Most of us who have been in the field of athletic preparation for a while are familiar with Vern Gambetta. For those who aren’t, Gambetta is a 40-plus year veteran in the athletic development profession. His experience has run the gamut in terms of levels (professional, Olympic, high school) and sports (baseball, soccer, swimming, track). Gambetta’s ability to keep things simple and help his athletes master the basics has made his insights and applications timeless.

One such application I’ve employed and adapted is the leg circuit that bears his name. He developed the Gambetta leg circuit in the mid-1980s as a tool to serve as a foundation for lower body training for all athletes, at all levels, at various points in their training. Leg circuits develop general strength and work capacity in the lower body for explosive, speed, and power athletes. These general qualities will form a foundation for more intense work in the future (i.e., absolute strength and plyometrics). As we’ll learn, the pace and progression of leg circuits (LCs) are key to developing local hypertrophy in the muscles, resiliency of the connective tissues, and efficiency of the vascular tissues.

According to Gambetta, the benefits of leg circuits go beyond horsepower and engine size; he has also employed LCs as return to play criteria in lower extremity injury rehabilitation. Share on XAccording to Gambetta, the benefits of leg circuits go beyond horsepower and engine size; he has also employed LCs as return to play criteria in lower extremity injury rehabilitation, bridging the gap between physical therapy and athletic preparation. The goal for athletes is to complete five full leg circuits uninterrupted, with elite performers clocking in at just above five minutes. Although this is rare, we are looking at 250 reps in that amount of time.1 From a practical standpoint, this makes complete sense, as the first load any athlete (or person, for that matter) should be able to handle is their own body weight in an athletic manner.

The Classic Progression and Execution

The Gambetta leg circuit consists of four exercises, performed in order:

- Squat

- Forward lunge

- Dynamic step-up

- Squat jump

Repetitions have three level distinctions—the mini, half, and full—that you can use as progressions and adapt to needs (think short-long spectrum here). The mini leg circuit consists of five reps in the squat, three reps per leg for the lunges and step-ups, then three squat jumps, and it serves as the entry point for leg circuits. The next level is the half LC, where repetitions increase to 10/5e/5e/5, respectively. The full leg circuit consists of 20 reps of the squat, then 10 reps each leg for lunges, the same for step-ups, and 10 squat jumps.

Gambetta views the full leg circuit as the standard and the pinnacle, if you will. For Gambetta, performance of the full LC for five consistent sets (no rest between sets) serves as the hallmark of an athlete’s general fitness and readiness to play, existing as a test and a goal.2

For Gambetta, performance of the full leg circuit for 5 consistent sets (no rest between sets) serves as the hallmark of an athlete’s general fitness and readiness to play. Share on XLeg circuits progress via a systematic increase in volume and decrease in rest intervals. The first session consists of three sets of the circuit with 30 seconds of rest between exercises and one minute between completion of each circuit. Each subsequent session calls for adding one more set of work, culminating at five sets after three sessions. If athletes can complete the circuits with proper technique and make the rest intervals, then the next session will start again with three sets with the rest between exercise eliminated but preserved between circuits. The final progression would be three, four, and five circuits without rest between exercises and circuits.

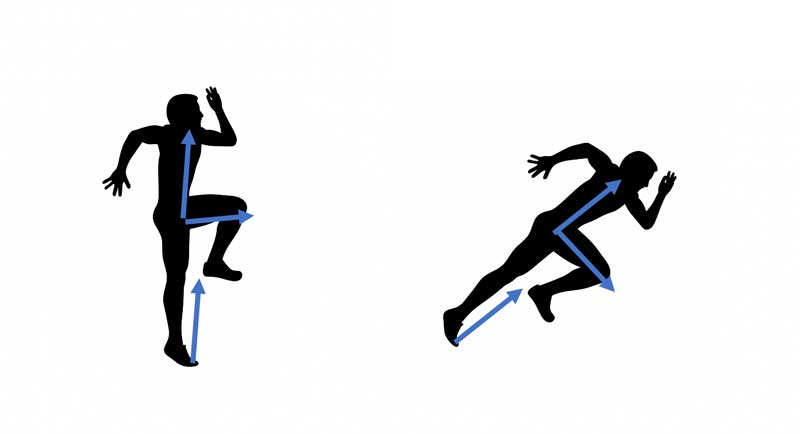

The key to the effectiveness of the leg circuits goes beyond sets, reps, and the volume progression. Gambetta espouses that the rhythm, tempo, and speed of the repetitions are key to mimicking the eccentric loads seen in practice, play, and higher intensity preparation. In my understanding, the fast-down/fast-up pace (with the goal of one rep per second on squats and one rep per 1.5 seconds on lunges and low step-ups) accentuates the eccentric forces without having to resort to riskier tactics. This makes LCs ideal as a prerequisite for external loading and withstanding landing forces, cutting forces, and impact forces.2

Vern Gambetta warns that this fast-eccentric work may result in extreme soreness; although not the goal, soreness will give the athlete and coach feedback that the proper exercise tempo was executed.1 I’ll add that coaches can use this to drive buy-in in this ever-growing age of those who equate the value of the work with how bad their body feels afterward. Many young athletes (especially endurance-based) are about “feeling it,” and I can say from experience that they surely will!

Even without the use of external load, intensity is raised by the consistent exposure to rep pace and the gradual accumulation of work density via the dwindling rest periods. In my experience, this is what makes the Gambetta leg circuits a tremendous tool to raise several critical general qualities at once without having to get too fancy.

The beauty of the leg circuits lies in the versatility of the concept. As much as the mini, to half, to full leg circuits are progressions, they can also flow the other way when employing more advanced means or when having to scale them back a bit during a peak or taper phase. We will also find that the ability to stretch, condense, and vary training cycles (based on these circuits) can help coaches scale their plans to fit training age, needs, and time of season.

LDISO Leg Circuit

One variation I discovered is marrying long-duration isometric holds into the circuit at the onset of a beginner’s program. Readers of this website should be familiar with the benefits of LDISOs, and I won’t go into all of them here, but I will add that their placement in this variation serves as a building block for brain and body. Physiologically, LDISOs are paramount for building the musculo-tendon, musculo-fascia, and neuromuscular structures. Targeted long duration isometrics re-educate the tissues to target optimal fascial lines to establish neural networks. The LDISO attacks the origin and insertion points in the extreme lengthened position. The thickening of these points increases the durability and elastic response.3

Psychologically, this increased exposure to time (in the “weakest” joint position) builds a tolerance for discomfort and “slows” things down enough for the athlete to garner familiarity with proper position and posture. In turn, coaches can teach in “live time,” cueing and correcting the athlete’s technique as well as encouraging their effort in the struggle to hold. As most of us intuitively know, tolerance to pain is as much mental as it is physical, and it is a bit of a lost skill in most of today’s athletes.

In the LDISO variation of the leg circuit, the squat, lunge, and jump squat with body weight begin with an isometric hold that precedes five repetitions (the lunges serve as two exercises to train each leg). The first session is comprised of 15-second holds, followed by five repetitions of each respective exercise. We add five seconds to each hold every session, culminating with 30-second holds. Volume is not waved over the four sessions, as we are in an introductory phase and will remain at three sets of each circuit per session.

I discovered the value of marrying LDISOs to the leg circuit while training an athlete via Zoom—the LDISOs allowed them to get a feel for the proper position via physiological signals. Share on XBelieve it or not, I discovered the value of marrying LDISOs to the leg circuit while training an athlete via Zoom this past spring. The lack of physical presence, as well as my normal equipment, called for some critical thinking skills to figure out a way to teach without being there. In my experience, the LDISOs allowed this athlete to get a feel for the proper position via physiological signals.

The Broken Leg Circuit: Put It on the Clock!

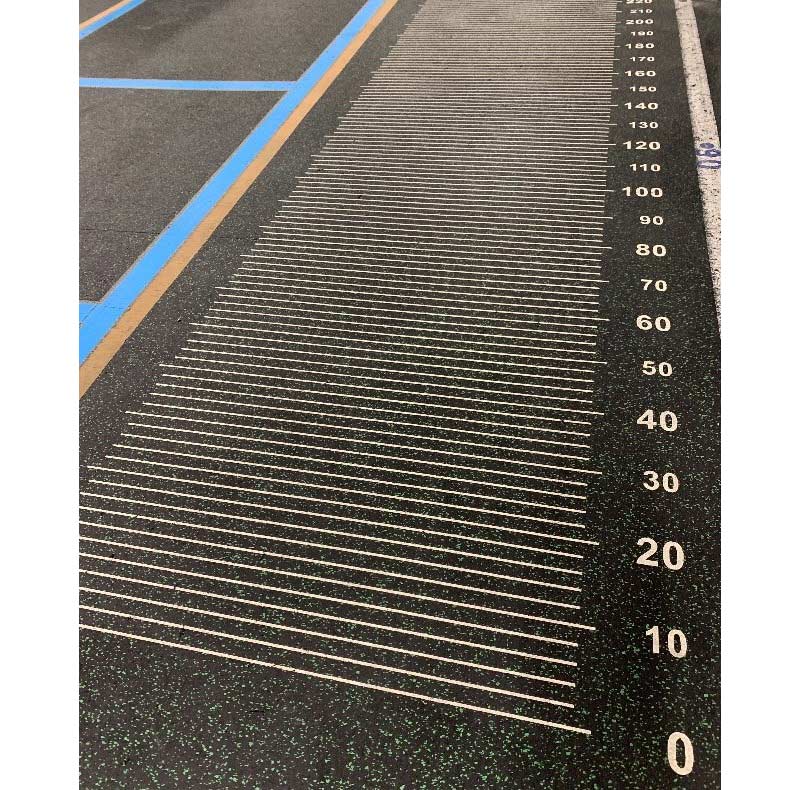

The next step in my progression resembles the order of the standard leg circuit, with a few new caveats. We keep the squat as the first exercise, followed by alternating leg forward lunges, then we introduce the dynamic low step-up, and finish with squat jumps. Accompanying the slight change in exercises is the introduction of the “broken” format, where each exercise is performed on a certain clock interval, as opposed to continuously. (I’m borrowing the term “broken” from the swim world, which denotes breaking up a specified distance with short periods of rest. It is used to train distances in more intense chunks usually above a race pace.)

The clock does a couple of things for us here:

- Athletes can keep an eye on the clock to gauge rep pace. In the first phase, the fatigue from the ISO hold may inhibit the speed of the rep pace, which is okay in my book at that stage because our focus is technique and tolerance. Now, we can give them a goal of rep pace.

- The clock keeps our rest periods honest. The preference here is an EMOM interval, where each exercise is done on subsequent minutes. If we keep the rep goal of one per second on squats and one per 1.5 seconds in lunges and step-ups, then we get a work ratio of 10-20 seconds for the half leg circuit and 20-30 seconds if we use the full leg circuit.

This format allows us to train the aerobic and lactic zones for a prolonged period, as the work-to-rest intervals lie in the 1:2 and 1:1 ratio for the half and full leg circuit variations.4

In broken leg circuits, we do not take an extended rest period; rather, we stay on the interval until the prescribed number of sets is complete. The micro progression (session-to-session) follows Gambetta’s volume prescription, adding a set of work each week. In session 1, the three circuits are done within a 12-minute time, then four circuits in 16 minutes, culminating with five circuits in 20 minutes in the third session (for the sake of milking the slow cooker, we apply a fourth session at week 1 volume).

The macro progression (every four sessions) follows the short-long spectrum, leading off with the half leg circuit for four sessions before applying the full leg circuit for the next four sessions. A cyclic progression will look like this:

- Sessions 1-4: Broken half leg circuit with body weight

- Sessions 5-8: Broken full leg circuit with body weight

From here, I’ve found two places we can go:

- We can add 15-25% bodyweight load and repeat the format. Loading options include dumbbells, sandbags, or weight vests. I’ve found this helpful for athletes who need a bit more strength or need to preserve power.

- We can condense the interval to bridge the gap to continuous leg circuit. I prefer the E45O45 (every 45 on the 45) as this seems to fit a 1:1/2 work-to-rest ratio that will allow athletes a lead-up to the pace of the unbroken circuit.

The amount of time you have with your athletes and the time of season will determine the frequency of the sessions. A compressed progression calls for biweekly leg circuit days, which will get you through each cycle (phase) in two weeks. If you decide to apply the broken EMOM, broken E45O45, to “unbroken” (short-long) progression, you will complete the three levels in six weeks as long as you adhere to the technical execution.

For athletes who have a short time to prepare for practice and play, this compressed model serves as a great general lead-up into competitive season. For the beginning athlete, the compressed model will quickly develop work capacity adaptations and faster learning via frequent practice.

Putting the leg circuits on the clock allows coaches to scale the stress based on needs while checking off many boxes on the GPP list in a fraction of the time. Share on XCoaches can also stretch this on a weekly basis, doubling the time to complete each cycle. This situation would be ideal in longer preparation periods or an in-season model. Putting the leg circuits on the clock allows coaches to scale the stress based on needs while checking off many boxes on the GPP list in a fraction of the time.

The Rapid-Fire Leg Circuit

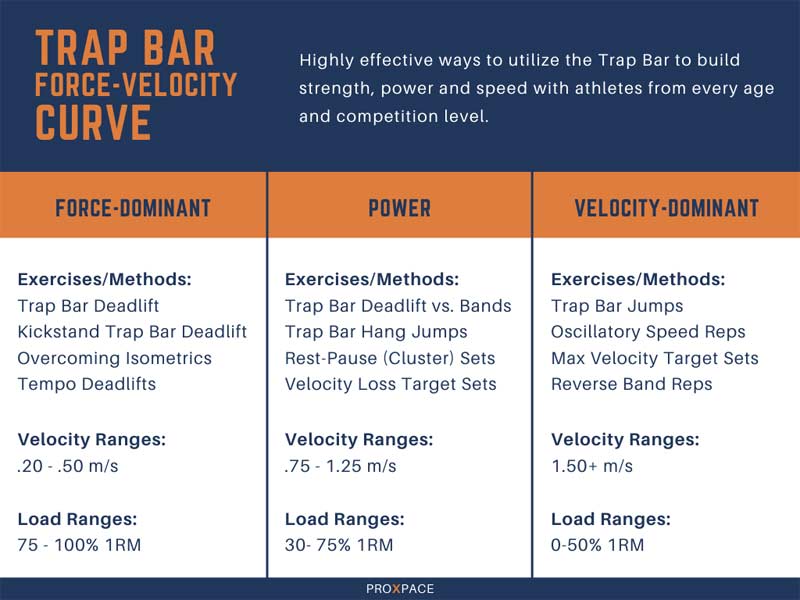

Another variation—based off of Gambetta’s mini leg circuit—that I’ve applied with power or explosive development in mind is what I call the “rapid-fire leg circuit.” Three derivatives of this variation that cover the force-velocity spectrum have evolved for us over the years and have served us best with athletes nearing peak competition or entering a camp. The force emphasis variation is hallmarked by heavier loads in the squat and lunge and intensive efforts for the jumps—this influences the exercise selection for appropriate loading. The idea here is to produce high outputs for repeated efforts along a spectrum of high-force muscle contractions.

The heavier loads in the squat and lunges potentiate the output of the jumps by priming local muscular activity as well as the CNS globally without a high level of fatigue.5 The versatility of this variant allows coaches to adjust exercise selection based on which end of the force-velocity spectrum they are working.

The force emphasis rapid-fire leg circuit is executed using concentric-based movements to emphasize “force-based” output. For the squat exercise, I prefer the bottom-up squat (squat from pins) with the barbell. I keep depth at half or quarter depth to further draw adaptations of higher transfer. Some coaches may argue that the experience and skill level of the athlete need to be high enough to handle a barbell, and I don’t disagree. Movement precision under load is a must so that athletes maintain technique and posture as fatigue mounts, especially in this format.

This where I believe the bottom-up squat can serve as a self-regulator of sorts. Each rep commences from the weakest position of leverage from a dead stop position. Not only does this enable maximal concentric output, but (as practical experience has shown me) it allows athletes to squat correctly without the fear of missing. In other words, if they miss the lift, it won’t budge; the goal is simple—“Push!” For those coaches who use percentages of 1RM, 70-80% for the squat works well.

The lunges call for the classical forward lunge technique:

- Project the hips forward with the back leg.

- Reverse your forward momentum with your front leg.

- Explode back to standing position.

If using a barbell, 50-60% (of squat max) for the lunges is more than enough. And again, we can add “transfer” here in the form of horizontal force by selecting cord lunges, per Dr. Yessis. In this case, you would use a cord that slows you down a bit, minimizing displacement of the body after the rep.

