Many elite sprinters, notably many Jamaicans, drag or scrape their toes during the second stride of a sprint. For some, that drag occurs on both the first and second strides, and hurdler Lolo Jones even dragged during her third stride. Proponents of toe dragging say it helps ensure low recovery of the leg, which many think to be efficient during the first strides; they also point to increases in ground contact time, which allows for creating more force and a longer stride. Some will even say this provides a foundation for maximizing top speed (max velocity).

It is obvious to me that toe dragging does not represent a best practice in regard to the success of the total race, says @TheYouthTrainer. Share on XIt is debatable whether or not dragging the toes is a good technique. While I am not in favor of toe dragging, I also am not in the camp of I just don’t get it. My understanding of what is mechanically sound for the first three steps allows me to see what toe dragging achieves, but it is obvious to me that it does not represent a best practice in regard to the success of the total race.

Biomechanics from the Start

Ralph Mann stated in The Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling: “The main goal of the start is to produce maximum Horizontal velocity coming out of the blocks and during the next two steps.” This is why he considered the first three steps as the start. Mann also gives us another way to look at the start, saying, “the start consists of three very short Air Phases. These are performed to minimize the Vertical emphasis while maximizing the time on the ground and, thus, the ability to produce the forces to accelerate the body down the track.”

With this in mind, it seems redundant to intentionally drag the toes to facilitate even longer ground contact. Especially with Mann adding, “Although the ground contact time is largest during the start, the better performers minimize this result.” To me, this means that we need to focus on coordinating movements that are natural and fundamentally sound and train key abilities (such as eccentric strength) to maximize results.

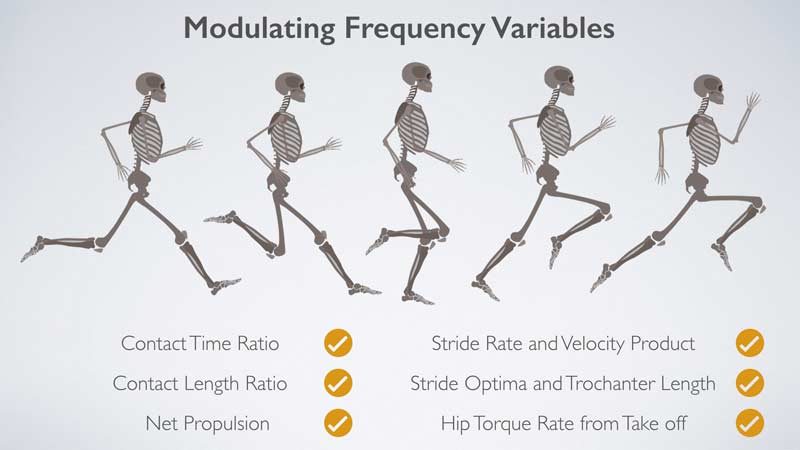

Let’s take a look at a few more fundamental biomechanical aspects of sprinting. Frans Bosch and Ronald Klomp, in the book Running, stated, “During the transition from start to acceleration to speed, there is a progression from long to brief ground contact times, from explosive to reactively working muscles, and from many to a minimum number of rotations for which the runner must compensate.” During a successful sprint race, there are also other transitions that the athlete evolves through—i.e., from piston-like strides to strides that are like a cycle, and transitioning from when ground contact time exceeds time in the air to when time in the air is greater than ground contact time. Stride length should progressively increase during acceleration if coordination and timing effectively apply forces to the ground.

I maintain that dragging the toes disrupts all of what I allude to and explain above, such as the naturally occurring transitions and the accompanying rhythm and timing.

Practice Methods

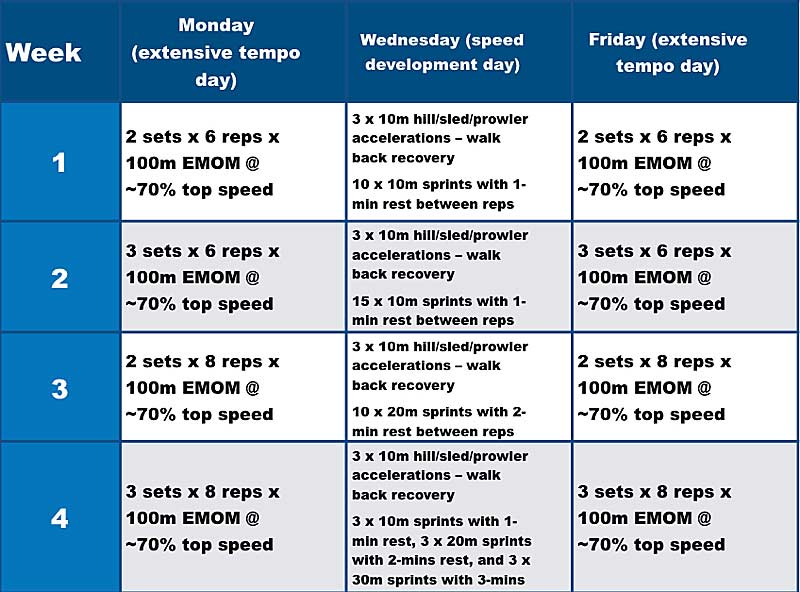

Competitive 3- to 10-meter sprints provide good opportunities for athletes to work on beginning to accelerate optimally, and once ready, 20-meter sprints do as well. These short sprints can help develop an effective rate of acceleration and efficiency of movement. Very good sprinters are typically able to continue accelerating beyond the 30- to 40-meter mark.

With this in mind, you want athlete A, who’s running a competitive 10-meter sprint in training, to understand that being in front at the 3- to 5-meter mark—but being caught by athlete B at the 10-meter mark—means that if the rates of acceleration and efficiency of movement stayed the same, athlete B would be clearly ahead and pulling away by the 20-meter mark. Dragging the toes and pushing off forcefully into the next stride may give a sprinter a temporary advantage, but at what cost to the rate of acceleration and efficiency of movement? How much energy could have been saved by not dragging the toes and instead utilizing eccentric strength and coordinating natural movements to build upon momentum and optimize acceleration?

Dragging the toes and pushing off forcefully into the next stride may give a sprinter a temporary advantage, but at what cost to the rate of acceleration and efficiency in movement? Share on XStride #1

After using the starting blocks to explosively project the hips and body out to about a 45-degree angle, to complete stride one the leg that is in the high knee position should be aggressively pulled down and back so that the foot lands under the hip—but that landing point will be behind the body’s center of mass (more of the body will be in front of the landing point than is behind it). As Ralph Mann put it: “placing the body in a position to produce maximum horizontal (down the track) acceleration.” Also note that with each ensuing stride (stride three and beyond), the landing point of the feet get progressively closer to being under the center of mass, until at some point in the race the feet land in front of the center of mass.

I like to have the athletes do some sprints from a standing start to develop that pattern of movement. This can teach them how to effectively bend, hang, coil, and project themselves, only having to concern themselves with two points of contact with the ground: the feet. For the standing start, the weight should be centered over to the side where the bent front leg is, while putting some muscles on load to enable them to explode into a good first stride. If coming from a standing start, the athlete will then be able to attempt to execute stride two without as much of a landing force as would be present if coming from a three- or four-point start.

I believe it is a mistake to underestimate how good standing start mechanics contribute to overall sprint technique. When pushing off for the first step, while coming out of a stationary standing start, the rear foot pushes, and there is a subtle movement of the front foot before it joins the pushing of the rear foot for the double leg drive. This preliminary movement of the front foot during a stationary standing start is more pronounced for some, while only a very slight supination for others. When athletes roll, fall, or otherwise move into the start from a standing position, there typically is not the subtle movement from the front foot.

I believe it is a mistake to underestimate how good standing start mechanics contribute to overall sprint technique, says @TheYouthTrainer. Share on XIt is my belief that mistakes during stationary standing starts like stepping backward with the back foot to initiate the push-off and/or intentionally preventing the front foot from subtly moving before the push-off interferes with natural mechanics. Although there should not be the subtle movement of the front foot for three-point and four-point starts, I believe there is a positive carryover from good standing start mechanics that support the explosiveness of the push-off into step one from three- and four-point starts.

Stride #2

Ralph Mann considers this stride “the most difficult stride in the entire sprint race.” He also said, “It is the most dangerous since it is this step where, if not done properly, [it] can cause the athlete to stumble forward, rise up too quickly, over stride, or otherwise lose balance. If this occurs, then not only is the power of this single step lost, but it negatively affects the remainder of the Start as well as the transition into maximum sprinting speed.” So conversely, doing a very good job with stride two includes: effective utilization of power, appropriate stride length, preservation of balance, and helping maximize velocity in the first three or four steps, which contributes greatly to the success of the race.

- Ground contact time to begin stride two should be appropriately fast to help build upon the momentum from stride one. Dragging the toes does not allow this, since one of its aims is to slow ground contact.

- A straight back allows the dorsal muscles to work effectively during “foot contact” to begin stride two, thus contributing to the force of the push-off by way of forward pelvic tilt as the body rises (Bosch-Klomp).

- Sufficient joint stability allows velocity to increase as it should, without being slowed by collapsing joints (i.e., knees and ankles).

- Proper use of the limbs, when coming from a four-point stance with starting blocks, includes pulling up the toe (dorsiflexion) to step over the heel of the opposite foot (Valery Borzov) as the knee goes toward the chest.

- Arms are driven down with elbows moving toward the trunk, then immediately back and forth into pumping, running actions (Remi Korchemy), which helps yield maximal mechanical advantage. Arm action for the early strides when coming from a standing start is not as powerful as when compared to three- and four-point starts.

- Sufficient flexibility in the pelvic area is needed so the hips may shift forward sufficiently during touchdown (Ralph Mann).

All of this can help maximize the positive effects of “hinged momentum” (the rotary momentum when the center of gravity travels from the point of ground contact to the final moment of take-off), going from the landing at the end of stride one into the execution of stride two. Controlling the torso is also an important part of maximizing the benefits of hinge momentum and being able to effectively and efficiently move down the track. As a side note, if you can find some of the works of sprint coach Remi Korchemy, he often references the “hinged” pull of the trunk over the foot and aspects related to that, such as “foot torque” and “projecting in front of the heel.”

Stride #3

The hard work has been done, and the athlete then continues with another stride or two of relatively long ground contact to maximize acceleration down the track before ground contact time gets progressively less and less with each stride, and time in the air for each stride increases. Initially accelerating in a sound manner like this helps facilitate an effective rhythm and timing throughout the race, ideally including dorsiflexion of the foot and ankle at the right time.

Jonas Dodoo said, “The natural accelerators have no fear of falling. They can throw their torso forward, they can rotate and they can just throw themselves, they can project themselves. That natural ability is what we’re looking for in acceleration, at least in initial acceleration.” So once again, we’re looking to accentuate a natural quality, and toe dragging does not represent that.

More Practice Methods

As the athletes get better at positioning their body and projecting out at a good angle while being explosive and achieving a good landing position to complete stride one, their balance/stability will likely be challenged, sometimes resulting in some stumbling. Basic positioning during the starting stance has now been mastered, so drills and other learning methods to reinforce good technique for stride two now are most useful. Initially, holding onto something stable can help the athlete lean and get in a position that resembles the start of stride two, and then mimic what the arms and legs should be doing while executing stride two—i.e., dorsiflexion and arm movements. Soon afterward, various types of falling starts can also be used to approximate this position.

I recommend achieving competence from a standing start before putting one or two hands on the ground, says @TheYouthTrainer. Share on XOnce again, 3- to 10-meter sprints with and without competition can be instrumental in developing effectiveness during the first three strides. I believe it is important to encourage the athlete to be aggressive and, as Dodoo said, not be afraid of falling. Being conservative will result in underachieving.

Filming the athletes and reviewing the film with the athletes is also an important part of the process. This includes showing them other athletes to emphasize the techniques being executed at a high level. Sprinting at submax levels of about 80% intensity and above for distances up to 10 meters or so can also allow athletes to be more aware of how they are executing the techniques, since things will be occurring slower. Although, with the action/reaction nature of sprinting, the less intense push into the ground will result in a bit different reaction than would occur if at max intensity.

As I stated before, I recommend achieving competence from a standing start before putting one or two hands on the ground. After the standing start, I believe the next challenge should be starting from the type of three-point stance that is used at football combines for the 40-yard dash. The front foot should be at least be 6 inches from the line, sharing the weight between the feet and the hand on the ground, with the weight centered to the side of the bent front leg.

When the athlete can:

- Bend, hang, and be coiled and loaded to explosively start in a way that—when competing in 3- to 10-meter sprints—projects explosively and effectively, and

- Also achieve a good landing point for stride one that presents a challenge to stability,

then it is time to slow things down and work on second step execution in the same ways as previously described. During three-point and four-point starts, the arms perform a powerful sweeping motion during the first stride and perform more powerful movements during initial acceleration as compared to when coming out of a standing start stance.

The same process is used after moving on to four-point starts without starting blocks and eventually to four-point starts with starting blocks: learning to effectively share the weight and pressure between the hands and feet, centering the weight to the side of the bent front leg, and being loaded and able to project and land effectively before slowing things down to work on second step execution in the same ways as previously described.

How long it takes the athlete to reach a high level of competence at each stage of learning is dependent on the level of instruction and, if given good instructions, the ability of the athlete to successfully apply themselves to the task of creating and effectively building upon the momentum from stride one in a manner that complements the rest of the race.

A Final Word on Toe Dragging

Because the legs recovering low to the ground during the start and initial acceleration is very common among good sprinters, some may be able to pull off dragging the toes without too much difficulty. Especially those who opt for what Ralph Mann calls the “Jump Start.”

Ralph Mann identified two factions with regard to starts: the “Shuffle Start” and the “Jump Start” (both of which he considers to be sound methods). Mann said the jump start can be effective but “With the emphasis on pushing off the blocks as long as possible, the Jump Start places the body into the unwanted Backside Sprint Mechanics position.” In other words, a leg to the rear may naturally be in a position to be dragged without too much trouble. FYI—Mann describes the shuffle start as consisting of short strides, a quick turnover, and more easily developed front-side mechanics from the outset.

If we’re talking about dragging during the second stride, the push-off after the toe drag does utilize the “hinge momentum” that I previously explained, and as I alluded to earlier, I don’t doubt that a longer stride could result. In the context of maximizing velocity, however, utilizing eccentric strength, coordinated natural movements, and a sufficiently fast ground contact makes far more sense. We have to consider how toe dragging affects the rest of the race, and technique in general.

We have to consider how toe dragging affects the rest of the race, and technique in general, says @TheYouthTrainer. Share on XYes, there are extremely successful sprinters who drag the toes, but also great sprinters who don’t. I suggest focusing on what makes sense from a mechanical standpoint, with the objective being to accelerate effectively and efficiently to a max velocity that represents the athlete’s potential.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF