Coach Tony Villani is a sports performance coach and Founder of his business XPE Sports Performance and Fitness based out of Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Tony specializes in movement sports training.

Tony has trained many NFL players, including Jamal Lewis, Cris Carter, Anquan Boldin, Mark Ingram, and Kareem Jackson.

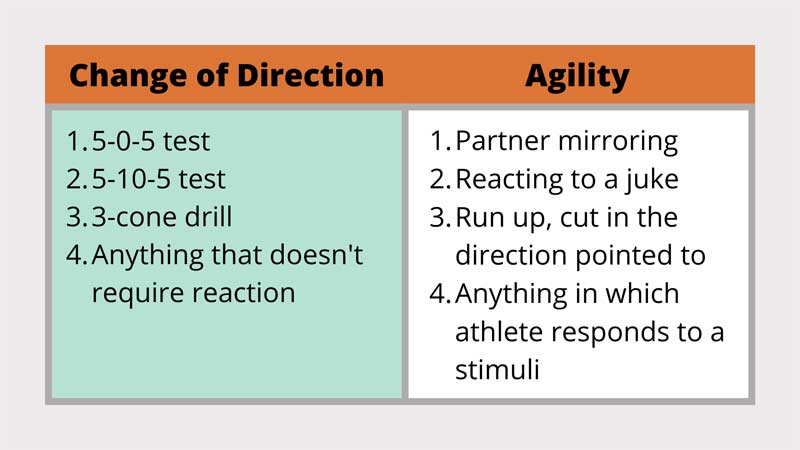

Coach Villani explains why game speed is not the same as top speed, and that we should consider the time we allocate toward training specific qualities that translate to game day performance.

Connect with Tony and Cody:

Tony’s Media

Twitter: @XPE_Sports

Instagram: @XPESports

Cody’s Media:

Twitter/Instagram: @clh_strength

Website: www.clhstrength.com

YouTube: Cody Hughes

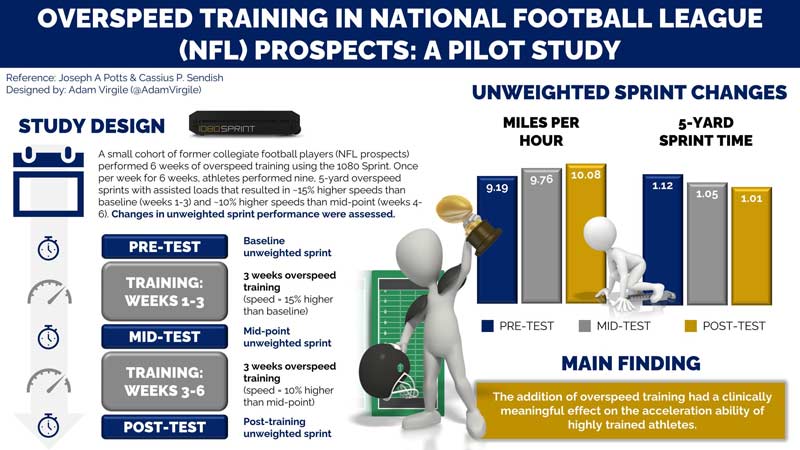

Cassius Sendish is the Assistant Director of Sports Performance and Combine Coordinator at TopSpeed. He returned to TopSpeed in a coaching capacity, earning his performance specialist certification with EXOS, after spending the previous three years coaching football at the University of Kansas.

Cassius Sendish is the Assistant Director of Sports Performance and Combine Coordinator at TopSpeed. He returned to TopSpeed in a coaching capacity, earning his performance specialist certification with EXOS, after spending the previous three years coaching football at the University of Kansas.