[mashshare]

After 20 years of scientific research, we are closer to knowing how isoinertial training works, but we are not much better at knowing how to plan training sessions. Some studies have done a great job of comparing flywheel training, a type of isoinertial resistance, to conventional training, but they have not presented anything in enough detail to satisfy the practitioner. This article is not about just a single approach; it’s about learning to use flywheel training in a way that is meaningful and purpose-driven.

The Most Common Errors In Flywheel Training

While not truly a mistake or error, the most common approach to flywheel training is to replace exercises done on the ground with a flywheel alternative. While swapping modalities that are similar makes sense on paper, contractions are not about visual similarities. Instead, they are about the roles and needs of preparing the body based on the inevitable calendar of training and competition.

Just adding a few sets of popular #flywheel exercises like a dash of salt isn’t great programming, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XSwitching a barbell back squat with a flywheel squat isn’t a pure replacement, and just adding a few sets of popular flywheel exercises to a program like a dash of salt isn’t great programming. Based on common patterns of use, most of the approaches we have seen with flywheel integration are:

- Add in a few exercises at the end of a conventional program as a finishing option.

- Replace traditional exercises like barbell or bodyweight movements with flywheel variants.

- Add a flywheel phase of training with a heavy concentration of isoinertial training.

These approaches aren’t foolish, and we have experimented with similar tactics, but we can do better. The No. 1 issue with any modality is that the best coaches usually have very little bias towards any method, as they simply want what is effective.

What we rarely see are long-term records of research-grade measures of real athlete training. Most of what we see in the research are general populations or short intervention studies; nothing replicating a four-year development plan for serious athletes. Coaches need science, but they also need complete history or record-keeping for the big, integrated picture. Science is our best tool, but don’t underestimate that interpretation of the science has even more importance because reasoning is what makes knowledge useful.

With the errors above in mind, we will show how you can modify training to integrate flywheels without the mistakes that are commonly made in programming.

Don’t Think Movements, Think Contractions

The functional training craze of the late 1990s did have value—it made us think of what the word “function” really meant. Mimicking sport by recreating similar motions isn’t functional or sport-specific: it’s usually just a really bad attempt to combine weights and athletic motions. We have seen countless exercises come and go, while other exercises seem to linger longer. Shadowboxing and running with dumbbells are still popular, but so far nothing in the research shows either is the magic bullet. When thinking functional, don’t focus on what the exercise looks like, appreciate what the training gives you back.

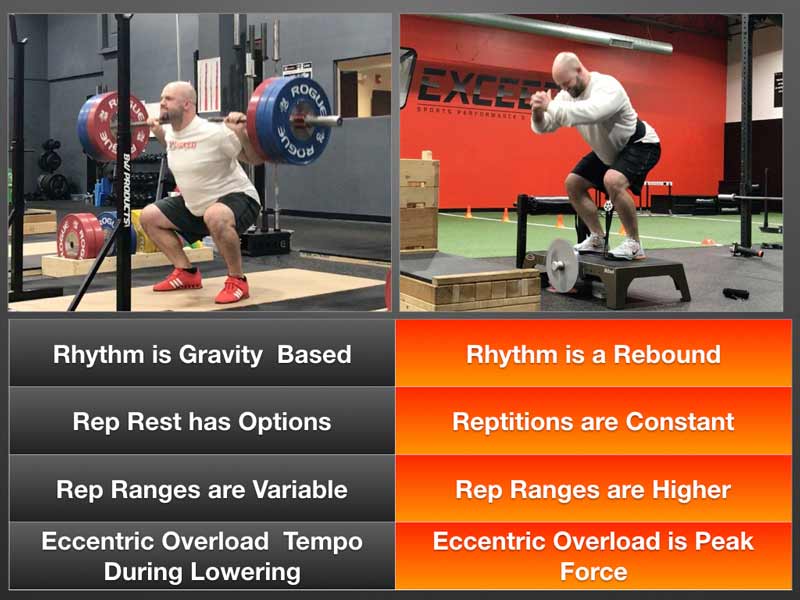

When selecting exercises, it makes sense to think about the mechanics of the movement, but the contractions are still different than traditional barbell or bodyweight motions. It also makes sense that a similar exercise of the same “species” will be a logical exchange, but the way flywheels work, some adjustments to the entire program are necessary. For example, if you take out barbell back squats and switch them with a platform flywheel, the result is much different.

