The high school space may be the fastest growing and most controversial place for the use of velocity-based training. This shouldn’t be a surprise, considering high schools probably have the widest range of coaching philosophies, experience, and education in the field of human performance, as well as a wide variance in athlete skill and training age.

The argument that an advanced protocol like VBT has no place in training for developmental athletes at the high school level is a strong one. Although more-experienced high school athletes may reach a point where they are ready for advanced technology, is it really necessary for the majority of student-athletes to dip into the technology pool? The relative ease of pushing a strength adaptation through simple, slow-paced progressive overload makes it easy for many coaches to dispel the idea of using an additional tool in that process.

There is no doubt that traditional progressive overload will get you where you want to go, just as I can eventually get to California by hopping in my car and starting to drive west. The optimal way of making that trip, however, is to use a map to get there as fast and directly as possible. Leave the old, folded-up map behind and upgrade my tool of choice for this trip to my phone equipped with GPS? Even more precision and saved time.

I propose that not only is VBT something that can be used to optimize the training of your advanced athletes, but if used correctly, it can become an indispensable tool in the development of your student-athletes.

Technology for All Levels

The common misconception with technology such as VBT is that it can only be useful for higher- level, more advanced athletes. In my experience, however, the coach implementing the technology is most often the limiting factor in that situation. The time to use VBT (or other technologies) isn’t when the athlete is strong enough or fast enough or when they have reached a certain randomly-selected training age—it’s when the coach is experienced enough, talented enough, and willing enough to be a great practitioner and excel at the art of coaching.

The time to use VBT is when the coach is experienced enough, talented enough, and willing enough to be a great practitioner and excel at the art of coaching, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XThe key factor is to understand that velocity-based training is a tool. Webster’s definition is fitting: A tool is a device or implement used to carry out a particular function or aid in accomplishing a task; a means to an end. As a tool, VBT can carry out the particular function of optimizing training and accomplish a multitude of tasks that help the coach build precision and intent while assisting the athlete to become more technically sound (at least when utilizing Vmaxpro).

VBT helps us to weaponize and gamify the means to all of our ends in this field: transfer of training in an optimal manner. One of the big advantages of using Vmaxpro over other devices is it truly helps the athlete understand the why behind their training. But that why—as well as the how—must already be mastered by the coach or else VBT is a tool best left in the toolbox, regardless of the level of the athlete.

Bar Path Is a Big Deal

There was definitely a time that I too believed using VBT was just for my most advanced athletes from a leveling perspective. That changed after a face-to-face conversation with one of my mentors in the field, who told me that using a velocity floor would allow athletes with lower training ages to find optimal loads for strength training without rushing these inexperienced lifters into a 1RM test. Learning how to train with heavier loads with a guidance system and a way to place a governor on exactly how intense the workout can get is useful in the development of less-experienced athletes. That conversation sent me on a quest to find a method to use VBT technology as a teaching tool and an important part of our overall progression.

When I was introduced to Vmaxpro, within minutes of using the product I recognized that not only could we use the device as a way to set loads and teach intent, but also as a way to teach technique and educate the athlete. Vmaxpro provides instant bar path and bar displacement feedback; not only instant, but with video-game-like graphics.

I had been told about the bar path feature prior to use, and at first, I honestly didn’t think it was that big a deal. My experience with bar path was mostly with the Coach’s Eye app and Olympic lifts: It was time consuming and individualized, and the post-workout feedback made that a less than optimal tool when dealing with team sport athletes. I quickly recognized that instant bar path feedback during the workout could be a seriously powerful tool in the development of our young athletes.

I quickly recognized that instant bar path feedback during the workout could be a seriously powerful tool in the development of our young athletes, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XThe device itself can act as an assistant coach simply by providing technique feedback. If we teach our athletes how to use this tool, it allows the process to be less coach-driven and more athlete-driven, even from a technical aspect. I could use this feature to meet my athletes where they were.

The VBT Hook

My first step in developing my process of using VBT as a big part of our progressions for younger athletes grew out of a process that I had already been using but felt VBT could optimize. I was in the process of transitioning our freshman football players from the 1×20 program they had been following since middle school. We work our athletes from 1×20 to 1×14 to 2×8. Eventually, we begin to split off our “big rock” movements into a modified tier using a 5×5 progression.

Day One of that week, I told our athletes that we would be doing sets of five and working up to a 5-rep max—they were excited, as this was the first time I was going to let them load the bar freely and work up to a true rep max lower than 8. The caveat, however, was that I would be attaching a device to the bar that would give us the “speed” the bar was moving. They were allowed to load the bar until their set average was .35 m/s.

Of course, at that point, they all looked at me and had no idea what I was talking about. Mostly, they were just happy I had used the word max. So I let them get to it. As we all know from working with teenage males, they have one goal when lifting: put as much weight on the bar as possible. After a couple sets, I could already see the velocity dropping, so I stopped the entire group.

It was time to educate them.

I gathered them in and asked, “what did you notice happening with the number popping up for each lift as we added weight?” Soon, a hand went up. “The number goes down the more we add.” Hook #1 in place. “So, if .35 is the lowest we can go, how can we make sure we lift the most weight for five reps?” Soon a hand went up again. “We need to make sure we are moving the bar as fast as we can.” Boom. In that instant, every athlete (whose single purpose that day was to lift as much as they could, same as every day) realized that intent mattered. The faster they move the bar, the more weight they can add.

The impact was immediate. I let them go through another set before I stopped them a second time. Hook #2 is the real secret sauce, and it was time. I called the group back again and pointed to the TV screen, which was mirroring one of the iPads. On the screen, I had the bar path from an athlete for a few back-to-back reps: one rep where the bar path was outstanding and one that was not so good.

“So, this is two reps, in the same set, from the same athlete at the same weight. We already know that the heavier the weight, the slower the velocity, correct?” I asked, and all the athletes nodded. “Well then why is one rep .54 m/s and one .44 m/s? Did he get weaker really fast? What’s different?” There was silence for what seemed like 30 seconds, before one of the guys said “Coach, the line is different. The faster the rep is, the more up and down.” Boom. Again. He had said exactly what I hoped he would.

“What’s that mean when it comes to adding as much weight to your 5-rep max as we can today, guys?” I asked. The answer changed the game for our young athletes. “It means if we use better technique but move the bar as fast as we can, we can lift the most weight possible.”

Within five minutes, we had a room full of ninth-grade males watching the bar path and talking bar speed, discussing technique and how to load the bar optimally, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XOur athletes only cared about how much they could lift. As coaches, we mainly cared about technique and intent. By making those two things very important in the eyes of the athlete, we had met them where they were. Within five minutes, we had a room full of ninth-grade males watching the bar path and talking bar speed, discussing technique and how to load the bar optimally. Educated and motivated athletes who care about the things that will actually transfer to the field is a powerful place to be.

Squat Depth Made Easy

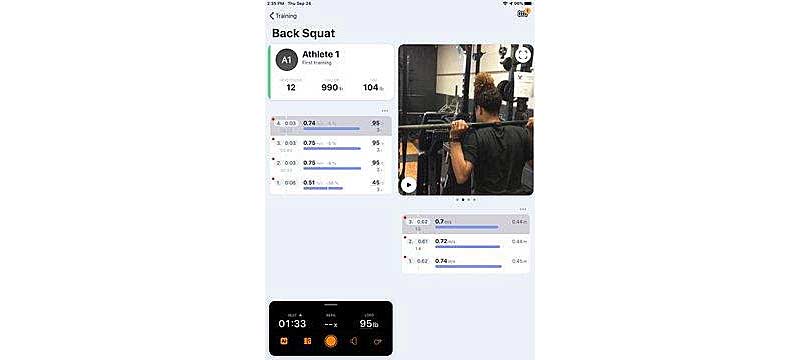

The very next workout, we decided to ramp up our squat progression. This was not by choice—our head coach asked me to provide him a pathway to get a 1RM back squat number on all our players, including our freshmen. While I had my concerns, we went forward. I knew the Vmaxpro would be a powerful tool in moving our freshman football athletes into the full use of the barbell bilateral back squat: not only would bar path play a huge role, but the live bar displacement feedback would as well. The bar displacement metric would allow us to set a numerical metric for a mutually agreed upon parallel squat depth.

We began our warm-ups with an empty bar, and I had each athlete squat to a depth that they, their rack team, and I all agreed was an acceptable depth. We then had them get to that depth while staying in a ribs stacked position dictated by the live bar path feedback. Not every athlete can get into a perfect, stacked squat but you can ensure optimal performance and spot weakness that may lead to excessive lean and potential injury issues by using bar path as a tool.

We followed a very similar process to the previous session, allowing the athlete to load the bar based on a .35 m/s set average floor. One of the things we agreed upon as a staff was that we would stop each athlete at “technical failure.” Using the feedback from the Vmaxpro to not just set or project load, but also to assess for the squat depth and technique, we were able to judge technical failure with a precision the naked eye does not provide. The coach, the athletes, and their training partners can actually see on the screen where performance begins to drop below the desired level for that session.

Using the feedback from the Vmaxpro to assess for the squat depth and technique, we were able to judge technical failure with a precision the naked eye does not provide, says @YorkStrength17. Share on X

The biggest takeaway from this way of using VBT is we do not just present the athlete with the output and say “get to .35 m/s.” We also teach them the why behind the process that gets them to that final output. They learn very quickly how to look at the feedback and adjust to train with optimal technical skill and intent. Simply providing them with a video of themselves and the velocity and/or power outputs is no different than popping on game film for football players who you have not educated on the process of learning from film study.

Moving Forward in the Progression

Now that we have educated and motivated athletes who understand how to use the feedback, we can move to the next step in our progression for the intermediate athlete: using APRE (autoregulatory progressive resistance exercise) combined with VBT to take strength development to new heights.

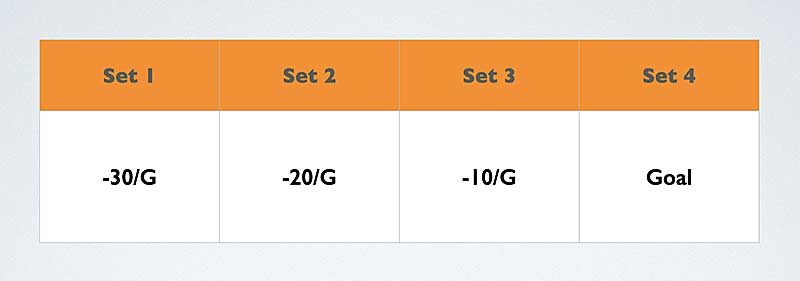

We run our 5×5 program using just the mean velocity to adjust loads and let the athletes get the feel for how VBT works. Now, we want to add one more layer to that. We have the athlete work up to their previous 5RM at a .35-.45 m/s range. (We moved to ranges from floor for this step, as it is much easier for the athlete to get to that range than to an exact number.) They have three sets of five to get to that goal load using this protocol:

We use the Vmaxpro to measure sets 3 and 4. Set 3 is used as a monitoring set. We tell the athlete if they are above .55 m/s or below .40 m/s on that set to let us know so we can discuss a potential adjustment to the original goal. This is just another important step in the education of our athletes on the VBT system.

We use 85% as the projected goal to start the process, but once we have a goal weight based on mean velocity and adjusted, we simply use that as the goal weight for set 4 of the following week. This combination of VBT and APRE has proven to be a superior process for driving the strength adaptation process for our intermediate athletes.

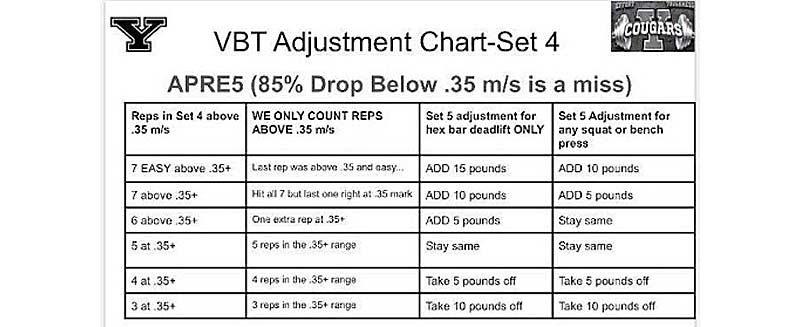

Once they reach set 4, they will do a maximum of seven reps that must be above .35 m/s. Once they either drop below that velocity or hit seven reps above it, they use the following chart to adjust their load for their final set of five reps. They DO NOT use Vmaxpro for set 5. They simply use it to adjust and attempt to get five reps at that adjusted load.

If they make five reps? Then that is their goal weight for next week’s set 4. If they do not? Then set 4 remains the goal weight for the following week.

Bonus Material

We run that 5×5 program for our “big rock” movements of squat, hex bar pull, and bench press for most athletes until the end of their sophomore year, when they move into our advanced level. During that time, we begin to add in some “bonus” material that helps to tighten up the athletes’ experience even more.

Percentage of Time of Acceleration

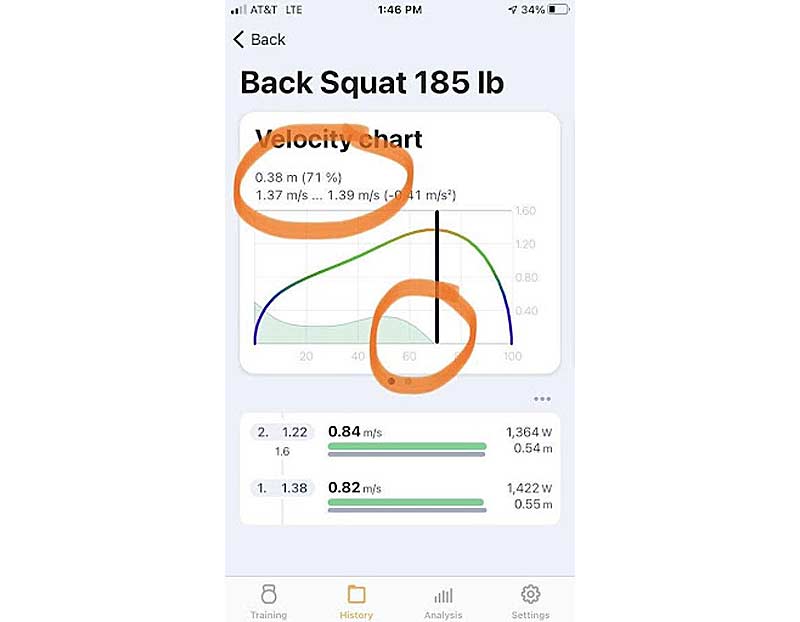

The Vmaxpro not only builds out a velocity profile for each athlete and each exercise, it does so for each individual repetition. What we can get from that information is what percentage of the rep the athlete is actually accelerating the bar. The developers of Vmaxpro informed me that based on the studies they have done, the sweet spot for acceleration of the bar producing the best outputs of velo and power is at or above 70% of the total time of the rep.

The developers of Vmaxpro informed me…the sweet spot for acceleration of the bar producing the best outputs of velo and power is at or above 70% of the total time of the rep, says @YorkStrength17. Share on X

While this isn’t as quick to look at live as bar path or displacement, it has proven valuable for me as a coach to follow behind and quickly check to see which athletes are finishing their rep and which need additional cueing or help. My go-to cues are:

- Throw your fist through the ceiling on bench press.

- Squeeze the glute at the top of the squat.

In our situation, both of these have shown to improve the bar acceleration time. As your athletes begin to get closer to “strong enough,” and you begin to slide their programming more from the force side of the force velocity curve to focus on speed and power, they will be ahead of the game from a power development standpoint with this technique.

Using “Peak Power” to Drive Intent

Some may argue that peak power is not a great metric to use in a strength movement. My answer is “back to your lab.”

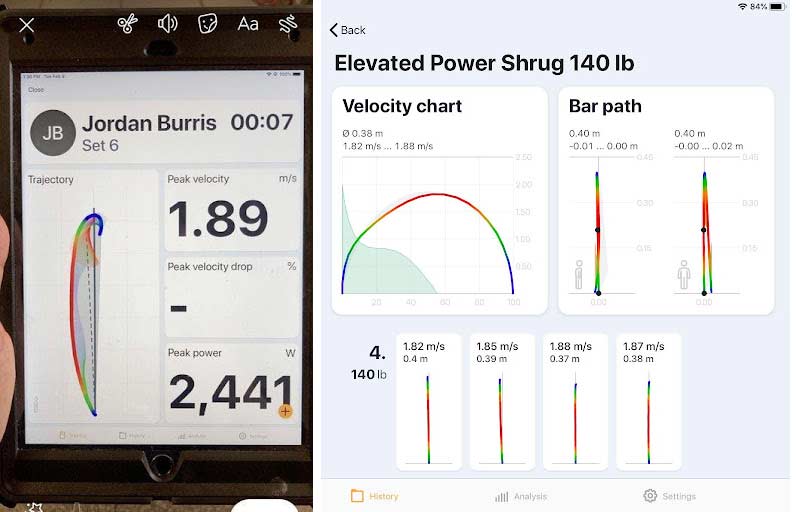

Peak power is a GREAT metric from a practical standpoint and highly effective in developing powerful athletes. While I would agree that peak power is not something we want to use to drive adjustments or loading parameters, it’s what mph is to speed development—and, true, some coaches are not fans of that either. I say who cares what they think. Mph is not a metric we use to drive any programming, but it is one that the kids love and want to see increase. Show me an athlete who has been stuck at 19.7 mph and breaks that 20 mark for the first time, and I will show you a highly motivated athlete.

Peak power on a strength lift is the same. It’s a motivational tool that drives them to move the bar full of plates as fast as possible. If they do that chasing peak power, but mean power, mean velocity, and projected 1RM all increase, then why in the world would I not utilize that?

Peak power on a strength lift is like mph for speed development—a motivational tool that drives athletes to move the bar full of plates as fast as possible, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XWith Vmaxpro, you can get metrics on up to two data points per rep recorded. In our strength movements, we track mean velocity (0.81 m/s in top rep of image 7 below) and peak power (2,172 w in same rep) on the instant feedback screen in the app. Guess which one gets the kids the most excited? Speed kills and our athletes see peak power as speed. As a coach, I use the mean velocity as a metric to drive adjustments. Peak power is the metric that drives intent in our kids.

While I have no idea exactly what a great peak power is globally, I do know what we are seeing. Anything over 2,000 watts has proven to be a great number for our athletes. When they hit that, it brings a similar reaction to a sub 1.0 fly 10 or 4.5 40-yard dash. Pure excitement, some fun-loving trash talk, and now a positive part of our team culture.

As with any technology, the key to using VBT doesn’t solely lie in the experience of the athlete. It truly depends on the coach and the coach’s ability to not just use the tech but understand why they are using it and how to use the metrics and data feedback to improve and optimize the athlete’s experience.

This article is not a comprehensive look at how I use VBT, nor is it a user guide to all the features of the Vmaxpro. This is just a snapshot of both that I hope inspires coaches to either utilize their knowledge or pursue the capability of not just using VBT but making it a friend and ally in the pursuit of optimal performance for all levels of athletes in your program.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF