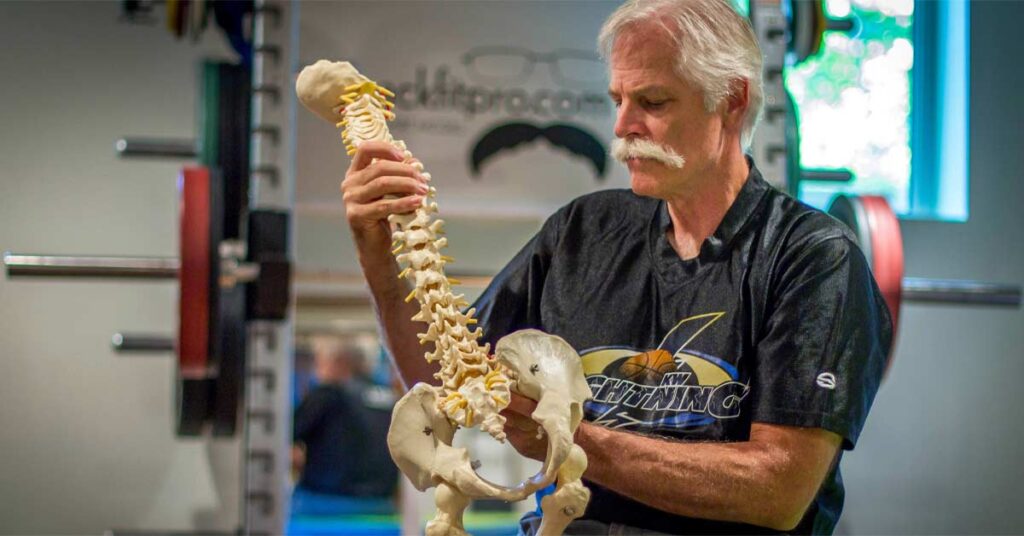

If you Google “Back Pain Guru,” chances are Dr. Stuart McGill’s name will appear at the top of your search. He earned it.

A distinguished professor emeritus who taught at the University of Waterloo for three decades, McGill has devoted his life to studying biomechanics as it relates to back pain and athletic performance. Along the way, he wrote 245 peer-reviewed scientific papers and several books for healthcare professionals and the general population. Dr. McGill has moved on from academia to become the Chief Scientific Officer for BackFitPro, Inc.

Freelap USA: Sprinters often perform hundreds of reps in spinal flexion exercises during a single week. What are your major concerns about these exercises?

Dr. Stuart McGill: Exercises are simply tools to achieve specific goals. After identifying those goals, I always try to use the best tools to accomplish them, taking into consideration the risks versus rewards of specific exercises.

Elite sprinters like Usain Bolt use the abdominals as short-range, stiff springs that enable them to transfer force across the hip joint. This is how the abdominals should be trained. With a sit-up, only 20% of the flexor torque comes from the rectus abdominis.

The disks are not ball-and-socket joints like the hip but follow the mechanical principles of a fabric. They contain collagen fibers that form a fabric-like concentric ring around a pressurized gel. If you move this structure forward, over and over, under concentric load, these collagen fibers will slowly delaminate. This delamination leads to disk bulges.

Instead of sit-ups, assume a push-up position and walk your hands out, then back. That exercise produces 100% neural drive to the rectus abdominis and anterior core and won’t delaminate the collagen of the discs.

Freelap USA: Elite sprinters often spend 30 minutes a day or more stretching. Are there any problems with extensive static stretching on the spine, and is yoga valuable?

Dr. Stuart McGill: Stretching is a tool used to tune the body, and it should be very specific. Yoga is non-specific, but its poses are specific, so we might use a particular pose from yoga to achieve a specific goal.

We don’t recommend runners stretch their calf muscles before training. I haven’t tried this with sprinters, but I have with marathon runners. The runners who didn’t stretch had a faster first five miles because stretching interferes with the efficiency of the nervous system. Let me expand on this point.

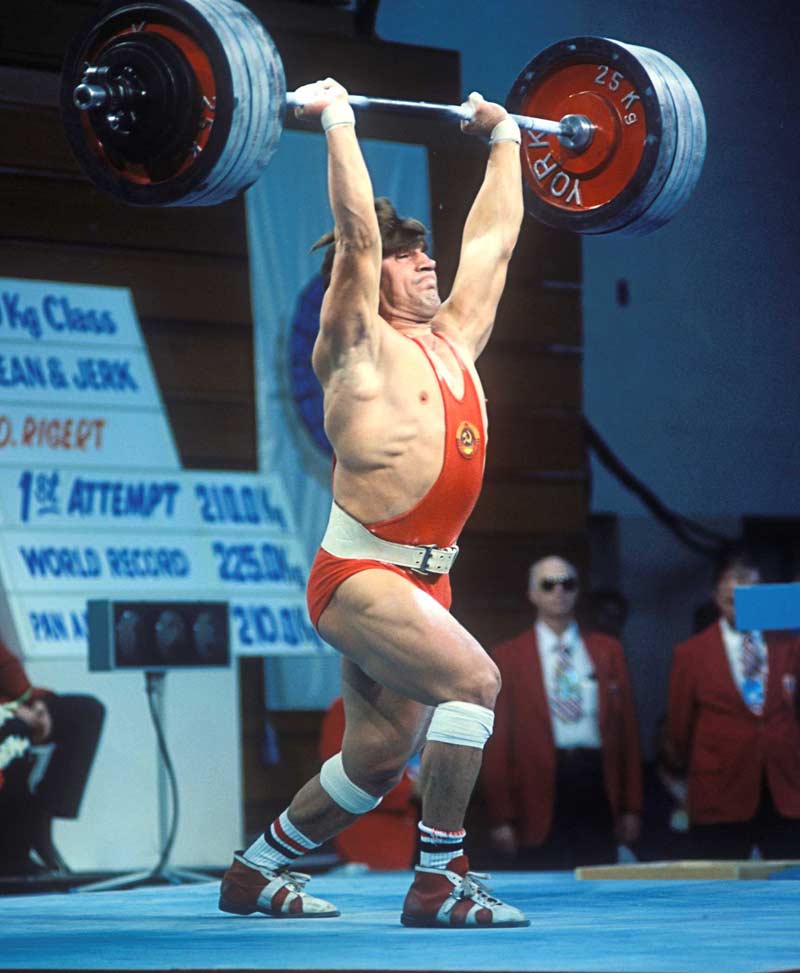

Sprinters are elastic, pulsating athletes. The fastest sprinters are the fastest relaxers, meaning they get their muscles to fire up quickly and then relax quickly. The same goes for weightlifters. Russian sports scientist Leonid Medvedev showed that the muscles of elite weightlifters relax six times faster than the average Muscovite walking around the street. Weightlifters stretch, but their stretching occurs rapidly while they are training and under load.

If there’s a restriction affecting performance, it’s essential to determine what tissues should be stretched. The specific location of the restriction should inform the specific stretch they need. Share on XIf there is a restriction affecting performance, it’s essential to determine what tissues should be stretched. If a sprinter needs more range of motion in hip flexion, they need to be tested to determine where the restriction occurs, such as in the iliacus or psoas muscles. The stretch for the iliacus is different from the stretch for the psoas.

Freelap USA: Two popular exercises among strength coaches are the hip thrust and the Bulgarian split squat. The hip thrust has been promoted as an exercise to prevent back pain, whereas you have reservations about the risks of the Bulgarian split squat. What are your thoughts on these exercises?

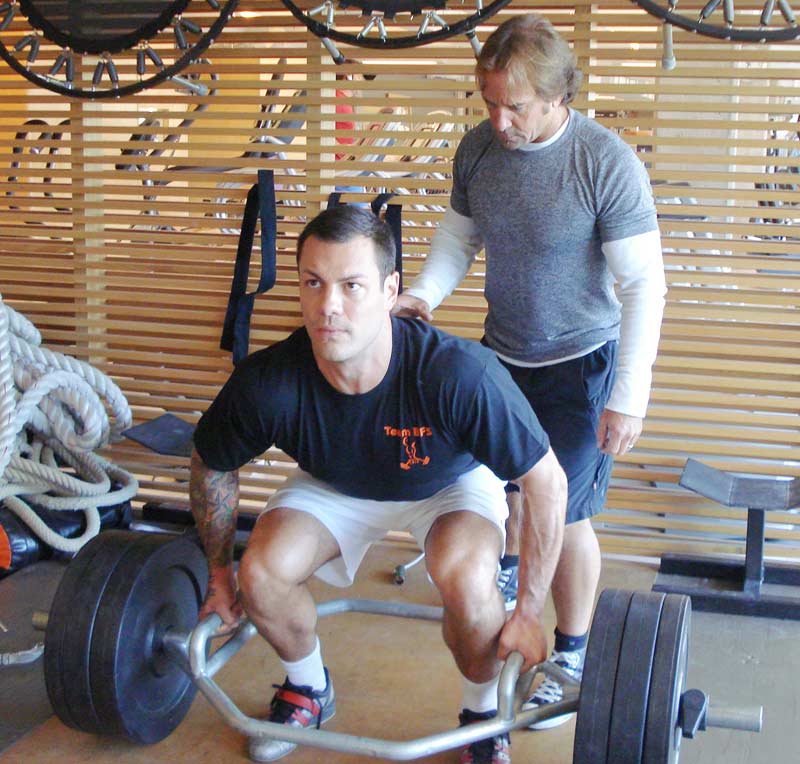

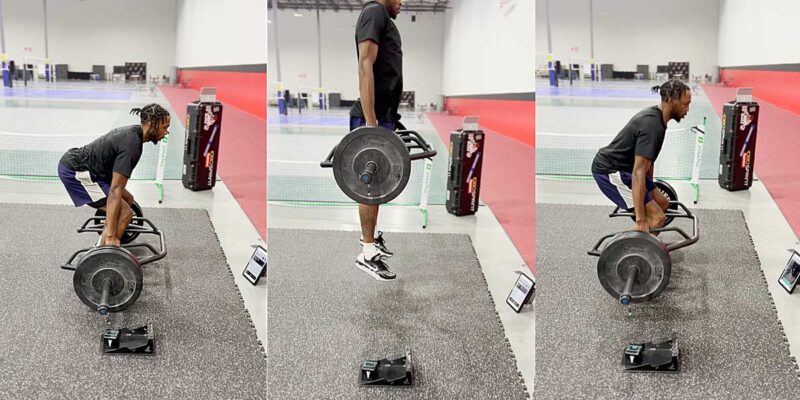

Dr. Stuart McGill: I’m one of the few individuals who has measured the mechanics of the hip thrust, and I found that technique really matters. If you want the load to target the glutes, the feet must be flat on the floor, and you should try to push your feet away from you with knee extension. Also, when you go especially heavy, you bring in auxiliary muscles to help complete the movement.

Next, in my world, there is no such thing as non-specific low back pain. If someone has back pain, you must assess the individual to determine the specific mechanism causing pain.

In my world, there is no such thing as non-specific low back pain. If someone has back pain, you must assess the individual to determine the specific mechanism causing pain, says @drstuartmcgill. Share on XWhen you say the hip thrust protects against low back injury, my first question is, “What kind of injury?” because you must know your training target. We’ve seen athletes who said, “The hip thrust hurt my lower back.” We’ve also seen athletes who said, “That exercise helped my lower back.” The hip thrust may be the best tool for one lower back issue, but not for all of them.

I’ve seen a sprinter and several tennis players who had sacroiliac pain from doing loaded split lunges, but the issue is not with the spine but with the pelvic rings (the two ilia plus the sacrum). The twisting, back-and-forth motion of this exercise can stretch and loosen up the sacroiliac joints when programmed with too much volume and too much load. This instability can cause sacroiliac pain and reduce an athlete’s hip’s ability to produce and transfer power to the thigh. Genetics are also involved. People with deep hip sockets will create more SI joint stress with deep split lunges.

Freelap USA: What are the long-term consequences of the dynamic twisting motions in sports such as the discus? Are these athletes, especially those in the masters’ divisions, setting themselves up for chronic back pain with these sports?

Dr. Stuart McGill: I’ve seen Olympic medalists and masters athletes in the throwing events. With these athletes, we often see arthritis on one side of their spine and not the other. Of course, I’m giving a biased view, as I only see the failures.

When a back-pained discus thrower asked for a consult, I would ask them how many times they threw in a session. If they said, “Oh, a hundred times,” my response would be, “Well, no wonder you have pain with the repeated concentrated stress—the cumulative trauma is running way ahead of the adaptation rate!” My advice would be to have them throw less and work more on foundation strength training in the weight room with auxiliary exercises—that’s Charles Poliquin 101.

Regarding the Russian twist to strengthen rotation, I’ve found that you can do this exercise for three to five months and get really strong at twisting. After that, the collagen on the rings of the discs starts to delaminate. However, there is a spectrum of how resilient individuals are to these twisting exercises—and, as you know, elite athletes are special.

Freelap USA: Are regular chiropractic adjustments a sensible treatment for the spine, even if there is no pain?

Dr. Stuart McGill: I’m not a fan of adjustments unless that has proven to be the best tool, and I’m one of the few guys who has measured what goes on during chiropractic manipulation. An adjustment may reduce an existing muscle spasm by creating a sympathetic response, but there are other ways you can create that response. By the way, sometimes an adjustment can also cause a muscle spasm.

I’m not a fan of adjustments unless that has proven to be the best tool, and I’m one of the few guys who has measured what goes on during chiropractic manipulation. The problem is that manipulations are non-specific, says… Share on XThe problem is that manipulations are non-specific. In the lab, we did a study on chiropractors manipulating L5 and L1 to determine if their technique hit their target. We found that their adjustments were non-specific, as there was only a statistical chance that they hit their target. We also tested an osteopathic teacher, and he had the same accuracy score as the chiropractors.

When I was at the experimental research center at the university, we saw patients who reportedly were injured by chiropractic, and I’ve had experiences with that myself. But there’s another side of the coin. I saw an Olympian from a power sport with back pain. We had success with changing the program, but he had a spasm in a specific section of the quadratus lumborum muscle that I didn’t have the skills to release. I sent him to a manipulation guru, and he did a targeted adjustment over three sessions on that specific snag in that muscle, and he had great success.

Many world-class sprinters travel with their body workers, massage therapists, chiropractors, or whoever. So, these special athletes see some value in tissue work to unleash top speed and performance.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Alex Roberts is the Strength and Conditioning Coach at R. Nelson Snider High School in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In this role, he’s responsible for the year-round athletic development of all student-athletes. Coach Roberts’ main responsibilities are teaching strength training classes during the school day, leading after-school training sessions, and running the summer strength and conditioning program. He holds a Master of Science in Kinesiology and is CSCS certified through the NSCA.

Alex Roberts is the Strength and Conditioning Coach at R. Nelson Snider High School in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In this role, he’s responsible for the year-round athletic development of all student-athletes. Coach Roberts’ main responsibilities are teaching strength training classes during the school day, leading after-school training sessions, and running the summer strength and conditioning program. He holds a Master of Science in Kinesiology and is CSCS certified through the NSCA.