- Barbells can do low or single rep ranges; flywheels need starter reps to initiate full isoinertial reps.

- Between repetitions barbell options allow rest, while flywheels are constant effort contractions.

- Flywheels have high inertia immediately during the descent of exercises, barbells don’t.

- Using a waist belt reduces overall spinal loading, which is a popular rationale for coaches who need that requirement.

We could go on, as there are more differences than those listed, but the swapping out of an exercise is not a pure exchange. There are enough differences that coaches must make more changes than just the exercise name on the workout sheet. The No. 1 takeaway is that swapping out an exercise usually has a ripple effect in training. This means that you might have to adjust other parts of training during and after the sessions to accommodate the differences.

The No. 1 takeaway is that swapping out an exercise usually has a ripple effect in training, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XHow to Use the Molecular Signaling of Flywheels

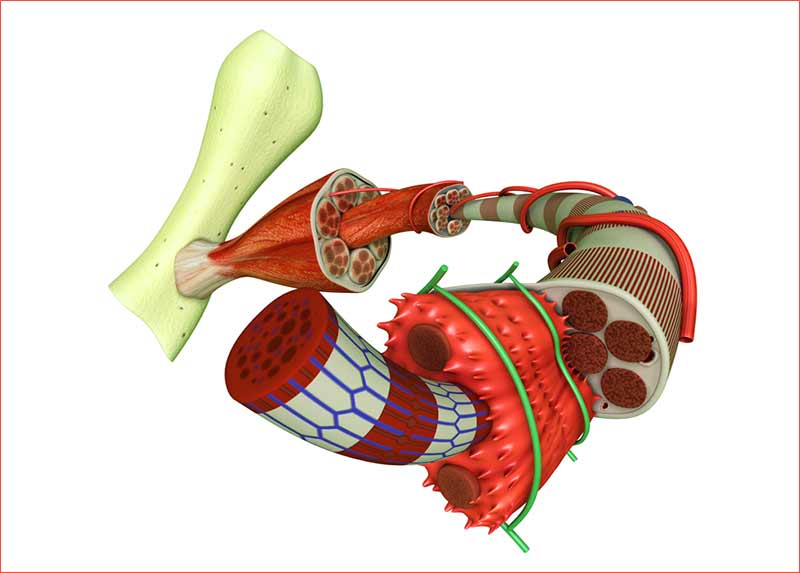

We could name a few coaches that hate the concept and even the word “finisher,” but tacking on a few sets at the end of a training session isn’t the end of the world, and does have some benefits. Training is tough physically and mentally, and just a little dessert here and there isn’t going to ruin someone. This article briefly mentioned the idea of using flywheels and finishing a workout with isoinertial training, but it’s more than just doing a few sets of an exercise at the end of a workout. It’s about the molecular responses.

What we know about molecular signaling and training is that low loads and high repetitions can stimulate both strength and size. Some current unfounded fears over having the wrong morphological changes are that the specific muscular adaptations from lower loads increase the wrong type of hypertrophy. Simply stated, high reps theoretically build less-favorable changes to the tissues for athletes because it’s just “body builder” muscle and has a poor power-to-weight ratio.

At the molecular level, flywheels may be the most potent way to increase muscle’s strength and size. Share on XTo date, research has not shown conclusive evidence, because nearly every training program has maximal effort bouts in the workouts. Blood flow restriction training maximizes high repetition training, and flywheels tend to be higher repetitions as well. At the molecular level, flywheels are likely the most potent way to increase the strength and size of muscle.

Theoretical sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar hypertrophy debates have been going on for years, but we don’t think it’s a concern if the concept is proven true. Remember that the discussion is about the singular and pure modes of training; meaning the difference between a full-time bodybuilder and a full-time power lifter, not an athlete using mixed and multiple methods. In theory, so much of the training is one style of lifting that the long-term training effects should induce clear differentiation. We don’t see classification of athletes based on sport (powerlifting versus bodybuilding) now as much as we did in the earlier hypertrophy research because many athletes overlap their training programs.

Most of the training of flywheels is eccentric enhanced power and strength development, due to the load and speed of the contraction. The research concludes that hypertrophy from flywheel training is very potent, and we have witnessed exactly what the scientific investigations claimed—rapid changes in cross-sectional area or CSA. While training for muscle mass isn’t a direct way to get faster or decelerate safer, many athletes that we inherit have atrophy from injuries and we need rapid changes to get them ready for another year of competition. There’s a growing need to fix muscle groups that are legitimately shut down due to non-use, abuse, or lack of proper rehabilitation. Poor development of youth sport athletes by selfish coaches is the cause of this problem.

In theory (but supported by enough research to make a case for flywheels), if you want to send a very strong message to the muscles of athletes, use flywheel training because it combines multiple factors that target the molecular pathways to grow and get stronger. The moderate load, constant tension, and depletion style sets are the reasons we add one or two exercises at the end of training. We adjust our program, not by decreasing volume, but just scaring the athletes into being receptive to getting more sleep and taking responsibility for their diets. Flywheel training isn’t for everyone and that is a good thing. Athletes need to deserve it first, by making the sacrifices and commitment necessary to recover from it.

The Keys to Constructing Concentrated Eccentric Phases

The terms “block” or “phase” get kicked around easily, but for real adaptations to occur, a signal to change the body must be clear, intense, and frequent over time. A soon as a phase ends, detraining effects of that adaption will occur unless it’s sustained by a signal that is either the same or very similar. Debates will never end on which are the best roads leading to Rome, but it’s easy to determine success. Mechanical strength and structural length are two near bulletproof measures that determine the success of an eccentric program. While ultrasonography measures are not easy to capture, we do know that specific exercises elicit the changes we all need for athletes. Neuromuscular strength is direct and easier to see trend, as all it takes is a workout session to evaluate.

Heavy eccentric training is brutal on the body, and recovery from that type of resistance requires time. Additionally, eccentric training is very selfish, meaning not a lot of resources are available to develop other qualities needed in sport success. Hence, eccentric training isn’t the ideal way to build athletes in modern sport when the checklist already has so many much-needed items to develop. Realistically, eccentric overload time periods are sessions rather than months. As few as three weeks are enough make serious changes to the neuromuscular system. About 10 to 12 aggressive sessions that push an athlete will make all the difference for a season, and improvements can reap benefits later if you continue the training in a reduced fashion.

A phase of training should never require more than a few days of #recovery, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XWith added eccentric training comes muscular, and sometimes tendon, soreness. Incremental loading and careful monitoring are essential or the result is just a tired and beat-up athlete. We have yet to see an injury from eccentric training when loads are based on reasonable adjustments, but we have seen plenty of athletes stagnate (including our own) from “too much, too soon” loading. Exactly how much overreaching happens with eccentric training is unknown and will vary from program to program, but a phase of training should never require more than a few days of recovery.

We have been very liberal with nutritional practices, meaning we don’t try to have an athlete decrease their body fat by reducing caloric intake during eccentric training phases. During the winter offseasons for football or late fall and early summer breaks for soccer, we don’t stress about athletes not being strict with their diets. It’s not that we allow poor eating habits, it’s just that we would rather have more work to do later when we have conditioning than make the mistake and under-recover them because we had insufficient calories too early. Eccentric training has no reported research that claims extra protein or nutrients are necessary, but we don’t want to make the mistake and not have enough. We can’t go back and fix the problem, but we can address body composition more easily and manage it immediately.

