As strength and conditioning coaches, we aim to improve the athletic performance of our athletes and strive for a healthy and high performing team. The beauty of this profession is that everyone attempts to reach this goal differently; everyone has their own philosophy, their own mentors, their own biases, their own personal experiences, and their own way of doing it.

No one program is an exact copy of another; even if it starts off that way, it will inevitably change to fit the new training environment, team, culture, and group of athletes.

We take real pride in how our strength and conditioning programs look, what our progressions are, and how our testing numbers have changed. These are all inherently good things—they hold us accountable to our work and can lead to an evaluation of the extent to which we are or are not doing a good job. We should be constantly learning best practices for the training and care of our athletes, have growth rather than fixed mindsets, be curious to learn from all sports and coaches, and always be willing to adapt or change our minds if sufficient evidence causes us to rethink our old methods.

I find it funny, though, how over the past five years of working at Furman, one of the biggest learning curves for me has actually been letting some of my programming go and giving it over to the athletes. Giving them a choice during optional workouts is a no brainer for me now because:

- The buy-in is high

- The intent is high

- The energy is high

- The attendance is high

Giving some of the choices up to the athletes is so effective that, in some cases, the overall training frequency during the summer is actually 50% higher than if they just choose to attend the mandatory team lift sessions.

Two years ago, I wrote an article on how we incorporate autonomy as part of our training process at Furman. Over these past couple of seasons, I’ve seen some developments within that autonomy training and I’d like to write in further detail about what’s changed in our process since then, what the athletes have taught me about autonomy, and how it’s the easiest way for our athletes and coaches to level up a development program.

Training Frequency

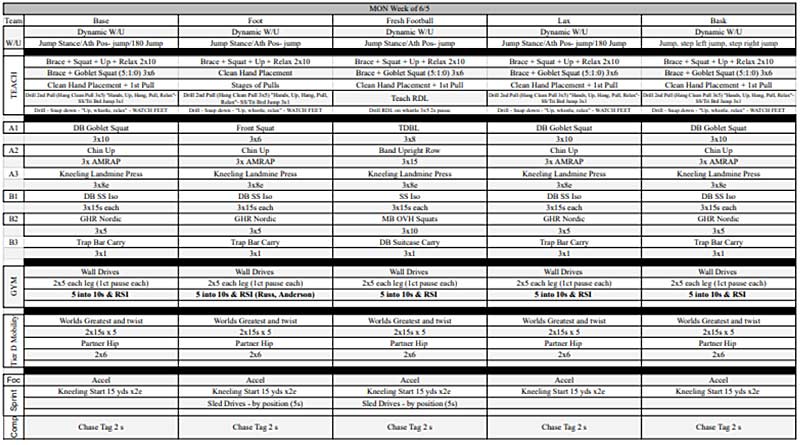

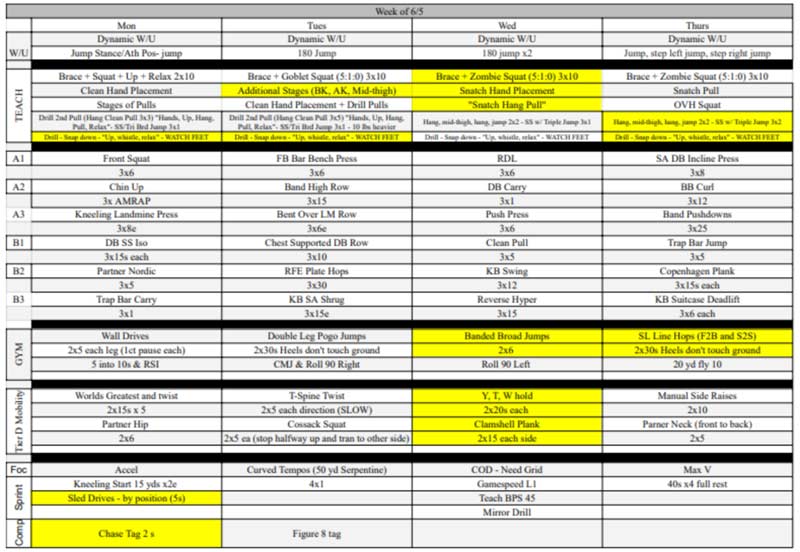

Summer training is one of the most significant uninterrupted phases of training for most Division 1 men’s basketball teams. For us at Furman, this consists of eight weeks of weight room sessions and on-court workouts from June to the end of July/early August. Within this time frame, I’m given three to four lift sessions a week. The biggest reason I’m able to train the guys more than that during the summer block is because I offer optional workout times/days and, within these sessions, give them the autonomy to choose which exercises and workouts they perform that day.

As a result of this, there is not a day I come into work that I’m not training an athlete, whether that is a Monday morning or a Sunday afternoon (yes, unfortunately our schedule in college athletics is rather varied). This is something that reflects our program’s culture of hard work, development, and deliberate improvement now model (#ALLDIN).

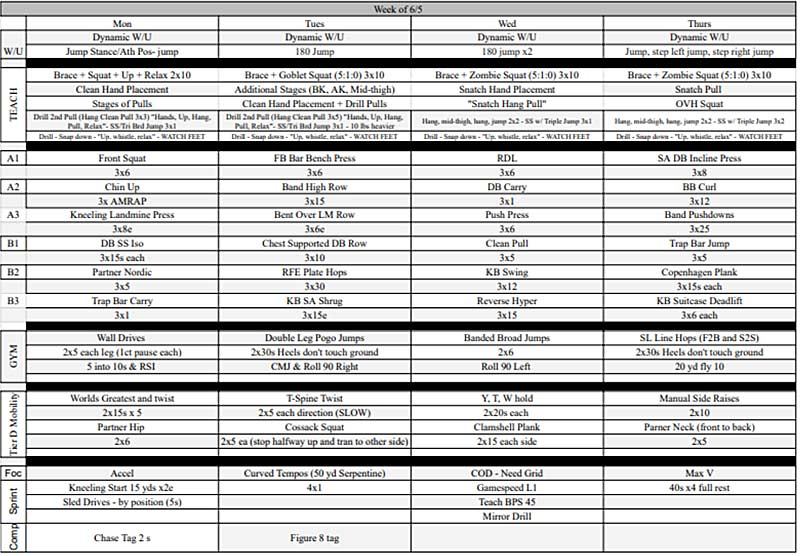

For the sessions that I’m given in which the players have to be there, I’m able to program holistically and specifically to the athletes’ needs. With the 13 scholarship players we have, I usually write between five and eight different programs. These mandatory sessions usually last one hour and are performed either with the full team present or in smaller lift groups based on class schedule.

Outside of these mandatory sessions, as noted earlier, I give the athletes the choice to get in extra work throughout the week. These sessions are optional and usually last 20-40 minutes, with the main difference being the freedom I give them to choose what they want to do in these sessions. If an athlete wants to train on a non-team lift day, it’s likely they will have an idea of what they want to work on for that lift, so I’m very comfortable letting them carry out this plan. After they complete that self-prescribed workout, the athlete feels they have taken a step in the right direction on their own personal development journey.

After they complete that self-prescribed workout, the athlete feels they have taken a step in the right direction on their own personal development journey, says @SCoach_Aldo. Share on XEmploying Athlete Autonomy

An example of an optional autonomy workout could be that the athlete wants to work on “power and feeling explosive” during this particular session. They enjoy Olympic lifting, so want to do some hang cleans and box jumps to “feel bouncy.” I suggest jump rope to warm up and a barbell complex before we do a more specific hang clean warm up. The athlete tells me they also want to “work some arms” after the power work. I ask the athlete how many sets and reps they want to do in the A series—I then use my knowledge of programming and their weekly load so far to discuss the best set and rep scheme. This is a great time to check in on the athletes training knowledge and briefly educate why performing eight reps on a hang clean isn’t ideal for power development!

After the reps and sets have been discussed, the athlete can perform the hang cleans and box jumps under my supervision. For the B series they want to do some biceps and triceps work, so I have them choose two arm exercises, we discuss sets and reps, and I supervise the B series. During the lift, I take the opportunity to check in on their diet, stress, sleep, life, etc. I may even jump in on the B series with them. At the conclusion of the lift, they’ve just completed a micro-dose of training stimulus (20-40 mins) between their larger doses of stimulus (~60 mins) on the mandatory lift days. This extra session is a win-win and is one of the biggest reasons why I love these optional autonomy sessions—what could have been a three-day S&C training week has now become a four-day training week.

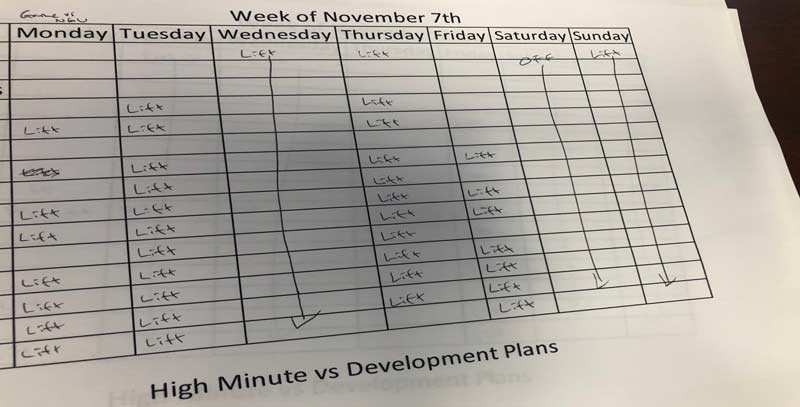

If I were to add up the extra sessions the guys performed this past year—which I in fact did keep a record of—the number would FAR exceed that of just the mandatory lift sessions. While this is an obvious statement, I would question you right now, how many optional sessions do you think your athletes actually perform with you? How could you increase that number? How do you get athletes to come in and train on days that aren’t mandatory?

If I were to add up the extra sessions the guys performed this past year, the number would FAR exceed that of just the mandatory lift sessions, says @SCoach_Aldo. Share on XOur model at Furman has shown that giving athletes autonomy on these extra days leads to a significant increase in buy-in and the perceived value of the weight room to their development, which then leads to increased participation in these sessions, which results in an increase in training frequency, which, when added up, makes a huge difference to the end result. It’s similar to how we view warm-ups. Working on physical capacities in the weight room and on court warm-ups for 5-15 minutes each day might not seem like much, but when this is added up over weeks, months, and years, that’s a lot of physical capacity development. The same can be said for these smaller lift sessions between the longer mandatory sessions.

For example, let me break it down to you with a summer training block:

- 8 weeks of summer training, 4 mandatory hour sessions a week, 0 extra sessions a week = 32 total S&C sessions

- 8 weeks of summer training, 4 mandatory hour sessions a week, 1 extra session a week = 40 total S&C sessions

- 8 weeks of summer training, 4 mandatory hour sessions a week, 2 extra session a week = 48 total S&C sessions

Going back to my opening point, if our jobs are centered on athletic performance development, how many training opportunities would you like your athlete to have that would contribute to meeting those performance development goals: 32, 40, or 48?

Now, I understand some of you may be scoffing at this and saying you’d prefer 32 quality sessions with adequate rest between than 48 sessions to better elucidate the imposed stress and compensating response to the S&C program. This is a valid statement for some professional athletes, especially those who compete in weight lifting competitions. However, for our college basketball athletes, a day off will likely involve them shooting on the gun, watching some film with a coach, going to the training room to get some treatment, and/or getting a stretch from me.

If we had a heavy leg day the day before and the athlete wants to come in the weight room for some core work and arm accessory work (yes, bis and tris), is that going to have a negative effect and blunt some of the training adaptation for the lower body from the previous day’s sessions? I’m hedging my bets by saying no, especially for low training age athletes—which is often the case with collegiate basketball players. They need as much time in the weight room as possible. Some post-lift foam rolling and stretching is always recommended, too, so their recovery could even be improved with this extra session.

Some post-lift foam rolling and stretching is always recommended, too, so their recovery could even be improved with this extra session, says @SCoach_Aldo. Share on XPreparing Athletes for the Future

Now, to add some more context to these optional autonomy lifts: will I be the primary coach in some of these sessions and tell an athlete what to do that day? Absolutely, it’s my job to know more than they do about the training process and athletic development. Will some athletes come in for extra sessions and ask me to give them a lift for that day? Yes. Will I get low-minute guys in extra during the season to keep working on certain physical qualities that will best prepare them to play when called upon? Yes. Will I get low-minute guys in on game days to do some power work to prep them for the game but also to give them some jump exposures so that if they don’t play, they’re getting some game intensity work in? Yes.

However, in order to really increase training frequency, in my opinion some autonomy sessions are needed. I’ve had athletes say “I’ll come in tomorrow (to the weight room), but only if I get to choose what I’m doing.” Come on in. I’ll take this 10 out of 10 times if it means an athlete gets an extra training session in. I’m certain everyone reading would too, but ask yourself: would an athlete feel comfortable asking you this? Or, would they fear being laughed at? In order to drive up training frequency, the weight room has to be seen as a place of development, not pain; as a place of improving on court performance, not an Olympic weightlifting hall or a military barracks where the consequence for asking a coach the wrong question results in burpees. Nothing screams insecurity or power trip to me more than athletes not having a say in their development in the weight room.

For me to think I know it all regarding athletic performance development is ludicrous. For me to think I know it all about a sport I played up until I was—wait for it—12 years old, is beyond dumb. Let the athletes take the wheel some days and work on what they want to work on. If you ask the right questions, you can learn a lot during those autonomy lifts. The athlete feels respected and trusted to give an opinion on their current program and whether they feel it’s making a difference in their physical capacities, and it gives you a chance to better understand their needs and what works for their body versus others’. If an athlete is always doing some type of plyometrics on these optional autonomy sessions, it’s likely they don’t currently feel explosive enough. Perhaps a conversation should take place to dive deeper into this. That talk could unearth something that has been on the athlete’s mind for a while.

Allowing autonomy also helps prepare the athlete for the next steps in their career. We’ve had numerous athletes play abroad and have some mandatory S&C sessions with their respective teams’ S&C coach. “Champions do extra,” though, right? So, if the player wants to get an extra session in and the S&C coach isn’t available, it’s up to the athlete to create a workout and execute it. If the countless optional sessions they’ve had at Furman can better prepare them for these workouts or a hotel game day workout, then great!

Allowing autonomy also helps prepare the athlete for the next steps in their career, says @SCoach_Aldo. Share on XGiving an athlete autonomy also, to an extent, shows you the athlete’s internal motivation and drive to succeed. With our athletes at home for May, it’s fun to see who reaches out to ask for programs, who sends me clips of them training, and who goes radio silent for the month! If for whatever reason they have a change in training environment, are they able to think for themselves and create a solid workout without me being there? I really hope so!

Programming with Autonomy in Mind

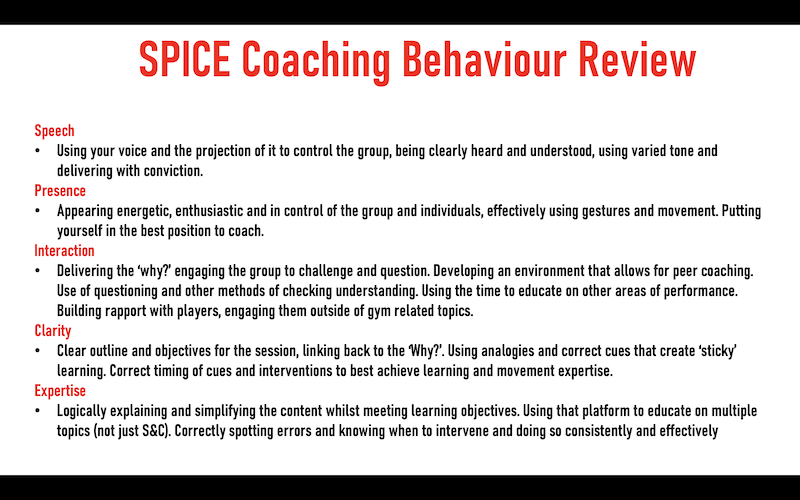

I take a lot of pride in the detail I put into my programming and the years that it has taken me to produce a solid, well thought out, holistic program. I also feel very proud when my athletes come in to train on optional days and I see them train with good form, give great effort, and carry out a solid lift. I see my coaching role as a teaching role; I want to transfer all the pertinent knowledge I have about performance to my athletes. If I haven’t taught them anything and have only instructed them on the what not the why, that’s a complete failure on my part.

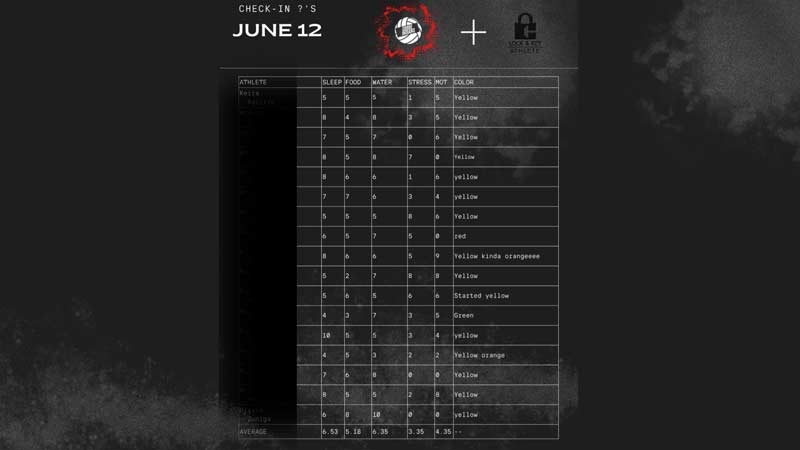

To keep track of the extra sessions, I create a very simple Excel file which labels the semester of training we are in, the players’ names, and which days they train. This gives me weekly and monthly totals. This information is great for holding athletes accountable to their goals and also keeps me in check with doing the same. If an athlete’s goal is weight loss, I have to make sure they are seeing me more often than the team lifts twice a week. It’s also a way to write notes regarding the stretches I performed pre- and post-practice so I can hold myself accountable to helping them best prepare and recover for practices/games.

I recently asked one of my athletes why he likes the autonomy lifts; he replied, “They are the most fun lifts, the best energy sessions.” He also said how he liked that—from my perspective as a coach—I then get to see what everyone wants to work on and maybe that can help me program for them.

This athlete always loves doing core work. Aside from the fact that he wants a six-pack, it’s helpful for me to see that and to keep challenging him with different core exercises. The athlete also referenced the best energy to our Saturday morning sessions in the summer. For some guys, that could be their sixth lift of the week. To have them in on a Saturday morning, often doing prowler sprints and racing against each other, is a great sign of where our culture is at.

As an added tidbit, my own workout on those Saturdays is to do one exercise of each of the athlete’s whiteboard workouts, for as many rounds as I can before our leadership guys call time on the lift. It’s a great way for me to interact with the guys and gives me an opportunity for some sweat equity with them! As to why he feels they are the best energy sessions, it makes sense that everyone’s spirit is up and they are having fun, they did after all choose to be there that day to get extra work in. Letting them be the DJ on my Apple music account probably contributes to that extra energy, too!

Working out with the team is a great way for me to interact with the guys and gives me an opportunity for some sweat equity with them, says @SCoach_Aldo. Share on XGame Day Lifts

On rare occasions, I have a real lightbulb “wow” moment when coaching the team. One of those moments happened in-season this past year. I have an optional lift every home game day that takes place an hour before we meet as a team for film. It’s open to everyone. My walk-ons and redshirts always come, and low-minute guys come also. One particular low-minute guy had struggled in the weight room his first year with us; his effort was below standard and we had many a conversation about improvement and being held accountable to one’s body of work.

Fast forward to this season and I’m having to stop the athlete from lifting for too long during one of his autonomous game day sessions, in fear of a residual fatigue effect for the game later that day. He didn’t want to stop—he wanted to keep training. From being in a mental space of not enjoying the weight room and not applying himself fully, I’m now having to take the dumbbells out of his hands and tell him to get a stretch before heading to film. I wonder if he would have had that attitude of self-improvement that day if I had created the workout for him? Self-motivation is a beautiful thing when you’re in the driving seat of your development, not the passenger seat.

Self-motivation is a beautiful thing when you’re in the driving seat of your development, not the passenger seat, says @SCoach_Aldo. Share on XBasketball Autonomy

Basketball athletes show autonomy most days they are in the facility. Every time they choose to shoot on the gun or with a partner, they are making a decision to work on an area of their game they want to improve. They may decide one day to try and hit a certain number of consecutive free throws, or work on some ball handling; again, it’s a decision they get to make regarding which skills to improve. So why can’t the same thing be applied to weight room work? Why can’t the athlete make that decision to work on a specific area a couple of times a week?

Recovery Autonomy

Let’s all assume you have a trustworthy, hard-working athlete with a great attitude. I am a firm believer that this athlete inherently knows what works for them from a recovery perspective. Nowhere is autonomy more impactful and prevalent than in an athlete choosing which recovery modality to use to reduce soreness and make them feel more recovered before the next session. Take, for example, an athlete who hates ice baths; they stress them out and they can’t sit it one for longer than a minute. Compare that with an athlete who tolerates them well and can be in there for 15 mins.

Recovery is all about downshifting the sympathetic nervous system and upregulating the parasympathetic nervous system. You want the athlete relaxed, you want nasal breathing, you want to reduce their stress to encourage effective recovery. The athlete you made have an ice bath is all tensed up hating the ice bath; they don’t want to be in there and would probably name a few alternative therapies that would help them recover more optimally.

As much as I enjoy giving the athletes a say in their physical development, I would argue the case even more so for giving them a say in their recovery. Giving them the choice and some decision making will again lead to further questions and understanding of the coaches’ and trainers’ point of view, which will contribute to a more effective individualized holistic athletic performance program for that athlete.

As much as I enjoy giving the athletes a say in their physical development, I would argue the case even more so for giving them a say in their recovery, says @SCoach_Aldo. Share on XConclusion

As a strength and conditioning coach, I want to be a facilitator for student development, encouraging self-discovery and ownership with all aspects of their learning and training. Our aim should be creating an environment that allows room for experimentation, reflection, and growth.

Give it a try—for your next optional session, when an athlete texts you and wants to train, ask them what they want to work on. Say that you are there if they need guidance and that the weight room is open and available for whatever they want to work on. Do let me know how it goes. I’m raising my morning coffee in a toast to autonomy. Give the athletes a say in their development and watch the buy-in and results reach a new level.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF