The MuscleLab contact grid is a novel measuring device that virtually turns a training surface—specifically a track or sports flooring—into a measurement zone. The area, ranging from a few yards to about 40 yards, detects foot contact durations. With a contact grid, a coach can estimate jump heights and various stride parameters such as stance time, flight time, and more. This anthology covers the best articles on using the contact grid and includes additional resources that will expand your use of the technology further. The contact grid is an exceptional tool, and you should know that it integrates with other MuscleLab products, including the Dynaspeed and Laser, using a synchronization unit.

Getting Started with the MuscleLab Contact Grid

In this article, Carl Valle covers the essential needs for setting up and operating a MuscleLab contact grid, including software and hardware installation. As one of the technology’s biggest proponents, Coach Valle shares fundamental recommendations on best practices, including testing and training with the system. Regardless of whether you are an advanced user or simply just interested in how the product works, this is a good primer for everyone.

In this article, Carl Valle covers the essential needs for setting up and operating a MuscleLab contact grid, including software and hardware installation. As one of the technology’s biggest proponents, Coach Valle shares fundamental recommendations on best practices, including testing and training with the system. Regardless of whether you are an advanced user or simply just interested in how the product works, this is a good primer for everyone.

Buyer’s Guide to Contact Mats and Contact Grids

The contact mat and grid market is wide, ranging from simple mats all the way to sophisticated runways. This buyer’s guide is an exhaustive list of providers of hardware and includes key differences between all of the systems available. Before investing a single dollar into testing equipment, it’s recommended that your review the guide to make the right choice for your athletes.

The contact mat and grid market is wide, ranging from simple mats all the way to sophisticated runways. This buyer’s guide is an exhaustive list of providers of hardware and includes key differences between all of the systems available. Before investing a single dollar into testing equipment, it’s recommended that your review the guide to make the right choice for your athletes.

The Top 8 Ways Coaches Can Use MuscleLab

Another Carl Valle article, this piece really shows the range of options that MuscleLab has to offer. In addition to the other products mentioned in the article, Coach Valle hints at the power of synchronizing multiple measurement tools for a deeper dive into the activity that professionals can measure. If you are looking to invest in a jump and speed solution but are cognizant about expanding your options in the future, this article is right for you.

Another Carl Valle article, this piece really shows the range of options that MuscleLab has to offer. In addition to the other products mentioned in the article, Coach Valle hints at the power of synchronizing multiple measurement tools for a deeper dive into the activity that professionals can measure. If you are looking to invest in a jump and speed solution but are cognizant about expanding your options in the future, this article is right for you.

Why High School Coaches Should Invest in Performance Tech

Ryan Denton is a high school coach who shares his story of using the contact grid before expanding further with additional sensors for speed testing. Included in the article are how he was able to raise funds and the necessary time investment spent to learn about other measurements outside typical testing. If you are a high school coach and want to take long term athletic development to the next level, this is recommended reading.

Ryan Denton is a high school coach who shares his story of using the contact grid before expanding further with additional sensors for speed testing. Included in the article are how he was able to raise funds and the necessary time investment spent to learn about other measurements outside typical testing. If you are a high school coach and want to take long term athletic development to the next level, this is recommended reading.

How to Set Up Hurdles for Better Plyometric Training

One of the most popular ways to use the contact grid is to help guide spacings and heights when jumping over hurdles. This article includes videos on what is considered a properly executed jump and what to do in order to measure ground contact times and flight times properly. Regardless if you are already using the contact grid now or curious about using it later for jump training, this article is one of the most in-depth resources on hurdle jumps available.

One of the most popular ways to use the contact grid is to help guide spacings and heights when jumping over hurdles. This article includes videos on what is considered a properly executed jump and what to do in order to measure ground contact times and flight times properly. Regardless if you are already using the contact grid now or curious about using it later for jump training, this article is one of the most in-depth resources on hurdle jumps available.

15 Uses of the MuscleLab Contact Grid

Rob Assise, a jumps coach in track and field, shares a whopping 15 ways to use the contact grid in this article. Not only does Coach Assise include the different exercises but also the details of creating the measurement on the MuscleLab software. If you are on the fence about whether you should invest into the MuscleLab contact grid, this article will likely convince you to move forward.

Rob Assise, a jumps coach in track and field, shares a whopping 15 ways to use the contact grid in this article. Not only does Coach Assise include the different exercises but also the details of creating the measurement on the MuscleLab software. If you are on the fence about whether you should invest into the MuscleLab contact grid, this article will likely convince you to move forward.

The Scandinavian Rebound Jump Test: Why Every Athlete Should Use It

The Reactive Strength Index, or RSI for short, is one of the most favored jump tests in sports performance. While it’s easy to perform, this article shows a modification of the test that can improve both its validity and accuracy while making it easier to administer. It doesn’t matter if you are an elite coach needing a scientific solution for measuring elasticity or a new coach wanting to get started, this article is for you.

The Reactive Strength Index, or RSI for short, is one of the most favored jump tests in sports performance. While it’s easy to perform, this article shows a modification of the test that can improve both its validity and accuracy while making it easier to administer. It doesn’t matter if you are an elite coach needing a scientific solution for measuring elasticity or a new coach wanting to get started, this article is for you.

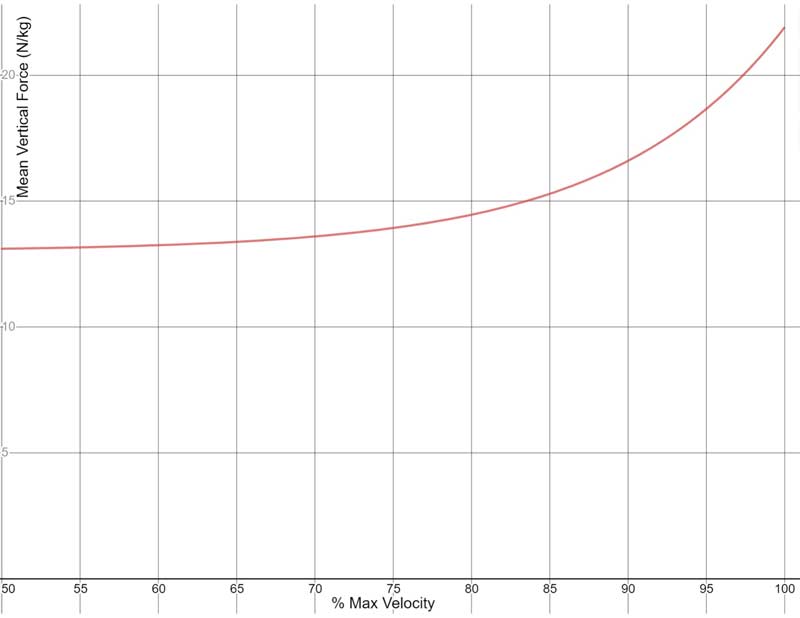

Athlete Leg Stiffness

Mike Young, a leading expert in performance, covers the necessary ways to train stiffness in his breakthrough video course. Dr. Young, who is a new user to MuscleLab, outlines a scientific and practical way to train plyometrics with the contact grid. If you are serious about training and want to learn, or if you are a user of the contact grid and want better direction in training, this video course is appropriate.

Mike Young, a leading expert in performance, covers the necessary ways to train stiffness in his breakthrough video course. Dr. Young, who is a new user to MuscleLab, outlines a scientific and practical way to train plyometrics with the contact grid. If you are serious about training and want to learn, or if you are a user of the contact grid and want better direction in training, this video course is appropriate.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF