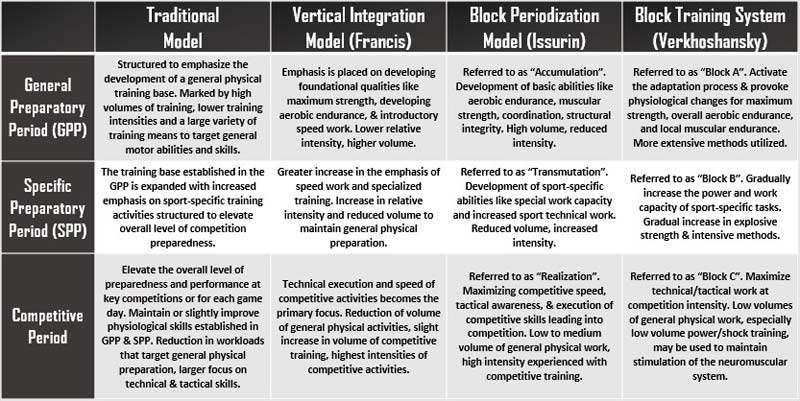

In today’s expanding world of high school sports performance, there are a multitude of tools at our fingertips that can really help our programs stand out. Some of them are technology-related: For instance, velocity-based training devices, online training websites, etc., are all things we can lean on to make our program better. Other ways we can ensure the success of our program are programming-related: APRE, linear periodization, conjugated periodization, cluster sets, and the tier system (just to list a few!). These are all modalities that can fit into programs and, when mastered, help us grow as coaches and ensure the development of our athletes.

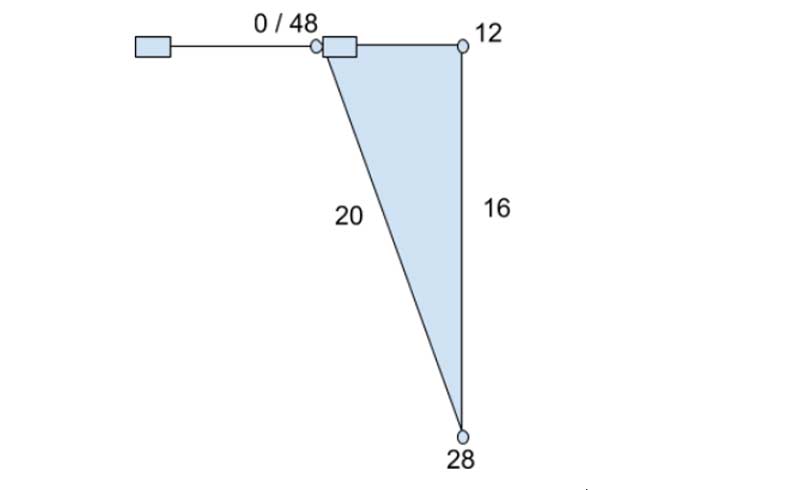

I will discuss my program’s process and the step-by-step approach we use to prepare our young athletes to climb the ladder from our “Block 0” program upward, with the goal of reaching our “Block 4 Elite” level. This is the first of several articles in a series that will provide an in-depth and comprehensive look into the process our athletes go through from the lower grades through the end of their freshman year. I give an overview of the program in this article and will go much more in-depth for each portion in upcoming articles.

Invest in the Future with the Talents of Today

Over the last 22 years, I’ve used or (at the very least) researched just about every one of these things with athletes. Having a growth mindset and embracing and growing from both success and failure is, in my humble opinion, a sign of striving for success in any field.

I’m a big believer in self-reflection and evaluation. When I sit and evaluate the multitude of things we have instituted across the years in our program, one specifically jumps out at me as being probably the most important of all. Having a vertical integration plan for athletes with an evidence-based protocol to transition from the sub-freshman level to the varsity level is, without a doubt, the most impactful addition to our program. It has had a great effect on not only the development of strength, speed, and power, but the overall health and well-being of our athletes.

A vertical integration plan for athletes with an evidence-based protocol to transition from the sub-freshman to the varsity level has been the most impactful addition to our program. Share on XThe way we approach the transition from a little-to-no-experience-level athlete coming to us from middle school to a senior athlete very close to full maturity doesn’t have to be complicated. It does, however, have to be organized and done with purpose. The process can vary by situation. If we have exposure to the athletes at the middle school level or below, it is an even greater advantage and opportunity. Yet, even if you don’t see your athletes until the first day of their freshman year, an organized and purposeful plan will help them reach their full potential.

Buying into the Process of LTAD

The first step in the process of vertical integration of your program is developing a rock-solid and trusting relationship with your sub high-school-level coaches and athletes. Every situation I have been in has been quite different in many ways. One factor that remained the same in all was the eagerness of most lower-level coaches to have me involved in the development of their athletes.

A second factor that was also the same was the excitement of parents and their kids to have the opportunity to be submerged in the coaching and culture that they will experience at the high school level. Most of the time (including my current situation), that eagerness has resulted in not only trust in the process, but an attitude of growth that has led to a smooth transition. If your lower-level coaches embrace a growth mindset and are willing to accept the educational process, there is a great opportunity for excellence.

Building a solid relationship with parents and athletes will also lead to a situation that is conducive to your goals. While that trusting and positive educational working relationship is often an end result, in many cases there are obstacles that must be navigated. The most restrictive of these stems from a lack of experience in actually doing what is best for the young athlete.

My biggest obstacle with all three groups that need to be nurtured is without a doubt the process that many call “slow cooking” athletic development. As we all know and understand, we live in an “instant results” world. This situation is no different. A slow and in-depth process of mastering the ordinary aspects before moving to the next step is absolutely the correct path to take, but it isn’t the one that sells.

Parents can PAY outside coaches who will have their 12-year-old doing the same workout as a 17-year-old. Coaches can seek out high-level programs online that will promise immediate success with little or no attention to the details of actual mastery. The challenge for us lies in building a trust that will convince both groups to allow us to do what we all know is best.

The biggest factor in developing the trust of athletes, parents, and other coaches is being present, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XThe biggest aspect of developing this trust, in my experience, is being present. Reach out to coaches. Learn their process and evaluate what strengths they may already have. The worst thing we can do is walk into a situation (often one that has been that way for many years) and make it seem like they know nothing and do everything wrong. A discouraged coach is that much harder to bring around to your way of doing things.

Once you have a personal relationship started with coaches, they will trust that what you need them to do differently is best practices. Spending time with them in both a co-coaching and teaching/learning environment will bring them into your program much faster than just showing up and demanding change. It’s also very ineffective to simply email a document or program to these coaches. In my experience, much will be lost in translation and very little will be put to use. The bottom line is you need to reach out and build a positive personal relationship first. Once you have that established, the idea of “slow cooking” the process and the skills needed to do so will be embraced and accepted.

Fostering the Trust of Parents and Athletes

The much more difficult job will be selling the idea to parents and athletes. The single biggest issue I have, even in our higher levels, is them accepting and trusting our process. They see athletes doing heavy back squats, jumping on 54” boxes, and doing full Olympic movements and want to do them as well. It’s human nature to want to emulate the people who are already successful. Too often, we don’t realize that the success of those high-level athletes came about because of a process.

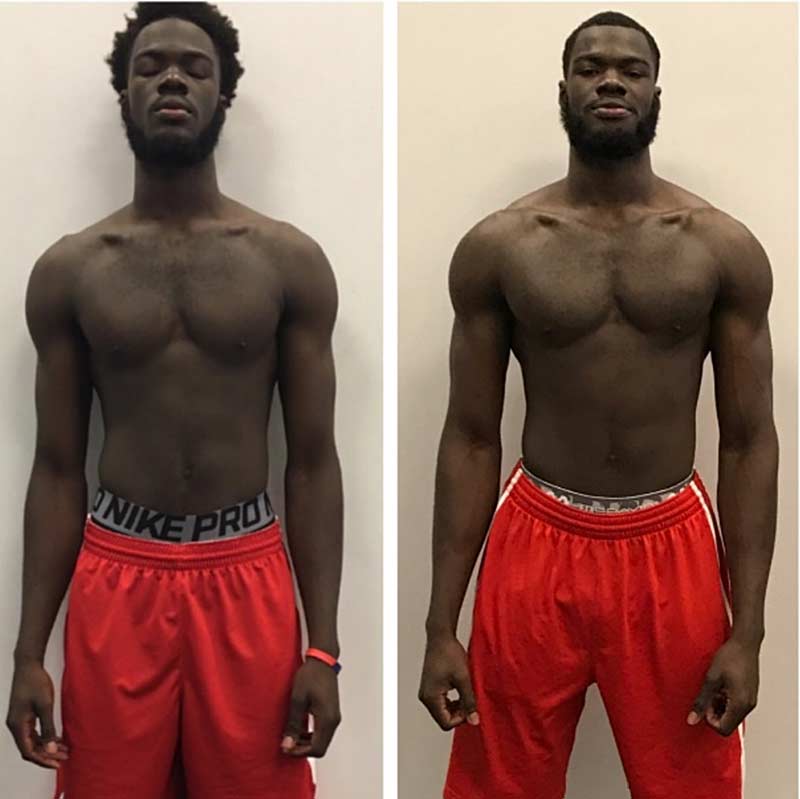

Literally on a daily basis in our program, I have to talk about trusting our process and not resisting our programming because it could be done with heavier weights. Parents often don’t understand how adaptations differ and push a higher volume “bodybuilding” type program. They see hypertrophic results and confuse “big muscles” with powerful and explosive ones. Being strong, powerful, and explosive doesn’t always correlate to muscle size.

Once you build trust, parents and athletes alike will turn to you with questions that will shape their beliefs, and not to an outside source motivated by income, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XAs is the case in many of my articles, I suggest relationship building and education to combat these obstacles early on. The single biggest limiting factor for our athletes is lack of parental knowledge and support for what constitutes a safe and effective sports performance program. It’s our job to foster those relationships as early as possible. Once you build that trust, parents and athletes alike will turn to you with questions that will shape their beliefs, and not to an outside source motivated by income.

What You Allow Is the Standard

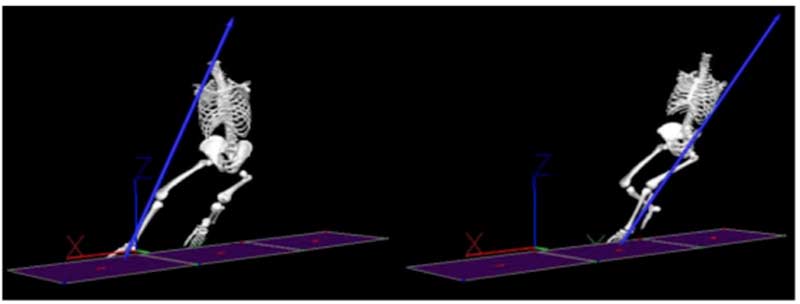

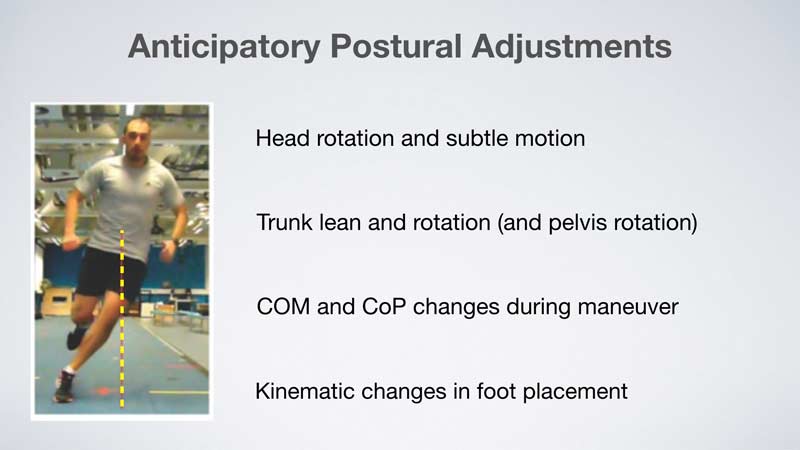

Once we have built the trust of our lower-level coaches, parents, and athletes, we still must implement our program. One philosophy I have come to embrace is that movement matters more than anything else we do in our program. This means that, first and foremost, we want our athletes to move as safely and efficiently as possible in everything we ask them to do. This particular belief really does make as much sense as anything in sports performance. If the athlete has a high level of dysfunction in their technique and movement, it is clearly not the safest situation. Our top priority as a sports performance professional is to do no harm. This means we must not do anything that could lead to a preventable injury.

Nobody would argue that point. If we can all agree on that as a directive for all coaches working with athletes (not just in the weight room, but also in sport), then why are so many coaches ignoring that idea? Why are there too many situations where athletes are not only allowed but instructed to add load to obvious dysfunction? While I fully understand at some point we have to load our athletes, this is a fine line, and a debate for another article. Many, many factors go into how and when each individual coach decides to increase the intensity of the lifts their athletes do. It varies by coach and athlete.

At the very least, I encourage all programs to implement a blocking classification protocol with an evidence-based plan for progression, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XMy point here is that, at the very least, I would encourage all programs to implement a blocking classification protocol with an evidence-based plan for progression. This will ensure that all athletes have the opportunity to gain mastery of basic movements (which will take care of a good portion of dysfunction on its own) prior to adding load/intensity to those movements. Hopefully, coaches will include movement screening or various evaluations within their programming, which will give even more information to the coach and athlete on potential movement issues that they then can work on. Within our program, we focus on these things in an effort to ensure our athletes have a mastery of movement and technique that will lead them to the highest possible level of training they can achieve while leaving as little as possible on the table.

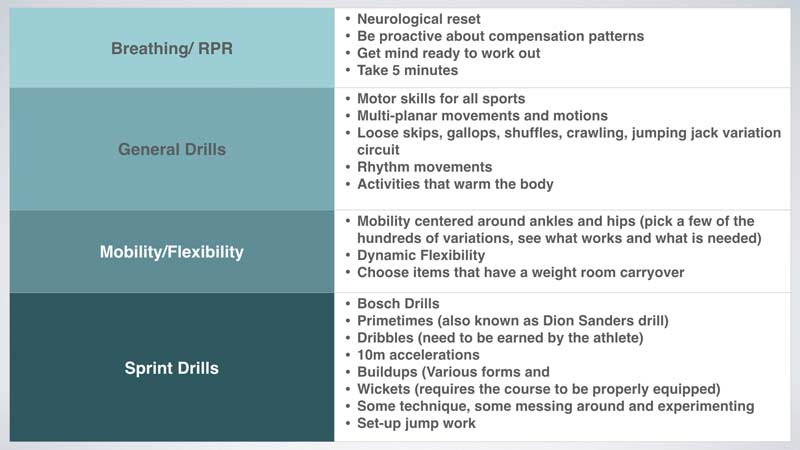

Phase One Transition Program

The first step toward this mastery begins when the student-athlete comes into our program for the first time. At York Comprehensive High School, we have a middle school strength and conditioning class. This is a great advantage for us. I am able to work with those coaches to have our athletes prepared with the basics when they come to me. The vast majority of our Block 0 program is done at the middle school in these classes. In my previous position, I ran a well-attended sports performance camp through our Rec year-round, as well as a summer strength camp in the weight room. Both of these situations were good ones and I encourage everyone to develop similar programs.

The Block 0 program continues in the spring and summer for those athletes. The middle school athletes who attend our after-school program in the spring will regress and progress in preparation for the summer transition. Once we hit summer, I spend the first three weeks reviewing our basic movements and evaluating the status of each individual athlete.

This is the time we begin the transition to everything we will do moving forward. Variations of each movement are broken down, taught in detail, and practiced over and over. We detail how we use the tier system, how the clock and set times work, and every other aspect involved. Our main goal during this time is making sure as many Block 0 athletes as possible are prepared for the transition to Block 1. My next article will go in-depth into the actual details of this phase.

Earning the Right to Train Block 1

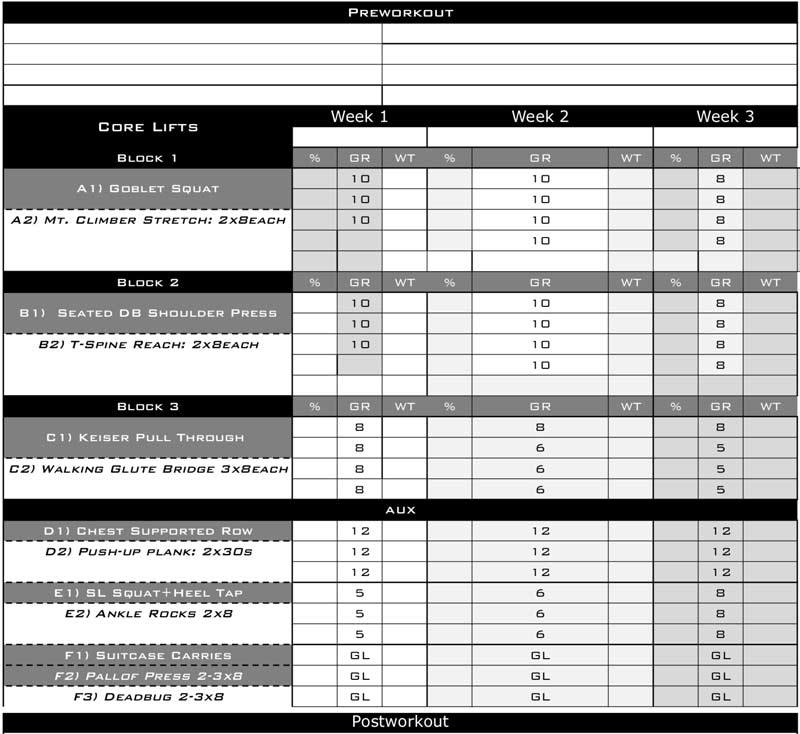

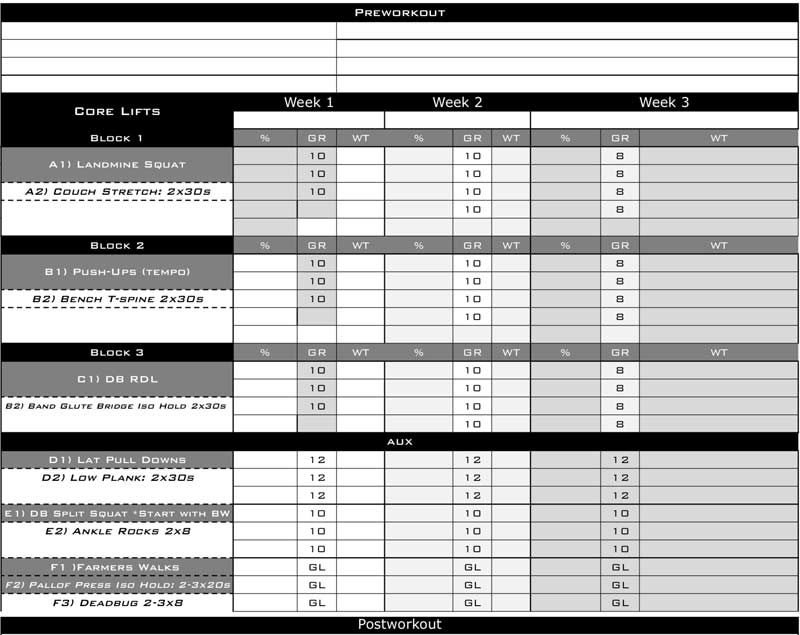

The goal of our transition period in the spring and summer is to have our athletes ready for the climb to our Block 1 “New Lifter” level. This level runs just like all our higher levels do, but with programming differences. We use three “tiers,” although it is a definite “modified” tier system.

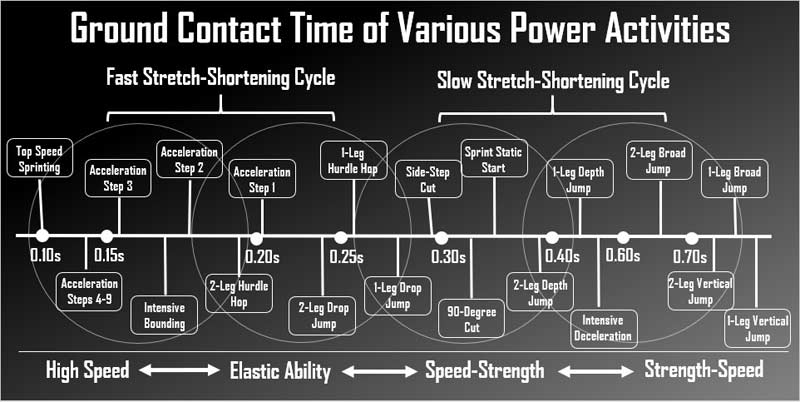

Tier 1 is normally a “dynamic” tier for our higher block athletes. It is where we would do our more power- and speed-based movements. This is one area that we have modified for sure. We still program movements such as a loaded jump in Tier 1 with our Block 1 athletes. The main modification is that we also include strength and even volume-based movements.

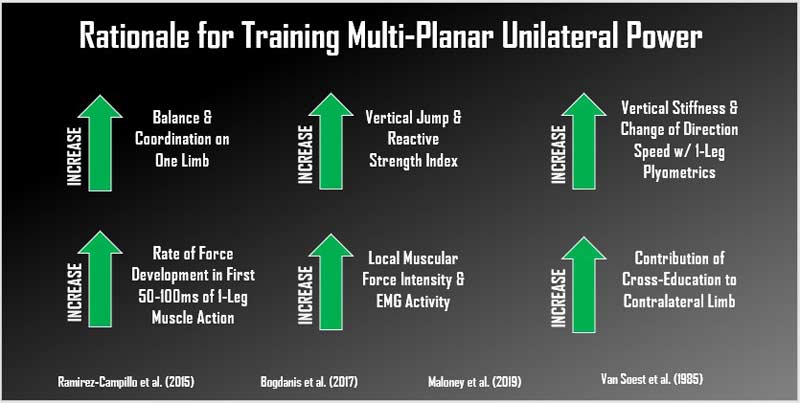

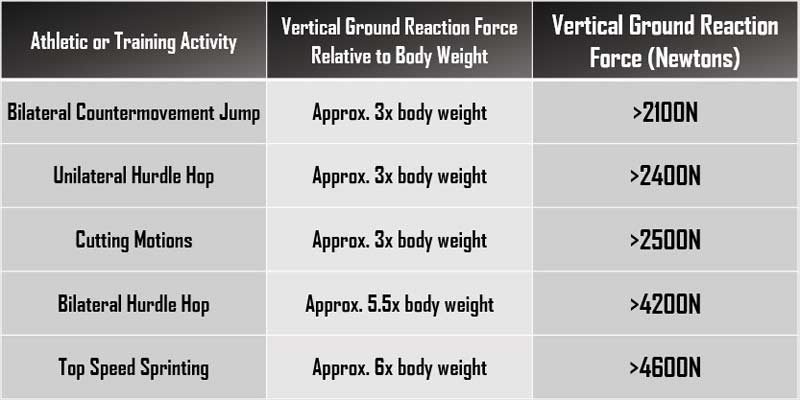

Our thought process is that most of our Block 1 athletes lack strength and size, so we focus on developing that strength to the point where our power-based movements will be more effective. A weak athlete will struggle with force production. So, while we still do some “power” movements (typically pulls and loaded jumps), our main focus is not in that area. We particularly focus on developing strength in the upper back and traps, which the athletes will need for more advanced movements later on.

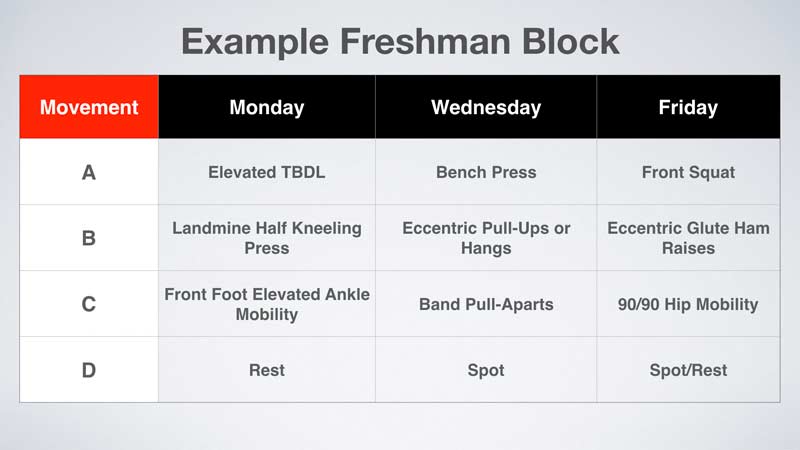

Our Block 1 athletes lack strength and size, so we focus on developing strength in the upper back and traps, which they’ll need for more advanced movements later on, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XTier 2 is always our “strength” tier. This is where our athletes perform our three main types of strength-building movements: trap bar pulls, squats, and bench presses. In our tiers, we always have an A, B, C, and D movement. Typically, in our modified system, D is either spot or rest. In Tier 2, A is always our main movement or variation. B is an auxiliary antagonist movement and C is some sort of mobility or “prehab” movement. A typical week of our Tier 2 session for our Block 1 athletes looks something like this:

Our Tier 3 movements are typically higher-volume, hypertrophy-developing exercises. We use a standard Upper/Lower/Total plan for all three tiers with some slight modifications with our Block 2-4 groups. In a later article, I will outline the exact protocols, sets, volume, and intensity we use and how we came up with the modifications we did.

Goals of Block 1

Our philosophy of “slow cooking” our athletes does not change even as we transition to Block 1. We absolutely program volume and intensity in this block. It is, however, a distant second to our two main objectives, which are mastery of technique and teaching bar speed.

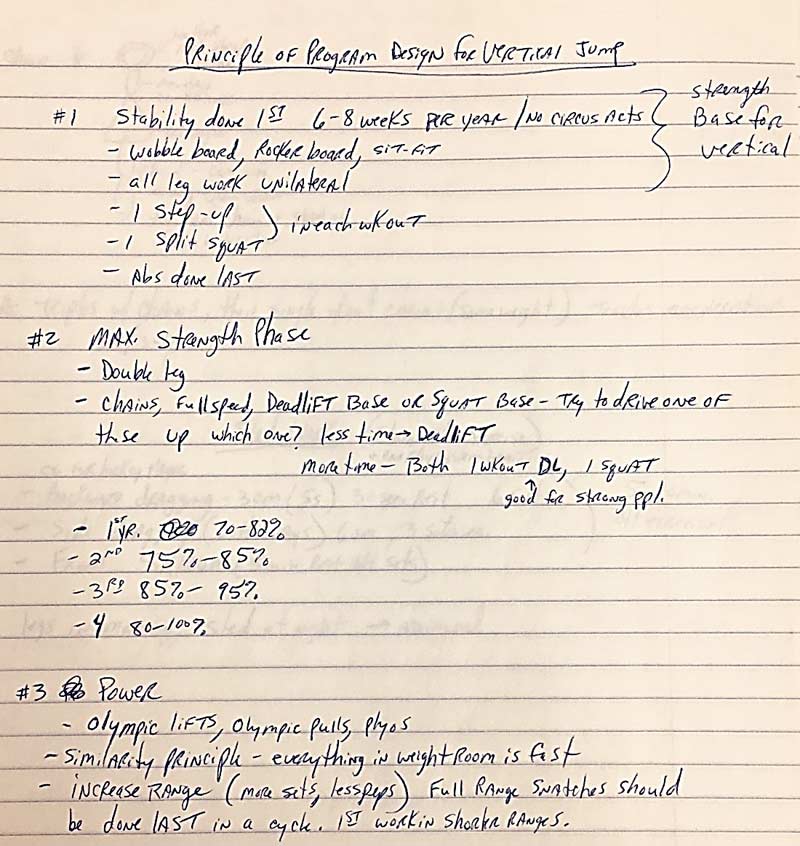

In the book “The System,” Coach Johnny Parker discusses the training he received from Coach Goldstein, a former Eastern Bloc coach and master of the “Soviet System.” If you have not read this book, I urge you to purchase it at once and dive in. One of the pillars of the Soviet system is making sure the majority of the program for athletes is done in an intensity range of 70-85%, moving the bar as fast as possible, but with great technique. Too much time spent below 70% will not be enough to increase strength effectively, while too much time above 85% will result in strength gains, but not the type of explosive strength that translates to sport. We call that the “sweet spot” and we preach to our athletes that bar speed trumps all.

We use Block 1 as the time to begin to develop moving the bar with great speed and technique. We spend about half of our volume in the 50-59% relative intensity (RI) range during this time. The other half is split between 60-69% and 70-79% RI ranges. As the year goes on, we slowly begin to slide the intensity and volume from low to high. By May of the first year, as our Block 1 athletes prepare to transition to “Block 2 Novice,” we may be down to 20% of volume in the 50-59% RI range, the majority in the 70-79% RI range, and 5-10% in the 80-85% RI range.

Our No. 1 coaching cue for bar speed came directly from a phone conversation with Coach Parker, where he talked about not needing an accelerometer back in the day to know they were moving the bar fast. Instead, he listened for the “plate clang” and that told him his guys were moving it. “Make the plates clang” is something I say 100 times a day. I think it is an excellent cue to get our young athletes to understand bar speed.

“Make the plates clang” is something I say 100 times a day. I think it is an excellent cue to get our young athletes to understand bar speed, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XThe final piece of our Block 1 program is a slow and steady increase in volume. Our Block 1 athletes use a modified version of 5-3-1 for the three strength movements that I “stole” from a good friend of mine, Jeremy Evans. I made slight modifications to fit what we do from a volume programming standpoint. In our programming, we use volume as our first consideration for forcing progressive overload.

I have a system for the number of reps of volume per month we program our athletes to do in squats, presses, pulls, Olympic movement (variations), and posterior chain movements (again, to be discussed in a later article in this series). I have a number I want each block to reach in the last month of the school year. I count backward, decreasing 5-10% each month until I reach month one. I then use Prilepin’s Chart to select the proper set/rep numbers and fill in our tiers. We “wave” weeks with high, low, big, and moderate percentages of monthly volume and “wave” days within each of those weeks. High, moderate, and low are based on a set percentage of the weekly total volume count.

Our Block 1 athletes begin with 500 total reps of volume for month one and peak at +/-700 heading into the sport pre-season. We divide those reps up by exercise and begin with 24% squat variations, 20% pulls, 20% pushes, and the rest loaded jumps, Olympic variations (lots of pulls), and PC work. One thing to note is that we only count intensity of 50% or greater. We still shoot for a 2-1 pull-to-push ratio, at least. We just use body weight and band movements to reach that ratio. As the year progresses, if we notice we are lacking as a group in a certain area (bench press, for example), we can slide the percentage to address those issues with more volume. Our Block 1 athletes use partial movements and variations and progress to full movements as they advance blocks.

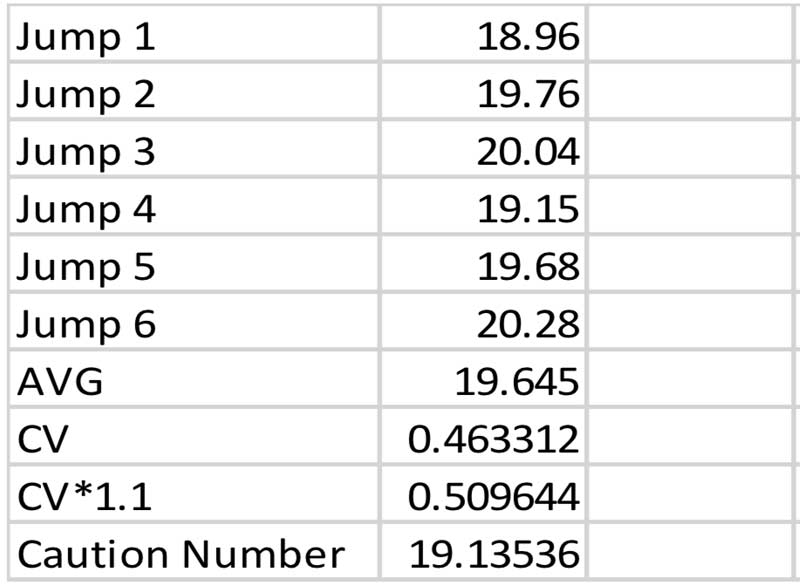

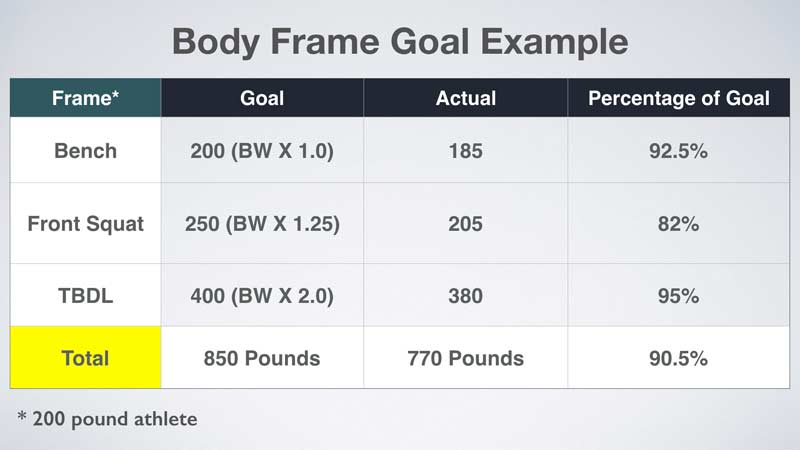

Last, but not least, we test our athletes when we feel they have reached the point of movement mastery and a promotion to Block 2 is a possibility. I will cover our blocking system later. Basically, we use a combo of body frame, body weight, and strength ratios in our three strength movements to recommend promotion. Movement mastery is also a deciding factor.

Our Block 1 athletes must achieve a combined 80% of the following “goals” to be eligible for promotion.

So, for example, if we have a large-framed athlete who has a body weight of 200, his chart would look like this:

This athlete is well above the 80% threshold. If he also masters his movement, we will promote him to Block 2.

Next Steps and Phases

This is a very basic outline of our transition plan for new athletes coming into our program. As I stated, I will add depth to this outline with future articles in which I will go into more specific examples of how we use everything from our tier system to volume and relative intensity. I will break down each step as well and expand on our athlete blocking classification system and how we institute it. I hope this article gives you some insight into the thought process we use when introducing our athletes to our sports performance program.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF