In Olympic weightlifting, a strong and stable front rack position can make or break a successful clean and jerk attempt. From the moment the bar is received in the clean to the drive in the jerk, the bar is active in this position on the “shelf” of the athlete. You can look at 10 different athletes, and they could all have a different front rack position. This isn’t wrong; it is practical for their biomechanics. The difficulty of the position is what allows for its variability. The front rack position is unique and individualized to an athlete based on many variables:

- Past training history

- Biomechanics (extremity length/ratio)

- Positional strengths/weaknesses

- Soft tissue limitations

- Possible injury history

- Previous sports background

The front rack requires a lot of mobility from the trunk and upper body. Whether you coach Olympic weightlifters or incorporate Olympic-based movements (especially cleans) into your training program, it is important to understand what a good front rack position is and work through issues that could prevent your athletes from achieving this. We’ve all seen the athletes who struggle with this position: the athlete whose thoracic spine is flexed so hard they look like a turtle, trying to pop out of their shell, standing up a front squat; the athlete who can’t seem to get even one finger wrapped around the bar to secure it; and the athlete who is so tight they can’t even get the bar to rest on their deltoids, leaving the bar out in front of them.

You can look at 10 different athletes, and they could all have a different front rack position. This isn’t wrong; it is practical for their biomechanics, says @nicc__marie. Share on X

In a good front rack position:

- The hands should be placed outside of the shoulders.

- The shoulder should be externally rotated.

- The thoracic spine is in extension.

- The scapula is slightly elevated and protracted.

- The barbell should rest on the notch of the anterior deltoid.

With all of these elements in place, your body will create a shelf for the barbell that is supported by your trunk.

Video 1. This tutorial highlights a good front rack position that athletes should strive to achieve in an optimal front rack.

In this article, I want to take you through some of the common issues seen throughout the front rack and how they can affect the lift. I will look at the three main movements that utilize the front rack: the front squat, the clean, and the jerk. In each of these, the position is slightly different to gain optimal execution of the movement.

The Front Squat

The front rack position for a front squat uses the narrowest hand placement of the three lifts. The height of the elbows is at the highest point allowed based on an athlete’s mobility. Due to the hand position and height of the elbow, the athlete may have a more open palm, with the bar resting with anywhere from 2-5 fingers wrapped around it. The height of the elbow is important to keep the bar from dumping forward and the t-spine from flexing or “rounding.”

This excessive rounded posture can be due to a lack of mobility or lack of strength. How do you know if it is a mobility issue or if it is a strength issue? When a new athlete walks into the gym, we begin our assessment by observing their posture, gait, and how they stand naturally. Our assessment is designed to observe the athlete’s movements that show various degrees of mobility and movement capability.

One of the first things to look at is how their t-spine responds in overhead flexion. I like using the Supine OH Flexion to see if their ribs will flare when they bring their arms overhead. If they do, then we can start to focus on some mobility to open up the t-spine. If the athlete remains neutral, then we move to a floor slide in order to see how their t-spine responds when the shoulders are in external rotation.

In this day and age, the vast majority of the population has a tighter t-spine from endless hours of poor posture while staring down at a cell phone or working at a desk all day. This kyphotic “cyber posture” is an unhealthy pattern for the spine and can lead to other muscular compensations and issues in daily life. For Olympic weightlifting and the front rack position, it is detrimental.

Some ways to address mobility issues require opening the t-spine up in extension and rotation. The Mini Band Supine OH Flexion is one of my go-to exercises to use during an assessment and for movement prep—this focuses on lengthening the lats, but also reveals if the athlete is limited in their range of motion (ROM) because of their t-spine. If they can’t keep their low back connected to the floor as their arms move overhead, we know that we need to focus more on mobility.

The Quadruped T-Spine Rotation helps to improve rotational mobility. Based on the athlete’s ability to get their elbow to the ceiling, we can see if there is a discrepancy in mobility from one side or the other. Even though asymmetries are not a reason to change everything, we do want to be aware of them and make sure they are not so severe that the bar appears crooked when being held in the front rack position.

A poor kyphotic posture will not only make it difficult to hold the bar in a good position but will also be problematic once load is added to the bar. For an athlete with severe flexion or rounding of the t-spine, as the weight gets heavier, they will no longer be able to keep their hips underneath their torso—and they will try to drive out of the bottom of a squat. As the hips shoot back on the ascension of the squat, the roundedness of the shoulders and t-spine push the bar away from the athlete’s center of gravity, and if it is heavy enough, the bar will inevitably fall forward. When we see this start to develop based on the load of the barbell, we know the athlete lacks strength in the front rack position.

A poor kyphotic posture will not only make it difficult to hold the bar in a good position but will also be problematic once load is added to the bar, says @nicc__marie. Share on XA strength concern requires us to not only look at upper back strength, but anterior core strength as well. Front rack bias aside, we want our athletes to stand with good posture because it supports spinal health (and every athlete needs a strong and healthy spine). Using a variety of KB or DB goblet holds can help to strengthen some smaller upper back muscles and allow the lats to not overcompensate in the front rack position. KB Goblet Hold Hinges, lunges, and squats are great for movement prep and supplemental accessory work. When looking at anterior core strength, deadbug/crawl/contralateral variations should be a staple in any training program.

Video 2. One variation that is more specific to Olympic weightlifting is a Banded Lat Pull Deadbug. This movement allows for lat engagement while challenging the anterior core.

There are benefits to programming the front squat in training for non-weightlifters. The load of the barbell puts less compressive force on the knee versus the back squat. Depending on an athlete’s biomechanics, the alignment of the torso and depth of the squat will vary. Athletes with longer femurs will have a slight lean in the torso to help them find parallel.

Remember, there is a difference between a lean of the torso and flexion in the t-spine. The torso position in the front squat places less strain on the spinal erectors. Along with anatomical benefits, the position of the barbell on the front rack places more emphasis on the anterior abdominal muscles.

The Clean

If you can’t front squat it, you can’t clean it! If you are unable to perform the catch position of a clean from a static position (i.e., unrack the barbell), then it will be all but impossible to do so dynamically as you transition under the bar into the receiving position. If you are a strength coach who incorporates clean progressions in the weight room, I strongly urge you to have your athletes front squat in the front rack position. Being able to front squat using a true front rack will build strength and stability to support the absorption of the barbell onto the chest and anterior deltoid of the athlete safely and efficiently in a clean.

If you’re a strength coach who incorporates clean progressions in the weight room, I strongly urge you to have your athletes front squat in the front rack position, says @nicc__marie. Share on XThe front rack position for a clean is slightly wider than the front rack position for a front squat. The purpose of the slightly wider grip is to allow the humerus more external rotation to create a wider “shelf” to receive the bar. A wider hand position will lower the elbows more than in a front squat, but they should still be through the bar and up as much as ROM will allow. This also allows the athlete to have a better grip on the bar in the turnover and catch position.

Common issues we see in the front rack of the clean occur during the third pull of the lift and in the catch position. During the third pull, the athlete pulls their body down to meet the barbell and move into the receiving position or catch. If the athlete pulls down faster than the height of the barbell, the barbell crashes onto their chest. When the barbell crashes onto the athlete, it can either spit the athlete out behind the bar, crush their anterior core on impact, and miss forward or—best-case scenario—give them some really nice bruises to show off to friends. In either case, as coaches we want none of the above for our athletes.

The argument for strength coaches to perform power cleans is to help their athletes absorb and decelerate heavy loads, but if the barbell crashes on an athlete, then we don’t get the desired effect. This crash can occur because of a timing issue or a technique issue.

If the barbell crashes due to poor timing, then the athlete is unaware of the barbell’s trajectory. The second the athlete tries to pull up too much with their arms instead of pulling themselves down into the catch, there is a disconnection with the bar. If the bar crashes due to a technical issue, we will see the bar loop out away from the athlete and crash onto their sternum as it comes down.

In order to assess whether it is a timing or technical limitation, you have to watch the athlete and their bar path as they move through the clean. If the timing is off, there will be a clear moment where the athlete drops under the bar—rather than meeting the bar in that moment, the athlete drops and then the barbell hits their chest. In this instance, the athlete does not fully understand where the barbell is in space and how much force their body needs to produce to get the most out of the lift.