In keeping with our force priority, the dynamic step-ups and squat jumps can be done with external load in the form of a weight vest or sandbag for the step-ups and a kettlebell for the jumps at about 15-25% body weight. By nature, the dynamic step-ups begin with the jump leg in the position of weakest leverage, so we do not have to make any tweaks here. The preferred jump squat calls for the non-countermovement version where the kettlebell (or weight) will start from the floor. The athlete can jump onto a box of moderate height or keep it floor level. The Just Jump mat is a great tool to keep intent honest, as the visual result of their efforts will show them the story.

You can also adjust the format of this variation to fit preservation of higher quality of output or the ability to repeat it. Our rep template is based off of four squats, two lunges each leg, two dynamic step-ups each leg, and two squat jumps (14 reps total). If we train for increasing output, then we simply go through the circuit continuously and rest at least double the time it took to complete. If this is the case, then using the jump height to manage overall volume may be a wise application so as not to tip the CNS bucket too far over, especially during periods of quality retention or in-season. We typically cap the number of sets to five or cease sets if an athlete cannot maintain 90% of their best jump. The intent is to hit personal bests on a session-to-session basis while preserving that higher end quality.

For specific work capacity development, we repeat this sequence continuously three times and time the duration of the set. Rest runs about half of the running time before repeating. You can certainly track jump height here, but accepting a larger drop-off (80% of best) will help your athletes reach the volume necessary to develop the repeat quality.

In this variation we attempt to wave volume by adding a set of work each session. In week 1, the groundwork is laid with three rounds of the circuit done at a 1:1/2 work-to-rest ratio (126 total reps). The next session we aim for an extra round through as long as the athlete can maintain that 80% of jump height, and on week 3, we’ll attempt to culminate the cycle with five sets (168 and 210 reps, respectively). If we have more time, we’ll give a six-session limit here for athletes to earn the five sets or just simply see what we can do in three sessions. (The 80% marker is akin to the 20% bar speed drop-off that was found to better increase vertical jump height and overall growth of the type II explosive muscle fibers discovered by Dr. Mann.)

Video 1. Featured here is a lite version of the above, used with younger athletes who don’t have a large experience with higher force movements, but you can get the idea.

If we really want to prime the system for higher outputs with higher intensity via speed, then we can break this down a little further. In this Cal Dietz-inspired variation, we ratchet the exercise selection to the velocity end with loaded jump squats (at half or quarter depth), split jumps, dynamic step-ups (low box), and the countermovement jump. (For more qualified athletes, you can substitute the lightened split jump and the depth jump for the CMJ.)

The reps go down to a scheme of two, one each, one each, two, and repeat this sequence 3-5 times (24-40 reps), à la the potentiation clusters seen in the triphasic high-speed methods. The rest between rounds should be double the duration of the set or more, to allow for adequate rest so that outputs can increase each set or be preserved, at the very least. The high-quality emphasis dictates a volume limit, so we do not add a set per session but rather aim at setting bests in jump height (or at least preserve our day’s best).

Video 2. Creating higher intensity via speed in the “rapid-fire leg circuit.”

The genius of Gambetta’s leg circuits is that they allow for bilateral and unilateral lower body training across a variety of muscular contractions. Adding elements such as long-duration ISOs, interval based, and adjusting the exercise selection can give coaches viable options along the general-specific spectrum. The marriage with LDISOs adds benefits to developing the aerobic base, as well as technical learning.

The genius of Gambetta’s leg circuits is that they allow for bilateral and unilateral lower body training across a variety of muscular contractions. Share on XBridging this gap by putting the base movements “on the clock” gives athletes a progressive segue to the “right of passage” earned in the continuous circuits. The rapid-fire variations offer a more specific training option for explosive leg development that coaches can adjust along the force-velocity spectrum to meet needs.

Some of the greatest coaches in history have a simple catalog of “plays,” but myriad effective variations of them. For those with leg circuits in your catalog, I hope this writing adds variations to your creative arsenals.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Gambetta, V. “The Gambetta leg circuit.” HMMR Media. 12/18/10.

2. “Legs, legs, legs.” GAINcast Podcast #187. 4/27/20.

3. Fox, E.L. and Mathews, D.K. Interval Training: Conditioning for Sports and General Fitness. W.B. Saunders Co., 1974. pp 40.

4. Demayo, J. The Manual Vol. 3. Central Virginia Sport Performance, 2018. pp 138-139.

5. Schmarzo, M. and Van Dyke, M. Applied Principles of Optimal Power Development. E-book, 2018. pp 17.