and hurdlers broke 108 personal bests. This year, his athletes broke six school records in the indoor season.)

Relaxation is essential to minimize deceleration during a race and transition from maximum acceleration into maximum velocity. Although Winter’s clues are valuable, many track drills can help an athlete learn how to achieve a balance between maximum force production and a high level of relaxation. Let’s look at three of these drills taught by Coach Mvumvure.

The Right Track to Relax

Mvumvure’s on-track approach to maximum velocity contains three progressive drills (see video 1 below). His athletes perform multiple reps in each drill, mastering the first and then the second before finishing with the third. Each drill involves a drive phase, a transition phase, and a maximum velocity phase.

Relaxation Drill #1

The first sequence has the athlete starting with a longer-than-normal stride length. For every segment after that, they must increase their frequency but shorten their stride. “The more frequency they add, the less I want them to strain,” says Mvumvure.

Relaxation Drill #2

The second sequence is the opposite of the first in terms of stride length. “The athlete starts with a shorter-than-normal stride, which calls for even more frequency because the stride is short,” says Mvumvure. “However, with every rep, they have to open their stride more without changing the frequency they started with.”

Relaxation Drill #3

The final sequence combines the skills practiced in the first two drills: The drive phase stride is long but not too long, and the stride frequency is high. “This sequence provides continuity in acceleration but not to the point where we are just spinning our wheels,” says Mvumvure. “As they enter the transition and maximum velocity phases, the stride length increases while frequency decreases.”

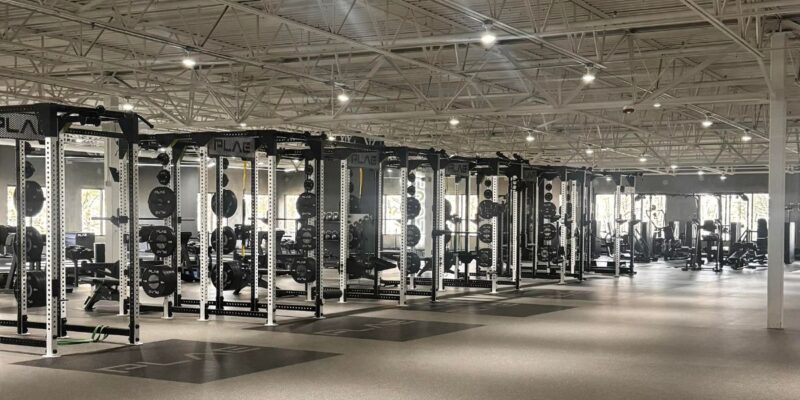

Mvumvure says he often likes to perform these sequences under load, having them wear 7–10-pound vests called speed builders. “Using equipment like the 1080 Motion is also good, but we don’t have the budget. Sleds would be a good improvisational tool if their weight is less than 10% of the athlete’s body weight.”

Video 1. A workout performed by Washington State athletes that includes three drills to teach them to avoid excess tension as they sprint.

Now, let’s look at what to do—and what not to do—in the weight room.

Understanding the Iron Game

The first step to developing an optimal weight training program for sprinting and other high-velocity sports is avoiding methods that create unnatural movement patterns. The Russians were pioneers in this field, conducting extensive research on the role of relaxation in sports techniques over a half-century ago. One of the key researchers in this field was Leonid P. Matveyev, a sports scientist often referenced in strength coaching papers and textbooks for his work on periodization.

