The last day of school is a very special day for non-coaching teachers and students who are not involved in athletics. It signals a long rest. A time for both faculty and students to have 8-10 weeks of relaxation. At the very least, they have that amount of time to enjoy not having to think about being at school.

Coaches and student-athletes also look forward to that special day. As we know, however, it’s not because of anticipated long stretches of relaxation. Instead, it signals the beginning of summer practices, camps, tournaments, and strength and conditioning workouts. This is an enjoyable time for most. It’s also a busy time for all.

The Most Fertile Training Period

No coach spends more time on campus during the summer than the strength and conditioning coach. Most sports have a two- or maybe three-hour block during the day 3-4 times a week when they work with athletes. If you work with multiple sports, your day could last six, eight, or even 12 hours. At York Comprehensive High School, my day runs from 7:30 a.m. to 1:15 p.m., which is close to what a full work day runs during the school year, in terms of total hours. It may be more because there is no break during that time. We just roll one group after the other.

While we do look forward to and enjoy this time of year, it doesn’t come without its unique challenges. For me, it’s a great time. While we don’t have the time off other educators get, we get the opportunity to do what we love year-round. The time, while enjoyable and productive, presents us with obstacles that make us think outside the box.

This article will discuss some of the situations I have experienced and how we have worked around them the best we could. Things we don’t have to deal with during the school year are now issues. Sports teams from all three seasons will now have practices and strength and conditioning needs. Compounding this is the need to share multisport athletes.

Most sport coaches will talk a good game about “sharing,” but won’t always demonstrate actions that coincide with that. While we may not coach a sport, that situation will inevitably drag us into a Pandora’s Box. Add in the next layer to that issue: middle school athletes. Some states bar joint workouts with middle school and high school students. My state allows it.

Getting a talented, rising seventh grade athlete who has a training age of zero and plays three sports can present a multitude of problems during the summer “free for all.” If you also “block” your athletes, as I and many others do, you may end up with six or eight different variations of a session going on, all at once. On the other end of the seventh-grade athlete issue is the training age zero rising senior. How do we encourage that initial foray into high school athletics when the athlete’s teammates are years ahead on the training age spectrum?

In the summer, athletes often miss days or even weeks of training and practice. How do we account for that within the training calendar? These issues highlight the obstacles strength coaches face once summer “vacation” begins.

Scheduling Sessions – A Solution to the Nightmare

Scheduling sessions is the first hurdle we must cross in the journey to creating and implementing a successful summer workout plan. The main factor that needs to be navigated before any scheduling decisions can be made is whether to schedule as “sport” groups, male and female athletes, or some combination of the two. I’ve done a little bit of all three over the years. One thing that always stays consistent is putting football on its own. The pure numbers make it difficult to share the room.

My process begins with nailing down the exact times that ninth grade, JV, and varsity football will need me. That’s the easy part. I can’t speak for every situation, obviously, but in my experience, football is the only group that the vast majority of the athletes and coaches show up for year-round. This group gets priority scheduling because of that year-round effort, right or wrong.

After football gets slotted in, the next decision is male and female groups or sports teams. This is where the aforementioned “Pandora’s Box” situation comes into play. If we select sports teams, that presents us with a couple problems.

Scheduling summer S&C sessions gets tricky when dealing with the various sports coaches who expect the multisport athletes to attend their training sessions, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XOne is having enough time to get all the teams in individually. The other is how to deal with the many multisport athletes we have and navigate the sometimes-fragile relationship between various sports coaches who expect those athletes to attend their session. Often, the multisport athlete is one of the better players for both teams, and sometimes a leader on both or even three teams. I have done it both ways in different situations. However, if you have more than 2-3 teams of female or male non-football athletes, it gets tricky fast.

At YCHS, we have decided to go away from individual team sessions, even as far as our classes go. We are in the process of switching from sport classes to male and female. Neither way is totally ideal. This summer, for example, our female athletes are with me from 8-9:15 a.m. and our male non-football group from noon to 1:15 p.m. In the past, we have gone later, from 11-12:15, because most of our female teams held summer practice from 9-11 am. Our 8 a.m. slot had been male, non-football.

This year, we had one female team move their practice time to 6-8 a.m. So we had one team early and the rest at 9:15 a.m. My solution was to move our female weight room time to 8 a.m. That puts the single sport athlete on campus four days a week for about three hours. For our multisport female athletes, that may cause them to be on campus from 6-11:30 those four days. That will be an issue for sleep and recovery, as it would be for any teenager.

There is no perfect solution. As strength and conditioning coaches, all we can do is find the best scenario possible and monitor the athlete the best we can. If we see any issue, we can adjust the workload on our end. In our situation, I find it best not to encourage “team” training. Our program is unified, and I see no reason to get involved in the division of sports teams.

Middle School Athletes – Consider Biological and Training Ages

When I coached in North Carolina, the issue of training the middle school athlete was simplified by state-mandated rules. It was simply stated that no student enrolled in the middle school or below for the following school year was permitted to take part in any practice or training session involving high school students. I hosted a summer camp in the evening and ran a speed and quickness program through the recreation department.

In South Carolina, it’s not that simple. Middle school athletes can and often do attend our after-school and summer programs. In fact, eighth graders can play at the junior varsity level. That throws a pretty big wrench into the situation.

I have had both seventh and eighth grade females show up to summer sessions, along with rising freshmen and 10th-12th grade athletes. It gets complicated fast. This is where I lean on our sport coaches for support. Without their attendance and help, I would be forced to turn those students away or add a session that would either be hours before or hours after their practice sessions.

This situation requires us to be masters of multitasking and not get flustered easily. I work directly with this group with the help of one other coach. I still run our clock, coach on the run, etc., but I have to count on my sport coaches to be strong assistants and help with the coaching and supervision of the older, more experienced athletes in the group.

While training our young group to be prepared for the high school level is extremely important, I make sure to remember that my priority is our current athletes, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XMaking sure the coaches you know will be there are educated on how you do things is imperative. One thing I make sure to remember is that my priority is our current athletes. While training our young group to be prepared for the high school level is extremely important (which is why I do it myself), there are times when my focus must be on our older group. I explain that to our coaches and athletes.

At that time, it is important to have the sport coach who helps you with the middle school group be well-versed enough in your Block “0” protocols to take over the group when needed. As is a common theme in many of my articles, we must take the time to properly train and educate sports coaches in the nuances of what we do. They can and will be invaluable to you if they are prepared to jump in when needed with more than the most basic coaching.

Blocked Athletes – A Simple Solution to a Complex Problem

I have always believed that the best-case scenario for grouping athletes is by training age or blocking. Imagine if we had the ability to have all athletes within the same block within a session? Even two blocks combined, as long as they are concurrent, would be extremely helpful. I have never been in a situation where that was feasible. The closest I get is having the varsity football team in the same class during the school year.

In the summer, it can get pretty far in the opposite direction. In addition to the middle school athletes I spoke of, I have all levels of training age blocks from one (new lifter) through four (elite). To make the situation even more complicated, every summer I get the inevitable athlete or two who are juniors or seniors but have never played a sport or taken part in our strength program. Essentially, they are block ½, or at best 1 ½, athletes. Most have a basic knowledge of working out, but very little in the way of technique or how to perform what our higher block athletes in those grades can perform.

I have always believed that the best-case scenario for grouping athletes is by training age or blocking, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XThe first part of this potentially difficult equation is to make sure we have “slow cooked” our athletes. If we have progressed each of our older athletes as we should have, we have a leg up. It’s vital that you have a process to teach slowly and with great attention to detail. That makes things much easier when you get to a situation with many levels training at once. Our program motto is “Master the Ordinary.” If both our higher block athletes and sport coaches are educated and willing to make sure that the ordinary, basic things in our program are done right, it allows me to spend extra time teaching those things to our lower block athletes.

The second aspect is program organization. CoachMePlus is the tool we use for this. I have also organized the program in the past with Excel sheets, but it’s much more time-consuming to prepare. Using CoachMePlus, we create micro groups that are put together by block. Therefore, we may have five different blocks training, using five different variations of the workout, but each has their own assigned areas. This allows us to monitor and coach at the group level.

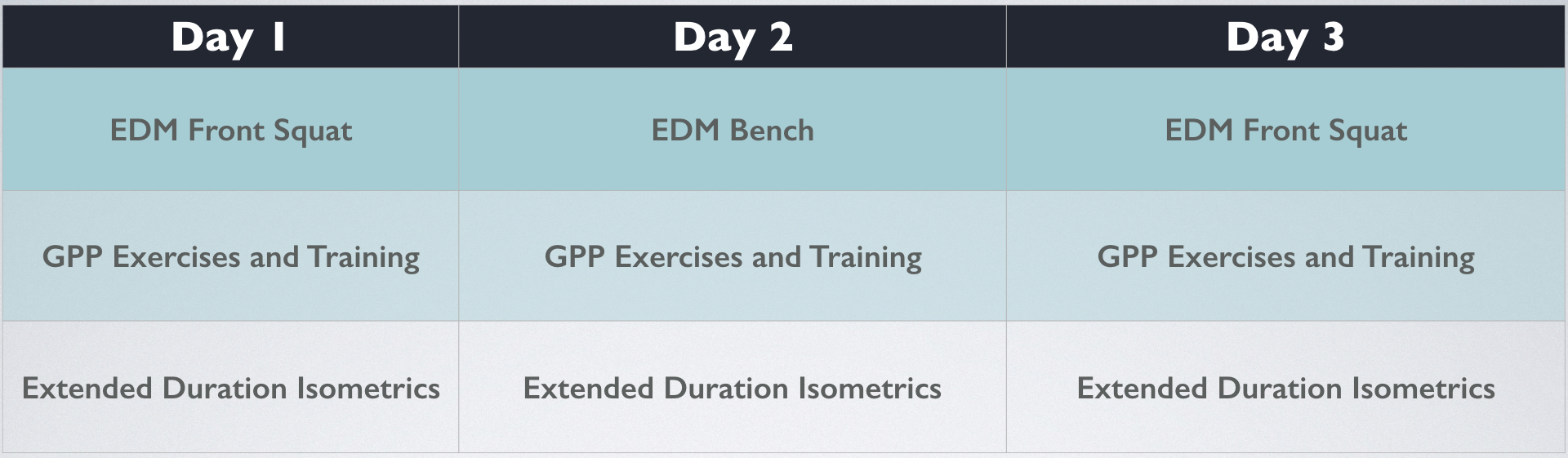

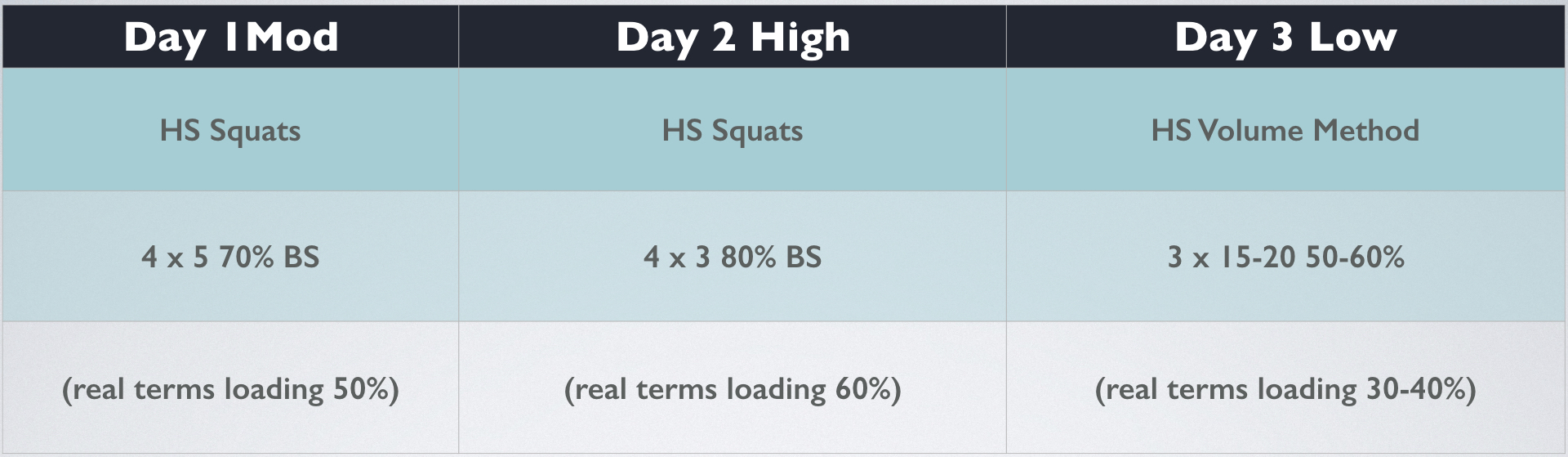

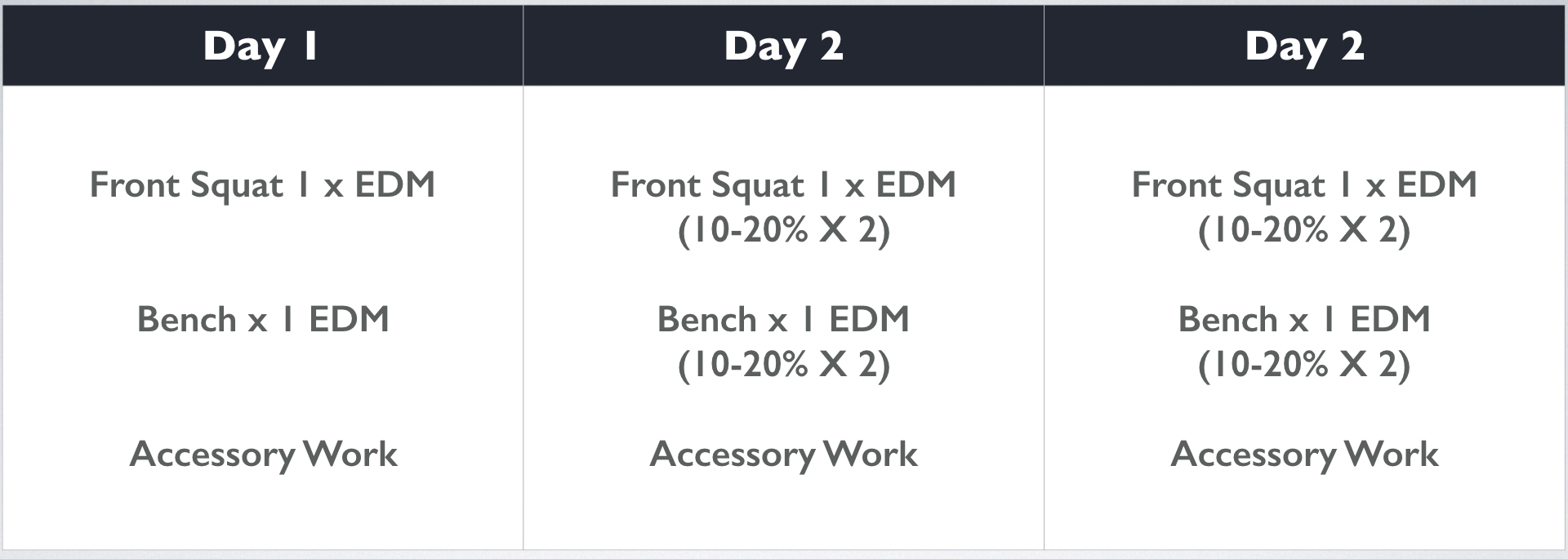

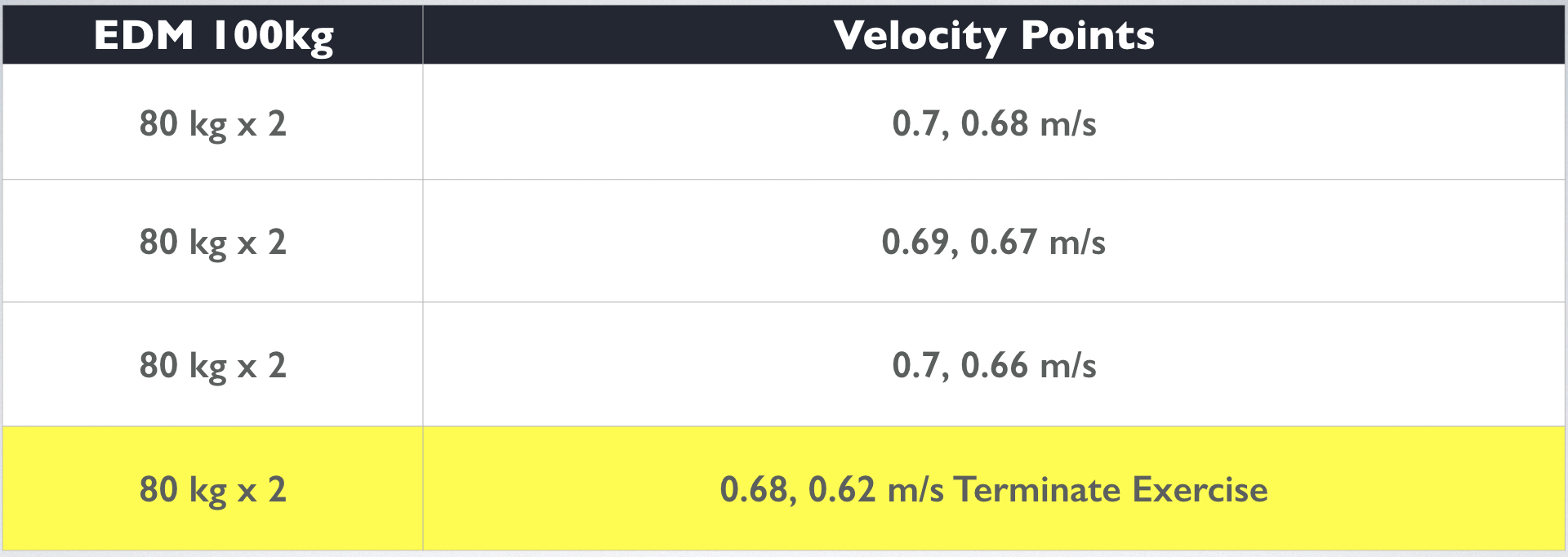

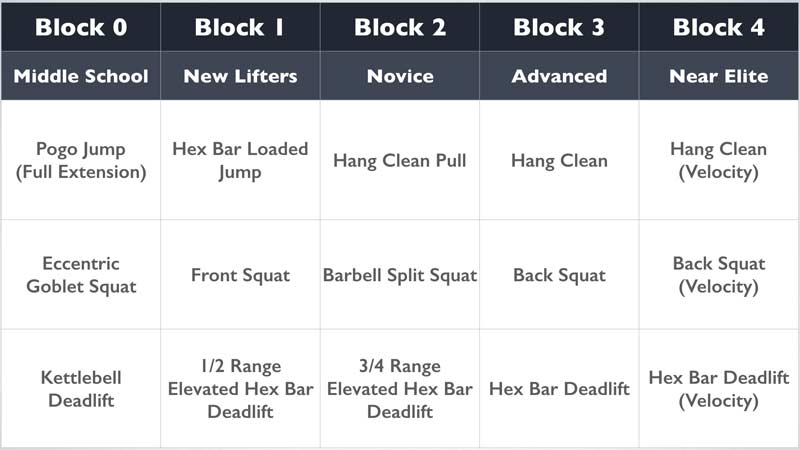

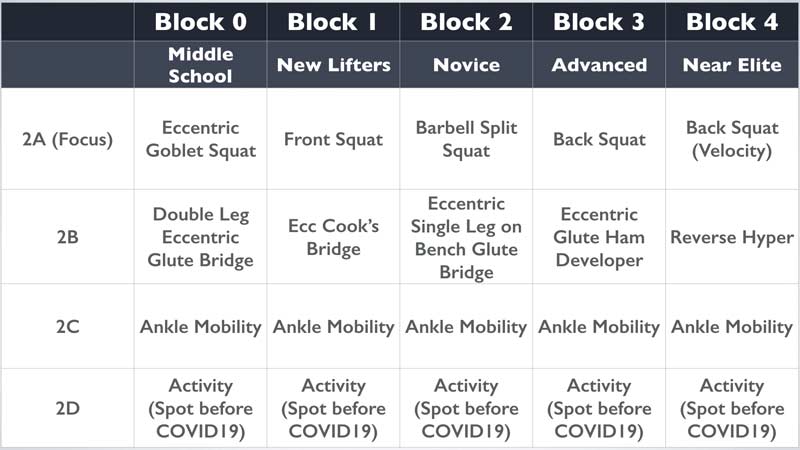

Another important factor in this is the use of a unified program. Below is a chart that lists several of our main movements and how we differentiate them by block. By using a unified program within our modified tier system, we can have each block doing a training-age-appropriate movement, but within the same movement family as all the other blocks.

So, for example, on a squat day in our max strength Tier 2, everyone in the room will know they will do a variation of the squat (within our progression), as well as whatever hamstring/glute movement and mobility/flexibility movement are in each set in the tier for that day. While we still have a lot going on, I and the other coaches all know what basic movement each athlete is doing. It allows mass teaching and coaching to run as smoothly as possible.

Below is an actual example taken from one of our recent workouts.

We use this basic model for all our programming from Block 0 to Block 4. Our athletes and coaches will have an idea about what movements they will be doing each session from day 1 to graduation. We also do not change what we do in the weight room based on a sport-specific thought process. Our goals are the same for all athletes and we use a consistent and unified program to develop and achieve those goals.

This also helps me during the busy summer months by ensuring that all our coaches and athletes are on the same page. My softball coach can assist me with our basketball, volleyball, or even football athletes, if the need arises.

Summer Vacation – The Curveball We Know Is Coming

The final summer-specific issue I will discuss is something all coaches have to contend with. The last day of school is likely the final time any coach will have all their sport’s athletes present at the same session until mandatory practices begin in August. It’s something that can frustrate coaches, but we can’t do much about it.

While we all have athletes who plan their entire schedule around the sport’s schedule, most do not. Vacations, camps, and distractions can lead to the loss of training days. My advice to all our athletes is “do your best to be here.” If it’s important to them or their parents, they will figure it out. As we all know, it’s not as important to most as it is to us. We have to have a plan. Mine is not complicated.

Again, I go back to having an online-based program as an advantage. For us, it’s CoachMePlus. The athletes get an email every day with a link to the workout. In all likelihood, the sport coach will not give them credit for “distance training,” but at least they have the opportunity.

I have no illusions that many of our athletes take advantage of this, but the opportunity is there. If they just do the main scheduled movements, they will not fall far behind. When I was Excel-based, I would supply them with a sheet if they asked (they never actually did, though).

Overall, I don’t let myself get too stressed about the vacation situation. Teenagers are resilient. We’ll catch them up as needed. The bulk of our training is done outside of summer anyway.

I don’t let myself get too stressed about the vacation situation. Teenagers are resilient. We’ll catch them up as needed, explains @YorkStrength17. Share on XIn South Carolina, we basically have six weeks between graduation and the start of fall practice. This includes two “dead weeks.” I won’t worry about an athlete until they have missed a couple weeks in a row. I have no magic solution for this age-old situation. Like everyone else, we just try to offer opportunities and help our athletes make great decisions.

Get the Most out of Your Summer Months

I hope this piece has given you a small insight into how we do things at YCHS. I am grateful for the opportunity to assist you and thankful that you took the time to read this article. I hope you can take any part of this that interested you and use it to your advantage. Feel free to contact me to expand on this or any other topic I can be of assistance with. I wish you a happy and productive summer.

Editor’s Note: Block Zero and other tier concepts from Joe Kenn have been referenced in past articles and is considered mainstream. See How to Introduce Youth Athletes to Strength Training for an explanation of how this works.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF