A pervasive narrative runs through the discussion around training for the sport of surfing—circulated both by coaches of elite surfers and surf websites appealing to recreational surfers—which is to only use surfing to get better at surfing. This does not help surfers, as many surf sessions can in fact be unremarkable. Dictated by fickle swells, tides, and wind, the sport itself isn’t always the best stimulus for physical development.

Yoga and bodyweight-only training are other infatuations in the surf community, with many convinced that these methods alone can keep them aligned, believing you only carry your body weight when you surf, so that is how you must prepare. This camp seems to underestimate the sheer force and power of the ocean.

Finally, there are the Indo Board and balance ball fanatics, who are convinced that the sensorimotor demands of balancing on a plank or ball replicate an ocean because they share an uncanny visual resemblance.

My fellow surfers may be quick to label me as well when they know I work as an S&C coach for a rugby team: in the meathead camp? What you must understand is that I am not in denial about the potential benefit of the above elements for training in a surfer’s program. Instead, I am disillusioned by the narrative of being married to one approach at the expense of all others. Monogamy does not apply to training methods.

I am disillusioned by the narrative of being married to one approach at the expense of all others. Monogamy does not apply to training methods. Share on XAdditionally, I am curious and observant. As a coach, I am constantly challenged to find evidence-based ways of improving performance. As a surfer, I still see surfing’s resistance to effective preparation lingering at all levels of the sport, despite its inclusion in next year’s Olympic Games.

It may be that people in the sport are just trying to keep it soulful and carefree, while sticking their fingers up at the jocks (an integral part of its culture). I love it and salute it. As coaches, however, we need to show that we’re not here to wring the fun from the pursuit:

- If you find yourself getting better at something, does this give you a sense of fulfillment?

- If you love something and you’re forced out of it with an injury, do you feel less fulfilled?

- If you know you’re preparing effectively for something, do you not feel more confident in your abilities?

These key questions provide the catalyst for surfers to understand that training for their sport aims to provide more fun, for the competitive and recreational surfer alike. With this in mind, and with the hope of slowly chipping away at the current narrative, I’ll provide training tips for surf athletes from the evidence base. I believe much of the content I will cover in this article would also be applicable (with some tweaks) to other board sports (skateboarding, snowboarding, and paddleboarding, etc.). Today, we kick off with dryland strength and power training tips and what I see as six essential exercises.

Warning! Before delivering any of this content to a surfer, you may have to counsel them through their unease.

Luckily, I’ve created a quick cheat sheet of replies:

- “You won’t get big and bulky, unless your diet is out of control and you’re taking special ‘vitamins’.”

- “You won’t become as stiff as your board if you train through a full range of motion.”

- “World Surf League (WSL) surfers aren’t the only ones who are allowed to train for their sport.”

- “If there’s waves, get in the bloody surf.”

For Paddling

(Photo courtesy of Sebastian Potthoff.)

What’s Happening Here?

Believe it or not, 44-54% of the time in a surf session is spent paddling.1 Paddling into the lineup. Paddling across to the peak. Sprint paddling into waves. Paddling happens a lot.

Faster. Move faster. C’mon, for #$@&% sake! These are the thoughts that rush forward when a big set rolls through and a surfer gets “caught inside” and is paddling for safety. And then, reaching the lineup after having had to bail their board as the wave dumped its payload on their head, there is relief mixed with annoyance that “just two strokes more and I would’ve made it over the back of that one.”

Faster paddling has been found to be a determining factor between different levels of surfers…thus, paddling is perhaps the most important quality to improve through training. Share on XFaster paddling may not only spare the anguish of getting caught inside; it has been found that it is also a determining factor between different levels of surfers.2 In WSL competitions, surfers with a higher sprint paddling speed achieved better competition results. Those surfers with a sprint paddle of <1.7 meters per second tended to be eliminated before round 5, compared to those who had a sprint paddle of >1.9 meters per second, who reached the quarters at least and could go on to win the final.2

Higher sprint paddling allows competitive surfers to paddle into steeper waves with a faster entry momentum into those waves, increasing the number of maneuvers and therefore enhancing fun and/or scoring potential.3 Thus, paddling is perhaps the most important quality to improve through training.

How Do We Improve It?

Paddling will increase paddling ability. But increasing strength will also massively improve this skill. In paddling, you anchor your arm in the water and “pull” and then “push” your body across the surface. There is no contest as to which are the best exercises for improving this action: pull-ups and dips are the most integral movements that mimic this movement pattern and activate the correct musculature.4

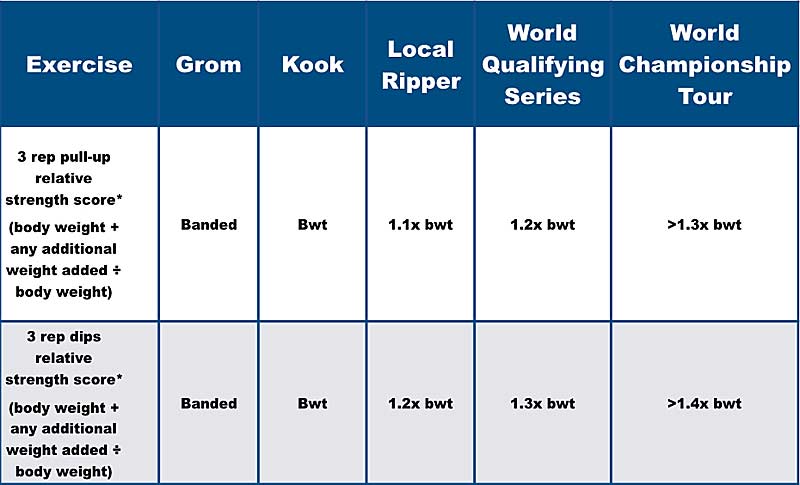

These two relatively simple exercises should of course be trained through a full and comfortable ROM. Surfers new to strength work may need assistance through the use of banded pull-ups from higher to lower elasticity. For those better versed in training, bodyweight reps and then additional plates added through the use of a weight belt should be the goal.

Standards of upper body strength that can be targeted are outlined below. Some of the world’s best male surfers can have a pull-up of 1.4 times their body weight. For an 80-kilogram surfer, that would mean 35 kilograms extra weight added for a total weight of 115 kilograms. This is not a huge pull-up relative to other sports, but highly sufficient for the demands of surfing. However, even a progression from doing three reps with a band to three reps at body weight should give appreciable improvements in paddling ability.

For Turns, Snaps, and Carves

(Photo courtesy of Sebastian Potthoff.)

What’s Happening Here?

Turns, snaps, carves, or cutbacks all look and feel best when there’s spray fired all over the lineup. Achieving maximum spray in these maneuvers requires adequate lower body strength and power to displace as much water as possible through the application of force through their legs and onto their board.5

If a surfer can apply more force, or apply it more quickly to exhibit this, competitive judges have the potential to score maneuvers more highly. For recreational surfers, those paddling back out into the lineup will be thinking Jesus’ juice is falling on them. They will not fathom that, in fact, it’s just them hitting the lip.

How Do We Improve It?

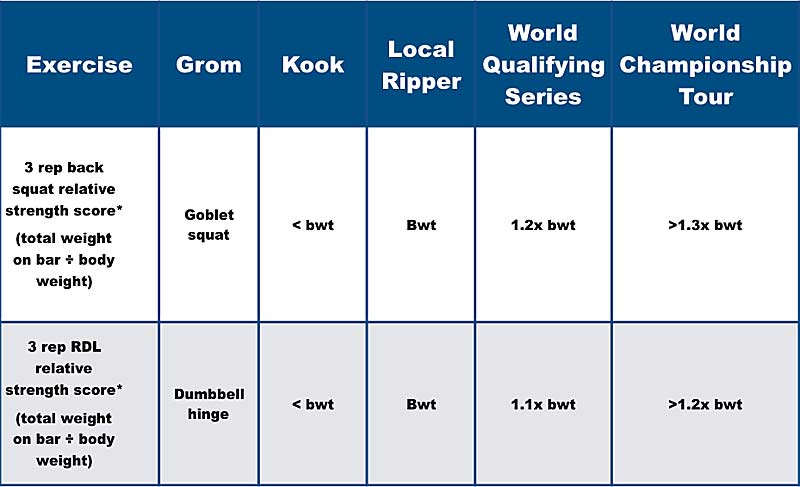

Talent, technique, and timing clearly have significant parts to play for flowing yet powerful turns, but a surfer having adequate levels of lower body strength will go a long way toward better displaying these skills. In these maneuvers, the surfer compresses and loads up their legs before extending their hips at just the right moment. The best exercises for improving these actions would be two bread-and-butter strength movements: barbell back squats and Romanian deadlifts (RDLs). They are often done, and rightfully so, because there are few better movements to load the ankles, knees, hips, and the powerful musculature of the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes.

Talent, technique, and timing clearly have significant parts to play for flowing yet powerful turns, but a surfer with adequate levels of lower body strength will better display these skills. Share on XLike any athlete, but particularly surfers who may have never entered a gym, it is imperative that they master technique before piling on load in these two exercises. My cues for the squat: With a just-outside shoulder-width stance, sit down as far as is comfortable in between your hips. Think about pushing your knees out slightly as you go down to activate your glutes and push through your quads on the ascent.

For the RDL: Pick up a bar with a just-outside shoulder-width grip and pull the shoulder blades back and together as if you were trying to crack a nut between them. Unlock the knees and push your rear-end back as far as you can (like the Insta models do) while dragging the bar down the thighs to mid-shin before coming back up again. For both movements, keep a controlled tempo on the descent of about two seconds (loading up) and fire back up as fast as possible with control (extend) on the ascent, just like a turn.

Those new to strength training can perform a standard progression of goblet squats and dumbbell hinges before moving on to using the barbell. Lower body strength standards are outlined below.

For Aerials and Floaters

(Photo courtesy of Sebastian Potthoff.)

What’s Happening Here?

Airs and big floaters are obviously advanced moves incorporating a multitude of complex skills, but the evolution of the sport has entered the territory of skateboarding and snowboarding and is set to stay there. Shouldn’t every surfer prepare for the day that they begin to dabble in these dark arts? For the day that they get 0.1 seconds of air that does not include falling off the back of a wave?

Essentially, airs can be broken into three phases: takeoff, flight, and landing. The take-off and landing phases of airs and the landing phase of floaters are the ones we can most affect with physical training, as that is when the body meets the most impact.

How Do We Improve It?

This “impact” I am talking about is clear: stomping airs and floaters provide the greatest potential risk for injury of any maneuver6 (two-time world champion John John Florence’s ACL injury is just a recent example), particularly if surfers don’t possess adequate lower body strength and power. While landing one of these maneuvers, surfers commonly absorb forces of up to 4-6 times their own body weight through their ankles, knees, and hips.7 Having well-developed strength and power will also enable surfers to launch themselves higher off the lip of the wave, getting some of that sweet, sweet hang time.1

You have to be strong and powerful to get a heavy bar off the floor quickly with good technique or to come up with a heavy weight on your back. Therefore, the squats and RDLs above will allow surfers to absorb this weight, just like air and floater landings. But to go one step further, we must also replicate the movement pattern of these complex movements and their landings on land to develop injury robustness through proper joint alignment.

Video 1. Drop & Stick, Jump & Stick, and Rebound & Stick.

A box or step that is around knee height (~50 centimeters) is required. The progressions start with a basic drop and stick (D&S), replacing the drop with a jump (J&S) and then finally onto a rebound and stick (R&S). For all of these, “sticking” the landing in a surf stance/quarter squat position without excessive knee valgus is desired (there will be some knee valgus in the back leg, as this position is essential in the sport). The aim of the landings here should be to land softly, as if you didn’t want to wake up someone sleeping in the next room, which is especially hard after a chaotic rotation. This will teach absorbing the force of landings and better coordination of the body in space when in the ocean.

To help in applying that force off the lip in the take-off phase of airs and getting some tasty height, jump training replicates these movements and will be highly effective in improving them due to the development of vertical power through the lower body.

Video 2. CMJ, rotational CMJ, and loaded CMJ.

The key exercise here is progressing a basic countermovement jump (CMJ): In your squat stance, in one flowing movement, go down to a comfortable depth (~quarter squat depth) and jump as high as possible to the ceiling. No need to bring the knees up, but aim to get hips as high off the ground as possible. Land as described above. Progressions (below) aim to add complexity through surf-specific rotations before finally adding load in the barbell CMJ.

Strength and Power Work Can Be a Lucrative Performance Enhancer

(Photo courtesy of Sebastian Potthoff.)

Just like yoga, bodyweight, and balance board training, strength and power work is only one small element of the performance model to improve surfing performance. However, it is especially important to adopt due to the current narrative within surfing culture that steers most surfers hastily away from anything gym-based. The six exercises above—coupled with finishers of supplementary work for torso/core strength and power, ankle and hip mobility and rotator cuff robustness—will provide a great foundation for the training of surfers.

Considering surfers’ low training ages, increases in whole body strength & power through these generic exercises may be particularly beneficial for performance enhancement. Share on XFurthermore, considering surfers’ low training ages, increases in whole body strength and power through these generic exercises may be particularly lucrative in terms of their potential for performance enhancement.

Join me soon for another part in this series, which will take a look at energy system development for surfing.

All photos courtesy of Sebastian Potthoff, Instagram: @saltwatershots

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Tran, T.T., Lundgren, L., Second, J.L., et al. “Comparison of Physical Capacities Between Non-Selected and Selected Elite Male Competitive Surfers for the National Junior Team.” International Journal of Sports Physiology & Performance. 2014.

2. Sheppard, J. “Masters & servants: How the preparation framework serves the performance model.” UKSCA Conference Presentation. 2017.

3. Farley, O., Harris, N.K., and Kilding, A. “Physiological Demands of Competitive Surfing.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2011;

4. Coyne, J., Tran, T.T., Secomb, J.L., et al. “Maximal Strength Training Improves Surfboard Sprint & Endurance Paddling Performance in Competitive & Recreational Surfers.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2016.

5. Secomb, J.L., Farley, O.R.L., Lundgren, L.E., et al. “Associations between the Performance of Scoring Manoeuvres and Lower-Body Strength and Power in Elite Surfers.” International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching. 2015.

6. McArthur, K., Jorgensen, D., Climstein, M., and Furness, J. “Epidemiology of Acute Injuries in Surfing: Type, Location, Mechanism, Severity, and Incidence: A Systematic Review.” Sports (Basel). 2020;8(2):25.

7. Lundgren L.E., Tran, T.T., Nimphius, S., et al. “Comparison of impact forces, accelerations and ankle range of motion in surfing-related landing tasks.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2016;34(11):1051-1057.