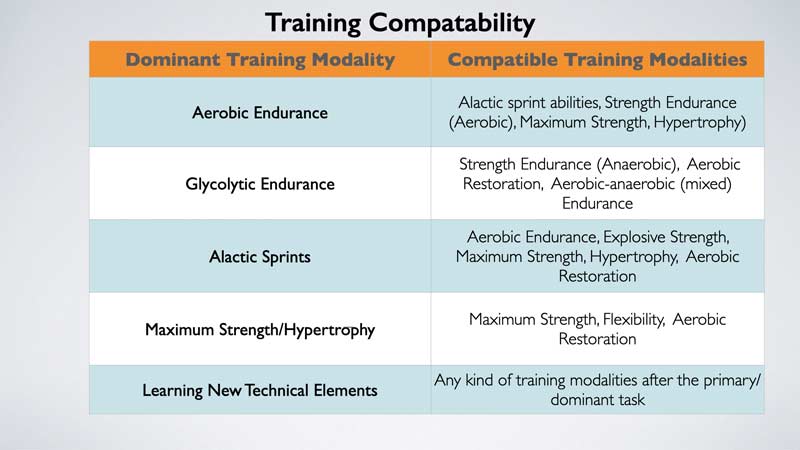

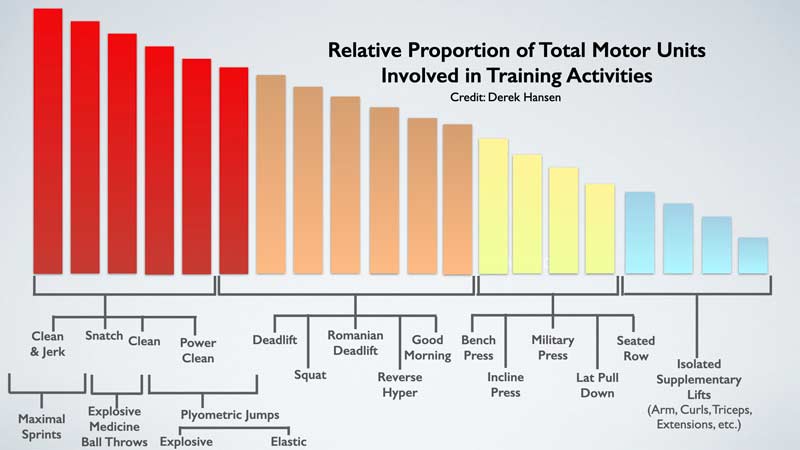

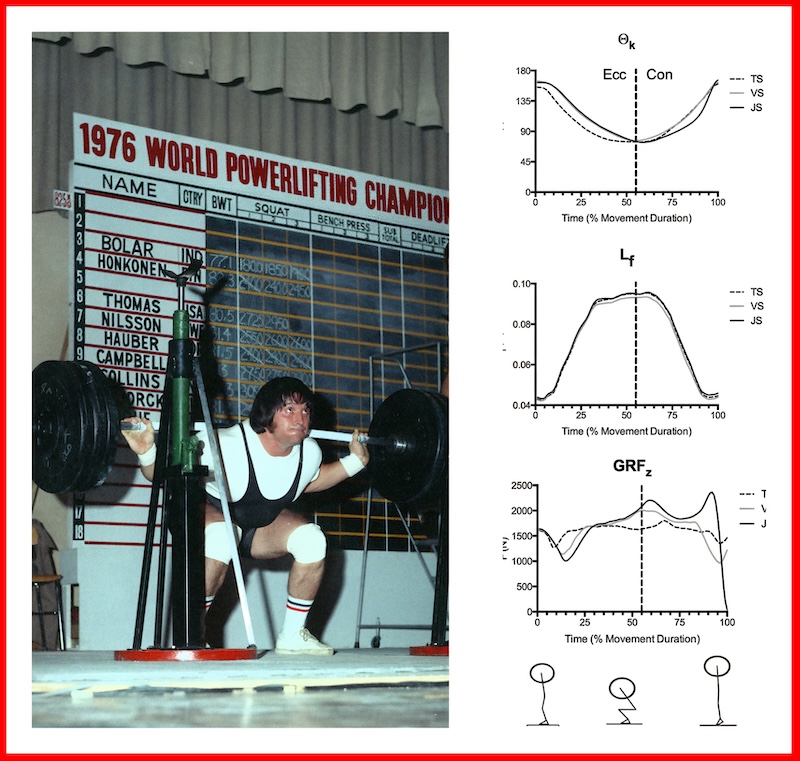

The first step to developing an optimal weight training program for sprinting and other high-velocity sports is avoiding methods that create unnatural movement patterns. Share on XMatveyev said the ability to relax muscles quickly, particularly after a maximal contraction, is a crucial indicator of movement efficiency. It follows that athletes in high-velocity sports should avoid focusing solely on exercises performed relatively slowly and that do not require the muscles to relax quickly, such as deadlifts or bench presses. Here are the three iron game sports that have minimal value to sprinters:

- Strongman

- Powerlifting

- Bodybuilding

These sports produce a high degree of mechanical tension over a prolonged period. Strongman and powerlifting use the heaviest weights for relatively low reps (often 3–5 reps). Further, they create considerable internal tension to provide stability for performing the three competition power lifts and the strongman events, such as lifting heavy Atlas stones.

The issue here is that lifting the heaviest weights and objects in strongman requires relatively slow movements, as there is an inverse relationship between mechanical tension and velocity. Such training also changes how tendons function.

According to a 2013 study in the European Journal of Applied Physiology on the squat, the tendons “act as a power amplifier at light loads and a more rigid force transducer at heavy loads.” As this relates to sprinting, a rigid tendon would not perform like a powerful spring to assist with force production in increasing stride length. Further, Russian sports scientist A. I. Falameyev said that workouts using this type of muscle contraction can negatively influence joint mobility and the elasticity of the muscles and tendons. This has implications from an injury perspective.

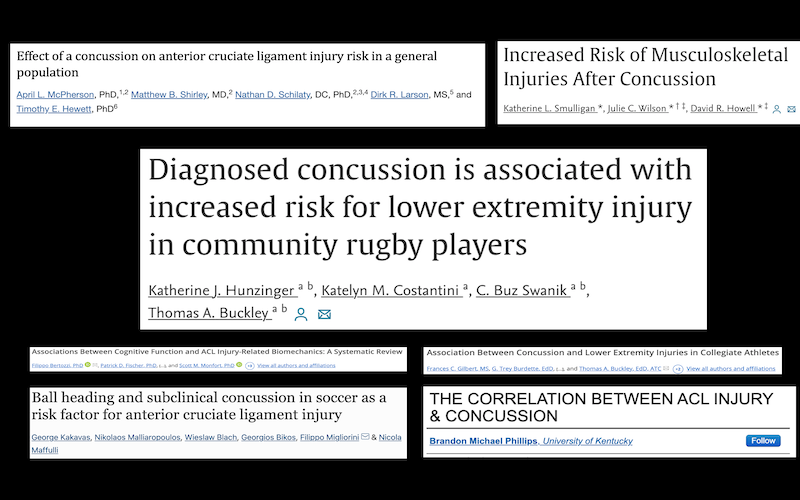

If the majority of your training is devoted to slow movements that make the tendons rigid, it follows that this would be the dominant response in other athletic movements. If an athlete makes a sharp cut on the basketball court or gridiron, and the tendons of the lower extremities don’t flex, something will probably tear. As evidence, consider that approximately 70% of knee and ankle injuries are non-contact.

The Bodybuilding Problem

While the training methods of powerlifters and strongmen apparently may have little transfer to sprinting, bodybuilding methods are worse.

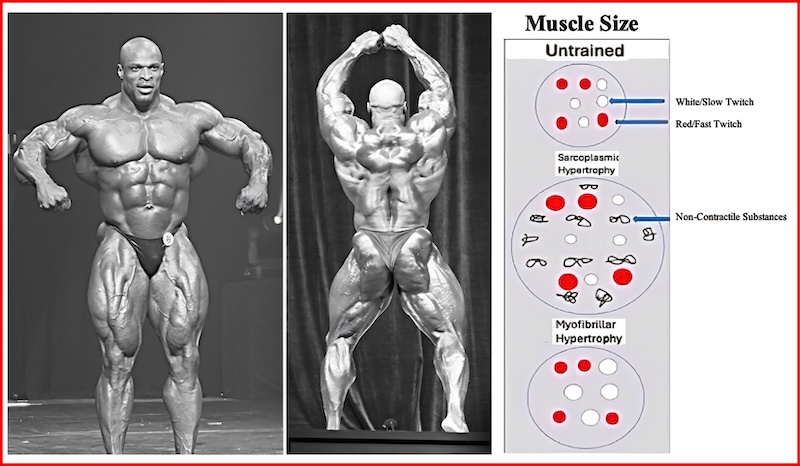

Let’s start by distinguishing the two types of hypertrophy: myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic. Myofibrillar hypertrophy primarily increases the size of muscle fibers. Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy also involves the development of components that add size to the muscle but do not contribute to force production (see image 5 below).

In a 2002 paper, Russian sports scientist Igor Abramovsky warned that weightlifters must be careful about increasing their body weight because it “…creates additional loading on the sportsman’s muscles because the weightlifter has to lift this excess weight during the execution of the weightlifting exercises; second, the sportsman’s speed deteriorates.” Sprinters must consider the stress the extra body weight puts on the cardiovascular system, which becomes a significant issue in distances over 100 meters. There’s more.

Training methods that develop myofibrillar hypertrophy usually develop the powerful fast-twitch muscle fibers, whereas sarcoplasmic hypertrophy primarily works the weaker slow-twitch muscle fibers. Power production is further inhibited because such training affects the ability of the muscles to contract rapidly.

A study published in Experimental Physiology in 2015 concluded that bodybuilding methods affected the ability of the athlete to create maximal muscle tension. The researchers said that compared to power athletes (such as weightlifters and sprinters), bodybuilding training may be “detrimental to increasing muscle fiber quality.”

Finally, hypertrophy affects the pennation angle of the muscles, which refers to how the contractile components of muscle fibers are organized. Hypertrophy changes the pennation angle of the fibers in relation to the tendons they are attached to, making them less efficient at producing force.

The takeaway is that bodybuilding protocols focusing on sarcoplasmic hypertrophy should be avoided if sprinting speed is a priority. But that doesn’t mean using ultralight weights on bodybuilding exercises or partial-range movements.

Not to single out anyone, but I’ve seen many published workouts by sprint coaches who attempt to avoid bulking up their athletes by using light weights for high reps. In one published workout designed for high school sprinters, the highest percentage for cleans was 50%–60% of the one-repetition maximum, so about half of the athlete’s maximum result. He increased the percentages to 70%–80% for squats. For college sprinters, he increased the clean percentage to 70% and the squat to 85%, although the reps stayed the same.

Although using light weights may avoid developing significant levels of muscle bulk, they do not create enough mechanical tension to increase an athlete’s ability to produce force significantly. Share on XAlthough using light weights may avoid developing significant levels of muscle bulk, they do not create enough mechanical tension to increase an athlete’s ability to produce force significantly. For example, in looking at weightlifting workouts published in their journals, the Russians often did not list sets of under 70% of an athlete’s maximum. Why? Because these percentages did not generate enough muscle tension to stimulate increases in strength or power—they were considered warm-ups.

This is not to say that weight training protocols designed to develop absolute strength or hypertrophy should never be performed but that they should not comprise the majority of time spent in strength and conditioning programs. With that warning, what are the alternatives? Let’s take a look.

The Pulsating Athlete

Stuart McGill described sprinters and competitive weightlifters as “pulse” athletes, meaning their muscles contract quickly and then relax completely in a pulsating fashion. Weightlifting sports scientist Bud Charniga would agree.

“The weightlifter’s muscles rapidly alternate muscle tension (agonists) with muscle relaxation (antagonists),” says Charniga. “A state of constant tension/relaxation during the classic exercises is punctuated by very fast switching between extensor muscles such as quadriceps, and flexors (hamstrings, anterior tibialis) from maximum tension to maximum relaxation.”

Note that Charniga said the “classic exercises,” which are the snatch and the clean and jerk, work the muscles through a large range of motion, in contrast to the powerlifts. He did not say hang power cleans, and he has been an outspoken critic of these and other so-called “weightlifting derivatives.” Charniga says these exercises do not match the tension/relaxation patterns of the full lifts.

Of course, many college strength coaches do not know how to teach the full lifts. If they are serious about learning them, they should consider getting together with a weightlifting coach who can at least teach them to perform a full clean. In the meantime, or as an alternative, they could have their athletes perform many relatively simple dynamic jump exercises in the weight room that follow the contraction/relaxation patterns in sprinting. Video 2 shows two examples of such exercises.

Video 2. The assisted squat jump and the barbell squat jump follow the contraction/relaxation patterns used in high-velocity activities such as sprinting.

Many strength coaches use bands that prolong the concentric contraction of lifts, such as the squat, deadlift, or bench press. This is not a good idea. This contraction/relaxation pattern is different from what occurs in sprinting. “An analogy would be running only uphill, where the force remains constant,” says strength coach and posturologist Paul Gagné.

Along with the classical weightlifting exercises and squat jumps, a better alternative would be isoinertial training using flywheel devices. “Iso-inertial training more closely matches human movement patterns in dynamic sports,” says Gagné. “It also provides fast eccentric overload. An analogy would be running on a level surface and transitioning into running downhill, then repeating the sequence to create a cyclic effect.”

Not having the strength to control eccentric movements in sports is believed to increase an athlete’s risk of injury, as evidenced by the statistic I mentioned earlier that an estimated 70% of knee and ankle injuries are non-contact. Because women are at a much greater risk of developing knee injuries than men, it follows they should make fast eccentric training a priority. Flywheel training is ideal for eccentric overload because the harder you push or pull, the more eccentric overload is produced.

A word about kettlebells. Kettlebell swings involve dynamic movements that improve the timing between rapid eccentric and concentric muscular contractions, so that’s good. However, providing overload with stronger athletes is challenging (and few gyms have heavier pods), so they should be reserved for warm-ups in most cases.

Sprinters and other athletes in high-velocity dynamic sports should use training methods that focus on providing powerful muscular bursts followed by prolonged relaxation. Share on X

The bottom line is that sprinters and other athletes in high-velocity dynamic sports should rarely use methods that primarily develop maximum strength or muscle bulk, like those used by bodybuilders or powerlifters. Instead, they should use training methods that focus on providing powerful muscular bursts followed by prolonged relaxation. As Bud Winter would say, “Relax and win!”

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Winter, Bud. Relax and Win. Oak Tree Publications, 1981.

Lee, Jimson. “Usain Bolt 10 Meter Splits, Fastest Top Speed, 2008 vs. 2009.” SpeedEndurance.com. August 19, 2009.

Charniga, Andrew, Jr. “The Secret to the Weightlifter’s Strength: Speed of Muscle Relaxation.” Sportivnypress.com. January 30, 2023.

Earp JE, Newton RU, Cormie P, and Blazevich AJ. “The influence of loading intensity on muscle-tendon unit behavior during maximal knee extensor stretch shortening cycle exercise.” European Journal of Applied Physiology. October 2013.

Earp JE, Newton RU, Cormie P, and Blazevich AJ. “Faster Movement Speed Results in Greater Tendon Strain during the Loaded Squat Exercise.” Frontiers in Physiology. August 20, 2016.

Charniga, Andrew, Jr. “Achilles Tendon Ruptures and the NFL.” Sportivnypress.com. February 9, 2017.

Gagné P and Goss, K. Get Stronger, Not Bigger. 2021:113–117.

Abramovsky, Igor. “A Weightlifter’s Excess Bodyweight and Sport Results.” Sportivnypress.com, Bud Charniga Translation: May 2, 2014 (Originally published in 2002).

Meijer JP, Jaspers RT, Rittweger J, Seynnes OR, Kamandulis S, Brazaitis M, et al. “Single muscle fibre contractile properties differ between body-builders, power athletes and control subjects.” Experimental Physiology. November 2015;100(11):1331–41.

McGill, Stuart. “An Approach to Pain-Free Training for Track Athletes with Stuart McGill.” SimpliFaster. December 2023.

Lyons, Todd. Personal communication, March 13, 2024.

Boden BP, Dean GS, Feagin JA Jr, and Garrett WE Jr. “Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury.” Orthopedics. June 2000;23(6):573–578.