By Matt McInnes Watson and Ash Buckman

Plyometrics are a powerful training method used by many athletes within speed and power sports. The effectiveness of the training can transform an athlete’s ability to utilize and produce force quickly, with greater precision and locomotive control. The development of plyometrics as a training tool and its link with sport-specific expression of movement has grown in recent years and led to an increased use of plyometric exercises. The variations of plyometric movements range from highly dynamic, intense movements in a linear fashion to a large array of extensive landings and takeoffs in multiple directions and planes.

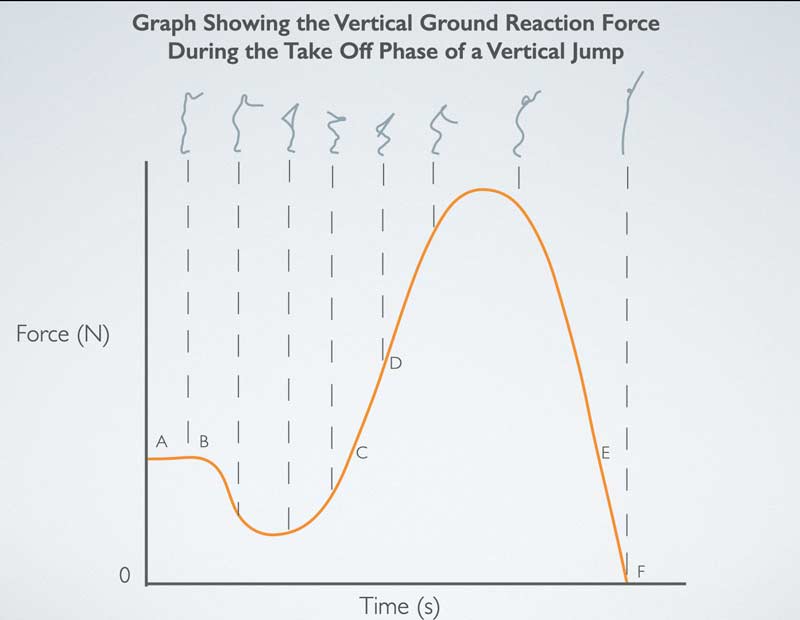

Despite the growth of the training method, the testing of plyometrics has been limited to vertical, angular, momentum-based (on the spot, up and down) movements. This type of movement enables us to determine simple measurements of ground contact time (GCT) and jump height/flight time (JH/FT) to calculate metrics like the reactive strength index (RSI). Although this may be deemed an effective way to measure forms of reactive strength and plyometric potency, it does not have the capacity to measure influences of horizontal-based momentum.

Although RSI may be deemed an effective way to measure forms of reactive strength and plyometric potency, it does not have the capacity to measure the influences of horizontal-based momentum. Share on XMeasuring jump height and/or the incoming momentum of a movement that possesses more of a horizontal focus (e.g., bounding) is difficult using force plate, camera, and VBT technologies. The influences on landings—such as incoming descent angle and velocity—can often produce data that is difficult for coaches to understand and use as part of their movement assessments. The sport science and coaching community understands the specificity of more horizontally focused plyometrics and their link to sporting movement—therefore, the need for a new testing and monitoring metric is critical!

Outputs and Momentum

As previously mentioned, RSI is a widely credited testing metric for providing simple output data to assess an athlete’s reactive strength. That being said, the data that is recorded may be deemed symptomatic, showing the outcome of a movement. Yet understanding the reasoning behind outcome variables can be more important and can often provide greater clarity on the athlete’s performance. In plyometric movements with varying approaches, we can identify differences in outcome performance through comparison of the incoming momentum of the previous movement.

When it comes to truly understanding what is happening at a given moment within sport or training, we must analyze influencing factors to determine the reasoning of the outcome. This can follow a process similar to a physical therapist taking medical assessments, looking at what contributed to the injury, and linking this to the symptoms. If we’re being overly critical of the output measures, we are only getting half the story, and it can become difficult for coaches to truly understand how to further change and impact these output metrics and athlete performance.

So how can different incoming momentums change the outcomes of a takeoff?

We need to consider the loading pattern and what influences that loading pattern:

- Did the athlete fall vertically?

- Did the athlete fall horizontally?

- Was the incoming momentum affected by a greater entrance velocity?

- Is that landing affected by a higher velocity produced by an increase in negative foot speed?

When you consider these questions, you can start to understand how just considering output metrics in dynamic movement is half the story. Another important consideration when asking those four questions is: what are the output metrics telling us?

There are three potential outcomes:

- The athlete is gaining momentum.

- The athlete is losing momentum.

- The athlete is maintaining momentum. (Although this may be deemed as important, the likelihood of exact momentum maintenance is very low, and each landing to takeoff varies slightly.)

If we bring these influencing factors together with the potential outcomes, we often see these typical occurrences:

- Too fast incoming momentum = losing momentum (often seen in the triple jump).

- Too long falling momentum = losing momentum (often seen with depth jumps).

- Smaller incoming momentum = gaining momentum (often seen in acceleration-based practices).

When looking back at the first two examples here where the athlete is likely to lose momentum, be it speed and/or jump distance, we as coaches must assess how these influencing factors that may negatively affect performance can eventually be used advantageously for the athlete.

We need to understand how to assess our athletes’ movements & use a new form of plyometric testing to help positively impact their output capacities when dealing w/greater incoming momentums. Share on XThe reasons for declines in momentum in these instances are that the athlete cannot handle the eccentric forces upon landing and/or the rate in which the eccentric portion of the landing is loaded. It’s therefore our mission as coaches to understand how we can assess our athletes’ movements and use a new form of plyometric testing to help positively impact their output capacities when dealing with greater incoming momentums. By just assessing output metrics, it becomes difficult to disseminate this data into our coaching and identify ways in which we can affect technique and task to improve performance.

Video 1. Bounding exercise with flight times and RSR calculated.

The Reactive Strength Ratio (RSR)

The RSR is a measurement of both the incoming and outgoing momentum of a plyometric landing and its influence on the ground contact.

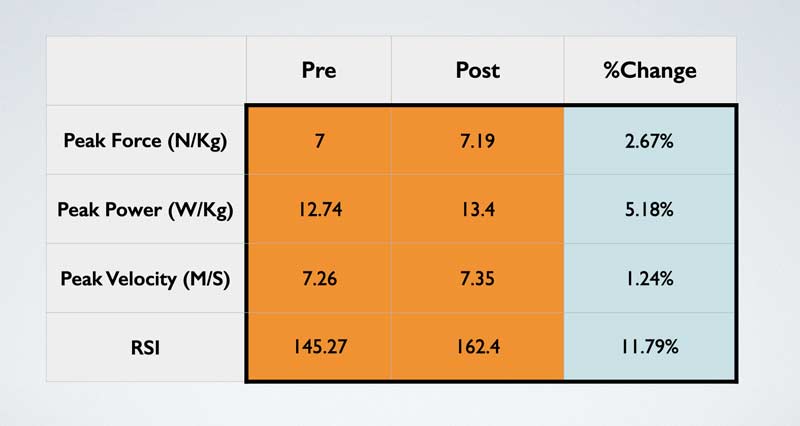

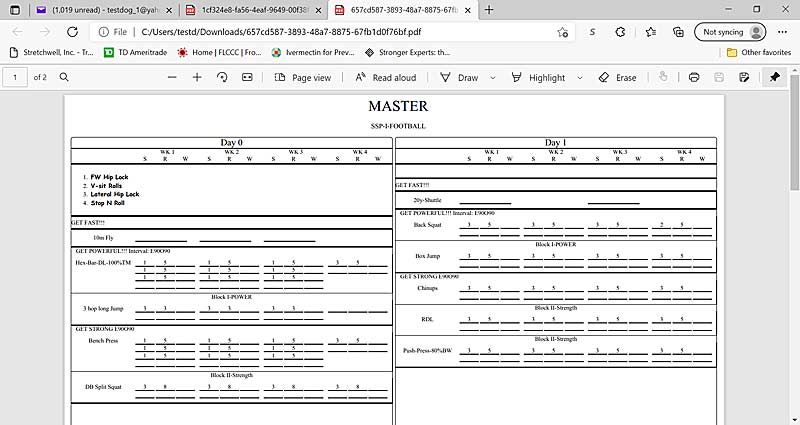

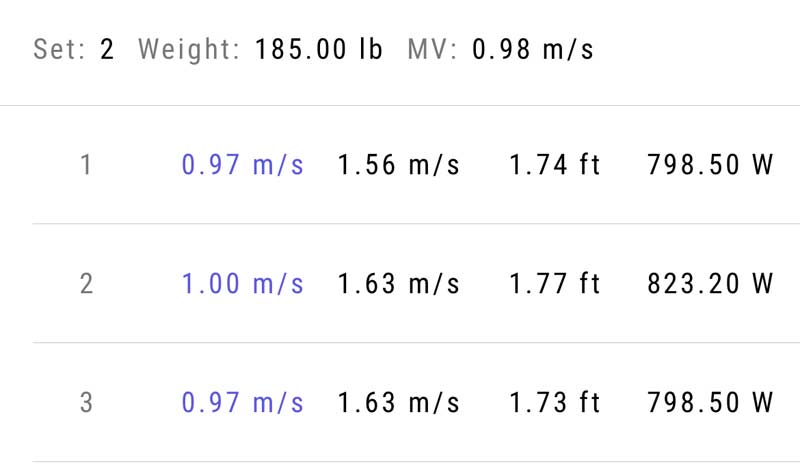

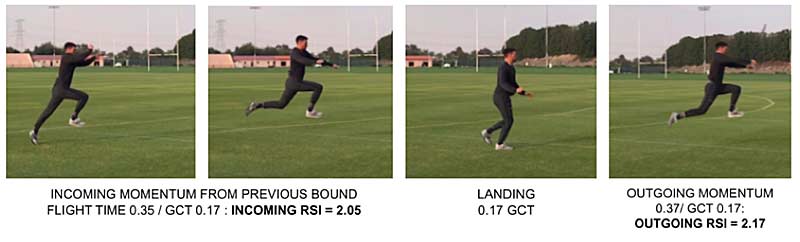

When looking to calculate RSR, the FT before and after a landing should be measured while monitoring GCT. By accounting for both FTs, the incoming approach can be used to assess its influence on GCT, outgoing FT, and the performance outcome (RSI). Both FTs are individually divided by the GCT, giving two initial RSI scores. The outgoing RSI is then divided by the incoming RSI to give a ratio of 1 based on the impact of incoming versus outgoing capacities.

-

RSR = (Outgoing RSI)/(Incoming RSI)

Incoming RSI: Flight time – 0.35/0.17 GCT = 2.05

Outgoing RSI: Flight time – 0.37/0.17 GCT = 2.17

RSR: 2.17/2.05 = 1.059

Understanding the Ratio

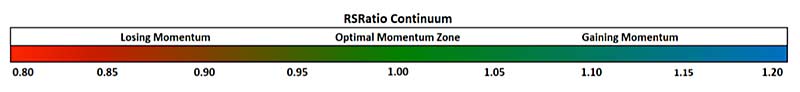

When delving into the data, it’s important to understand the ratio and what it tells us. A perfect ratio of 1 relates back to the maintenance of momentum, which could be classed as a state of equilibrium. We can then base all other movements, whether they’re <1 or >1, and account for them having either lost momentum or gained momentum.

Ratios greater than 1 (>1) suggest that the incoming flight time is managed well upon eccentric loading for the athlete and they’re able to handle the force to propel themselves out of the takeoff, creating a larger outgoing flight time (increasing momentum).

Ratios lower than 1 (<1) suggest a greater incoming flight time (e.g., a high platform depth jump) that the athlete struggles to couple the energy of to create an equal or larger outgoing flight time (losing momentum).

Due to the previously mentioned difficulties of achieving a perfect ratio of 1, bandwidths are used to gain a greater perspective of the athlete’s ability to utilize or not utilize incoming momentum. The initial bandwidths are set within the 10 percentiles of the ratio of 1 to provide coaches and athletes with a guide to get the most out of plyometric adaptations.

The reasoning behind staying within the bandwidths of 0.90 to 1.10 is to ensure that athletes are training within elastic/plyometric zones, whether that’s overloading the athlete by spiking the eccentric GRF or looking to produce a higher output through the concentric takeoff portion of a movement. It’s important to understand that when we step too far outside these bandwidths there becomes a point of diminishing return. Saying that using just movements that possess a ratio of 1 is the way to train for plyometric adaptations would be foolish, and obvious forms of overload (especially through eccentric loading—ratio of 0.90) are critical for developing athletes.

But too often, coaches and athletes bang on the doors of plyometric overload and leave aside critical areas for developing the velocity side of landings. We must understand that high GRF must come with rapid GCTs in order for movements to be reactive, elastic, and, most importantly, efficient.

It must be noted too that the optimal ratio of 1 can be a sign of locomotive rhythm for the athlete in a given exercise. Rhythm can be the foundation of force-velocity acquisition, showing that an athlete’s competencies at a given movement in time are handled with efficient locomotive properties.

Using the Data to Guide the Coaching Process

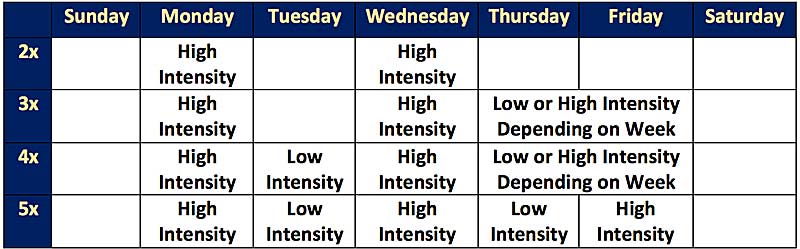

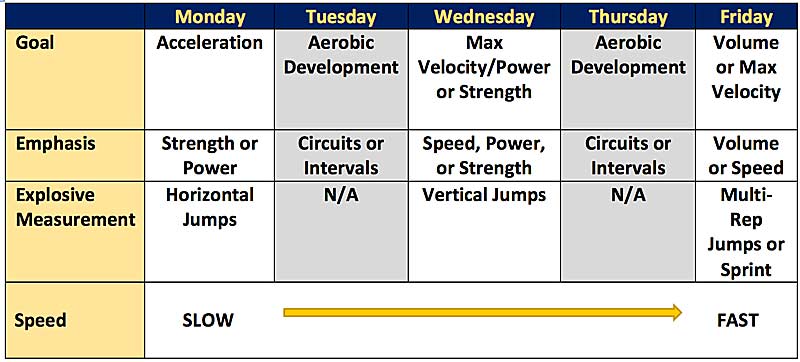

The common practice of dividing plyometrics into intensive and extensive movements has given coaches a simplistic way to program dynamic training. The split is a similar reflection of maximal and submaximal categorization of movement, which also has implications when measuring RSR.

Intensive or maximal plyometrics will be most critical for monitoring RSR bandwidth. Often, the use of maximal intent for a given task shows the true colors of how the body reacts to maximal output stimuli. This may highlight weak links and disconnects of skills that result in biomechanical faults that inherently diminish the performance of said task or movement.

Analysis of the movement using the RSR could be a way of discovering asymmetrical discrepancies or a lack of eccentric loading control of the given movement, says @mcinneswatson. Share on XCoaches can be left second-guessing or unaware that an athlete’s RSI score may be low due to an overwhelmingly low ratio of <0.90 (high eccentric loading). Equally, monitoring of RSR bandwidth can be used to detect if the eccentric loading is placing enough stress on the athletes, with regard to producing ratios >1. This also plays a critical role in monitoring fatigue and potential overuse or stress-based injuries.

Extensive or submaximal plyometrics have a fundamentally different emphasis and intent—loading or output are not always KPIs. Submaximal strategies are implemented for physiological and neuromuscular adaptive reasons, such as:

- Higher landing volume to accommodate tendon CSA growth/stiffness.

- Better timing and efficiency of the SSC.

- Heightened proprioceptive awareness.

- Overall mechanical landing improvement.

As with many submaximal or extensive strategies for training, rhythm becomes the foundation of movement. It is usually the case that submaximal effort can give way to conscious, relaxed states to then place further efforts on smooth locomotion. This is achieved through, ideally, an optimal RSR of 1, when athletes are able to utilize and produce force efficiently. If an athlete is struggling to maintain speed, fluidity, or rhythm during an extensive plyometric activity, then analysis of the movement using the RSR could be a way of discovering asymmetrical discrepancies or a lack of eccentric loading control of the given movement.

Videos 2 & 3. Extensive crossover bounds and extensive split exchange leaps.

Optimal locomotive performance often requires movement in the most intense manner but is also achieved in the smoothest and most efficient way. Often in sport, the fastest and best performers aren’t always producing the highest force but are using it effectively to accomplish the sporting skill best (whether that’s sprinting, pitching a ball, or outmaneuvering a defender).

Therefore, our utmost aim as coaches is to develop movers who execute specifically intense movements like sprinting or bounding for distance with an optimal RSR of 1.

Our utmost aim as coaches is to develop movers who execute specifically intense movements like sprinting or bounding for distance with an optimal RSR of 1, says @mcinneswatson. Share on XFurther Observations and a Sampler of Unilateral Landings

There are two options for unilateral plyometrics:

- Hopping (unipedal—moving on just one leg).

- Bounding (bipedal—alternating legs).

Although both are considered unilateral, they have some inherent differences when it comes to landing forces, mechanics, and neuromuscular stimulus. A consideration and finding from the RSR brings up the asymmetrical differences that may be observed during bounding.

All athletes will possess an asymmetrical balance between legs, with what may be considered a dominant and nondominant leg. Other descriptions may be a “strength leg” and “speed leg” that are based on takeoff preferences in jumping actions.

This difference brings up scenarios during bounding that may sway the use of maximal intent versions. For an athlete with a dominant left leg, when bounding for distance left to right, due to the left leg’s capacity, the flight time of the incoming right leg landing is likely to be high. This subsequently has a knock-on effect due to the nondominant right side then having to deal with the larger incoming flight that will inevitably spike a high eccentric ground reaction force. The right leg’s inferior capacities can potentially have a further effect when coupling energy from what may be deemed a supramaximal landing, which cannot produce an equal outgoing flight time (= RSR <1).

This continues to have a knock-on effect with the lack of influence it may bring when alternating back to the dominant left side as it receives what should be maximal—but is in fact a submaximal—loading of the next landing due to the nondominant leg’s incapacities to utilize and express force. This leads the dominant left to then proceed in having to recreate momentum again (= positive RSR >1).

The scenario can create a vicious cycle where both legs are not training within the zones a coach may wish for, especially if the intent is to work on maximal output. This might be the typical response we may want with plyometrics, by highly loading the eccentric phase, but when using unilateral bipedal movement (bounding), this may bring up some faulty patterns that could lead to potential asymmetrical landing injuries.

It must be noted, too, that a certain level of dominance will always be there for some athletes but must only be present at a minimal level. Negative influences that were previously discussed must be monitored through the ratio to help determine further if gait and loading mechanics are leading to overuse and/or potential injury.

Final Takeaways

The RSR can be a great tool for evaluating and monitoring a particular plyometric or dynamic movement in time. The ratio can provide athletes with a measurement of their capacity to deal with all landing and takeoff scenarios, no matter the trajectory of the incoming movement.

The reactive strength ratio can provide athletes with a measurement of their capacity to deal with all landing and takeoff scenarios, no matter the trajectory of the incoming movement. Share on XWhat’s important about the ratio is that it does not replace RSI but becomes part of the story for movement assessments. Output RSI is always present when measuring RSR, so you still get a value to determine the output capacity of an athlete’s reactive strength. With both load tolerance measured in the ratio and dynamic output from RSI, we can now better understand the reactive abilities of our athletes.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Ash Buckman is a performance coach based in the U.K. who has a master’s degree in sport science. He has worked within many high-performance environments across sports including basketball, track and field, and motorsport. His work includes strength and conditioning and soft tissue therapy, with a strong interest in the use of plyometrics in sports performance.

Ash Buckman is a performance coach based in the U.K. who has a master’s degree in sport science. He has worked within many high-performance environments across sports including basketball, track and field, and motorsport. His work includes strength and conditioning and soft tissue therapy, with a strong interest in the use of plyometrics in sports performance.