The recovery support, or what we provide athletes with, during heavy eccentrics are hydrotherapy, EMS, and some massage. Even if an athlete just tacks on a few sets of flywheel training at the end of a program, it’s enough to warrant an adjustment to the recovery side or low-intensity parts of a program. Some will argue that we should save recovery for later periods, but we care about deeper preparation levels with strength so we can train harder mechanically.

Physiological fears of blunting recovery internally are more for cryotherapy, an approach that should be for peaking periods. Besides time and soreness, be vigilant for residual fatigue and emotional darkness (poor willingness to train or worse). Athletes will lose their drive and motivation when training during heavy periods, so don’t just look at training data.

Progressive Overload with Flywheels

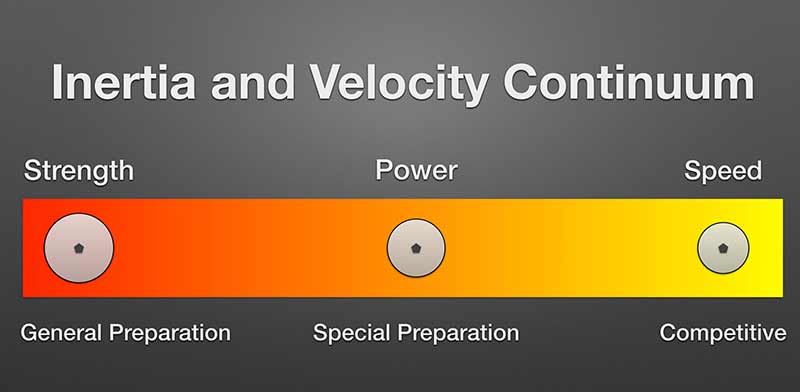

The most difficult juggle with loading is how to progressively overload an athlete with isoinertial training. Increasing demands from flywheels are a juggle of three variables: rotational speed, weight, and diameter size. Simply adding more flywheels will not necessarily mean an athlete trains with higher intensity, as concentric forces initiate the momentum and effort drives everything. The amount you can drive down into the platform is the overload you receive. It’s essential that you understand that the size and weight of the flywheel is less important than how you receive the load and how much speed you can put into the machine.

Similar to VBT (velocity based training), flywheels share overlapping concepts of speed and loading, and it’s vital that coaches using isoinertial training know how to manipulate training variables and progress athletes. Four primary variables exist with flywheel overload, and a few sub-variables help shape the details of programming those four.

Inertia Resistance: Force and power are fine summaries of the inertia, and they are calculated by flywheel sensors, such as the kMeter. The assumption that a heavier flywheel disc will create a higher resistance is only partially true. The kMeter solves the quantification of inertia resistance for both coach and athlete.

Contraction Rate: No scientific investigation has drilled down to the F-V curve and how flywheel load and programming create a transfer, but faster eccentric and concentric actions are different than slower movements. Higher velocity contractions may fatigue the faster fiber types, so monitoring training for the quantification of flywheel training is paramount.

Eccentric Reception: How the body receives the load determines how the eccentric overload creates an effect on the body. Just training with a flywheel alone provides a rapid early eccentric overload, but the technique of absorbing the forces dictates how much overload and where you or your athletes receive the stress. It’s easy to visualize two legs pushing up while one leg absorbs the force; it’s harder to visualize an athlete falling with the weight and stopping abruptly at the bottom. Exercise selection and technique are essential in the way eccentric overload stimulates adaptation.

Total Work Performed: Volume, and the distribution of type of work performed, is a factor to how athletes will adapt to, and recover from, flywheels. While there are some theories about the way successive bouts of training will impact later reliance on eccentric load, based on our experience and some research, the body becomes more able to handle strain over time. Distribution of work, meaning how much of it was at higher velocity, should influence the power or strength adaptations of isoinertial training.

Clearly, like the laws and principles of conventional barbell training, there is more to flywheel overload than just slapping another disc on the machine. On the other hand, be confident that you will be able to find better progressive overload approaches than sets and reps alone with experience. More training factors make up progressive overload, but the four variables are enough to be competent with flywheel loading.

Isoinertial Overload Periodization and Programming

Planning a season with flywheels can sound like a big task or something that requires a complex map of training. The reality is that, because flywheel training is a part of the big picture, the amount of changes and adjustments should be only enough to make sure things run smoothly. Over the course of the article, we reviewed that making a few quick additions or changes is not as simple as changing exercise names, but we don’t want you to perceive it as doing brain surgery.

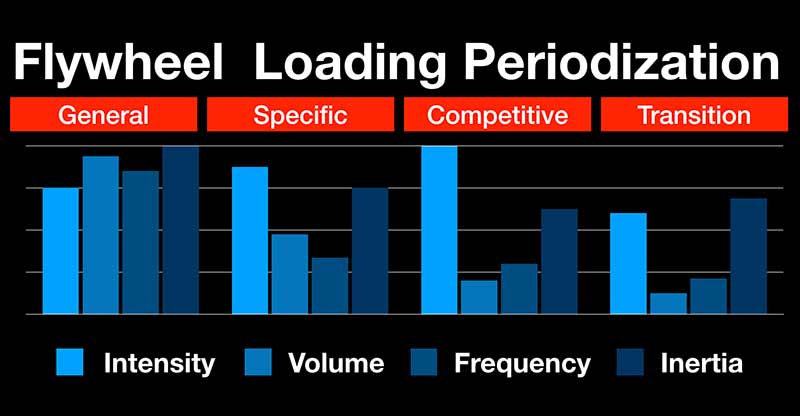

The simplest way to look at planning the season is to think about how much and when you compete and how much you focus on training. With the lines between offseason, preseason, and competitive season blurring more and more, it’s harder to label any phase GPP, SPP, and Competitive. Even if a phase is just a few weeks long, still obey the laws and principles of sports training and plan accordingly. Here are recommendations based on standard training principles and the specific needs that flywheel training require.

GPP: The furthest away from the competition period is sometimes called the offseason, and it’s imperative that most of the gains of eccentric overload are done during this time period. Longer seasons mean shorter preparation times so, on the record, we include isoinertial training with any serious athlete in some fashion in the GPP. During the offseason our volume and flywheel load is at the highest, but speed or revolutions per minute are not maximal like later in the season. Overall, the load of the flywheel isn’t as important as the effort and volume of the athletes using it.

SPP: Typical pre-seasons in team sport are short, so while the phase deserves its own set of guidelines, it’s not very long in most scenarios. Blending qualities in order to transition into competing is the No. 1 approach we see in sports performance, and it’s certainly the case with flywheel training. During this time period, we increase the intensity with the overall training and start slightly decreasing volume. The transition from off-season to competing is tricky, because most of the time we see team coaches and programs make jumps or dramatic changes, thus shocking the system and usually creating DOMS (delayed onset muscle soreness) that athletes hate. We have seen subjective and objective data over the season, and a decrease in late week soreness is significantly lower with the inclusion of flywheels.

CPP: The competitive phase is tricky, as most coaches see it as a time to maintain or allow a decay of capacity, like a detraining leak. Realistically, it’s hard to build a body when opportunities to train are minimal, but clever ways of microdosing intensity and manipulating volume do allow for small gains or preservations of sport power if done properly. We use relatively the same design as the SPP, but drop volume significantly twice. The first half of the season we drop sets by a third, and then drop frequency to once a week on the back half.

To summarize, the pattern of loading is quite simple and very conventional. Speed increases and volume and frequency decrease as the season progresses. The choice to manipulate the loading with flywheels or weight of the inertia is good on paper, but we don’t have enough seasons under our belt to determine if that variable is meaningful.

Experimentation and the Learning Curve

This article is not a blueprint on what do with flywheels, as our own experiences really only include a few exercises used judiciously before graduating to more comprehensive and refined strategies. Collectively, we likely only scratch the surface of what needs to be done in training, and that is the exciting part because there’s room to improve. We hope the article gave you a few immediate ideas of what to think about before you start with flywheel training, but it’s going to be up to your own efforts to fully exploit the benefits of a flywheel system.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]