Let me set the stage for you: A 6-foot, 200-pound Division I athlete walks into the gym. Their body is chiseled from granite, like Michelangelo’s David. They exude confidence as they walk across the turf to introduce themselves to you with a soul-crushing handshake. And then this elite athlete—we’ll say they’re an ice hockey player—gets to their speed work and sprints 15 yards. To your disbelief, their elbows are askew, their knee drive is minimal, and their pelvis is tilted so far anterior it’s as if they’re defying gravity to just stay on their feet.

In other words, this future NHL draft pick’s sprint technique is a hot mess. However, while their technique isn’t strong, they are an explosive, powerful athlete. You don’t want to interfere with their skate stride, but a few easy cues can clear up some of their technical deficiencies in sprinting. As their strength and conditioning coach, you can now take two approaches:

- Drill their sprint work to perfection.

- Embrace the mindset of Wabi Sabi.

Per Adam Grant’s book Hidden Potentials, Wabi Sabi is the “art of honoring the beauty in imperfection” (p. 69). However, as strength and conditioning coaches, we far too often focus on getting every lift or sprint exactly right, seeking perfection at the cost of the athlete’s confidence or moving on to other aspects of developing them as a holistic athlete.

There is a law of diminishing returns where coaches can over-coach an athlete out of their natural flow state, thus hindering their performance and development along the way, says @CoachDottavio. Share on XI do believe in the A-B-C phrase “always be coaching,” but there is a law of diminishing returns where coaches can over-coach an athlete out of their natural flow state, thus hindering their performance and development along the way.

Wabi Sabi vs. Perfection in Team Sports

If coaches chase perfection, we eliminate the Patrick Mahomeses of the world. Looking for perfection over Wabi Sabi is a major flaw in both scouting and coaching. “Mahomes Magic” is fueled by the funny way the Super Bowl MVP trots around the field between plays and the off-platform throws he has become so famous for—far from perfection, but dang, he’s good!

In baseball, some of the game’s best players have done things differently. Mariano Rivera abandoned the full wind-up for the exclusive use of the stretch. Tim Wakefield hung around baseball for 19 major league seasons, relying on his unpredictable knuckleball. And Gary Sheffield’s iconic “bat wave” was one of a kind at the plate.

Yet, when it comes to speed training, many team sport and S&C coaches feel the need to cram every athlete into a 100-meter sprinter’s box. A famous Wabi Sabi phrase is “perfectly acceptable,” and the sprint techniques of team sport athletes are perfectly fine to fall into that category.

Soccer players like Lauryn (above) need max velocity sprinting in their programming, but does their sprint technique need total refining, or should they take a Wabi Sabi approach of making small changes until they’re good enough? Some easy changes I typically refine with her are staying loose as opposed to neck tight and keeping her hands like knives instead of fists. That’s the balance between detailed coaching and perfectionism.

When is a team sport athlete’s sprinting form good enough? Per Hidden Potentials, perfectionists get it wrong in three areas:

- They obsess over moot details.

- They avoid unfamiliar and difficult tasks.

- They berate themselves over mistakes.

Our perfectionists don’t master problem-solving, they don’t embrace discomfort, and they can’t hang loose.

In the article “Optimal Strategies for Improving Football Speed,” Dr. Matt Rhea said, “Field sport movement mechanics are very different from track sprint mechanics.” Think about it: the start is different, and then the need for deceleration and change of direction, the impact of visual stimuli and reaction, and the presence of decision-making and contact are key parts of sport that aren’t parts of the 100-meter dash.

At EB Athletics, our intake assessment for new clients includes a 10-yard fly with a 5-yard lead. Not only do we time their mini fly 10 on a Freelap Timing System, but I evaluate and make notes about their sprint technique. If there are drastic flaws, yes, we’ll work to improve in those areas. But I’m not going to attempt to turn a team sport athlete into a perfect Olympic-level 100-meter sprinter or even 400-meter sprinter.

There are a few key points I look for in a non-track sprint that were taught to me by speed coach Dale Baskett (Athletic Speed and Movement): starting stance (gait, posture), arm angles, eyes, and hands. As coaches, we can use one-word cues to address each: “Gait,” “L’s,” “Knives,” and “Eyes.” With another Wabi Sabi mindset being “less is more,” those one-word coaching points elicit an immediate correction from the athlete without overloading them with too many corrections or too many words.

Most of our younger athletes first need to focus on increasing their strength while improving their coordination. With improved strength and coordination and a dose of sprint “drills,” we will see improved form. Athletes brand-new to training see the most immediate gains and are typically more open to trying new things because everything about the S&C experience is new.

One Step Back to Take Two Steps Forward

One area of concern for many experienced athletes is that they have to accept potentially getting slower before they get faster. If you’ve ever switched from the hunt-and-peck method of typing to the touch-typing method, your typing speed slowed down at first. However, your ceiling was far higher once you learned to touch type.

Sprinting, much like learning any new skill, works the same way. As Dr. Art Markman said in his piece “People Can Learn to Appreciate the Discomfort of Learning” for Psychology Today, “Just because something feels uncomfortable, though, doesn’t mean that it is bad for you.”

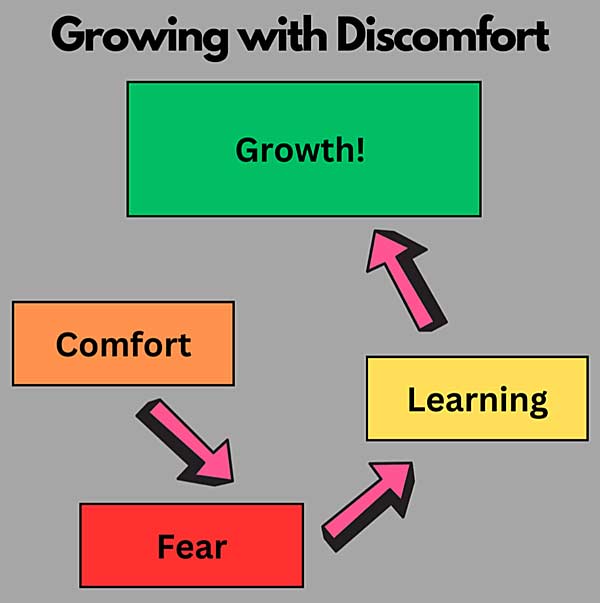

As you can see in the “comfort zone” image above, athletes must push from comfort to fear to learning before they can grow. To become better at their sport, the athlete will have to push away from using their standard, anxiety-free skills to use a new set of skills that are still in the learning process.

In her appearance on the Coachspeak podcast (Season 1, Episode 9), soccer strength and conditioning coach Erica Suter said, “You can’t get confident if you’re not challenged. If everything were easy, would you get better at all?” Suter also identifies the need to play multiple sports and have time for free play in order to build confidence as an athlete at an early training age.

For an athlete learning a new skill or technique not to feel defeated, Wabi Sabi can serve as a great mental approach to growth. An athlete expecting perfection on their first sprint using a new technique would be setting too unreasonable of a standard. Standards and goals should be set appropriately with the right difficulty but not entirely out of reach. Expecting that sprint to be perfectly acceptable rather than perfect will push the athlete from comfort into growth.

Wabi Sabi embraces natural flaws without trying to create them purposely, so when you expect a sprint to be perfectly acceptable rather than perfect, it pushes an athlete from comfort into growth. Share on XAs a coach, it’s okay to fix one thing at a time. Just like when people need to quit smoking or change their eating habits, a wholesale diet switch—or going cold turkey—is an option that works for very few people. That’s why the Wabi Sabi approach to sprint technique is a good option: Wabi Sabi stays neutral rather than risking being overly positive (“You will get faster!”) or potentially devastated (“But I should be perfect at this NOW!”).

Wabi Sabi embraces natural flaws without trying to create them purposely. In a society that focuses far too much on perfect social media filter appearances, Wabi Sabi embraces our beautiful imperfections as humans. That blemish, scar, or tight curl is part of our beautiful imperfection. The same goes for sprint technique with team sport athletes. That slight hand turn or head bob is okay as long as it won’t injure the athlete.

Let’s consider the difference between a track sprinter’s arm angles and action and a soccer player’s. A soccer player opens and closes their arm angles less and more rarely achieves an ideal upright sprint technique because they constantly need to decelerate and change direction. Of course, we won’t program sloppily or allow a sprinting technique that will clearly lead to injury. We work slowly and methodically to correct while keeping the athlete engaged and our mindsets in neutral.

The Freelap Timing System combined with the approach that track and field coach Tony Holler promotes—“Record, Rank, Publish”—are the methods I use at our private training facility, EB Athletics (located in Raleigh, North Carolina).

However, one of our favorite metrics is based on growth. While we do keep a leaderboard of our top fly 10 scores, we also keep a growth leaderboard (see above). In the book Hidden Potentials (referenced earlier), Dr. Grant also discusses the need to calculate the rate of improvement over time. In other words, the growth the athlete has seen over time in your training program.

Tracking data is a great way to sell memberships to your gym, no doubt. But it’s even more of a great way to keep athletes pushing forward through the dog days of the off-season and into their school or travel seasons. Pushing against their old self to create a new standard while overcoming the discomfort of growth is a truly intrinsic reward. I may not be the best, but I’m the best me that I’ve ever been, and that’s what really matters for most people!

As coaches, we have to facilitate that desire. The Wabi Sabi approach will help our athletes hang loose, play in a flow state, and accept being perfectly imperfect. Besides, what is success worth if we never get to enjoy it?

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Dottavio, Justin, host. “Erica Suter.” Coachspeak podcast, 2/29/24.

Grant, Adam. Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things. Viking, 2023.

Markman, Art, “People Can Learn to Appreciate the Discomfort of Learning,” Psychology Today, 11/29/22.

Moawad, Trevor. It Takes What It Takes: How to Think Neutrally and Gain Control of Your Life. HarperOne, 2020.

Rhea, Matt, “Optimal strategies for improving football speed,” LinkedIn, 2/23/24.