[mashshare]

The visitors that come to ALTIS for our Apprentice Coach Program arrive from all over the world and have experiences across a multitude of sporting environments. Despite their wide range of roles, levels, and sports, one of the most widely shared problems revolves around a common question: Who should we allow in our training environment, and what traits should we look for in new coaches and athletes?

To begin with, we must ensure there is shared understanding around the variability of environment. Without a doubt, each high-performance setting is different. Therefore, we cannot all share the same prerequisites for introducing new individuals. With this, it is important to identify and truly understand the environment you are part of in order to have any hope of facilitating a successful culture.

This is a very important aspect of the way we operate at ALTIS. As mentioned in a previous article, people make all the difference. When looking to establish a high-performance environment, getting the right people on board is vitally important.

In the past, we have had athletes come train with us who seem to think I’ve made it into a professional setting—now all I need to do is passively follow along and success will come. This is not the case! Both the staff and athlete populations must assume an active role. Furthermore, an openness to expressing vulnerability will enhance the coach-athlete-therapist partnership and can serve as a foundation for success.

An openness to expressing vulnerability will enhance the coach-athlete-therapist partnership and can serve as a foundation for success, says @jhettler24. Share on XFor this to happen, a few key pieces must be in place. First and foremost, group-wide critical thinking and the constructive challenging of ideas must be a well-accepted practice within the performance environment. As individuals, we should take the onus upon ourselves to build a case that supports our ideas. We must accept the “burden of proof.” From there, we can embrace the positive effect that comes from directed conversation.

A diversified and trusted network can be extremely helpful in this context, as can social media when used constructively. Further, exposing yourself to contrarian thought can help you avoid the dangers of groupthink within your environment.

Collaboration is evident in everything that we do and seeking the help of those around us—both internally and externally—is standard operating procedure. As individuals, we will never have all of the answers; as a team, however, we can compile our collective knowledge and find guidance in any situation.

We can relate this concept of vulnerability to the human body as well. From neuroplasticity to allostasis, processes are in place that allow us, through information sharing and the pooling of resources, to adapt and thrive in the face of threats and stressors. We are vulnerable beings that possess the ability to reach new heights when challenged.

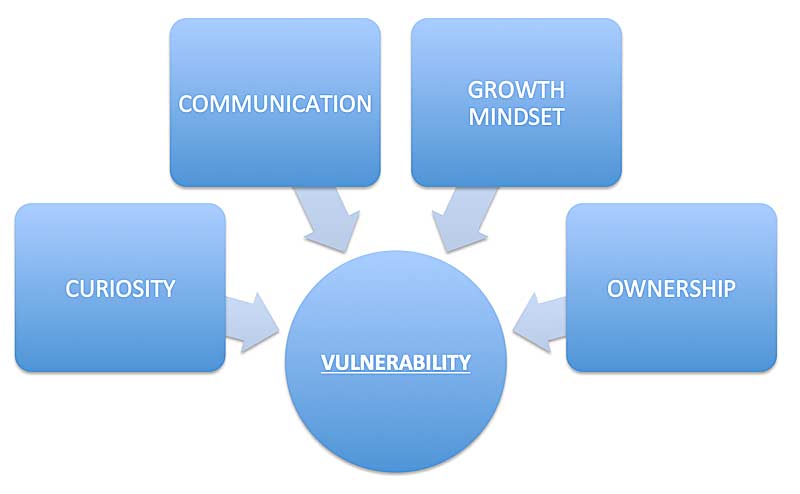

Without further ado, the following character traits that lead to success in our environment branch off from this idea of shared vulnerability.

Curiosity

Curiosity—as an admission of not knowing something—is closely linked to vulnerability. When all parties involved are in search of a greater understanding of the training process, learning is expedited. Athletes who are curious, ask questions, and seek to understand ultimately hold us accountable as coaches.

Coach Dan Pfaff often talks about athletes obtaining a “Ph.D. level knowledge” of their event or sport. Familiarity with past and current performers, noting trends and patterns over time, and becoming a mindful consumer of therapeutic inputs are but a few of the topic areas within this curriculum.

A number of training camp athletes go through ALTIS each year, and it becomes quite clear fairly early on which of these athletes come from a curiosity-rich environment and are open to expressing their personal vulnerability. These camps are often only a few weeks in duration, and while plenty of worthwhile progress can be made in that time, it is the curious athletes that make the most of their time with us and increase their likelihood of sustained, long-term progress.

The not-so-curious athlete usually has insecurities about their knowledge and abilities. This limits their progress, as we now have to spend valuable time attempting to gain a greater contextual understanding of this unique puzzle. Competency often comes with curiosity, and as the shared knowledge increases, the likelihood of deep and meaningful conversations increases. More and more pieces to the training puzzle then become available.

As coaches and therapists, we can benefit in our personal development by working alongside curious athletes, says jhettler24. Share on XAs coaches and therapists, we can also benefit in our personal development by working alongside curious athletes. Their perspective can often lead to questions that we may not have considered previously, forcing us into the critical thinking habits previously discussed.

Curiosity can show itself in more ways than one. In addition to the more obvious verbal manifestation—rooted in questioning and answering—some athletes may gravitate more toward a movement-based expression of their curiosity. This often occurs through play.

I have seen many examples of this form of curiosity expressed within Coach Andreas Behm’s group of hurdlers. At times throughout the training year, he employs what he calls “Freestyle Friday.” This is a designated training time for the athletes to act on their curiosity and allow a creative outlet for exploration. For Coach Behm, it provides insight into the athlete’s mind, giving clues to what drives them or where they believe their weaknesses are.

Bringing it back to vulnerability, in this instance Coach Behm is expressing vulnerability by admitting to not having all of the answers. Allowing the athletes to take ownership of their “Freestyle Friday” training session can be risky at times (more on this to come), but in the appropriate environment, with the appropriate people, it can be a valuable tool.

Communication/Reporting

Curiosity can only lead to improved discussions if communication and reporting abilities are also available. When an athlete develops competency and can effectively communicate and report, the coach-athlete relationship is able to reach new heights. Conversation is the glue that brings together the visual abilities of the coach and the perceptual abilities of the athlete.

No one entity has all the solutions to the training process, but through teamwork we can bring life to the saying, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” Unfortunately, many athletes have a tendency to withhold valuable information revolving around fear of failure, injuries, personal matters, and more. If vulnerability is expressed by all parties involved, we can open the way for more straightforward and informative communication.

One way in which we, as coaches, can facilitate vulnerability through communication and reporting is by being creative with our “Plan B” sessions. Many athletes feel they need to complete everything that is written on their program in order to improve. We can combat that by assuring them that we will prescribe an appropriate session based on their current state that keeps them as close to “Plan A” as possible.

Early detection and early response are key components of the ALTIS Performance Therapy Methodology, but this is stunted when there is a breakdown in the communication and reporting.

For instance, athletes will often withhold pain-related information when they feel they can manage it on their own. They may be able to get away with this for a short period of time, but too often these occurrences—when not detected and managed on the front end—spiral into something more serious. Whereas an initial management strategy may be a slight reduction in load or a shift in training elements, the strategy then must turn toward something more drastic, such as missed training or competition.

If the athlete population knows that they can openly express their state of readiness and still complete worthwhile training sessions, the entire process becomes enhanced.

Growth Mindset

Popularized by Carol Dweck, the term growth mindset suggests that abilities such as intelligence can be developed through:

- Embracing challenges and obstacles

- Putting forth effort

- Remaining open to criticism and failure.

In opposition to this, a fixed mindset avoids all of these mechanisms for advancement and views abilities like intelligence as static.

In our setting, a growth mindset is a necessity for many reasons. The most glaring may be the openness to criticism and failure that accompanies such a mindset. The journey to, and the navigation of, elite sport is filled with defeat, both in training and competition. Identifying these circumstances as opportunities for growth (as opposed to signs of inadequacy) will lead to greater fulfillment.

Additionally, those who possess a growth mindset will often find it easier to share their vulnerabilities. Recognizing that advancement is possible leads to a greater willingness to accept the help of those around us.

As the Internship Coordinator at ALTIS, I see many young professionals who struggle to learn from mistakes and failures. Similar to the athletes who have insecurities around their knowledge and abilities—and therefore struggle to express curiosity—these young professionals with a fixed mindset will often construct a post-hoc narrative that prevents their growth. They then enter a state of stagnation and continue to do things the way they have always done them. Their biases blind them to learning and growing.

Disclaimer: While a growth mindset can be a great tool, it is important to note that it is not a holy grail. Putting forth the appropriate effort is key to athletic achievement and something that should be recognized—but when it comes down to it, we are in the business of outcome more than process. At times, genetic predisposition may favor more heavily than effort in the outcome. Therefore, we must respect the role of each!

Ownership

With ownership comes responsibility. When we can share this with our athletes, there is a mutual understanding that each party will do everything they can to effectively control what they can control. There is no blame. There is no finger-pointing.

One way to help facilitate ownership in competent athlete populations is to provide them with autonomy within their training programs. Including programming ranges and options in the training plan allows athletes to fill in the gaps and can lead to greater buy-in and collaboration.

Including programming ranges and options in the training plan allows athletes to fill in the gaps and can lead to greater buy-in and collaboration, says @jhettler24. Share on XCeding this control can be difficult at first, but as Willink and Babin state in their book Extreme Ownership, “Discipline equals freedom.” If we exhibit the discipline to educate the athlete population on how our philosophy fits within the training process, and if the athletes have the discipline to develop their own understanding of this, both parties will experience the freedom of shared ownership.

One example of this that we consistently use at ALTIS is giving the athletes the option of squats or deadlifts when targeting the development of maximal strength during the competitive season. This ensures the athletes take ownership of their program through a crucial time of year: The competitive season.

Further, Dan Pfaff’s “Rollover Cycles” breed ownership and autonomy with the athletes, as they are very much in control of the density of training when these programs are employed. This becomes particularly useful during times of travel and competition, as schedules can quickly become chaotic and the inability to predict adaptation is even greater.

The competitive season is effective in highlighting which athletes are comfortable taking ownership, particularly in individual sports. In some cases, support staff are not always present at each and every competition. When this is the case, the athletes have two options: Take ownership of the situation or make excuses.

Ownership of the process will bleed into ownership of the outcome. If we can all look internally when things don’t go according to plan and have constructive conversations, the puzzle will become clearer.

Putting It All Together

I realize not everyone who reads this will be in a position to control who is included or excluded from their environment. It is these cases that require an attempt to foster the necessary character traits for success.

The responsibility held by those who have control over the athletes to whom the doors to a team/organization are opened or closed should not to be taken lightly. They must dedicate time to recognizing the current state and future direction of the team/organization and then identifying the character traits that will lead to both success and failure.

Furthermore, once the steps have been taken, it is essential that the findings are used to guide decision-making. Exceptions cannot be made for “special circumstances,” as this will only introduce toxicity into the culture and the disruption will inevitably be profound. The phrase, “It’s not what you preach but what you tolerate,” (again from the book Extreme Ownership) is applicable here.

Ultimately, the culture we create is a product of what we tolerate, says @jhettler24. Share on XUltimately, the culture we create is a product of what we tolerate. As leaders, the standards we set must be upheld; otherwise, we run the risk of losing control.

For athletes, expressing curiosity and being diligent with communication and reporting will help you to achieve a growth mindset and find the freedom that comes with taking ownership. As coaches, it is our responsibility to orchestrate the utilization of these pieces to create a masterpiece.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

2 comments

Kika Mela

Great article and very true. Thank you for posting this

Sahana Kumari

Coach I am Sahana Kumari Olympian high jumper women’s national record holder 1.92,i sm visiting New York for some work so can it possible to meet u in university an discuss little knowledge thing