It is imperative that the athlete understands where the barbell is throughout the transition of the lift, and the best way to do this is to maintain a hook grip around the bar as long as possible. Athletes who can hook grip the bar in the front rack, although it’s somewhat less common, demand and have a great deal of wrist mobility. For the vast majority, the thumb will slide out but still stay wrapped around the bar, and the fingers will open up. The longer you can maintain your hook grip in transition, the more in control of the barbell you are. Wrist Rockers are a great way to improve wrist mobility and lengthen the muscles in the forearm, helping athletes maintain a fuller grip on the bar through transition and into the catch position.

If the bar loops out away from the body, we have a more technical issue occurring during the first or second pull of the lift. For the sake of this article, I will focus on the technique from the second pull. We often see this when an athlete doesn’t have an aggressive high pull action of the elbows as they transition under the bar. If the elbows shoot back to the wall behind them versus up to the ceiling, the bar will loop and almost look like they are performing a bicep curl to receive the bar.

It is vital that the athlete understands where the barbell is throughout the transition of the lift, and the best way to do this is to maintain a hook grip around the bar as long as possible. Share on XAnother strength exercise I use is the Clean-Grip High Pull. This movement is different from a clean pull, where the arms remain straight the entire time. An article I wrote, “To Bend or Not to Bend?,” further explains this point. The emphasis of a clean pull is technique and leg drive into triple extension. A high pull places more emphasis on having aggressive elbows as your body drops under the bar, which coincides more with the third pull of the lift after the athlete has hit triple extension.

Video 3. Pull Unders are a technique drill that can help reinforce the arm movement during the third pull of the lift and, coincidentally, will also help with timing to meet the bar.

Another issue we often see in the front rack of the clean is that the bar never actually touches the athlete’s chest. We’ve seen those videos where the athlete grinds out of the bottom of a clean with their elbows pointing straight down the floor and the barbell 2 inches away from their body. When athletes have this issue, they complain their wrists are the problem. Of course your wrist hurts—you have one of the smallest joints of your body trying to support a barbell with no help from the trunk! This becomes even riskier because if an athlete can’t maintain a front rack and get their elbows through and up into the receiving position, then the elbow can crash onto the knee, and that impact can lead to severe wrist injuries.

Although the wrist is in discomfort and should be addressed to avoid pain, the issue more likely comes from tight lats and a tight t-spine. Soft tissue work and mobility are key here, and then once you’ve mobilized, be sure to move the muscles through their new ROM in order to create a lasting effect on mobility. One movement I like that emphasizes the elongation of the serratus and teres minor is a Banded Scapula Reach. This reinforces moving the arm with the shoulder blade instead of the humerus to get more movement in the t-spine. To build some strength in the wrist, consider bottom-up kettlebell movements such as presses and carries. One exercise I use that involves the t-spine as well is a Bottom-Up KB Waiters Carry.

The Jerk

“The clean is for show, the jerk is for the dough.” –Phil Sabatini

In competition, it doesn’t matter how strong the clean is if your jerk can’t deliver in the end. There are two jerks commonly performed by American weightlifters: the split jerk and the push or power jerk. Check out this video to better understand the difference between the split jerk and the push jerk:

- In a split jerk, the legs move outward from the hips into a split squat position.

- In a push jerk, the feet stay bilateral as the hips pull down into a quarter squat.

The majority of athletes in competition perform split jerks; however, push jerks are still very much a part of their training to help improve bar path in the drive phase of the jerk. There is much less room for error and horizontal translation of the barbell in the push jerk. If you have an athlete who tends to push the bar out and away from them during the drive, this is a great movement to help them better understand a more vertical bar path.

If you have an athlete who tends to push the bar away from them during the drive, the push jerk is a great movement to help them better understand a more vertical bar path, says @nicc__marie. Share on X

Regardless of which jerk the athlete is training, the front rack position is the same. The jerk is the widest of the three grips. The elbows are lower, but still through the bar at about a 45-degree angle. The external rotation of the shoulder is almost overexaggerated to support that barbell through the dip and drive of the lift. If an athlete has trouble externally rotating the shoulder in a wider grip, then we want to incorporate soft tissue work with a lacrosse ball and windshield wiping the arms to open up the pecs and anterior deltoids of the shoulder. Once you’ve gained some release through soft tissue, we want to work the muscle through the new range of motion. A doorway pec stretch or a banded distraction is a great way to facilitate this movement.

As an athlete stands up a clean and resets for the jerk, take notice of their spine. Are they able to maintain a neutral lumbar spine, or do their ribs have to flare out? Another mobility issue we often see in the jerk is hyperextension in the low back because, again, the t-spine is too immobile to support the barbell without creating a compensation in the low back.

It is important when working through t-spine mobility to emphasize keeping the rib cage tucked. This will allow the athlete to feel a more neutral low back position and understand that when the ribs flare open, the low back hyperextends. Deadbug variations can help to clean up this movement pattern by feeling a neutral low back on the floor while keeping the ribs closed on the anterior side. If they lack a strong trunk position, the front rack will be compromised—and without a strong front rack to support the barbell, the phases of the jerk become much more laborious and difficult to complete with technical proficiency.

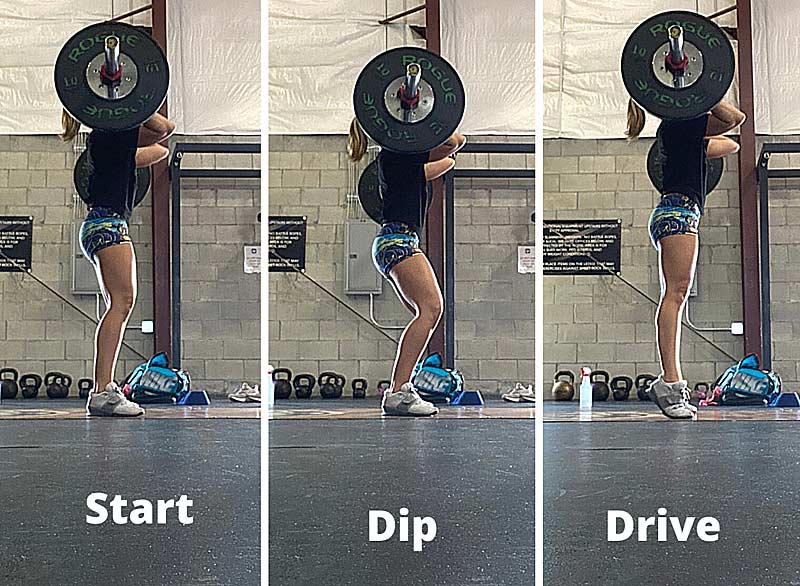

After addressing positional issues, we want to make sure the front rack is not limiting the actual movement sequence of the jerk. Disconnection in the dip occurs when the athlete transitions into the dip phase of the jerk, and the barbell bounces off the shelf. When this happens, the path of the barbell is compromised. As the athlete transitions into the upward drive phase with a disconnected bar that is being pulled by gravity, the athlete has to fight through to try and get the barbell overhead.

The barbell should move in unison with the athlete. This disconnect often occurs when the anterior core collapses in the dip and the shoulders fall forward. Jerk Dip Holds are a technical exercise that reinforce a quick descent into the dip while controlling and maintaining stillness of the barbell and elbows in the front rack. The spine should be in a neutral position, the trunk braced, and the elbows don’t move from their position.

Video 4. Jerks with a pause in the dip are another way for an athlete to focus on keeping the elbows still and maintaining a good bar position from the dip into the drive.

In Your Weight Room

A strong front rack position—whether in the front squat, clean, or jerk—can give athletes comfort in knowing the barbell is properly supported through all phases of the movement. Athletes will come in and out of the gym with varying issues of mobility and strength, and as coaches we need to understand the movement sequences of an athlete and how we can best address any limitations those may present. It is our job to help our athletes find the delicate balance between mobility and strength. If an athlete lacks mobility in a given area, that will lead to compensations in other areas of the body. On the opposite side, as much as we want our athletes to be stiff, too much stiffness will take away their ability to absorb and produce force.

A good front rack position allows athletes to build isometric strength in the upper body as well as the trunk and core, says @nicc__marie. Share on XA good front rack position allows athletes to build isometric strength in the upper body as well as the trunk and core. The better the front rack position, the more stacked the torso is to not only control the load of the barbell, but to further improve core control and stability. As the great Stu McGill says, “Proximal stability allows for distal strength and speed.”

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Excellent article – keep up the good work….you are special and know what you are doing and you are so dedicated to your position.