Perhaps no drill is more overlooked for speed development than the drum drill, a timeless exercise used by coaches for decades to help develop frequency. The problem with the drum drill is its popularity never really got off the ground (pun intended), as it required a lot of homework from the coach. In the past, the drill was not convenient to do without a combination of timing and film. Today, the drum drill is now practical thanks to technology and perhaps more valuable than ever, as it fosters more than frequency.

Perhaps no drill is more overlooked for speed development than the drum drill, a timeless exercise used by coaches for decades to help develop frequency, says @spikesonly. Share on XThe drum drill isn’t for everyone, as it does need a lot of skill to perform and a coach who can teach it. In this blog post, I cover everything you need to know to get started and present just enough science to satisfy skeptics. The drum drill is a special exercise—perhaps even more useful than wickets and other similar routines.

What Is the Drum Drill?

The drum drill is exactly what it sounds like: a sprint exercise that requires the runner to cut off their stride slightly to emphasize rapid frequency. In theory, reducing the stride length parameters should slightly increase frequency, and this is where much of the science and mathematics can get tricky. With all of the attention strangely on wickets, the drum has surprisingly been disregarded and ignored. Intuitively, wickets seem more useful, since many athletes look good running over them at first glance, as posture and other qualities show up almost immediately. The drum is not as obvious to the coach, despite having a clear purpose.

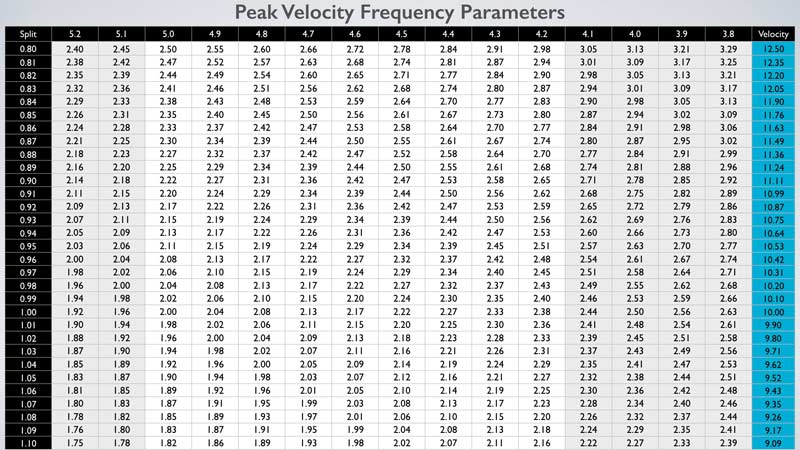

The drum drill is simply a flying sprint with an expectation that the athlete will run at full frequency capacity (five strides a second) at 10 m/s. In theory, reduced stride length with high frequency would then be extended as the athlete becomes more sophisticated and skilled, thus improving general speed qualities for the future. This outcome is something I have failed to see in high-speed film, and I have spent years struggling to replicate the promises of its proponents with my own athletes.

Video 1. Brendan Thompson uses modified drums to throttle frequency up and down for nervous system development. The goal in training is to use frequency drills for long term development, not as a quick fix or similar. You can use markings or keep the track or field naked, depending on your own training philosophy.

The drum drill requires the coach to know the trochanter or leg length of the athlete and be able to cue the athlete in such a way that they don’t artificially score well in the repetition and falsely appear fast due to carrying momentum. An athlete can fake frequency for 10 meters, but they will not be able to carry speed and frequency over 20 meters or more. In fact, I have only seen an athlete hold an unnaturally higher frequency and high velocity for 30 meters once in 20+ years. Keep in mind that I have seen hundreds of athletes on video, many of them medalists and national champions. Legendary coaches such as Gary Wickler and Tony Wells are famous for using the exercise, and Cliff Rovelto has been a proponent as well.

How the Drum Drill Works

The drum drill is an advanced exercise, and young athletes who are growing into their stride should not use it. You can use modified versions with youth athletes as a way to sharpen their nervous system, but when you work with an adult athlete, make sure they can perform quality flying sprints before they start adding complicated versions such as this exercise. Having an athlete who isn’t polished or skilled employ the drum drill may cause them to regress or even learn bad habits.

Having an athlete who isn’t polished or skilled employ the drum drill may cause them to regress or even learn bad habits, says @spikesonly. Share on XThe drum drill isn’t just for advanced athletes; only master coaches should use it. Drills, as I mentioned before, work on their own and are not always perfect. Some drills have a knack for doing much of the heavy lifting with form or technique development, but coaches must be vigilant to ensure drill’s intentions are instilled in the session they are part of. I believe that extensive experience with floating sprints can make the leap to the drum drill far easier, but the nuances of acutely modifying stride frequency and contact times make it hard, especially as athletes develop their speed near their genetic ceilings.

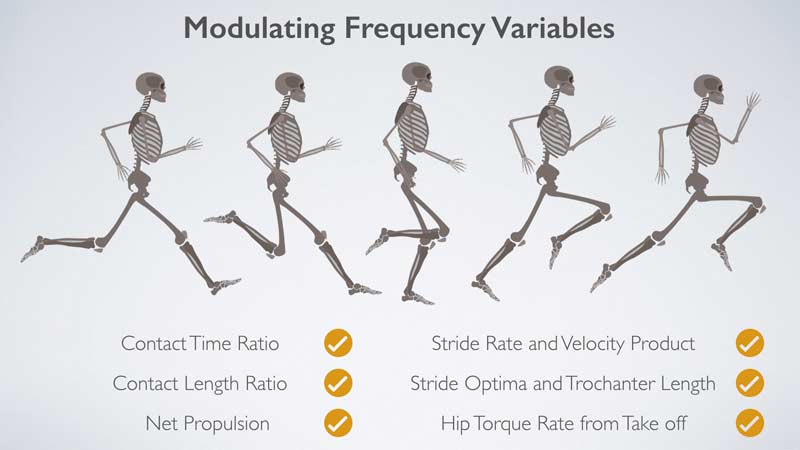

When the athlete performs the drill, the expectation is that they cut—they use a stride movement strategy that doesn’t disrupt the sacred contact time, stride length, and contact length balance. I have mentioned the importance of knowing contact length and being able to measure ground contact time. Frequency often improves when contact times decrease, while stride length rarely increases at the same rate.

Each athlete will have different development patterns. Some athletes are frequency heavy when they are young and may grow their length as they become more powerful, but usually both stride frequency and stride length will mature at the same rate until athletes hit a genetic ceiling. Then, based on my observations, they will need to reduce ground contact time in order to continue to improve. Thus, many coaches gravitate to the drum drill because they know that it takes a long time to improve contact times and rapid turnover.

Why the Drum Drill Can Fail

Frankly, if you don’t tell others what can go wrong with a drill or exercise, you do them a disservice. The drum drill can be magical, but as with any tool, it does come with its own unique challenges. First, many athletes find the drum to be difficult to perform since it only works if you can keep velocity nearly identical to your top speed. Some coaches feel that you should run and hit five steps per second, and this may be very foreign to a long strider who is tall or has low frequency. Such an abrupt jump is very awkward and unnatural; thus, I prefer a slowly saturated frequency if possible.

Athletes can find the drum drill difficult to perform since it only works if you can keep velocity nearly identical to your top speed, says @spikesonly. Share on XAn easy way to determine frequency is to use the ground contact times and air times of a flying sprint and divide the sum into 1,000. I don’t use a chronometer and video anymore, as the process is time-consuming, but you can do so if you are pressed for a budget and don’t have MuscleLab equipment.

Many athletes try to run faster by either putting more force into the ground or shutting off power, thus extending ground contact times or tightening up. The irony is that trying to improve speed or even a component of speed may cause the reverse to happen, where an athlete either slows down or decreases their frequency slightly. Higher-frequency athletes tend to struggle with enhancing something that is already there, and athletes who have low frequency can become slower in efforts to increase velocity.

Athletes with long strides that are artificially proportional to their leg length tend to need frequency drills to improve their strike points (Hunter 2020), and this will solve excessive air times that come with long striders. Those who are “reachers” tend to have a problem decelerating knee extension and/or fail to push down actively during the backswing. Frequency drills such as the drum drill can clean up that small error, and this often results in fewer hamstring injuries. The knee lift, specifically the hip flexion angle at takeoff or later, should not be dramatically disrupted, or the athlete will tamper with the braking and propulsion balance of their foot strike.

March to the Beat of Your Own Drum

The drum drill is just one option in stride frequency development. Most of the time, the drum drill can be seen as just a rhythm drill that allows an athlete to relax and experiment with the right range of motion and bounce. A solid background in floating drills and developing reactivity should help athletes mold their stride into a balanced motion that maximizes their speed.

I have used frequency drills for years and now understand the nature of stride development mainly from shaping the stride parameters we all have known about for a long time. The drum drill is a special exercise that can make a great change in athletes who are receptive to improving and with a coach who is worth their salt in instruction. The drum drill is just one option for improving an athlete, and it’s more than fine to use any method you see fit that helps improve stride frequency.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF