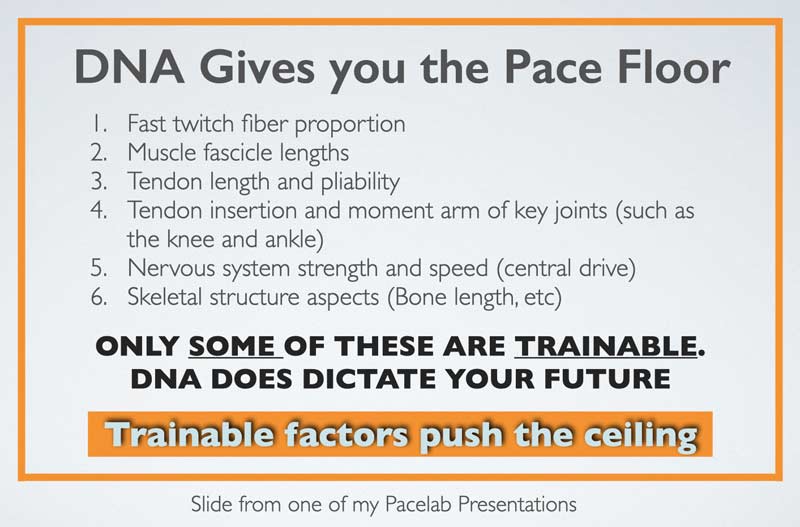

What I’m about to say now may turn many readers away. However, here goes. You may never be as good as you want to be or think you should be. That’s not to put a limiter on drive and ambition; it’s just a sprinkling of reality. Your body and mind may not have the capacity to do so.

However, you can always be better than you are now by adhering to the principles governing the dynamics of performance and respecting the fact we are complex biological systems. We are, in fact, biotensegrity units and not restricted by mechanical Newtonian laws, but more on that later. We are not built solely in the gym!

“Body is a structure made up of muscles, bones, fascia, ligaments and tendons that are made strong by the unison of tensioned and compressed parts, its one interconnected system where the muscles and connective tissue provide continuous pull and the bones present discontinuous compression.” –Eugene Bleecker

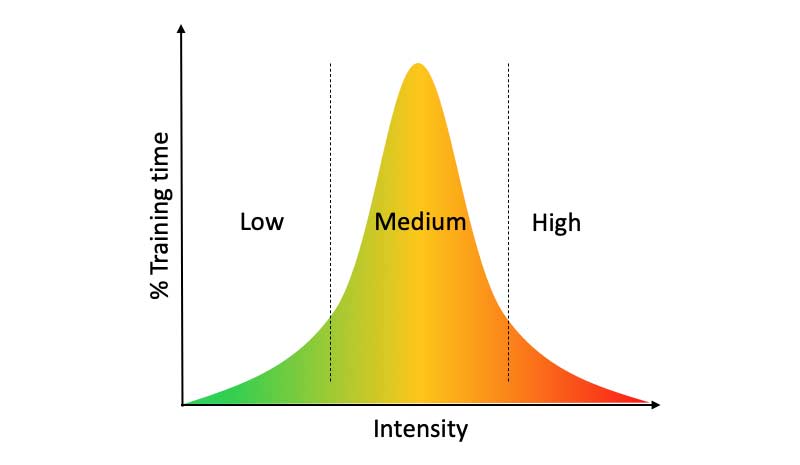

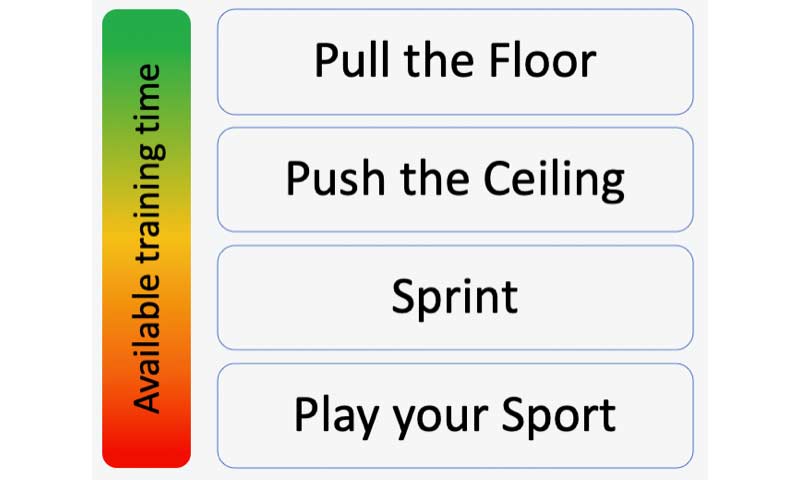

We are born with a genetic floor and everyone arrives on a different level. However, with careful intervention, a throwing athlete can move up the floors until they hit their genetic ceiling. Share on XMy intention isn’t to write a strength and conditioning article but to shed light on why, when, and how all throwing athletes can push up their genetic ceiling. We are born with a genetic floor, and everyone arrives on a different level. However, with careful intervention, a throwing athlete can move up the floors until they hit their genetic ceiling.

Strength phenotypes are 49-56% genetically predetermined. Muscle fiber type is, in fact, 45% genetically predetermined. You are born to be a truly world-class athlete.

Yes, we are back to the nature versus nurture debate: The ability to produce genuine world-class performances is in your DNA (Gene ACNT 3 RR). Fundamentally, an athlete can only increase their genetic ceiling by improving their biomotor, biodynamic, and bioenergetic qualities. No one capacity exists in isolation. For guaranteed progression and transfer of training, they all need to be respected and trained together.

“The number of fibers in a muscle is what’s genetically determined, it is established at the moment of conception by the respective genomes received from both parents.” –Henk Kraaijenhof1

Strength, speed, and power training in a synergistic partnership with technical and tactical work are key to the future of all throwing athletes and the understanding of all factors that govern performance. Individuality also needs to be catered to, taking into account an athlete’s DNA, learning type, personality, neurotype, and anthropometry. Careful appreciation and manipulation of these five traits will determine the success of the program and, ultimately, the future of the athlete.

In this article I will explain the similarities and the differences between my three throwing interests: fast bowling, baseball pitching, and javelin throwing. Similarities exist between the three; however, understanding the differences is what will truly determine performance. It may be radical in its theories, methodology, and application, but my work will always be determined by science-based and research-driven knowledge, along with the less important playing experience (admittedly, only in fast bowling).

I aim to share my findings on testing and profiling fast bowlers in cricket in this article and also give you insight into the way I coach athletes. It will certainly have a bias toward fast bowling, but I will endeavor to provide context in pitching and javelin, too.

So, What Are We Actually Looking for? What Do the Best Do?

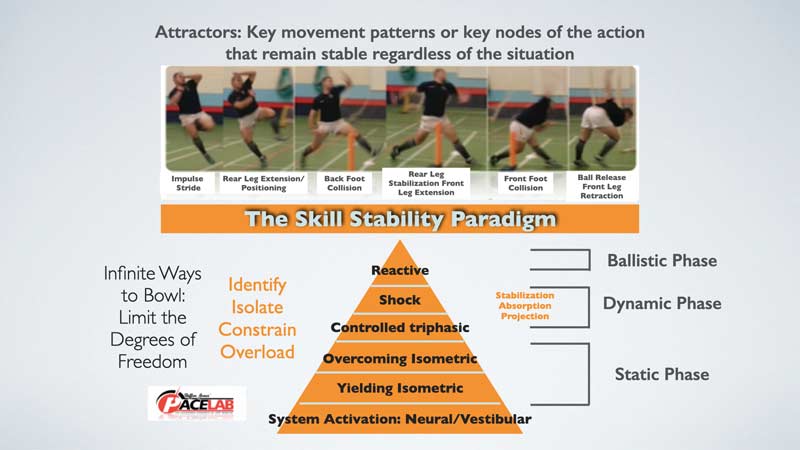

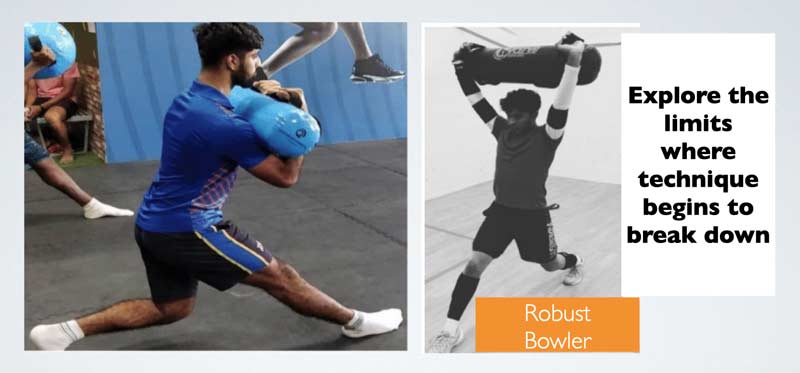

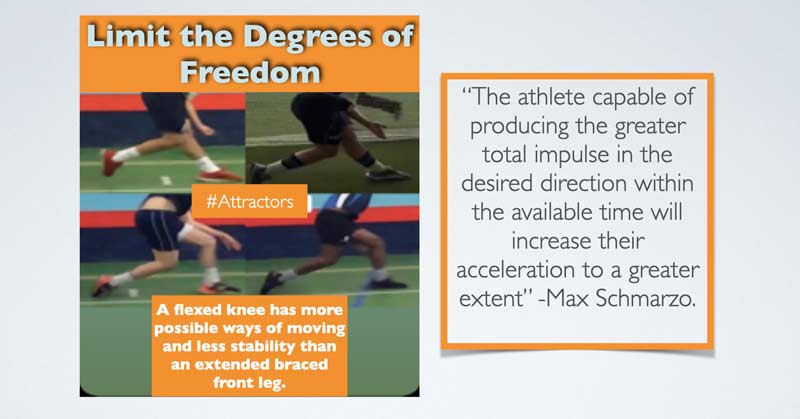

Like most athletic actions, it’s not about building robots who perform the same way in a rigid model; it’s about making sure the “attractors”—the key basic, essential, fixed movements—are stable in the technical completion of the action. The individuality and idiosyncratic elements are the “fluctuators,” changeable components that have degrees of freedom that do not negatively impact bowling performance. When the system’s attractors are stable, it becomes more “robust” (resistant to perturbations) and more “resilient” (resistant to state change/tissue failure).

Fluctuators help us adapt to the environment but are specific to individual bowlers. It’s their own method of organizing and adapting to the environment (self-organizing). Coaches need a careful balance to ensure the fluctuators don’t become too rigid, as is evident in the younger generation of athletes. This serves only to develop a generation of “anti-fragile” athletes for whom any variability causes a dramatic decrease in performance.

I base my approach to coaching throwing athletes, in particular fast bowlers and skill acquisition, on a mathematical model known as the dynamical systems theory (DST).

“DST is grounded in differential calculus and has emerged from the science of behavioral psychology as a useful tool in predicting the behavior of complex systems like ecological environments, economies, and political systems.” –Randy Sullivan, Florida Baseball Ranch

Attractors and fluctuators can also be called the “hard skills” and “soft skills.” The hard skills are the optimum mechanics in an ideal situation and the foundations of fast bowling. They are the general laws of physics and biomechanics as they pertain to fast bowling. These need to be perfect, as they determine the completion of the full sequence. These are the skills that need perfect practice and are hard to ingrain but are essential.

The soft skills are the fluctuations that happen based on task and environmental situations. These are the variable and idiosyncratic skills and unique to every individual athlete. It is essential that both skills are not misunderstood by coaches.

The two layers of attractors are:

Layer 1: Muscles Used – Intra muscle coordination (contractions)

Layer 2: Sequence – Inter muscle sequencing (the technical model)

The key to hitting the “intermuscular technical attractors” is the ability to co-contract and pre-tense around key positions. The ability to pre-tense the muscle around the joint and reduce muscle slack before performing a dynamic action is what separates the top athletes from others.

The ability to pre-tense the muscle around the joint and reduce muscle slack before performing a dynamic action is what separates the top athletes from others, says @SteffanJones105. Share on XIn the three sports, in particular fast bowling and javelin, ground contact times limit the capacity of the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) to impact performance. Intramuscular actions affect each technical attractor and ultimately dictate their effectiveness. The key to any overhead throwing efficiency is to make your attractors stable (but not too stable) and to have some fluctuations available for adjustability, but not too many.

Fix the technical positions by contracting (co-contracting) the muscles around the node, which then acts like a straitjacket for the technique. This is why the Pacelab Skill Stability model is built around isometric training.

There are similarities between all three events—fast bowling, javelin throwing, and baseball pitching—due to the common value placed on:

-

- Orientation: Horizontal force vector; body mass and implement

-

- Separation: Switching of limbs and separation of trunk and lower body to create torque

These two govern everything.

“The key to technical coaching is identifying the balance between enough separation and orientation.” –Jonas Dodoo, Speedworks

We need to understand and respect three general concepts that underpin any coach’s knowledge for all speed and power sports: athletic posture, sequencing, and rotation.

Everything about rotational sport is about generating, storing, and utilizing kinetic energy up the kinetic sequence in a strong, stable, technical model. This is from the floor all the way into the implement, from proximal to distal, and the largest segments generating torque into the smaller segments. It is called “sequential acceleration.”

Issues arise when blockages/leakages occur up and down the chain, which in my view is born out of an over-reliance on heavy strength training. Current strength and conditioning programs place more emphasis on muscles or movement in one plane than respecting the natural force multiplier we have in our body—the fascial system.

There is a natural fascia system in the body that’s key to any rotational sports. Knee-dominant bowlers, in particular, will need careful understanding of this system and how to train it.

The body searches for efficiency: the stiffness and tension we create in some areas will lend themselves to doing more efficient work with less effort. The kinetic chain in overarm throwing/bowling is initiated by the heavy proximal segments (the trunk), followed by the lighter distal segments (the arm segments), resulting in the distal segments rotating faster than the proximal segments.2

“…the athletic development world, unfortunately, has likened movement to a series of pretty lines and angles in the sagittal ‘front to back’ plane of movement. The principle of torque, a common trait of the world’s fastest athletes, flips the linear, ‘pretty-angle’ mentality on its head. Joints work using adduction and abduction in the frontal plane, along with twisting in the transverse plane to get a more powerful loading (and unloading) of the fascial systems of the body, and muscles react to that positioning.” –Joel Smith3

The fascial system dictates that we move in a tri-planar pattern. Respect torque. We are torque beings:

“Humans are torque beings; and torque is rotation or twisting. We are more efficient moving with rotation than we are linearly. Muscle fibers run at angles, not linearly. We have joints that allow us to move the endpoints of the muscles farther away from each other via rotation. Linear movements keep the distance between endpoints fixed which makes it difficult to elongate a muscle.” –Adarian Barr

Kinematic Intermuscular Attractors: The Technical Model

I think it’s important that I reiterate at this point the difference between style and technique. Everyone has their own style based on how they organize themselves in relation to environment, task, and organismic constraints. Truly elite performers, however, have the same technique but individualize their movement and coordination based on the following seven broad categories. These are based on the work of Joel Smith of Just Fly Sports, with the addition of my observations from my 13 years of coaching and 20 years as a professional player.

-

- Neurochemical type

-

- Pacelab hip or knee dominance

-

- Training tolerance

-

- Muscle-driven versus fascia-driven athletes

-

- Ratio of force transfer

-

- Explosion- or implosion-based neuromuscular patterning

-

- Training and chronological age

These seven differences will also impact hitting the kinetic attractors. While it’s beyond the scope of this article to cover each aspect, the key message is simple: Everyone has a different journey toward the end results but will always have the same intention and end position.

“If we are to teach correct movements, understanding the biomechanical principles underpinning what ‘correct’ looks like is critical. Think about technique versus style—correct technical practice in sport is governed by inarguable biomechanical principles whereas stylistic differences are often an adaptation of techniques, based upon individual variation, nuance, or faults. People often confuse the two.” –ALTIS: Foundation Course

I’ll begin with my specialization and passion: fast bowling.

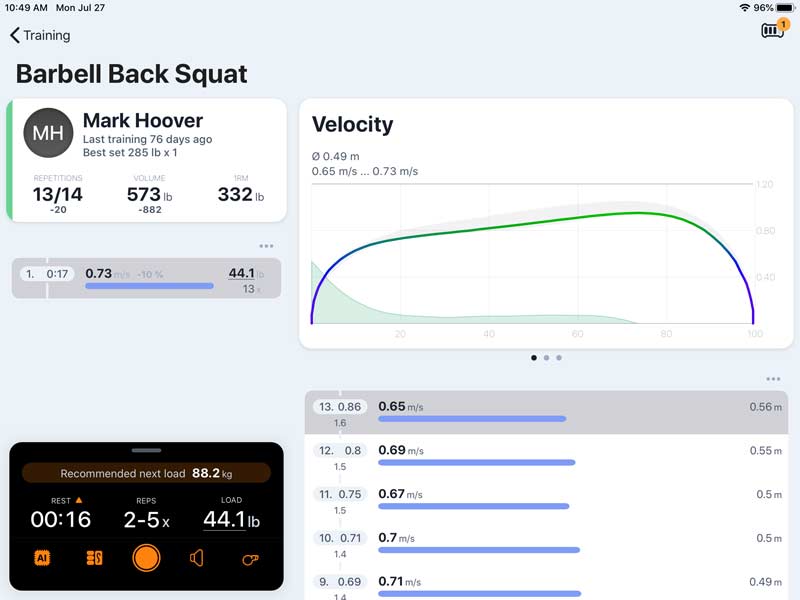

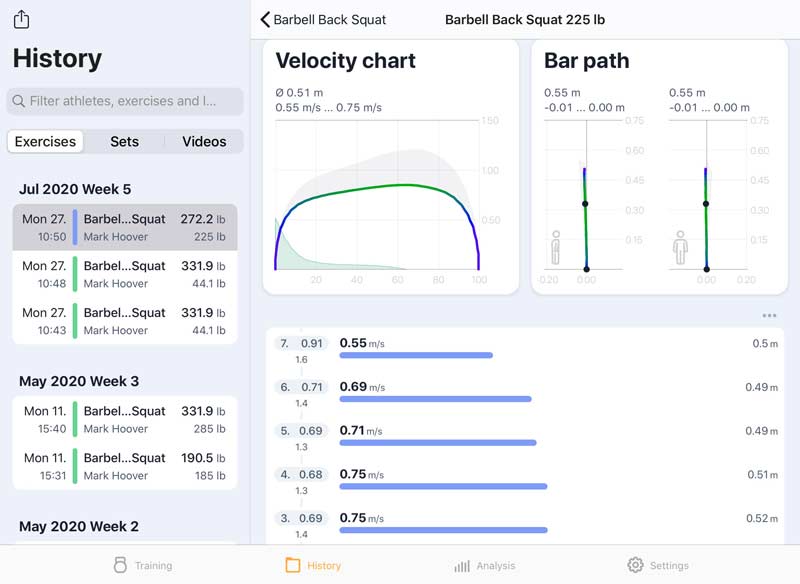

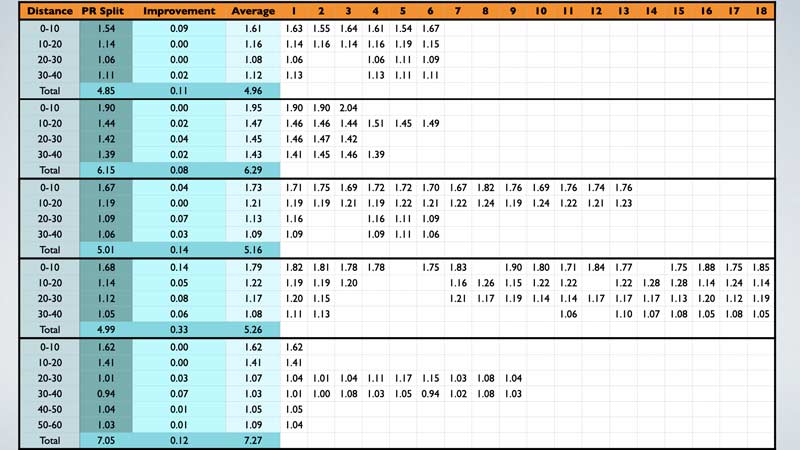

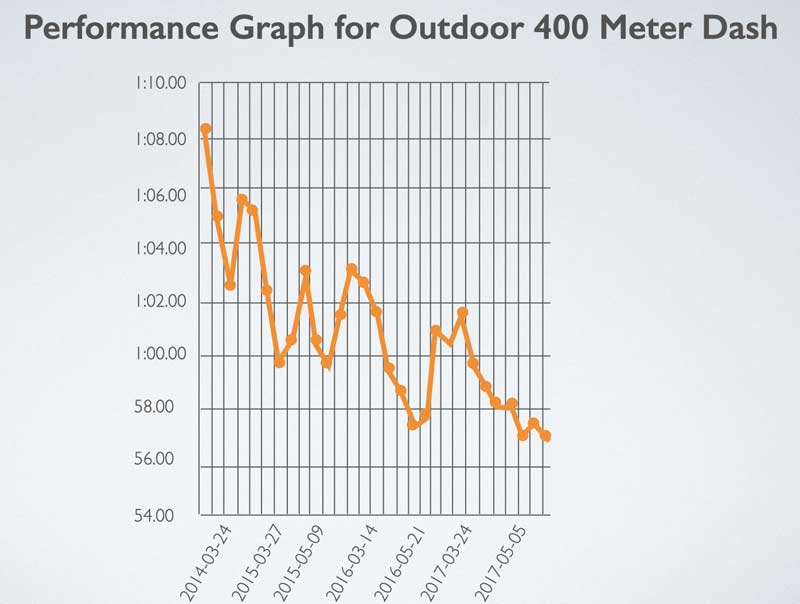

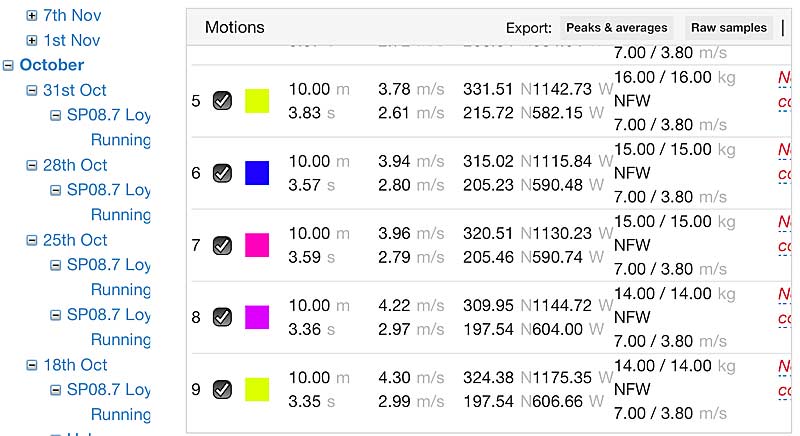

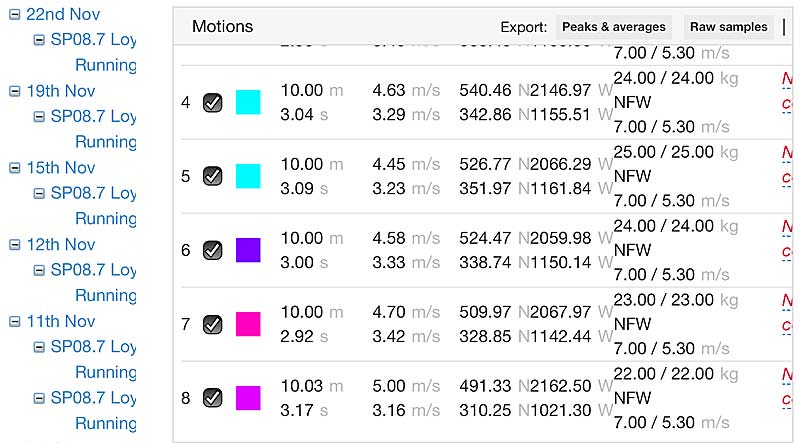

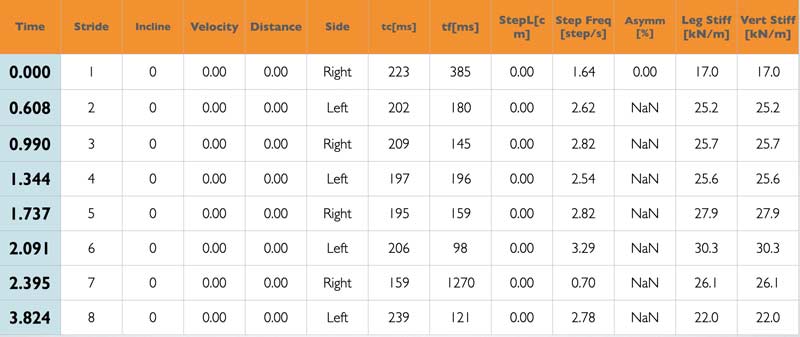

The following are based on the Pacelab profiling system, which utilizes the 1080 Sprint, Muscle Lab contact grid, Stalker Pro speed gun, and ForceDecks for isometric testing. These four testing tools make up the “Pacelab Velocity Matrix”—they provide the key performance indicators (KPIs). These are my findings based on hundreds of bowlers, from 60–95 mph bowlers, both boys and girls, assessed over the last three years.

There are four key aspects that determine elite performance in fast bowling. These are the kinematic attractors:

-

- Approach velocity

-

- Collision control in the impact zone

-

- Maintaining momentum throughout the impact zone into the delivery zone

-

- Sequential acceleration from proximal to distal

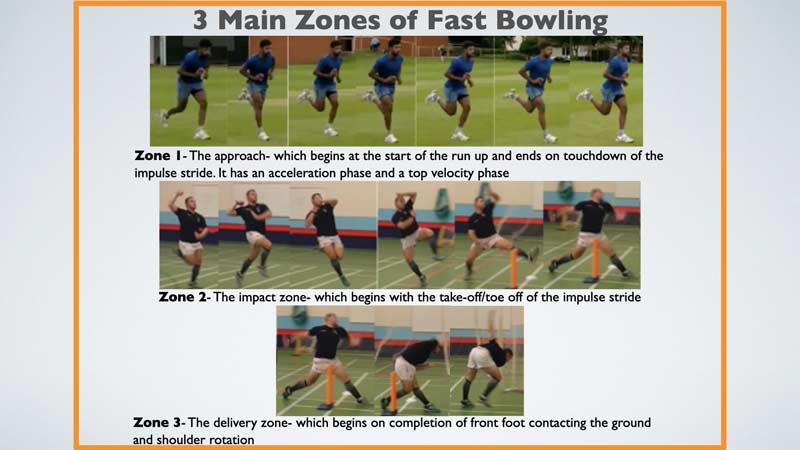

I split fast bowling into three main zones, as seen in figure 6.

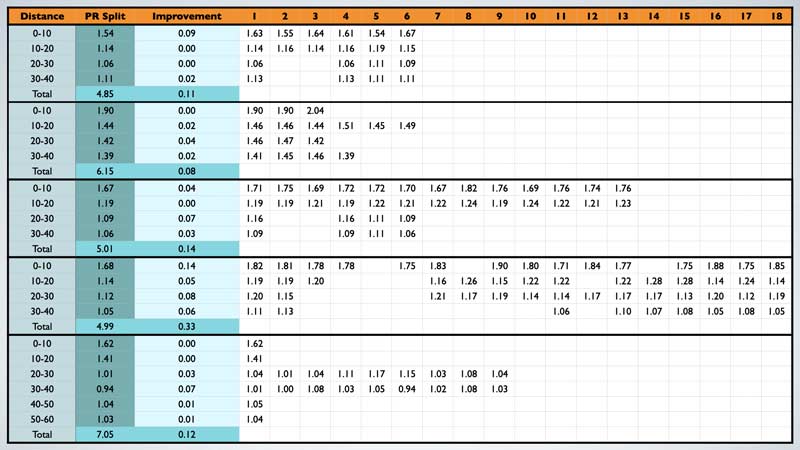

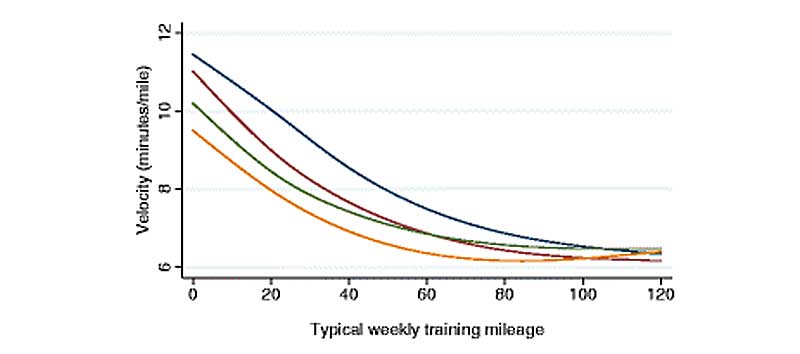

1. Approach speed and maintaining momentum through the sequence: The faster bowlers run in at higher velocities measured in meters/second and decelerate less onto front foot contact.

The fastest bowlers in the world run in quicker. That’s it, simple. There are clear outliers, but based on 1080 Sprint data, when bowlers are guided into running in more quickly, ball velocity increases. Issues arise when the athlete doesn’t have the force management capabilities to maintain stability and control in the delivery.

The fastest bowlers in the world run in quicker… Based on 1080 Sprint data, when bowlers are guided into running in more quickly, ball velocity increases, says @SteffanJones105. Share on XDifferences exist between hip- and knee-dominant bowlers. Knee-dominant bowlers need more time for rotation on back foot contact (BFC), so they need more control at the impact zone. However, the key factor is the need for momentum, which is why strength training is more essential for a knee-dominant bowler.

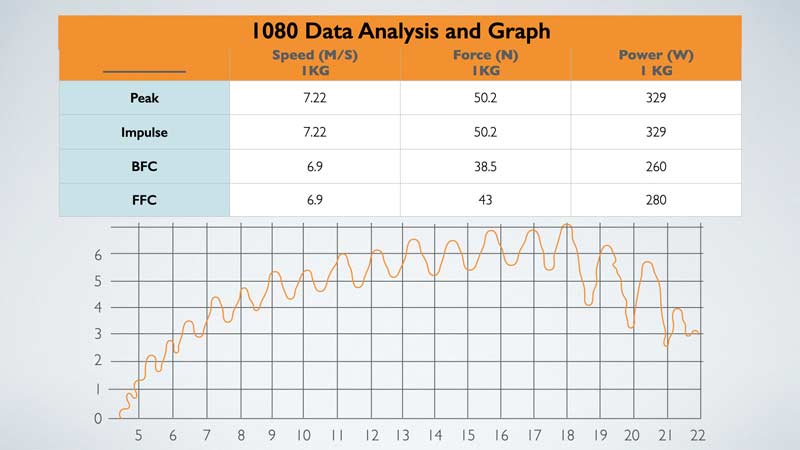

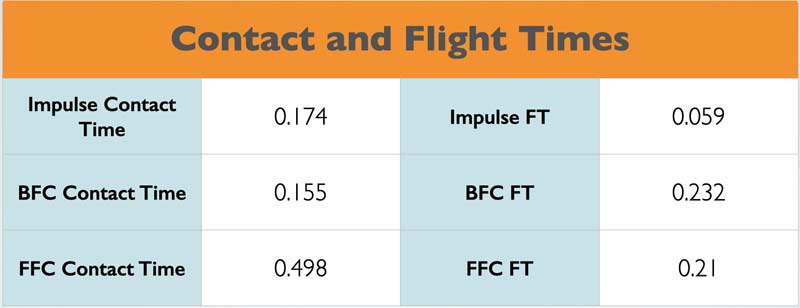

Below is the profile of a knee-dominant fast bowler who relies on time on BFC but is still able to maintain momentum due to high biomotor qualities. The key is the peak velocity is hit into the impulse stride at more than 7 m/s and then he is able to maintain a large percentage into front foot contact (FFC) with a strong, braced front leg.

However, this was not always the case. On initial profiling, the data showed energy leakage and a lack of momentum into the impulse stride and inefficient force management on the BFC. Spending too long on rear-side mechanics will negatively impact front-side mechanics, which ultimately is a key determinant of ball velocity. Front side is a consequence of rear-side mechanics, and the back foot is merely a pivot/fulcrum for the bowling action. Poor ability at this node impacts greatly on the front foot contact and stabilization of the lever of the front leg.

The intervention method to change these numbers involved 1080 Sprint resisted heavy walks with an added Lila Movement Exogen Suit, skill stability isometric training, flywheel training, and extensive jumping (pogo jumps/hoping). These were all performed in a two-week period. Ball velocity increased by 3 mph.

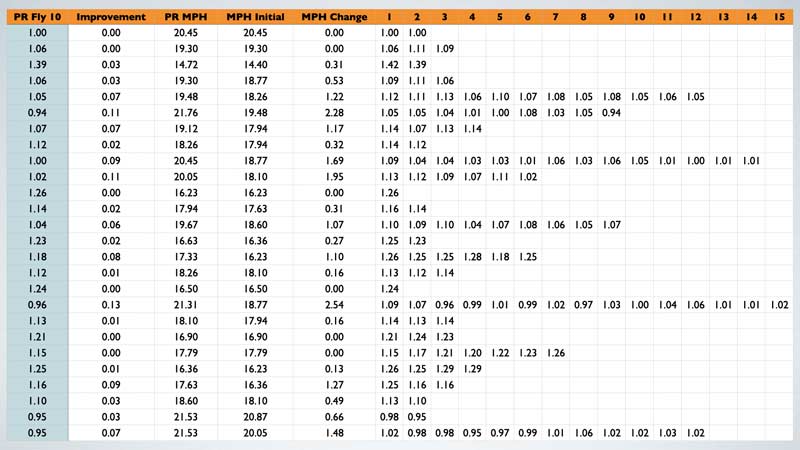

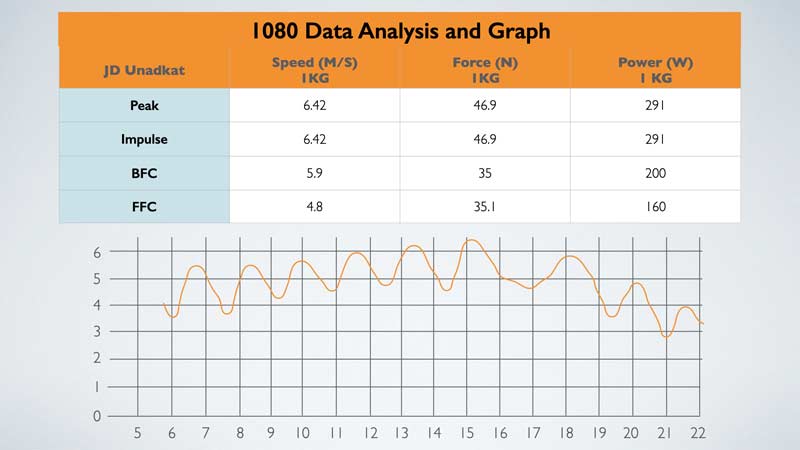

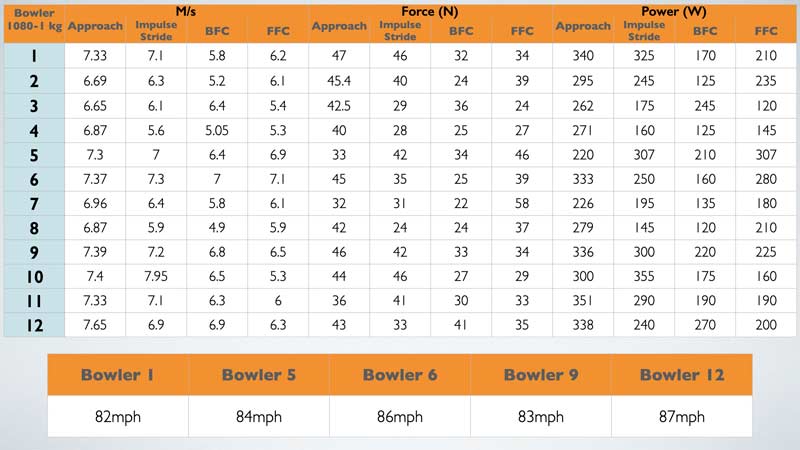

The above data is for a bowler who bowls early 80 mph. These are the numbers for 12 bowlers in terms of approach velocity and the maintenance of force and power into the FFC. It’s essential to note these are the ball velocities on the Stalker Pro speed gun, and they are 3-5 mph slower than TV measurements (who said speed doesn’t sell?).

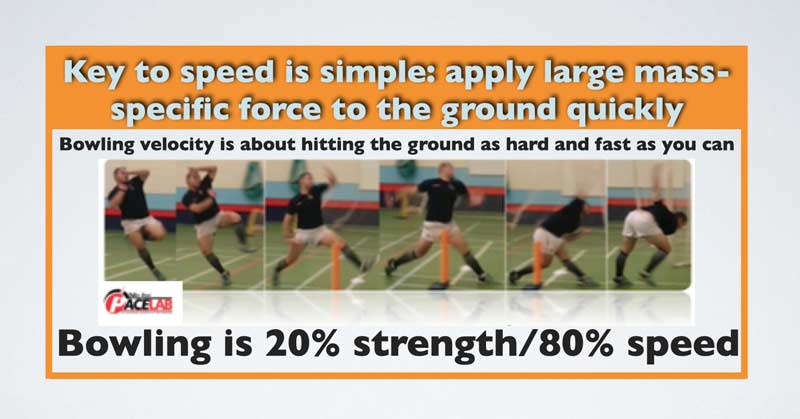

I place a premium on sprint training. The key message for me is simple: Attack the impact zone, control the collision, maintain momentum from the impulse stride into BFC, and transfer the momentum into FFC, which causes a kinetic collision up the sequence into the implement. Note on the above figure that the fastest bowlers have the higher approach number; however, there are outliers.

Three years of in-house research has demonstrated that improving the velocity bowlers run in at will have a positive correlation with ball velocity. Fast bowlers and javelin throwers need to be better sprinters. Hitting FFC faster with more force will help you bowl faster and throw further. However, this increases the dynamic complexity of the sequence and places a higher premium on eccentric strength.

Hitting front foot contact faster with more force will help you bowl faster and throw further, says @SteffanJones105. Share on XControl of the collision requires the ability to avoid deformation on ground contact. Flexing/compliance on contact increases ground contact time, which is not favorable to bowling or sprinting quickly. However, don’t rush to stand under the barbell to squat until you drop. That won’t help you if your ground contact time is less than 0.20 seconds, and if it isn’t, then you definitely won’t be bowling quickly!

You have limited time to make a difference. Long ground contacts and system compliance lead to a dissipation of energy. A collision is how the body absorbs and redirects energy. The knee being bent extends the collision time. This can happen in two different ways:

-

- The knee bends prior to impact.

-

- The knee bends after the collision or the foot coming in contact with the ground.

Understanding the impact forces have on the body is key. Do they flex on contact due to anthropometry or do they fail to control the collision due to poor eccentric capabilities? Hip-dominant bowlers, who, due in part to fascia stress lines built over time and myelinated patterns, stay “rigid” on back foot contact may not necessarily have the biomotor qualities to utilize this capability.

A good fast bowlers’ knee, whether hip- or knee-dominant, is bent prior to ground contact and maintains that angle throughout the ground contact phase—whatever that angle is. They don’t lose energy; they use energy. A weaker bowler’s knee will bend after ground contact occurs, whether hip- or knee-dominant. The main difference between hip-dominant bowlers and knee-dominant bowlers is system stiffness that leads to eliminating muscle slack quicker.

Stiffness can be identified as the extent to which an object resists deformation in response to applied force. It can be measured by applied force divided by change of length in newtons/meters (n/m).

The opposite of stiffness is compliance, and it requires less force to cause deformation. The forces involved in fast bowling are unmatched in most sports skills: 4-5 times body weight on BFC and 8-10 times on FFC. This is why compliance is not conducive to fast bowling. Compliance leads to increased time for segments/nodes to move, which we haven’t got during bowling; a lowering of COM on contact, and therefore a reduction in gravitational momentum into FFC; an increase in “contact patch” during the approach, increasing GCT during running; and more flexion on BFC, leading to increased GCT.

According to Max Schmarzo and Paul J. Fabritz, there are four types of stiffness that impact any locomotive skill like fast bowling:

-

- Body system – leg stiffness

-

- Individual joint – ankle stiffness

-

- Active stiffness – muscle and CNS

-

- Passive stiffness – tendon and fascia

When we hit the ground, our aim as fast bowlers is to impart as much ground reaction force (GRF) as possible relative to our mass (MSF) in as little time as possible (GCT). When sequenced correctly, we create unified TENSION throughout the system via the fascial system and COMPRESSION via the contractile elements of the muscle. That allows us to eliminate muscle slack and use the body as a unit to complete the delivery.

When running, the energy comes from an isometric contraction of the agonist muscles, allowing connective tissue tension, both at the tendons and the fascia, and muscular relaxation in the agonist muscles. Having the ability to co-contract and pre-tense prior to impact and relax post impact is the difference between the true elite and the also-rans. The law of reciprocal inhibition is something the best adhere to!

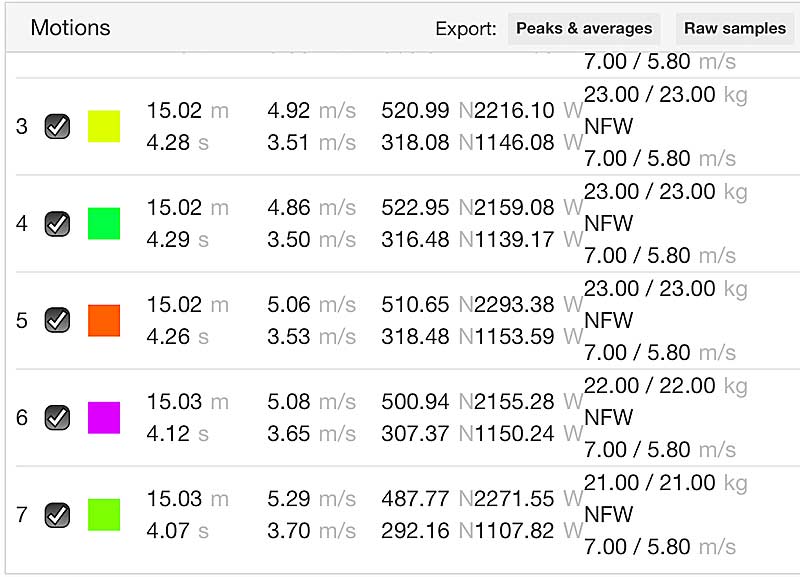

The data on 1080 is for fast bowling, but based on it, there is a positive correlation between the approach in javelin and release speed, which directly impacts spear distance.

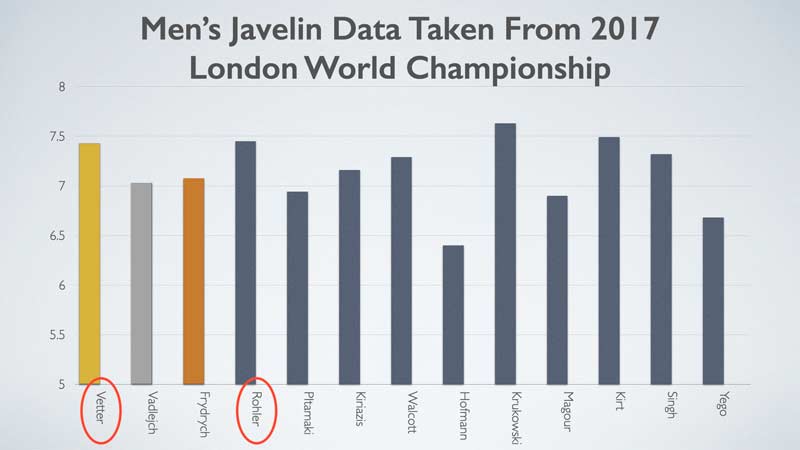

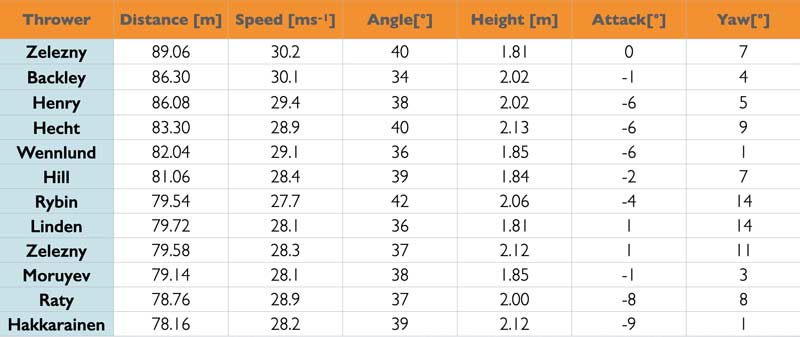

Above is the data for various javelin throwers in the last five years. Once again, it is evident that the faster the approach, the farther the throw. The interesting data here is the fact two different throwers, Rohler and Vetter—one being knee-dominant and the other hip-dominant—both place an emphasis on creating momentum into the delivery. How they then organize themselves into completing the throw is unique to them. However, the constant is approach velocity. One relies on the stretch shortening cycle and torque while the other relies on back foot stiffness and maintaining the momentum of the center of mass into front foot block. The key is energy transfer.

With regard to approach velocity in both javelin and fast bowling, when the numbers were higher on the run-up speed in m/s and power highest in watts, the ball velocity was always higher. Share on XIn summary, with regard to approach velocity in both javelin and fast bowling using the 1080 Sprint for fast bowling, when the numbers were higher on the run-up speed in m/s and power highest in watts, the ball velocity was always higher.

2. Switch legs/reposition the back-foot contact leg faster and land with a stiff back foot contact whether hip- or knee-dominant. Knee-dominant throwers will spend longer due to accessing the SSC to create hip internal rotation and subsequent torque, but still need to remain stiff and avoid deformation.

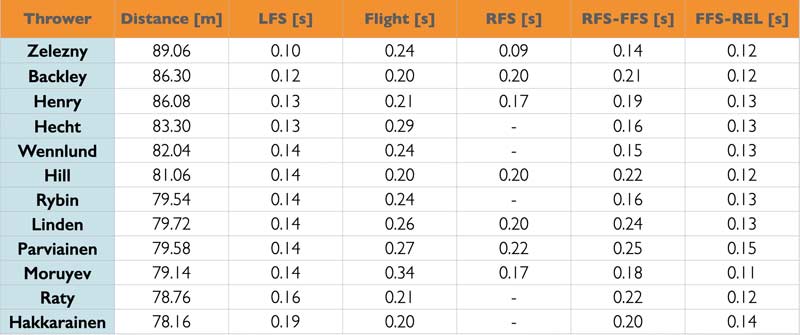

The aim of a fast bowler and a javelin thrower should be to generate as much momentum into the impulse stride, then maintain that into BFC and onto FFC. Javelin throwers turn earlier into position during a crossover phase so they will lose more momentum, but like fast bowlers, ankle stiffness and short GCT are integral to their success.

The shorter the ground contact time on impulse stride (LFS) and back foot contact (RFS), the farther the distance.

This is the same with fast bowlers. The fastest bowlers in comparison to their peers have a shorter ground contact time(GCT).

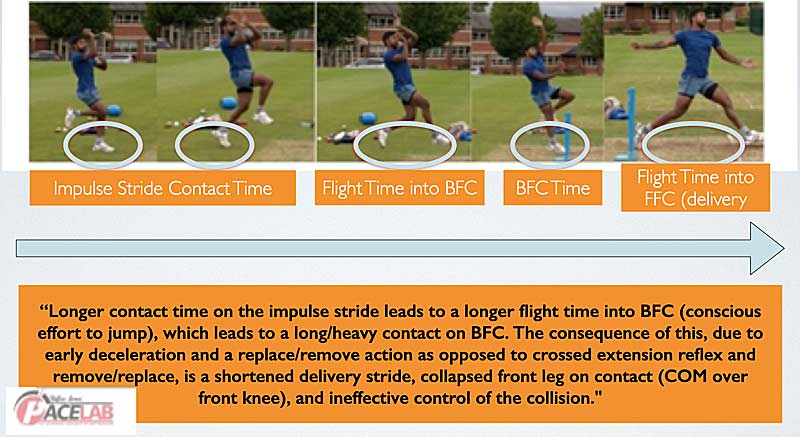

Contact times impact flight times. This is why it’s integral to train ankle stiffness, as it determines the quality of the flight time. Sprinting and fast bowling are reflexive actions. Energy is maintained through every stride via the crossed extensor reflex, which is dictated by the quality of the previous ground contact. The more force imparted into the ground, the better the projection. The stiffer the contact, the more the reflexive system aids in performance.

In my opinion, there should not be a definite deceleration at the impact zone. It’s a continuation of the sprint itself. This is different than other opinions, but based on data, the bowlers who keep running through the crease (area where they bowl) and don’t consciously try and “jump and twist” into their delivery bowl faster.

The fastest hip-dominant bowlers have the shorter GCT on back foot contact, while knee-dominant bowlers need longer to store energy.

The differences in time required to achieve each of the muscle action phases play a role in time spent on BFC. The knee-dominant/muscle-driven bowler requires extensive time spent on BFC when compared to the spring/fascia-driven bowler. More time spent on BFC will lead to poor kinematic and kinetic sequencing that inhibits the ability to complete hip-shoulder separation, which is one of the key kinematic attractors of fast bowling. However, increasing the time in the upper extremities will allow correct synchronization of the upper and lower half. This is called the “long-arm pull,” and it characterizes the “slingers.”

Credit: Max Schmarzo and Matt Van Dyke.

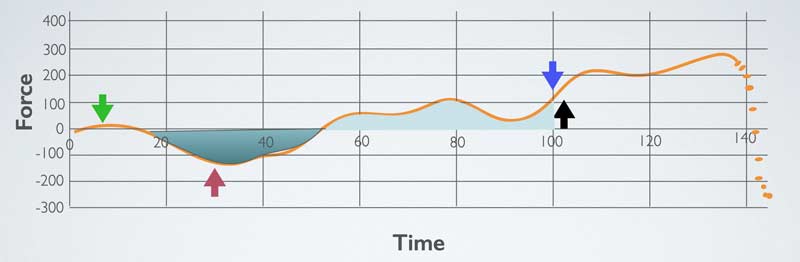

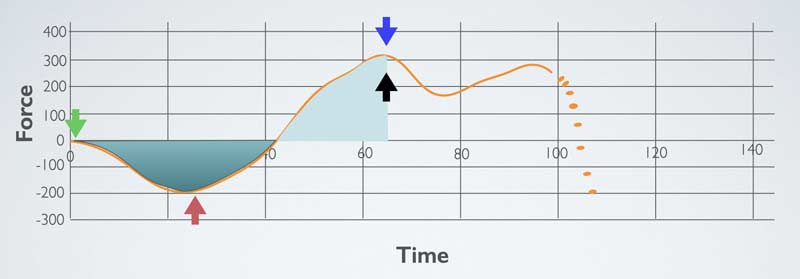

On BFC, the bowler begins traveling downward (green arrow–gravitational momentum), then begins to “ramp up” the force placed into the ground to begin decelerating their downward force (red arrow–eccentric contraction). They eventually (hopefully) produce enough force to come to a complete, although brief, halt at their bottom position (blue arrow–isometric contraction), before immediately beginning their propulsion upward (black arrow–concentric contraction) through to front foot contact (spring mass model).

Credit: Max Schmarzo and Matt Van Dyke.

The differences between the lower-level/knee-dominant, and higher-level/hip-dominant fast bowler quickly becomes clear in these two examples. The knee-dominant bowler who lacks stiffness in their tendon is not able to create as much “negative” force as rapidly, as their body understands they will not be capable of overcoming this produced force in an efficient manner. On the other hand, the hip-dominant bowler, relative to the lower-level bowler, is much more capable of rapidly “pulling down” into the optimal back leg/knee-flexed position due to their tendon stiffness and isometric strength. This can be achieved as the athlete is able to “ramp up” their force rapidly, even when this large negative force is applied.

The fastest sprinters and the more athletic fast bowlers and throwers in the world switch their limbs in the air while running (remove-replace action), maintain a stable trunk with a high center of mass (COM), and claw back and under as foot contacts the ground on the outside edge of the foot. This comes from stiffness at the ankles, power at the hips, and stability at the trunk. Due to these three factors, they maintain momentum with every stride.

We know 70% of top velocity sprinting occurs after seven strides, and the remainder is about maintaining momentum and avoiding decelerating on ground contact due to poor technique. This is the same from impulse stride to BFC. As mentioned on numerous occasions, fast bowlers should aim to become better sprinters while becoming strong enough to manage the collision. Spend more time getting your sprinting technique effective and efficient.

Changing the body’s direction of movement at high speeds requires a tremendous amount of eccentric strength to minimize the time of the amortization phase and increase the ability to transfer the horizontal kinetic energy developed in the approach to slight vertical lift in the impulse stride and large gravitational momentum into the front foot contact. However, as previously stated, this is not entirely built in the gym, as specific strength based on the intra and inter-coordination of muscles is the key to technique in a high-octane skill like javelin throwing, fast bowling, and pitching.

Fast bowling relies on the reflexive system more than the muscular system. However, the quality of the reflex is determined by stability and control on impact, which can be enhanced via improved biomotor capacities from training such as shock method and isometric training. I place a lower value and need on concentric-focused training.

Propulsion is a consequential action, not a determining action. The quality of moving forward relies on the quality of initial contact. The delivery stride is determined by the quality of the back-foot contact. Research shows that the delivery stride should be approximately 70% of the athlete’s height. This provides a strong base, allowing the kinetic sequencing to occur more efficiently.

Based on Verkhoshansky’s work, it’s evident that the CNS stimulation received via the contact portion leads to a higher rate of stretch—myotatic reflex. This rate of stretch can be increased via:

-

- Height of jump into contact – How high you jump into the gather from the impulse stride, which is the flight phase between the penultimate step ground contact and back foot contact. This has consequences.

-

- Mass of body into contact – How much body weight you carry. This has consequences.

-

- Velocity of body into contact – How fast you hit BFC. This also has consequences.

The magnitude and the rate of stretch will determine the quality of the propulsion phase. Due to the short GCT on the BFC, I discourage bowlers from jumping high to create the CNS stimulation. My advice is that they manage velocity by hitting the contact at max velocity in the approach.

In summary, stiff back foot contact is essential to bowl quickly and, in fact, throw far. It allows a stable pivot point but also impacts the front side/swing leg/front leg mechanics.

3. Brace their front leg on contact and take less time to bring their front foot down from above after back foot contacts.

As a general rule, but respecting athletes with different styles, the fastest bowlers and javelin throwers who throw further brace their front leg. On ground collision they maintain the straight leg, which enables one fulcrum at the hip and a pivot point where first hip rotation, then torso rotation and shoulder rotation, and finally wrist rotation can produce torque and create sequential acceleration.

Due to the ground contact times and the high angular and linear momentum produced, muscles do not have time to have a dominant effect on the completion of the skill. Athletes need to be ready to withstand the impact before it happens. In effect, they need the ability to pre-tense (brace) their muscles before impact. This will be aided by an effective crossed extensor reflexive action from a stiff back foot contact. This co-contraction is integral to the success of bracing on front foot contact. It can be highlighted by full extension of the swing leg/leading leg before impact.

The most important direction for a fast bowler isn’t the vertical but rather the anterior/posterior direction, says @SteffanJones105. Share on XThe most important direction for a fast bowler isn’t the vertical but rather the anterior/posterior direction. The foot comes down from above and doesn’t slide in. A foot plant from above allows the athlete to maintain momentum and limits the decelerative impact on the initial ground contact. Every stride pulls the athlete forward. This is the ideal motion in the approach and on FFC. This is also relevant to pitchers, as the following study highlighted.

According to a recent study, “force imparted by the stride leg against the direction of the throw appears to contribute strongly to achieve maximum throwing velocity.”4

The fact that the stride leg applies force against the direction of the delivery means that this force is being applied in a posterior direction. High velocity is maintained toward the target by applying force in the opposite direction.

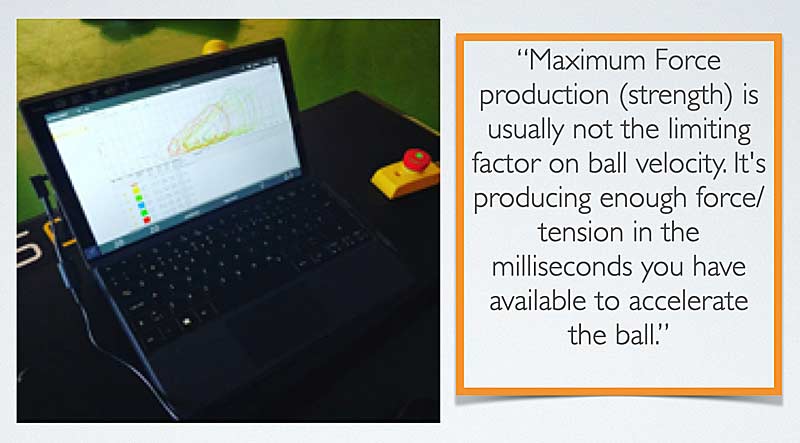

In order for our fast bowlers to produce high velocities, they must first provide the technique to create a large impulse. The greater the impulse, the greater the velocity created. Not to be confused with the “impulse stride,” impulse is the amount of accumulated force throughout a movement (force x change in time). The faster bowlers spend longer on FFC and create a larger impulse. Due to the limited time to produce force on FFC, it’s not just about how much force a bowler can generate over a given period of time, but also the instantaneous force the bowler can produce.

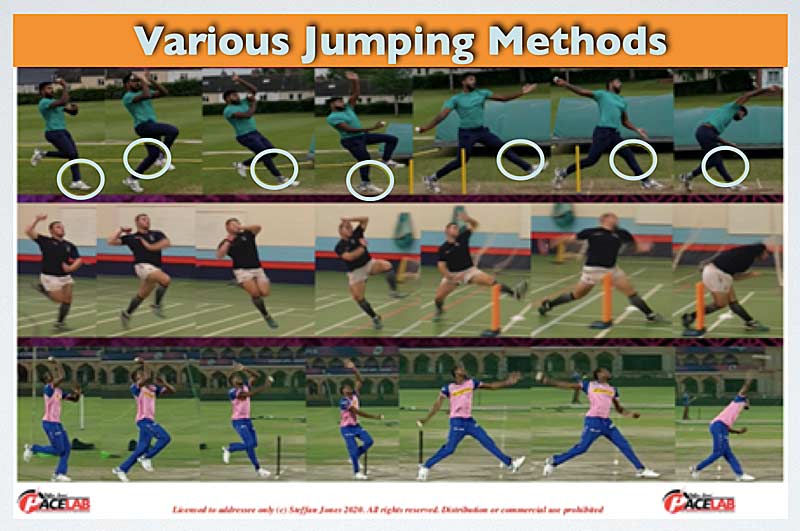

Impulse has tremendous applications in fast bowling, as the aim is to maximize force production in specific moments (i.e., force produced at the joint angle during each key node in fast bowling). The goal outcome for a fast bowler is to increase the velocity of the ball. To do this, we must either increase the time over which the force is applied or the amount of force produced in a given time. Developing a larger impulse or generating greater force over a set period of time improves RFD, which can increase the likelihood of success. This is why I place a premium on various jumping methods in specific positions and skill stability isometric training, isometrically holding positions and contrasting with a ballistic exercise from those positions.

4. Correct timing, sequencing, and separation of trunk rotation and arm rotation:

It’s the timing of the separation in relation to peak ground reaction forces, not the separation speeds themselves, that differentiate the genuine fast bowlers from others. Faster bowlers experience the separation later, but the greatest stress is experienced closer to or even after front foot contact. As with most skills that are performed at a high level, there is a fine balance between risk and reward. The genuine fast bowler always walks a tightrope between the exceptional and the dangerous. The human body can only tolerate so much force.

There are four main rotational nodes in fast bowling and javelin throwing:

-

- Pivot turn on BFC, allowing extension of the front leg—more for a knee-dominant fast bowler

-

- Hip shoulder separation prior to FFC

-

- Trunk rotation on delivery

-

- Shoulder rotation on delivery and follow-through

For all rotational sports/transverse plane skills like fast bowling, javelin throwing, and pitching, the understanding of sequencing from proximal to distal can be the difference between success and failure. In actual fact, it has to be a priority in your training program. The lack of kinetic sequencing, starting with a pivot/pre-turn at the back foot via an outside edge contact and into hip internal rotation and slightly delayed trunk rotation, accounts for a large amount of exit/ball speed/distance deficiency.

For all rotational sport skills like fast bowling, javelin throwing, and pitching, the understanding of sequencing from proximal to distal can be the difference between success and failure. Share on XThe best throwing athletes use the natural “catapult/sling” effect of the fascial system in the body. The anterior oblique subsystem (AOS) is key to rotational movements in sport. What is it?

“The muscles that comprise the AOS are the global movers of the anterior trunk and the adductors. This subsystem plays a significant role in stabilizing the thoracic and lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint (SIJ), pubic symphysis and hip, as well as transferring force between lower and upper extremities. The AOS plays an active role in all pushing and rotational movement patterns (especially turning in), multi-segmental flexion, and eccentrically decelerating spinal extension and rotation, as well as hip extension, abduction and external rotation (knees bow in and excessive forward lean). The AOS is the functional antagonist of the Posterior Oblique Subsystems (POS)” –Brookbush Institute

The kinetic chain in overarm throwing/bowling is initiated by the heavy proximal segments (the trunk) followed by the lighter distal segments (the arm segments), resulting in the distal segments rotating faster than the proximal segments.3

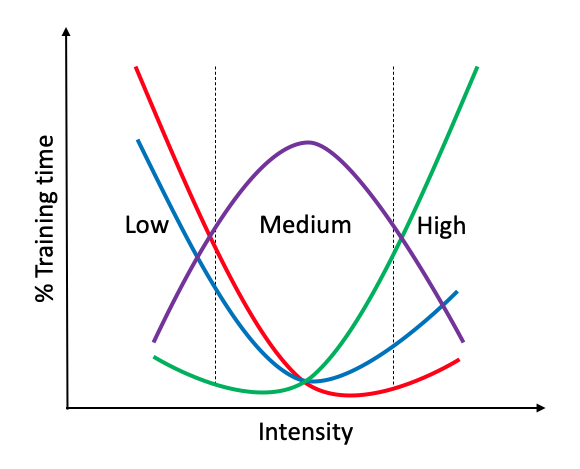

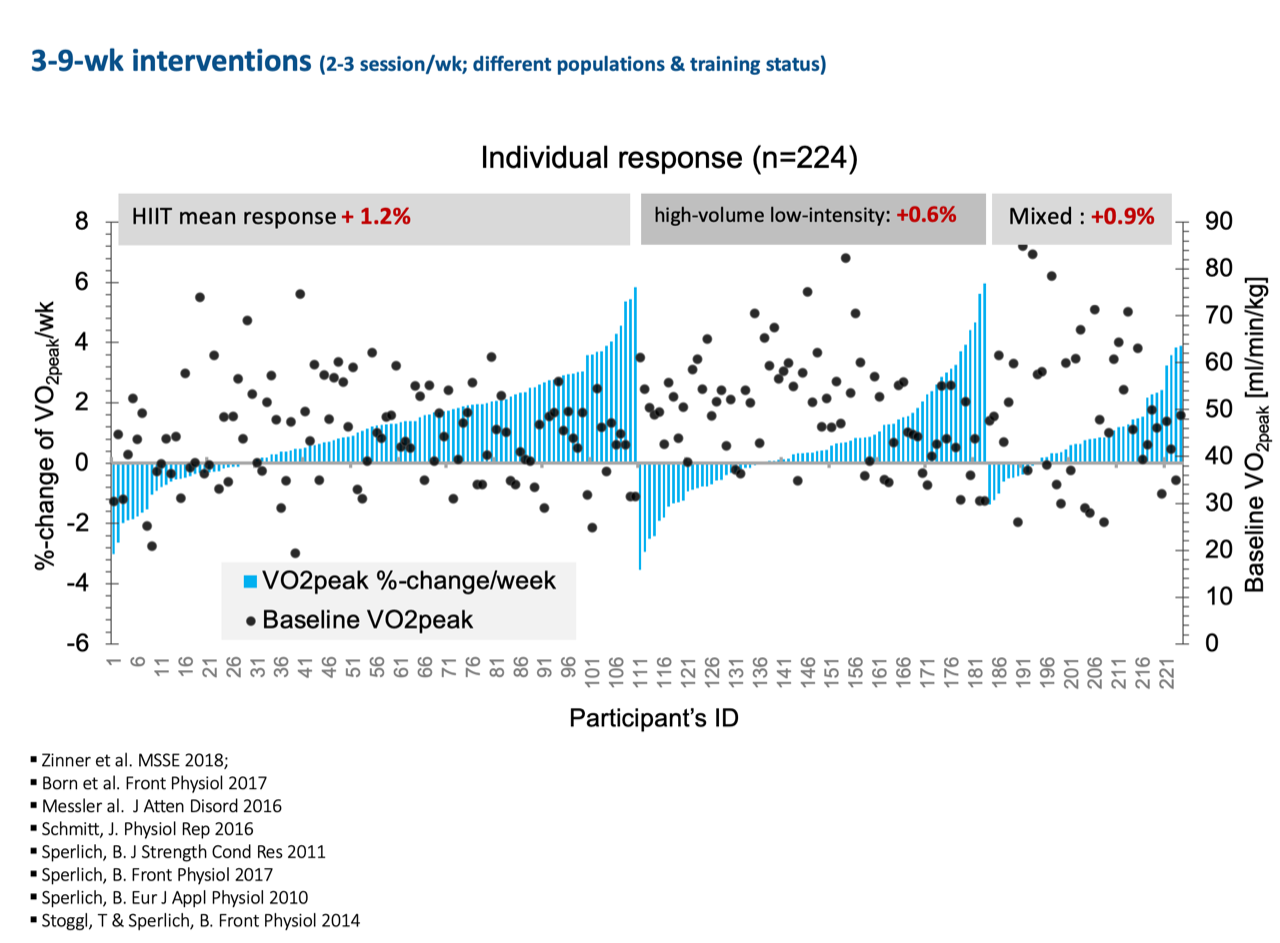

Based on data taken from Catapult GPS and rotational 1080 Sprint exercises, the majority of fast bowlers have similar trunk rotation speed. Most are above 1,600-2,000 rpm, which is around 6,000-7,800 degrees per second. Converted to linear momentum, this is around 20-30 m/s. This also highlights my belief that nothing in the confines of a gym will ever replicate the skill on the sports field. Specific preparation exercise like a rotational medicine ball throw may reach 5-7 m/s. This why you need to perform the skill itself in variety of ways, underloaded or overloaded, to guarantee a true transfer of training.

However large these speeds are, most bowlers achieve them, within reason. I believe if it’s more than 1,000 rpm, then rotational power is not your limiting factor. If it isn’t, then you need to focus on improving it.

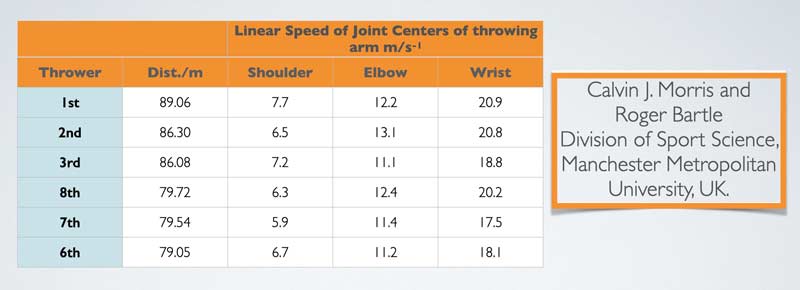

The figure below is based on a study of javelin throwers that identified the distance of the throw correlated with the more distal segments of the sequence. Approach speed, momentum in front foot block, technique, and trunk rotational speeds were similar on all throws.

Toyoshima et al., in a study published in Biomechanics IV, demonstrated that 46.9% of the velocity of the overhand throw could be attributed to the stride and body rotation, with 53.1% due to arm action. So, it’s essential we isolate the upper body and train it explosively, as well as trunk rotation and hip shoulder separation.

Arm speed/release speed is key.

“Inspection of the table shows that the major differences in techniques between throwers occur in the more distal segments. For instance, the peak right shoulder joint linear speeds vary within a range of 1.8 ms. For the right elbow and wrist joints this range increases to 2.0 ms and 3.4 ms respectively. It would seem to be in the latter stages of the deliver)’ that the biggest distinction in the techniques of these throwers are evident. This is not surprising when one considers that over 60% of the javelin release speed generated by the gold medallist was achieved in the 60 ms immediately before release.” –Morris and Bartle

Based on recent research, I firmly believe that ball velocity correlates with “finger release speed.” This is a new measurement from Motus Global, and I think it’s a key performance indicator.

Arm speed has a positive correlation with ball velocity. As you grow, arm speed will decrease due to longer levers. However, the key is maintaining arm speed, as Dr. Fleisig’s study highlighted. Arm speed may be less, but torque (rotational force) is higher. The older you grow, the bigger the segments!

The key is to highlight whether the thrower needs more strength or more speed. Do they need to bowl more lighter balls/spears or heavier balls/spears? Take them to the other end of the continuum to improve their weakness while respecting their strengths.

Performance Relies on Good Biodynamics

I’ve hopefully provided a validation for my theories and methodology in coaching throwing athletes. In particular, fast bowlers in cricket. The key message is that good biodynamics underpin performance, which is determined by the stabilization, separation, and orientation of key attractors sites in the sequence. Both technique and physicality are essential for throwing athletes, so focusing on one over the other will ultimately lead to suboptimal performance and failure.

Both technique and physicality are essential for throwing athletes, so focusing on one over the other will ultimately lead to suboptimal performance and failure, says @SteffanJones105. Share on XThis is why I adhere to what James Smith refers to as the “governing dynamics of coaching.” You need the knowledge of all aspects of human performance to truly have a positive impact on the ultimate aim of transfer of training.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Kraaijenhof, H. Methodology of Training in the 22nd Century: An Updated Approach to Training and Coaching the Elite Athlete. 2019. Ultimate Athlete Concepts.

2. Chu, S.K., Jayabalan, P., Kibler, W.B., and Press, J. “The Kinetic Chain Revisited: New Concepts on Throwing Mechanics and Injury.” PM&R. 2016;8(3):S69-S77.

3. Smith, J. Speed Strength: A Comprehensive Guide to the Biomechanics and Training Methodology of Linear Speed. 2019.

4. McNally, M.P., Borstad, J.D., Oñate, J.A., and Chaudhari, A.M.W. “Stride Leg Ground Reaction Forces Predict Throwing Velocity in Adult Recreational Baseball Pitchers.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2015;29(10):2708-2715.